Introduction

The present paper attempts to critically analyse two CDP models, namely the Theory of Buyer Behaviour and the Consumer Decision Model, with a view to determine the extent to which they are vague and/or all-encompassing when applied to the postmodern hospitality industry.

The fields of consumer behaviour in general, and consumer decision-making process in particular, have increasingly attracted attention and intense investigation from marketing academics and mainstream practitioners from the sixties. During the last five decades, a multiplicity of models has been advanced for illuminating the behaviour of consumers’ in general decision-making scenarios (Erasmus et al. 2001).

Many of these consumer decision-making process (CDP) models are inspiring in scope and context, but their authentic efficiencies in explicating the behaviour of consumers have been substantially obscured by the fact that most research efforts have been focussed on explicit sections of the models rather than at the models in their entirety (Rau & Samiee 1981), and also by definitional, conceptual and measurement challenges (Ghosal 2005).

Overview of Consumer Behaviour in Hospitality Industry

Unlike in manufacturing-oriented contexts, the hospitability industry is guided by a unique set of characteristics, which include intangibility of services, inseparability of production and consumption, perishability of services, heterogeneity in service offerings, and human participation in the production process (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010).

This paradigm shift implies that consumption behaviour in hospitality settings is rarely directed by dominant CDP models which are mostly conceptualized under rationalistic, cause-effect, and economic discourses (Handlechner 2008), but by pluralism of styles (Williams 2003).

More importantly, postmodern consumerism, coupled with globalization of products as well as hedonistic discourses, have generated new options for experiences and self-expression not only in making consumption decisions but also, and more nascent, in driving consumption in hospitality organizations across geographical landscape, cultural orientations and socioeconomic statuses (Tsiotsou & Wirtz 2012).

A number of factors that impact on customer behaviour in hospitality industry are briefly evaluated in the subsequent section.

Postmodern Consumerism within the Hospitality Industry

The arrival of postmodernism and its characteristic consumer culture has heralded a new era that is “…associated with hedonism, narcissism, nihilism, decadence, instant gratification and social control” (Dermody et al. 2009, p. 316).

It is therefore not surprising that, as these authors observe, contemporary consumers have not only grown to love their freedom and to view it as a discrete component of their lifestyle, but they also view themselves as having no compulsion but to self-indulge through a pluralism of styles.

Consumerism has been linked with approaches for convincing consumers to expand their needs and wants (Bareham 2004), enticing consumers to overconsume through taking advantage of their insecurities, anxieties, impulsiveness and suffering (Dermody et al 2009), consumption as a means for happiness and wellbeing (Toepel 2011), and exploiting consumers’ emotions and feelings by accentuating the symbolic value of products and services at the expense of their functional value (Yani-de-Soriano & Slater 2009).

Consequently, it becomes difficult to delineate a pathway of consumer behaviour in postmodern contexts.

It has been noted in the literature that postmodern consumerism fosters a hedonistic impulse by feeding consumer fantasies associated with simulation and implosion (Ritzer 1999).

It is therefore interesting to note that for an increasing number of people who visit hotels and other hospitality facilities, the influence of hedonic consumption is mounting, and with it, an increase in individuality and distinctiveness that is difficult to generalize under many of the current phase-oriented CDP models (Christensen et al. 2005).

Consequently, consumer behaviour nowadays tends to assume variable and disloyal dimensions as consumers are urged to not only experiment with new products and services but also to choose from a multiplicity of different experiences that are hard to standardize due to richness of choice (Bauman, 1993; Erasmus et al. 2001).

It is, therefore, safe to argue that consumer behaviour in postmodern era has relatively assumed a deconstructivist approach that is more pragmatic oriented in decision-making and arguably less cognitively bound.

As a result, the postmodern market is typified by hedonism, hyperreality, fragmentation, globalization of products and services, and an inclination for production and consumption to be reversed (Christensen et al. 2005).

Hedonism

The mounting consciousness of hedonic consumption among modern consumers has promoted not only pleasure-seeking behavior as the only intrinsic good but also luxury consumption and satisfaction to fulfill the diverse needs of consumers (Handlechner 2008 Williams 2003).

In the hospitality industry, the postmodern consumer is embracing the richness of choice, traditions, and styles to sample products and services that will enable them to achieve the intrinsic good.

For example, in making a restaurant choice, consumers always attempt to get something out of it and in the context of hedonism, it is a pleasure, implying that a preference for happiness and satisfaction, in the very broadest sense, is what structures their lives.

In the words of Handlechner (2008), “…it is more likely that many consumers are not fully aware of the omnipresence of consumption on (post) modern society and therefore they assume that they are in control of their consumption” (p. 12).

As a direct consequence, therefore, it is increasingly becoming difficult for industry players to predict behavior since consumers are guided by the unconventional urge to experiment on new products and experiences (Christensen et al. 2005).

Fragmentation of Products and Services

The absence of a central ideology to guide postmodern consumption patterns gives rise to a wealth of norms, values, beliefs and lifestyles that are adhered to by consumers in the quest to fulfill their insatiable appetite for products and services.

To satisfy this intensifying demand for unique experiences, practitioners within the hospitality industry are increasingly segmenting or fragmenting their product and service offerings (Firat et al. 1995), making it increasingly challenging to evaluate consumer behavior and decision-making process objectively.

More importantly, the post-modernity orientation is on record for enhancing the production of smaller niche markets in fragmented dispositions, not only making it difficult to successfully evaluate behavior using the current models but also eating into the profitability of hospitality organizations (Van Raaij 1993).

This is largely caused by the popular view in fragmented markets that there is no singular definition of reality and that causality is often multifaceted and not clear.

Hyperreality

According to Christensen et al. (2005), “…hyperreality implies that the hype or the simulation is seen as, and becomes, more real than the reality it represents” (p. 158).

In most hospitality settings, experiences are passed as real and authentic for purposes of driving consumption while in actual sense they are light and empty (Van Raaij 1993), leading to loss of control, consistency and predictability on the part of consumers (Christensen et al. 2005).

Available literature demonstrates that hyperreality is to a large extent propelled by the voracious appetite of consumers to sample disjointed experiences and episodes of experience, leading practitioners in the hospitality industry to simulate some of the experiences and pass them as real while they are mere simulations in the image of hypes (Firat et al. 1995).

Globalization

Globalization, according to Firat (1997), “…is considered to be the presence of the same lifestyles, products, consumption patterns, and cultural experiences across the globe, across many economically affluent or economically poor countries of the world” (p. 178).

Globalization and the ensuing convergence of technology have assisted to neutralize geographical barriers that supported economic nationalism and chauvinism.

Consumers are no longer consuming products and services based on their ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Van Raaij 1993), though some scholars still maintain consumption patterns are still predetermined by the consumer’s culture, and that globalization has no capacity to standardize consumer behavior (Firat et al. 1995; Williams 2003).

More importantly, the intangible nature of services within the hospitality industry necessitates comprehensive individualized marketing and customized services for the customer to experience the unique and superior value.

In this context, it can be argued that the idea of global hospitality organizations to increasingly standardize and customize their products and service offerings is paradoxically based on the fact that these organizations must deal with cultural variations that to a large degree influence consumer’s mind-sets and buying behaviors (Williams 2003).

Consumer Behavior and Decision-Making Process (CDP) Models

Engel, Blackwell and Miniard (1995) cited in Williams (2003) define consumer behavior as “…those activities directly involved in obtaining, consuming and disposing of products and services including the decision processes that precede and follow those actions” (p. 8).

Extending this definition, Handlechner (2008) argues that the study of consumer behavior potentially deal with how people make decisions to buy and use products and services in their role as consumers, and how these decisions affect or influence their actions.

Consequently, “…the consumer decision-making process is the process by which individuals select from several choices, products, brands or ideas” (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010, p. 7).

Understanding the consumer decision-making process, along with the needs, preferences, lifestyles and other variables that influence behavior, is a fundamental concern of successful planning and marketing, not only in the hospitality industry but also in other sectors.

Extant research demonstrates that most CDP models consist of explicit stages through which the consumer passes as they make consumption decisions (Macinnis & Folkes 2010). A review of the most used CDP models shows that the consumer passes through several stages while making consumption decisions, which include:

- need identification,

- information search,

- appraisal of available alternatives,

- purchase/consumption decisions,

- post purchase decisions (Teng & Barrows 2009).

Handlechner (2008) is of the opinion that “…the consumer of the restaurant services goes through most of the stages of the decision-making process model before he or she decides if and which restaurant to choose according to the importance for himself and his social environment” (p. 13).

However, this opinion has received substantial criticism from other quarters, with Abdallat & El-Emam (n.d) arguing that it is wrong for marketers to rely on phase-oriented models to explain consumer behavior due to their vagueness and lack of methodical approach, while Dermody et al. (2009) posits that people are not bound by phases while making consumption decisions; rather they make decisions based on their lifestyle, status, or just because they are seeking pleasure.

Similarly, Lovelock & Wirtz (2010) criticizes the phase-oriented rationalistic models due to their all-encompassing nature while assuming that consumers must pass through the stages in sequence; however, it has been demonstrated that some steps are skipped depending on the consumer’s level of involvement.

To this effect, the justification for conducting this evaluation and critique derives from the evolving nature of consumer decision-making in response to the postmodern and fragmented nature of consumer behavior (Dermody et al. 2009), economic uncertainty and mounting competitive pressures (Macinnis & Folkes 2010), and the ever-shifting decision environment that makes it increasingly more challenging to “fit” modern decision-making realities to existing models (Teng & Barrows 2009).

More importantly, according to these authors, the increasing complexity of consumer decisions coupled with the inability of some of the consumer decision-making models to encompass effectively the waves of information associated with contemporary decision contexts makes a compelling case for critical evaluation and analysis.

Aim and Objectives of the Study

Aim

The present paper aims to analyze and critique two CDP models – Theory of Buyer Behavior and the Consumer Decision Model – with a view to determine the extent to which they are vague and encompassing when applied to postmodern hospitality industry.

Objectives

The study sets out to achieve the following objectives:

- To critically analyze available literature on consumer behavior and CDP models as they relate to the hospitality industry;

- To identify, analyze and critique the Theory of Buyer Behavior and the Consumer Decision Models to explicate the extent to which they are vague and all-encompassing when applied to the hospitality industry, and;

- To outline possible recommendations that could be used to better understand consumer behavior and decision-making process within the hospitality industry.

Methodology

Research Philosophy

The present study made full use of the positivist research philosophy and the deductive research approach to critically analyze and critique the selected CDP models, with the view to determine their level of vagueness and inconsistency, particularly when applied to hospitality contexts.

In the positivist research paradigm, according to Krauss (2005), “…the object of study is independent of researchers; knowledge is discovered and verified through direct observations or measurements of phenomena; facts are established by taking apart a phenomena to examine its parts” (p. 759).

This research philosophy enabled the researcher to examine the parts of the two models using the deductive approach (from the more general to the more specific) with the view to establish and collate the noted weaknesses of the models as applied in a postmodern hospitality context.

Data Collection

The study utilized secondary research to collect relevant materials from third-party sources and other information that had been previously collected for some other reason but archived in popular academic databases, such as Ebscohost and Emerald, among others.

The justification for using secondary research as opposed to primary research in collecting the relevant information to undertake this study is premised on the facts that it requires less time and resources to undertake secondary research, and data retrieved from various databases and credible websites are easy to access and assist the researcher to effectively answer the stated research objectives (KnowThis.Com 2012).

Limitations to the Study

The researcher was inhibited by time and budgetary resources to institute a more comprehensive study that could have shed light on how the various variables included in the two sampled CDP models interact with each other to inform decision-making processes within the hospitality industry, and the various factors that come into play to limit the models from effectively capturing trends of consumer behaviour within the industry.

According to Handlechner (2008), “…hospitality services are not finite; they are chaotic and unpredictable, changing in nature for each consumer on a continuous basis, wherein even the basic set of products evokes different responses in different consumers” (p. 13).

Consequently, a more comprehensive study involving primary research could have elucidated new insights into how these models are effective in explaining customer behaviour and decision-making process.

Analysis & Critique

Theory of Buyer Behaviour

The Theory of Buyer, also known as Howard & Sheth Model, is premised on the assumption that “…the consumer is an information processor who engages in a rational, scientific, deliberate and cognitive process leading to a purchase choice” (Bareham 2004 p. 162).

This model, which is phase-oriented, assumes that the consumer assembles all the alternatives on offer, applies rationalistic rules of self-interest in evaluating the other options, uses explicit cognitive processing, and avails equal attention to each option, before proceeding to make a purchase or consumption decision (Toepel 2011).

In other words, the model “…provides a sophisticated integration of the various social, psychological and marketing influences on consumer choice into a coherent sequence of information processing” (Bray 2008, p. 10).

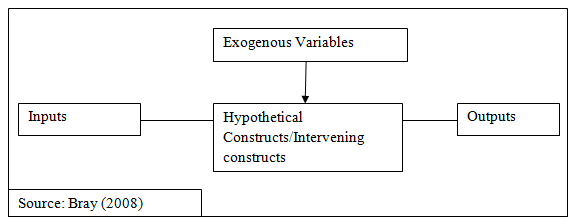

As can be seen in Figure 1, the major components of the Theory of Buyer Behaviour include: Inputs, exogenous variables, hypothetical constructs and outputs.

Input variables are the environmental stimuli that the consumer is subjected to, and is conversed from a multiplicity of sources, which include significative incentives (actual elements of products, services and brands that the consumer confronts), symbolic stimuli (representations of products, services and brands as constructed by marketing practices through such means as advertising, promotional activities, etc), and social stimuli (influence directed on the consumer from family members, peers and other reference groups).

The model further notes that the influence of the mentioned stimuli is internalized by the consumer before making purchase or consumption decisions (Bray 2008).

The hypothetical constructs are classified into two main categories, namely:

- perceptual constructs (sensitivity to information, perceptual bias, and search for information),

- learning constructs (motive, evoked set, decision mediators, predispositions, inhibitors, and satisfaction).

It should be noted that while the perceptual constructs functions to control, filter and process the stimuli that are received by the consumer, the learning constructs functions to influence the level to which the consumer considers future purchases or consumption decisions, and look for new information (Bray 2008).

This author further notes that “…in situations where the consumer does not have strong attitudes they are said to engage in Extended Problem Solving (EPS), and actively seek information in order to reduce brand ambiguity” (p. 13).

In such scenarios, the consumer will, in addition, embark on extended deliberation before making a decision on which product/service to purchase/consume or indeed, whether to make any purchase/consumption decision.

However, as the product or service becomes more familiar to the consumer, these processes will be commenced less carefully “…as the consumer undertakes Limited Problem Solving (LPS) and eventually Routine Problem Solving (RPS)” (Bray 2008, p. 13).

The exogenous variables in the Theory of Buyer Behaviour delineate a number of external variables that have the capacity to influence consumer purchase/consumption decisions substantially. These variables are however not clearly outlined in the model as they depend, in large part, on the individual consumer and contain the history of the consumer up to the beginning of the period of observation (Bray 2008).

Lastly, the output variables characterize the consumer’s response and follow the progressive steps to purchase/consumption, including attention, comprehension, attitudes, intention, and purchase behaviour (Farley & Ring 1970).

Critique

When this model is applied to the hospitality industry, it has a significant contribution in as far as suggesting that individual attitude influences purchase/consumption behaviour only through intention.

However, as noted by Bray (2008), there is “…widespread questioning of the model’s validity due to the lack of empirical work, employing scientific methods, examining the organisation of the model and the inclusion of the constructs” (p. 14).

Additionally, due to the unobservable nature of a multiplicity of the hypothetical or intervening constructs unambiguous assessment of how these variables interact to influence consumer decision-making process is often challenging to outline (Cova & Cova 2009).

As observed elsewhere, hospitality services are not finite (Handlechner 2008), thus it becomes increasingly difficult to use linear models of consumer behaviour, such as the Howard and Sheth Model, to explain decision-making processes. It is well known that a lot of consumption in hospitality organizations depends on motivation, perception and habit.

Consequently, “…further understanding today’s hedonistic consumers means understanding how consumers use fantasising to generate feelings” (Handlechner 2008, p. 13).

Here, non-linear models may prove to be less vague and more valid in exploring such behavioural orientations since they are qualitative and explain thought processes as heuristic mechanisms rather than logical, phase-oriented and cognitive processes (Bareham 2004).

While it is commendable that the Theory of Buyer Behaviour makes a concerted effort to assist marketing practitioners understand the specific influence of exogenous variables on consumer behaviour (Bray 2008), postmodern perspectives on consumption patterns demonstrate that consumers are much fickle and unpredictable than what is construed in the model (Bareham 2004).

The all-encompassing orientation of the model, demonstrated by its linear stages, therefore implies that it is incapable of providing useful insights required by decision-makers within the hospitality industry, in large part due to the fact that consumers not only use a multiplicity of decision strategies to select among alternatives but the plans are socially constructed and context-dependent (Teng & Barrows 2009).

Consequently, it can be argued that consumers visiting a hotel to have lunch engage different rules for different occasions, not mentioning that hospitality consumers no longer represents a centred, unified, consistent self-image, but a fragmented and fluid set of self-images that are hard to quantify or explain using linear models such as the Theory of Buyer Behaviour (Farley & Ring 1970).

Overall, conceptualizing the hospitality consumer as a constituent of a characteristically static market segment as is the case with the Theory of Buyer Behaviour renders vague any attempt to understand behaviour; rather, consumers must be viewed as conscious and empowered agents who employ the symbolic system of postmodern consumption within the hospitality industry to establish class differences and personal identities (Hansen 2005).

The Consumer Decision Model

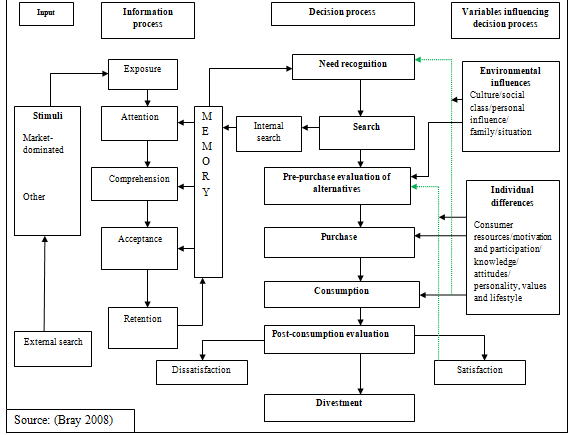

The Consumer Decision Model, developed in 1968 by Engel, Kollat and Blackwell, is yet another linear model of decision making structured the following phases of decision making: need recognition; use of internal and external means to search for information; assessment of alternatives; purchase decision; post-purchase reflection, and; divestment (Bray 2008; Macinnis & Folkes 2010).

Additionally, the model suggests that the decision-making process is influenced by two important aspects: “…firstly stimuli is received and processed by the consumers in conjunction with memories of previous experiences, and secondly, external variables in the form of either environmental influences or individual differences” (Bray 2008, p. 15-16).

In need recognition, which is the first stage of the model, the consumer enthusiastically recognizes a discrepancy between their current state and some other pleasing alternatives, principally stimulated by an interaction between the processed stimuli inputs on the one hand, and environmental and individual constructs on the other. The predisposition triggers the consumer to move into the next stage, which entails the search for relevant information about a particular product or service.

One of the core tenets of this model in this stage is the supposition that the intensity of information exploration is fundamentally dependent on the scope and context of problem-solving, with new or elaborate consumption challenges being subjected to thorough external information explorations, while simpler challenges may depend exclusively on light-weight internal exploration of prior consumer behaviour (Dermody et al. 2008; Decrop 2006).

The consumer then transits into the third phase, which entails evaluating alternative consumption choices while relying on a conventional set of beliefs, attitudes, value systems and consumption intentions and predominantly influenced by both individual and environmental variables.

An important finding here is the realization that this model portrays intention to consume as the only precursor to consumption behaviour.

Additionally, while the environmental and individual contextual factors are to a large extent perceived to influence purchase decisions, it is also noted in the relevant literature that the term ‘situation’ is premeditated as an environmental factor (DiMaggio 1995), and may imply to such variables as time pressure or monetary constraints that may interact to prevent the consumer from achieving their purchase/consumption intentions (Luke 1991).

The other stages comprise the actual consumption, post-consumption evaluation (to grant feedback functionality to the consumer) and divestment (Bray 2008).

Critique

The Consumer Decision Model draws its major strength from its capability to evolve to include qualitative variables that have been used elsewhere to explain consumer behaviour. For instance, the model has been effective in integrating individual variables of motivation and involvement to explain behaviour (Toepel 2011), as well as environmental constructs of social class, family relations and family (Whetten 2003).

These variables are to some extent, useful in explaining how consumers interact with particular hotel organization in their quest to fulfil their hedonic consumption behaviours.

However, it is evident that the individual and environmental constructs illuminated in the model remain vague due limited theoretical and methodical background (Erasmus et al 2001), inability to specify the exact cause-and-effect relationships between the variables and in relation to how they influence customer choices within the hospitality setting (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010; Shao et al. 2006), and their predisposition of being too restrictive to sufficiently accommodate the variety of consumer decision situations in a hospitality environment characterized by shifting consumption trends and ever-increasing competitive pressures (Bareham 2004; Tsiotsou & Wirtz 2012).

Again, researchers are reluctant to buy the assertion that consumer behavior in hyperreal contexts as demonstrated in the hospitality industry can be explained through rationalistic, stage-oriented models such as the Consumer Decision Model (Macinnis & Folkes 2010). Williams (2002) cited in Bareham (2004) “…recently chronicled how the significance of simulations and hyperreality are a key attraction to the consumer and how there are plenty of examples to illustrate this in the world of tourism and hospitality” (p. 163).

This author provides the example of Luxor Casino and Hotel in Las Vegas, which the practitioners have simulated to resemble ancient Egypt while in actual sense, it is not.

In the view of postmodernists it is not possible for this model to explain consumer behaviour in simulated hospitality environments that claim to be authentic while they are mere simulations (Teng & Barrows 2009), and in a consumption environment where the consumer is no longer consistent in their behavior and does not fit the stereotypes that phase-led models would have us believe (Lehmann et al. 1974).

This ultimately implies that the hospitality consumer preferences are not simple and cannot be effectively explained or predicted by developing stages of decision-making as premised in the Consumer Decision Model; rather their preferences are more dependent on the context of choice and the products/services available (Toepel 2011).

Conclusion and Recommendations

To conclude, it is important to underline the fact that conventional CDP models may often fail to provide hospitality policymakers and industry players with a sufficiently illuminating depiction of how consumers within the industry go about making their consumption choices (Ghosal 2005).

The researcher, therefore, contends that the discussed CDP models are ineffective in explaining behavior of the consumer within the hospitality industry, and may, thus, lead to ineffective marketing policies due to gaps and methodical problems, as well as their cognitive and mechanistic way of explaining behaviour (Firat 1997).

Consequently, it is recommended that academics and practitioners should come up with new additions in the models that seek to portray the consumer as an emotional being, focused on realizing pleasurable experiences, creating identities, and developing a sense of belonging through consumption (Hansen 2005).

The new paradigms, it is widely believed, must also have the capacity to provide enough variety of contextual explanations that can be used to distinguish today’s postmodern consumer and a whole new set of influences without reference to a standardized expectation.

Reference List

Abdallat, M.M.A & El-Emam, H.E n.d., Consumer behaviour models in tourism. Web.

Bareham, J.R 2004, ‘Can consumers be predicted or are they unmanageable, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, vol. 16 no 3, pp. 159-165.

Bray, J 2008, Consumer behaviour theory: Approaches and models. Web.

Cova, B & Cova, V 2009, ‘Faces of the new consumer: A genesis of consumer governmentability’, Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English Edition), vol. 24 no. 3, pp. 81-99.

Christensen, L.T, Torp, S & Firat, A.F 2005, ‘Integrated marketing communication and postmodernity: An odd couple? Corporate Communications: An International Journal, vol. 10 no. 2, pp. 156-167.

Decrop, A 2006, Vacation decision making, CABI Publishing, Wallingford, Oxon.

Dermody, J, Hanmar-Lloyd, S & Scullion, R 2009, ‘Shopping for civic values: Exploring the emergence of civic consumer culture in contemporary western society’, Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 36 no. 1, pp. 316-324.

DiMaggio, P.J 1995, ‘Comment on what theory is not’, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 40 no, 3, pp. 391-397.

Erasmus, A.C, Boshof, E & Roesseau, G.G 2001, ‘Consumer decision-making models within the discipline of consumer science: A critical approach’, Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, vol. 29 no. 3, pp. 82-90.

Farley, J.U & Ring, W 1970, ‘An empirical test of the Howard-Sheth model of buyer behaviour’, Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 7 no. 4, pp. 427-438.

Firat, A.F, Dholakia, N & Venkatesh, A 1995, ‘Marketing in postmodern world’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 29 no. 1, pp. 40-56.

Firat, A.F 1997, ‘Educator insights: Globalization of fragmentation – A framework for understanding contemporary global markets’, Journal of International Marketing, vol. 5 no. 2, pp. 77-86.

Ghosal, S 2005, ‘Bad management theories are destroying good management practices’, Academy of Management Learning & Education, vol. 4 no. 1, pp. 75-91.

Handlechner, M 2008, Consumer behaviour in the hospitality industry, GRIN Publishing GmbH, Munich.

Hansen, T 2005, ‘Perspectives on consumer decision making: An integrated approach’, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, vol. 4 no. 6, pp. 420-437.

KnowThis.Com 2012, Secondary research – Advantages. Web.

Kraus, S.E 2005, ‘Research paradigms and meaning making: A primer’, The Qualitative Report, vol. 10 no. 4, pp. 758-770.

Lehmann, D.R, O’Brien, T.V, Farley, J.U & Howard, J. A 1974, ‘Some empirical contributions to buyer behaviour theory’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 1 no. 3, pp. 43-55.

Lovelock, C & Wirtz, J 2010, Services marketing, 7th Ed, Prentice Hall, London.

Luke, T.W 1991, ‘Power and politics in hyperreality: The critical project of Jean Baudrillard’, Social Science Journal, vol. 28 no. 3, pp. 347-356.

Macinnis, D.J & Folkes, V.S 2010, ‘The disciplinary status of consumer behaviour: A sociology of science perspective on key controversies’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 36 no. 6, pp. 899-914.

Shao, W, Lye, A & Rundle-Thiele, S 2006, ‘Decisions, decisions, decisions: Multiple pathways to choice’, International Journal of Market Research, vol. 50 no. 6, pp. 797-816.

Teng, C.C & Barrows, C.W 2009, ‘Service orientation: Antecedents, outcomes, and implications for hospitality research and practice’, The Service Industry Journal, vol. 29 no. 10, pp. 1413-1435.

Toepel, V 2011, ‘Monitoring consumer attitudes in hospitality services: A market segmentation’. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, vol. 11 no. 1, pp. 75-94.

Tsiotsou, R.H & Wirtz, J 2012, “Consumer behaviour in service context”, In V. Wells & G. Foxall (eds), Handbook of Developments in Consumer Behaviour, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Northampton, MA, pp. 147-201.

Whetten, D.A 1989, ‘What constitutes a theoretical contribution?’ Academy of Management Review, vol. 14 no. 4, pp. 490-495.

Van Raiij, W.F 1993, ‘Postmodern consumption’ Journal of Economic Psychology, vol. 14 no. 3, pp. 541-563.

Williams, A 2003, Understanding the hospitality consumer, 1st ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Yani-de-Soriano, M & Slater, S 2009, ‘Revisiting Drucker’s theory: Has consumerism led to the overuse of marketing? Journal of Management History, vol. 15 no. 4, pp. 452-466.