Introduction

The relations of human beings within the society are conditioned by complex phenomena that are mainly focused on the issues of benefit and personal income that every person tries to increase. If the question of income comes into play, the usual area for consideration of this question is the area of wages, their inequality and the necessity to compensate for the possible differences observed (Bhaskar et., 2002). People have different jobs, various working conditions, and wide ranges of work and retirement benefits. However, people hold the belief that all people are created equal and the situations when some people earn more than others cause conflicts. To avoid the latter, employers should focus on policies allowing more or less equal wage differentials compensations. Thus, the assessment of the empirical study findings of wade differentials is the focus of this paper.

Wage Differentials

The major idea of wage differentials lies in the fact that formerly all workers were perceived as equal and their wages were equal as well. However, later the concept of wage differential compensation was introduced to consider the inequalities that are observed in working environments and capital investments that people make to acquire new skills and increase the utility of their work (Blau and Kahn, 2006). Considering also the relation of risk the job presents and the wage levels, the following formulae are used to measure utility and marginal utility respectively. Adam Smith was the first scholar to notice these differences that were later formulated in the following functions:

U = U (w, ρ)

MUw =ΔU/ΔWρ or MU ρ =ΔU/ΔρW

Log Wi/Pi = a1 + a2Ii +a3Ii2 + a4Si +a5Xi + a6Pi + εi

These formulae illustrate the fact that wages increase proportionately to the risk of the job and to the readiness of an employee to take those risks and work in a less comfortable working environment.

Empirical Studies

Basic Data

Further on, empirical studies were carried out in Sweden between 1968 and 1974, and their results proved that people exposed to less favorable working conditions expect and actually get higher wages and 3 to 4% premiums, while those dealing with mental work can expect 5% premiums.

Studies carried out by Brown (1980), Smith (1979), etc. demonstrate the levels of readiness of workers in USA and UK to earn lower wages but to be exposed to less danger and lethal threats at work. Scholars tried to see how much the workers are ready to pay for safety in the workplace, and the results of their work can be summarized in the following table:

The above table demonstrates that scholars have managed to find out the direct relation between the wish of people to work in safety and their readiness to agree on wage reduction to ensure the former. Moreover, the above results can be explained by hedonistic theory and human capital theory of wages.

Hedonistic Theory of Wages

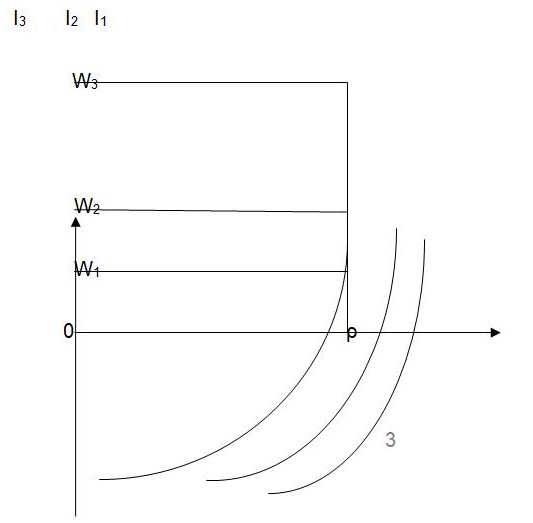

Thus, the hedonistic theory of wages suggests the direct relation of the heterogeneity of workers and the potential of getting injured at the workplace as the main factor facilitating wage differentials (Leuven, 2005). It is up to employers in this context whether to choose the provision of safe environment and lower wages, or invest the money potentially directed at safety systems updating into the wage increases and compensate the employees for their work in risky environments. The following graph illustrates the progression of wage increase and risk growth in the workplace (Fig. 1): I3 I2 I1

Drawing from this graph, hedonistic theory of wages concludes that the workers that work in a riskier environment earn more. Therefore, each firm employs workers who are either inclined or not to take risks for higher wages.

Human Capital Theory (HTC)

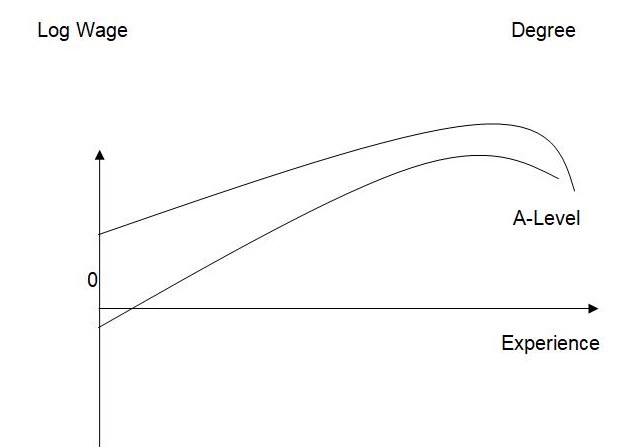

Moreover, the human capital theory considers another side of the issue, i. e. the investment people make into their education and further skills acquisition. The theory claims that the more investment is made, the higher wages an individual can have (Fig. 2):

The chart above shows that people who invest more in their education and skills acquisition earn more and the progression of their income growth reaches its peak closer to the end of the life cycle (Hall, 2005). Moreover, the formula of the log wage shows how the growing wages are constructed:

log w = α + β1s + β2t + β3t2

(+) (+) (-)

Moreover, the so-called Present Value (PV) of the education or job acquisition is also considered by people, according to the HTC, in their choices of either continuing education or taking up job at once after school:

Thus, empirical studies prove and the above theories ground the fact that people are inclined to assess the wage compensations for their work based on risk factors, their wish to either avoid or take those risks, and the investments they have made in the development of their educational basis and professional skills.

Conclusions

To conclude, people have different jobs, various working conditions, and wide ranges of work and retirement benefits. However, people hold the belief that all people are created equal and the situations when some people earn more than others cause conflicts. To avoid the latter, employers should focus on policies allowing more or less equal wage differentials compensations. The empirical studies considered suggest that there is a direct connection between risk levels, comfort of working conditions and capital investment to the wages that a person earns, and hedonistic theory of wages and the human capital theory prove these suggestions.

References

Bhaskar, V., Manning, A. and To, T. (2002), “Oligopsony and monopolistic competition in labor markets”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 155-74.

Blau, F. D. and Kahn, L. M. (2006), “Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980-2000”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2180.

Brown, C. (1980), “Equalizing differences in the labor market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94, 113-34.

Hall, R. E. (2005), “Job loss, job finding, and unemployment in the US economy over the past 50 years”, NBER Working Paper No. 11678.

Leuven, E. (2005), “The economics of private sector training: A survey of the literature”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 19, pp. 91-111.

Moore, M. J. and Viscuri, W. K (1988), “Doubling the estimated value of life: results using new occupational family data”, Journal of Public Policy Analysis and Management, 7(3), 476-90.

Smith, R. S. (1979), “Compensating wage differentials and public policy: a review”, Industrial and labour Relations Review, 32, 339-52.

Veljanvski, C. G. (1978), The Economics of Job Safety Regulation: Theory and Evidence: Part I – The market and Common Law Oxford Centre for Socio-Legal Studies. Wolfson College.