Introduction

The theory of reasoned action has been used to explain vegetarianism as a consumer trend. It suggests that shifts in consumer demand are explained by pre-existing attitudes (Gaol, Mars & Saragih 2014). If this philosophy is extrapolated to the vegetarianism trend analysis, the theory of reasoned action suggests that the rise in the number of vegetarians stems from people’s tendency to associate vegetarianism with good health. Therefore, respect for good health is an attitude that vegetarians have and that motivates them to embrace a lifestyle that supports the same values of improved human wellbeing (Davis & Melina 2014).

The motivation-need theory has also been used to explain vegetarianism as a consumer trend. It suggests that people purchase products to fulfill five levels of need, which are basic, safety, love/belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization (McGuffin 2016; Fallatah & Syed 2018). Vegetarianism is a basic human need because it is about food, which is at the lowest level of the Maslow model. The need for good health is also intertwined with food as a basic need because good health is dependent on it. Therefore, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that vegetarianism is informed by the need for people to be healthier.

Lastly, the psychoanalytic theory is another model that explains vegetarianism. It suggests that consumer trends are informed by how much they appeal to people’s feelings, hopes, and desires, as opposed to their rationality (Gunter & Furnham 2014). These basic principles of the theory postulate that an increase in the number of Chinese vegetarians is informed by its strong emotional appeal as opposed to its rationality (Bernstein 2018).

Stated differently, the consumption of meat products is rational but vegetarianism is more emotionally appealing because of its immense health benefits. Consequently, the trend is popular because it appeals to people’s emotions as opposed to logic.

Current Situation of Chinese Vegetarianism

An evaluation of the vegetarianism trend in China suggests that several demographic factors influence the trend. Age, gender, and intelligence are the two most impactful variables explaining the trend.

Gender and Education

Several researchers have reported significant gender variations among vegetarians (Appleby et al. 2016). For example, an American study, authored by Thomson (2014), suggested that 79% of vegetarians in the country were women. The study also postulated that gender differences in dedication, commitment, and health consciousness largely explained the low number of men who supported vegetarianism (Thomson 2014).

This gender divide is further highlighted by statistics, which show that women are 60% more likely to be vegan compared to men (Thomson 2014). Although gender differences predict vegetarianism, the education levels of both men and women also influence the trend. Notably, researchers have suggested that high levels of educational achievement are associated with vegetarianism, while low levels of education are linked with meat consumption (Stewart 2015).

The impact of education on a vegetarian diet can be explained by the improved access to information and knowledge about the benefits of vegetarianism among educated people, while those who have a low educational achievement have limited access to the same information. Therefore, high education levels increase access to information that supports the lifestyle.

Age

The increase in the number of people who identify with the vegetarianism lifestyle has grown in the past decade (Allès et al. 2017). According to some researchers, young people primarily support this lifestyle. A recent report authored by Marsh (2016) suggested that about half of all vegetarians were young people aged between 15 and 34 years. Comparatively, only 14% of vegetarians are aged over 65 years (March 2016).

Generally, these statistics show that vegetarianism is a trend that has been well received by younger people compared to their older counterparts (Campbell & Campbell 2016). This lifestyle may stem from the tech-savvy nature of younger demographics, which allows them to access information regarding the health benefits of vegetarianism (Cofnas 2018). Therefore, many young people are knowledgeable about its advantages and choose to change their lifestyles accordingly.

Intelligence

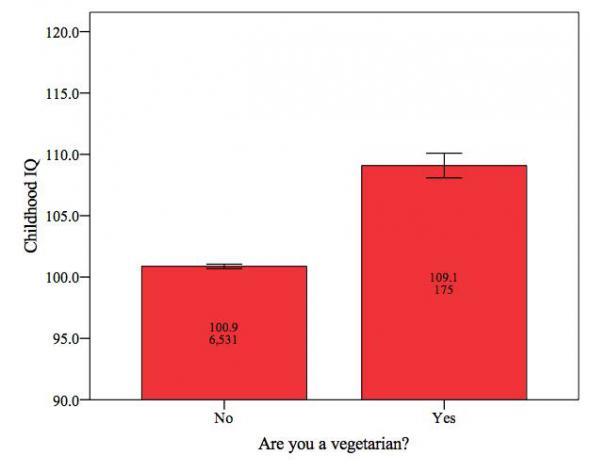

Another dimension of vegetarianism that has been explored by researchers is the role of intelligence in determining whether a person will be vegetarian, or not (Myles 2017). Broadly, this view has supported the idea that people who have high intelligence scores have a similarly high probability of being vegetarian compared to those who have low intelligence scores (Cai 2015).

For example, it is estimated that vegetarians have a mean intelligence quotient (IQ) of about 108, while people who consume meat products have a lower IQ of about 100 (Cai 2015). Figure 1 below shows that the difference in IQ levels between both groups of consumers is significant enough to support the assumption that IQ levels explain the vegetarian lifestyle.

Generally, the insights provided above show that intelligence, age, gender, and education explain vegetarianism. Nonetheless, there is a gap in the literature, which stems from the failure of researchers to contextualize these predictive factors among Chinese consumers.

Reference List

Allès, B, Baudry, J, Méjean, C, Touvier, M, Péneau, S, Hercberg, S & Kesse-Guyot, E 2017, ‘Comparison of sociodemographic and nutritional characteristics between self-reported vegetarians, vegans, and meat-eaters from the nutrinet-santé study’, Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1023-1024.

Appleby, PN, Crowe, KE, Bradbury, RC & Key, TJ 2016, ‘Mortality in vegetarians and comparable nonvegetarians in the United Kingdom’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 218-30.

Bernstein, R 2018, Top consumer behaviour theories. Web.

Cai, Y 2015, Does eating meat make people stupid. Web.

Campbell, TC & Campbell, TM 2016, The China study: revised and expanded edition: the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and the startling implications for diet, weight loss, and long-term health, BenBella Books, Inc., London.

Cofnas, N 2018, ‘Is vegetarianism healthy for children,’ Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 572-579.

Davis, B & Melina, V 2014, Becoming vegan: the complete reference to plant-based nutrition, comprehensive edition, Book Publishing Company, New York, NY.

Fallatah, RH & Syed, J 2018, A critical review of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Web.

Gaol, FL, Mars, W & Saragih, H 2014, Management and technology in knowledge, service, tourism & hospitality, CRC Press, New York, NY.

Gunter, B & Furnham, A 2014, Consumer profiles (RLE consumer behaviour): an introduction to psychographics, Routledge, London.

Marsh, S 2016, ‘The rise of vegan teenagers: more people are into it because of Instagram’, The Guardian. Web.

McGuffin, R 2016, Consumer loyalty to electricity suppliers: factors affecting consumer behaviour, GRIN Verlag, New York, NY.

Myles, A 2017, Science says vegetarians have higher intelligence & are more empathetic. Web.

Stewart, J 2015, Vegetarianism and animal ethics in contemporary Buddhism, Routledge, London.

Thomson, J 2014, ‘Veganism is a woman’s lifestyle, according to statistics’, Huffington Post. Web.