Overview of the Theory

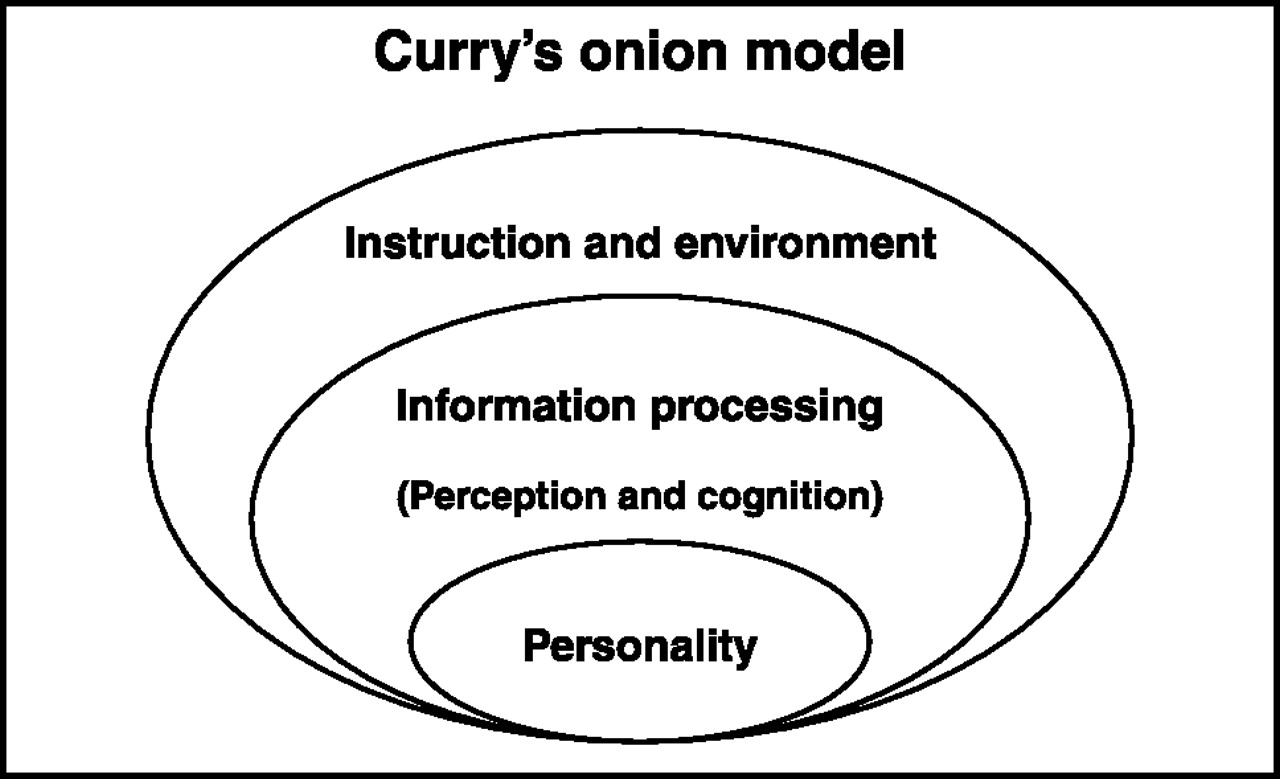

In Curry’s onion model, the core layer is the cognitive personality style. It describes how an individual assimilates and adapts information (Cools et al., 2009). It delineates a person’s cognitive processes of “perception, thinking, memory, and learning” (Cools et al., 2009, p. 176). It is the most stable stratum of the model that is related to a more fixed personality. It entails the basic approach a learner utilizes to think or assimilate new information. For instance, individuals with a convergent thinking approach focus on the answer, while those with a divergent orientation explore multiple options (Cools et al., 2009).

Learning Style Conceptualization

The cognitive personality style (CPS) is conceptualized as the fixed personality dimensions – attitudes, preferences, and habits – regulating a student’s information adaptation behavior (Cools et al., 2009). It entails the unique, consistent individual preferences for particular approaches to obtaining, processing, and assimilating information. It interacts with the external environment through the two outer levels: information processing style and instructional preference style (Cools et al., 2009). CPS focuses on cognitive and perceptual differences that account for variations in learning approaches between students.

Research Related to the Theory

Peterson et al. (2009) provide a conceptual definition of cognitive personality style based on an e-survey of researchers. They define it as the individual differences inextricably connected to one’s cognitive system (Peterson et al., 2009). Research on cognitive style considers it a stable concept that can be generalized and does not vary across learning contexts (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008). Cools et al. (2009) found that cognitive styles – understanding, planning, or creating – correlates with individual attitudes, which are shaped by experience and external influences. A cognitive style profile of a learner may be unchangeable or prone to experiential influences. The personality aspect of learning determines the preferred informational processing and instructional approaches.

Studies examining cognitive personality style in an educational context show that personal (student) preferences in communication influence academic attainment (Li et al., 2011). The two categories of cognitive styles seen in student nurses differ on the thinking-feeling dimension. Further, assessment feedback preferences differ between male and female students (Evans & Warring, 2011). Thus, student-educator congruence on preferred communication and assessment feedback can lead to improved academic achievement.

Learning Style Instruments

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) contains 93 forced-choice items that measure individual preferences and group them into four categories, namely, “extrovert/introvert, intuitive/sensing, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving” (Li et al., 2011, p. 22). It is a self-administered questionnaire. In contrast, the Embedded Figures Test is a group-administered instrument that assesses field independence or dependence of learners (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008). A field-independent person is able to discriminate content from a context, i.e., he or she has an internal locus of orientation (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008). The other instrument is the Matching Familiar Figures Test that measures the reflectivity-impulsivity trait in learners. Reflection implies the disposition to consider multiple solutions to issues, while impulsivity entails spontaneity (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008).

Measurement Issues

The cognitive style measurement issues relate to construct validity and reliability of the instruments. The test may not evaluate the intended theoretical constructs. A factor analysis reveals that the items or questions have no strong relationships with the dimension they are measuring due to cultural or gender biases (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008). The poor construct validity affects the robustness of the instruments in measuring the intended concepts. Another issue relates to the changeability of cognitive style over time, reducing the reliability of the measures. Further, overlaps between the clusters means that the characteristics are not exclusive, but rather shared across groups. Thus, it is not possible to obtain pure cognitive style profiles or maintain consistent measurements over time.

Samples of Instruments

EFT has a paper-based and an online version that helps break the geographical barrier since it can be administered to respondents in multiple locations. It measures the perceptual ability that determines one’s cognitive learning style. The original MFFT version comprised 14 items (two practical and 12 experimental) (Evans & Waring, 2011). It entails matching variants with a standard. The MBTI is a self-administered inventory. Related instruments, such as the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, produce clusters comparable to those of MBTI.

Limitations

The EFT measure of independence is similar to instruments that assess intellectual ability, such as IQ tests (Peterson et al., 2009). Therefore, it focuses more on intelligence than on learning style. In the MFFT, there is an overlap of constructs, which means that the definitions of the concepts are not clear-cut. Reflective individuals may not be exclusively field-independent. Similarly, persons with an impulsive orientation (field-dependent) may have an internal locus of control that is associated with field-independence. The MBTI does not show the expected bimodal distribution, an indication of its low reliability and validity.

Application of the Learning Theory

The main practice applications of the cognitive personality style are in the areas of nursing education and specialty selection by student nurses. Matching the learner’s cognitive style profile (didactical and communicative preferences) is associated with improved academic outcomes (Li et al., 2011). Similarly, using a preferred delivery approach – lectures or online courses – can yield better results. Further, students can be mentored to pursue specific nursing specialties or careers that match their cognitive personality style. Thus, the knowledge of CPS can help nurses pursue fulfilling careers.

Barriers to the Use of the Learning Theory

The model shows limited consistency over time. A test-retest done within a short period shows a longitudinal change in cognitive personality style, implying that external factors influence the CPS (Evans & Waring, 2011). The poor reliability and validity of this model constitute a barrier to its use. In addition, there is an ambiguity over whether the cognitive style is a state (experiential) or trait (stable characteristic). The model is also prone to gender and cultural biases, especially against non-western cultures that do not conform to the MBI categories. Cognitive styles are not static; they vary between generations. Thus, there is no ideal model for all generational groups or cultures.

Barriers to the Use of the Instruments

Measurement inconsistencies inherent in some instruments imply that a person may be classified in a different cluster after a test-retest. Further, the scoring of the effects of CPS on performance is a challenge; they vary depending on task and context. Another barrier relates to the limited use of the instruments after they were proposed. Thus, the empirical evidence for their use to measure cognitive personality styles is lacking.

Recommendations

When assessing cognitive personality styles, it is recommended that a prior analysis of available research evidence for the use of the model be done. It should also include reliability and validity tests of the instruments and measures to be used. Use an appropriate instrument for work based on the objectives of the research. Further, appropriate operationalization of the cognitive personality styles can be achieved by understanding student idiosyncrasies, generational differences, cultural nuances, etc.

Student nurses have diverse and unique cognitive learning style profiles or traits. Thus, a one-size-fits-all instructional approach may not be effective. It is recommended nurse educators use a variety of teaching methods that appeal to different cognitive styles, e.g., lectures and online courses. The aim is to engage the whole spectrum of CPS profiles in class in a meaningful way. In addition, knowledge of the cognitive styles, and generational, cultural, and gender differences can help design inclusive didactic methods. A student-centered model can help all learners adapt to the nursing curriculum and select a nursing specialty that matches individual CPS profile for optimal academic and professional outcomes.

Implications for Nursing Education

The cognitive personality style has implications for nursing education and specialty mentorship. The nursing faculty should change their teaching methods to conform to student CPS continuums in class. Further, the educators should use instructional approaches that are accommodative and student-centered to meet the learning objectives of a course and improve the overall academic performance. The educational contexts should incorporate activities or tasks that engage student cognitive personality styles and communicative and didactic preferences. Mentorship programs at the undergraduate level should be based on the predominant CPS traits.

References

Cools, E., Van den Broeck, H., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2009). Cognitive styles and person-environment fit: Investigating the consequences of cognitive (mis)fit.European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(2), 167-198.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2008). Personality, intelligence and approaches to learning as predictors of academic performance.Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1596-1603.

Evans, C., & Waring, M. (2011). Student teacher assessment feedback preferences: The influence of cognitive styles and gender.Learning and Individual Differences, 21(3), 271-280.

Li, Y., Chen, H., Yang, B., & Liu, C. (2011). An exploratory study of the relationship between age and learning styles among students in different nursing programs in Taiwan. Nurse Education Today, 31, 18–23. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.03.014

Peterson, E. R., Rayner, S. G., & Armstrong, S. J. (2009). Researching the psychology of cognitive styles and learning style: Is there really a future? Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 518-523. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2009.06.003