Introduction

Researchers agree that successful businesses depend on the effective management of corporate culture, employee motivation, and workforce diversities (Dipboye & Halverson 2004; Ackroyd & Crowdy 1990). This agreement stems from successive years of research, which have studied employee-company relations.

For example, successive neo-liberal governments in the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) have given a lot of freedom to companies and managers to redefine the working conditions and practices that affect employee-company relations (Ogbonna & Wilkinson 2003).

Practically, governments have influenced employee-company relations by loosening the restrictions on labour union powers and limiting the extent that company employees could oppose managerial strategies.

The same governments have achieved this objective by reducing competitive pressures on companies and eliminating widespread redundancies in the corporate space (Ogbonna & Wilkinson 2003). Through these legislative interventions, since the early eighties, many companies have enjoyed the freedom of adopting different managerial theories for improving employee-company relations.

The adoption of the above governance frameworks requires the careful implementation of managerial strategies to meet company goals because the process of managing corporate culture, employee motivation, and workforce diversity is complex.

Based on this analysis, this paper investigates different considerations that company managers need to be aware of when they manage corporate culture, employee motivation, and workforce diversity programs. To explore these issues, this paper divides into three sections that investigate corporate culture issues, employee motivation issues, and diversity issues. They outline below

Managing Corporate Culture

Influence of External Factors on Organisational Culture

As organisational heads create distinct cultures that differentiate their organisations from others, they need to be aware of the influence of the societal culture in their organisations. Indeed, organisations cannot operate in isolation. They are, therefore, subject to external organisational factors that often influence employee perceptions and attitudes in the organisation.

An experiment by Ackroyd & Crowdy (1990) to investigate the behaviours of employees of a Cincinnati slaughterhouse showed that most of the employees experienced social stigma because of the nature of their work (people thought their jobs were dirty and involved killing living animals). The experiment revealed that the employees did not allow these negative societal perceptions to affect them (Ackroyd & Crowdy 1990).

Instead, the negative societal perceptions of their work helped them to develop an interesting sub-culture that made them exceptionally proud of their work (realism and aggressive masculinity characterised this subculture).

Referring to this outcome, Ackroyd & Crowdy (1990) said, “This subculture helped the employees to work hard and fast, to ignore the very considerable demands and dangers of doing the job, to be indifferent to the harassments and blandishments of co-workers and the public alike” (p. 10).

The development of such a subculture appeals more to the influence of external forces than internal management interventions (in influencing employee behaviour) (Jackson & Carter 2007). Its significance to the employees was the creation of an insulating buffer that would protect them from external prejudice (from the society).

This experiment also showed that all employees in the organisation shared the same job security concerns because they did not experience primary dissent from other employees and the society.

Through the realisation that they need to be tough, to conduct their activities (efficiently), the researchers considered their bravery and creation of a new sub-culture as an attempt by the employees to import a “latent culture” into a “manifest culture” (Ackroyd & Crowdy 1990).

However, it is essential to understand that the creation of the resilient subculture does not stem from the vitality of the latent subculture, but from the working practices of the employees, based on societal evaluations of their work.

The above analysis shows the significance of understanding the effect of latent cultures on corporate cultures. Managers, therefore, need to consider how an organisation’s culture aligns (or clashes) with the societal culture. An analysis of the effects of external forces in the development of the US corporate culture also explains this fact.

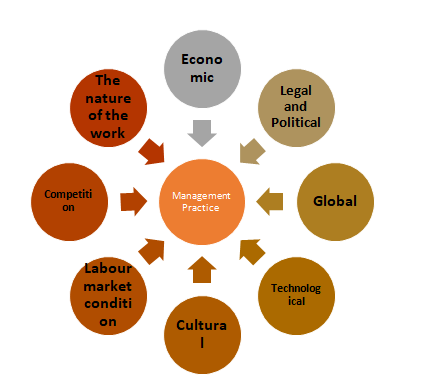

Indeed, based on the diagram below, it is easy to point out that the development of the American corporate culture, in the 1980s, depended on several external factors, including the nature of the work, competition from other countries, labour market conditions, societal culture, technological development, global business dynamics, legal and political environment, and economic conditions.

Figure One: External factors that affected the development of the US corporate Culture (Source: Peters & Waterman 1982)

To further elaborate the influence of some of the above factors in the American corporate culture, it is critical to highlight that business developments in Japan greatly influenced America’s corporate culture development. For example, the fierce competition from Japanese products made American companies struggle to maintain their market (Peters & Waterman 1982).

Furthermore, increased competition from Japan made it difficult for American companies to shift their production processes overseas.

A legal and political analysis of the above diagram also shows that although the neo-liberal government, of the time, created increased freedoms for managers to redefine employee-organisational relationships, mistrust, and the opposition to governance systems (that started in the 1970s) hindered these reforms (Peters & Waterman 1982).

Lastly, from a cultural perspective, the role of Japan’s culture in informing the country’s success created renewed hope among American businesses that their national culture would equally yield the same results.

Comprehensively, most studies have compared East and West managerial practices to understand how corporate cultures affect employee success (Ogbonna & Wilkinson 2003).

Peters & Waterman (1982) add that Japan’s influence on America’s corporate culture has increased pressure for American companies to link company productivity to American culture (to achieve the same efficiencies that Japanese companies enjoy).

However, unique cultural practices in America suggest that America’s culture of individualism has introduced unique dynamics to employee behaviour in the workplace (Peters & Waterman 1982). For example, the highly individualistic culture in the US has created a sense of accountability in the country (aimed at increasing employee productivity).

This way, employees perceive their success and failures as their personal responsibility. This culture has also introduced new benchmarks for defining corporate success – personal, economic, and consumer success.

The American cultural direction shows a close connection with neo-human relations that focus on employee self-actualisation goals (Rose 1990). This paradigm supports employee productivity by linking their performance to the actualisation of personal goals (Rose 1990).

The above analogy shows that external factors could heavily influence corporate cultures. Therefore, while managers strive to implement and teach the dominant organisational culture on employees, they should do so after considering how this culture integrates with other cultures.

Conceiving the implementation of the manifest culture without considering the influence of the latent culture may, therefore, lead to unforeseen outcomes, as observed from the slaughterhouse case study and the development of the American culture (discussed above). Although the outcome of the case study is positive, it is crucial to say that this may not always be the case.

Public Assertions of Vision and Corporate Values

In line with the goal of developing corporate cultures, organisations often profess unique visions and corporate values that differentiate them from other organisations. Modern managers are, therefore, quick to assert organisational values that inform their corporate cultures.

However, as Dipboye & Halverson (2004) observes, this trend may create the opportunity for inaction among employees. This possibility mainly exists for organisations that charismatic leaders head.

Dipboye & Halverson (2004) also warn that charismatic leaders may be the drivers for organisational inaction because they take pride in making lofty expressions of what they believe in, without following them with action. To support this view, Dipboye & Halverson (2004) say, “weighty pronouncements on how discrimination will not be tolerated, or how diversity is a key-value, can introduce inaction” (p. 151).

Inaction creeps into such organisations because many leaders make these lofty statements as a cover-up for organisational and personal flaws. Although most of such leaders may make outright lies about their commitment to uphold the spirit of the organisational culture, Dipboye & Halverson (2004) believe they adopt very subtle approaches when doing so.

An interesting dynamic to this analysis is the fact that when most organisational leaders make egalitarian pronouncements about organisational vision and values, they provide a moral licence for employees to practice discriminatory activities in the organisation, so long as these activities support their goals and vision.

An experiment by Dipboye & Halverson (2004) affirmed the above fact. The researchers sampled a group of female respondents and asked them common social questions, such as, if most women required a man to protect them, if men were more emotionally suited to participate in politics, and if most women were better off conducting home duties.

The use of the word “most” was strategic to the formulation of these questions because it informed the findings of the researchers. Dipboye & Halverson (2004) found out that equal assertions encouraged the respondents to discriminate other people. A deeper analysis of this fact reveals that egalitarian assertions provide employees with a licence to discriminate other employees.

Dipboye & Halverson (2004) also revealed that egalitarian assertions have a negative/opposite effect on employees because managers perceive such assertions as codes for defining employee conduct, to no avail. Therefore, by stating an organisation’s culture/position, they do not see the need for following up on employee performance.

This reason explains why most companies that do not support discrimination, or prejudice, still report cases of the same. Similarly, organisations that claim to uphold employee diversity still tolerate prejudicial practices.

It is therefore interesting to see that vision and mission statements, that are supposed to guide organisational actions and employee behaviours, have a counterproductive effect of failing to make employees act or live up to their spirit.

From this analysis, clearly, public assertions of visions and corporate values lead to the development of subtle forms of inaction in the workplace, where few organisations admit any prejudice regarding their employee appraisal procedures, or corporate diversity policies. Organisational heads should be careful not to fall into this management trap.

Managing Employee Motivation

Competition in Incentive Appraisal Systems

Modern management and corporate practices require managers to reward their employees for positive job performance. Within the same paradigm, modern corporate practices require managers to identify talent and promote accountability among employees (based on their organisational performance).

However, the need to respect the above philosophy mirrors the principles of shrewd researchers, such as Allport (1954), who says the most effective way of eliminating stereotypes and discrimination is encouraging employee cooperation. However, the adherence to this principle undermines the concept of diversity.

For example, managers who prefer to improve organisational performance by encouraging competition among employees undermine the spirit of employee diversity. To support this view, Dipboye & Halverson (2004) argue, “Diversity and EEOC policies, that mandate tolerance, are undercut by programs such as rank and yank systems of performance appraisals that have the effect of pitting one employee against another” (p. 150).

Attaching rewards and pay increments to individual employee performance also creates the same effect. In fact, many researchers argue that organisational reward and appraisal systems play the most significant role in worsening employee discrimination (Dipboye & Halverson 2004).

Managers, therefore, need to be aware of the effects of adopting modern employee appraisal systems that promote individual employee performance because they may undermine the role of synergy in improving organisational productivity.

Relationship between Personal Self-fulfilment and Organisational Performance

The psychology of employee behaviour and organisational performance plays a significant role in understanding how to manage employee motivation. At the centre of this discussion is the ability of managers to understand how to use expert psychological knowledge to increase employee motivation levels.

This process starts by understanding employee desires and shaping them to create the perception that employee contribution, in organisational performance, is a step towards personal fulfilment. This strategy highlights the rise and the use of psychological knowledge (especially in the 20th century) by managers to manage employees (Rose 1990).

In detail, the use of psychological knowledge to influence employee behaviour stems from attempts by managers to manipulate employee thinking, and feelings, to align with organisational goals. As outlined in the human relations theory and neo-human relations theory, managers make employees to believe their personal accomplishments peg to organisational success (Jackson & Carter 2007).

With the realisation that coercive authority would not align with this strategy, managers adopt more subtle approaches of manipulating employee behaviours by inviting employees to connect their individual projects with organisational and institutional projects (Dipboye & Halverson 2004).

Indeed, managers are often under a lot of pressure to improve organisational performance by ensuring there is a perfect person-organisational fit (Willmott 1993). This pressure mainly exists in many industrial and organisational psychology studies (Dipboye & Halverson 2004).

Similarly, many organisational managers are under a lot of pressure to recruit, train, and retain employees that demonstrate adequate knowledge and skill in their jobs. Increased competition and the adoption of advanced technologies have further increased the pressure for managers to recruit the “right kind of workers” to propel organisation success.

This pressure limits their freedom to motivate, or employ, whomever they wish. This limitation often creates room for the introduction of discriminatory activities in an organisation. Dipboye & Halverson (2004) firmly believe that such opportunities for discrimination usually exist when organisations do not have a clear framework for employee appraisals.

This weakness also creates a lot of room for individual prejudice to dominate the process. Overall, managers make employees believe that their private accomplishments are unique to their self-fulfilment goals, but they are not. Although this is a managerial secret, organisational heads need to be aware of how to use it to harness employee potential and improve organisational productivity.

Managing Diversity

The main concept surrounding diversity management is the acknowledgement that today’s workforce comprises of different kinds of people. Although physical factors, such as age and sex, outline employee diversity models, unseen factors still define the success of employee diversity programs (Strachen & French 2010).

The common philosophy in diversity management is the understanding that harnessing employee differences may lead to improved organisational productivity. Here, increased productivity exists through a complete utilisation of talents and increased employee valuation.

Key issues that most managers need to understand when managing employee diversities are the influence of profit motives in the implementation of diversity programs, the failure to adopt a broader focus on diversity programs, and the existence of prejudice among employees.

Profitability over Ethics

Based on the doubts and cynicisms surrounding managerial efforts to uphold company visions and objectives, Jaffee (2001) says many people have expressed their doubts regarding managerial commitment to uphold employee diversity in the workplace.

For example, an analysis of the Australian workforce shows that although many Australian companies have applied diversity management programs, for more than three decades, widespread inequality exists (Habibis & Walter 2009). A deeper analysis of this situation shows that workplace practices have continued to reinforce traditional social inequalities that exist in the society (Habibis & Walter 2009).

Indeed, although managers reward exceptional employee performance, most employees still experience the same disadvantages that have characterised the Australian labour market for decades. For example, it is possible to predict a person’s labour market status by knowing his gender, racial identity, or even socioeconomic background.

The failure of company managers to uphold the principles of diversity management emerges from institutional failures that respect profitability, as opposed to ethics.

Certainly, instead of managers embracing diversity management, with the aim of reducing inequality, they use the concept to improve organisational profitability (as their main motivation) (Konrad 2003). Managers, therefore, use diversity management as a “business case” concept and fail to reduce inequality in this regard (Konrad 2003).

Narrow Focus on Diversity Management

Managers may fall into the pitfall of misunderstanding diversity management by adopting a narrow focus of the same. For example, instead of understanding group dynamics, a manager may be fixated on individual dynamics, thereby missing the point of diversity management (which aims to promote group cohesion/coordination) (Konrad 2003). The role of discrimination in undermining diversity management is at the centre of these discussions.

In the past, discrimination was prevalent in most organisations around the world. However, with the adoption of affirmative action, discrimination has significantly reduced. Moreover, with increased globalisation, many organisations have experienced working with people from different cultures.

Therefore, although discrimination may exist in some organisations, affirmative action has pushed it to the background of organisational practices.

Nonetheless, its existence and dynamics create the need for organisational managers to understand its effects, especially in supporting workforce diversity. Dipboye & Halverson (2004) say there is a thin line between improving organisational performance and embracing discrimination.

The main enabling factor for this flaw is the similarly narrow focus of business practices that construct diversity through a narrow focus of selfish interests. In other words, instead of adopting diversity management strategies, to increase employee comfort and profitability, some managers may adopt the same strategies, only if they believe they make business sense.

If they do not, they would not pursue these strategies. This narrow focus on diversity dilutes the impetus for adopting diversity management in conventional business practice.

To navigate the challenges of working with a highly diversified workforce, Waddell & Jones (2011) suggest that company managers should observe some fundamental principles of diversity management, such as securing managerial support and increasing diversity awareness.

Similarly, managers are encouraged to pay close attention to employee evaluation frameworks, encourage their employees to question discriminatory practices, and reward employees for supporting diversity objectives (among other factors) (Waddell & Jones 2011).

Managers should also understand that questioning the status-quo would destabilise existing power structures in the organisation. Therefore, they should be flexible and refrain from keeping some employees in specific positions (unnecessarily) because certain positions represent specific social cadres.

Conclusion

After weighing the findings of this paper, it is crucial to point out that the process of managing corporate culture, employee motivation, and workforce diversity is difficult and dynamic. Managers need to be aware of the several issues that affect employee behaviour and company performance (to strike a perfect balance between organisational productivity and employee satisfaction).

Notably, this paper emphasises the need to understand crucial issues that affect all aspects of governance, such as, how a narrow focus on diversity, public assertions of vision and corporate values, and the negligence of employee interests in profitability affect diversity management.

Similarly, this paper draws our attention to how the relationship between personal commitment, organisational performance, and competition in incentive appraisal systems affect employee motivation.

Lastly, this paper articulates the need for managers to consider the effects of societal cultures when managing corporate culture. Overall, these factors outline the primary considerations for managers as they steer corporate culture, workforce diversity, and employee motivation to support organisational productivity.

References

Ackroyd, S. & Crowdy, P. 1990, ‘Can Culture be Managed? Working with Raw materials: The Case of the English Slaughtermen’, Personnel Review, vol. 19. no. 5, pp. 3-12.

Allport, G. 1954, The Nature of Prejudice, Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts.

Dipboye, R. & Halverson, S. 2004, ‘Subtle (and Not So Subtle) Discrimination in Organizations’, in R Griffin & A O’Leary-Kelly (eds), The Dark Side of Organizational Behavior, Wiley, San Francisco, pp. 131-153.

Habibis, D. & Walter, M. 2009, Social Inequality in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

Jackson, N. & Carter, P. 2007, Rethinking Organisational Behaviour (2nd Edition), Prentice Hall, London.

Jaffee, D. 2001, Organization Theory: Tension and Change, McGraw Hill, Boston.

Konrad, A. 2003, ‘Special Issue Introduction: Defining The Domain Of Workplace Diversity Scholarship’, Group & Organization Management, vol. 28. no. 4, pp. 4-17.

Ogbonna, E. & Wilkinson, B. 2003, ‘The false promise of organizational culture change: a case study of middle managers in grocery retailing’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 40. no. 5, pp. 1151-1178.

Peters, T. & Waterman, R. 1982, In search of excellence: lessons from america’s best-run companies, Harper and Row, New York.

Rose, N. 1990, Governing the Soul: The shaping of the private self, Routledge, London.

Strachen, G. & French, E. 2010, Managing Diversity in Australia, McGraw Hill, Sydney.

Waddell, D. & Jones, G. 2011, Contemporary Management, McGraw Hill, Sydney.

Willmott, H. 1993, ‘Strength is ignorance, slavery is freedom: managing culture in modern organizations’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 30. no. 4, pp. 515-552.