Contracts are agreements between two (or more) parties, accepted voluntarily and leading to legal consequences if the prescribed conditions are not met. Usually, they “help to solve some of the basic challenges of cooperation for humans”. Contracts are always made when there is a benefit for one of the parties while fixing the other party’s losses. A contract cannot be entered into by force, with the threat of blackmail or persuasion, and persons must be of sound mind when entering into a contract, wherever it is signed. In the event of a breach of contract, the parties are subject to legal protection, and their case is subject to review.

Contract law enforces such promises and may differ from state to state. Consideration and mutual agreement are considered the main elements of the contract. Consideration implies the presence of favor or action by one person that he or she can exchange for a reward from another person. If both persons entering into the contract consider their benefits to be sufficient, the contract successfully enters into force.

Usually, contracts are supported by two theories, the first of which relates to benefits-costs. Contracts are made when both parties may suffer losses but decide to help each other on favorable terms. Simplifying, this model can be described as ‘one performs an action, and the other will respond positively, although he or she may harm.’ The second theory relates to a bargain, transaction, and exchange. In this exchange, one person makes a promise to another after he has been induced to make this promise.

Most often, contracts are considered by private law, which can prevail over the norms established, in general, in the states and over statutory law. Private law does not emphasize the signing of papers and the evidence of professional persons (auditors, notaries). Private law usually uses the concepts of trust, mutual, and voluntary consent and tries to fix that both parties enter into a contract in a sober mind. Contract law sometimes governs transactions for the purchase and sale of real estate or the rental of real estate, although there are many inaccuracies, and tenants and landlords do not always use contracts.

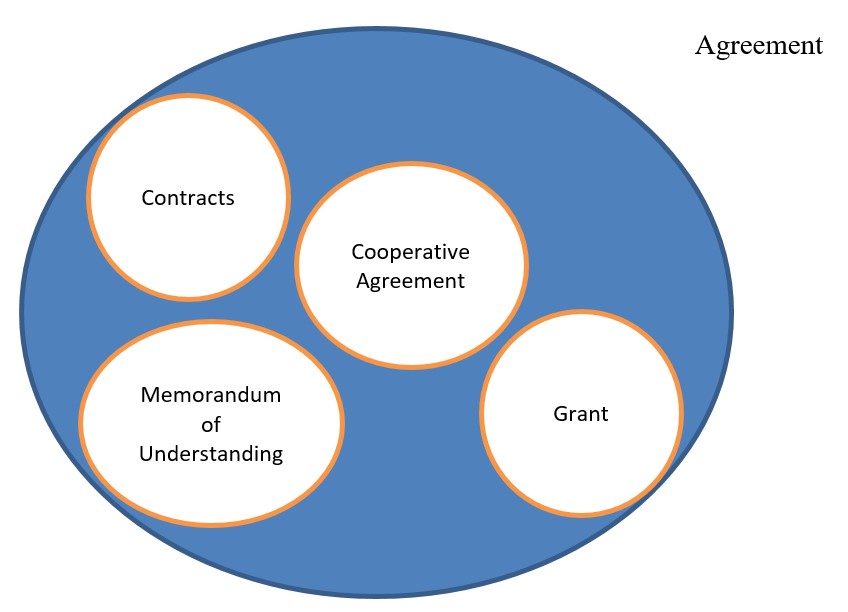

An agreement is the broadest concept logically and includes contracts and other types of agreements based on shared benefits. If people depict the concepts of an agreement and a contract on Euler circles, we can ensure that a contract is only a particular case of an agreement (see Figure 1). Euler circles geometrically depict relationships between a set (agreements) and its subsets (contracts, memorandum of understanding, grants, and cooperative agreements). These were taken as examples of other subsets to demonstrate that contracts are not the only subset in agreements. The agreement can be interpreted both in the legal field and many others.

In a broad sense, lawyers consider an agreement to be a manifestation of two or more persons’ mutual and voluntary consent. Consent is, in fact, an even broader concept than agreement. Therefore, very often in the courts, there are quarrels on whether people (defendant or plaintiff) nevertheless gave consent or permission for one or another committed action. Most courts in the states hold that there is no legal process or liability following the agreement. An agreement is an expression of understanding on any level, sometimes even on a symbolic or friendly level. For example, dormmates may enter into agreements to use common areas or cleaning services. There is also a common expression, ‘gentleman’s contract,’ which does not provide for legal obligations.

References

- Goodenough, O. R. (2020). Integrating smart contracts with the legacy legal system: A US perspective. Blockchain, Law and Governance, 191–203.

- Lucy v. Zehmer, 196 Va. 493, 84 S.E.2d 516 (Va. 1954).

- Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 1 (1981).