Introduction

Hong Kong is one of the unique administrative regions of China that operates independently as a country since 1997, following the agreement between the region and mainland China to function as “one country, two systems” (Albert, 2019). The government of the People’s Republic of China granted the region autonomy for self-governance in all sectors except defence and foreign affairs. Consequently, Hong Kong has the freedom to carry out executive, judicial, and economic functions until 2047 (Chiu, 2018). The leader of the Hong Kong government is the Chief Executive, who can be impeached by the Legislative Council. The Chief Executive appoints the judges who serve in the Judiciary (Albert, 2019). Since gaining sovereignty, the country’s economy has grown tremendously, mainly due to its connection to the world’s second-largest economy. Hong Kong has become a global financial and shipping hub leading to its ascendancy to become the world’s second freest economy in the 2020 index (Focus Economics, 2020). Additionally, the GDP has grown steadily over the years, making the country one of the most attractive destinations for foreign investors.

Hong Kong’s Financial and Economic System

Between 1961 and 1997, when the country gained independence, its GDP grew by a factor of 180, while the per Capita GDP increased 87 times over the original value (Lee et al., 2019). The Coastal Metropolis is a primary conduit for goods getting into mainland China (more than 13% of all Chinese imports go through the ports in Hong Kong) (Chiu, 2018). In 1998, when the Hong Kong stock market was on the verge of collapsing, the government bought stocks worth more than US$ 15.3 billion to cushion its currency and to revive its ailing economy (Lee et al., 2019). Historically, the city-state has liberalized the private sector by giving the most important sectors of the economy a free hand. To date, the agriculture, services, and industrial sectors enjoy particular freedoms, which allow stakeholders in various industries to drive the economy of the metropolis. For instance, business start-ups in the country are allowed to operate without a license, regardless of the nature of their legal operations (Chiu, 2018). The only requirement for setting up a business in Hong Kong is to ensure that the business owner follows a simple business registration process.

Since gaining its sovereignty, Hong Kong has built a capitalist mixed service economy as well as the world’s best business environments. The firms operating in the metropolis pay low taxes, and there is minimal government intervention in the markets. Consequently, the country’s economy has grown to become the 35th largest economy globally, and its stock exchange is the 5th largest (Lee et al., 2019). As of December 2018, the country had a market capitalization of US$3.87 trillion, and the current Gross Domestic Product (PPP) is $480.5 billion (Focus Economics, 2020). The country’s GDP has been growing steadily for five years before the 2019 recession that occurred in the wake of political and social unrest in the metropolis. Government expenditure has formed 18% of the country’s GDP for the last three years, while budget surpluses have averaged 4% of the country’s output in the same period (Focus Economics, 2020).

One of the primary sources of government revenue is the trans-shipment of cargo through the city-state’s ports. The country was the 10th largest cross-border trading unit in 2017 in terms of imports and exports (Lee et al., 2019). More than 40% of the goods passing through its ports originate from PR China. The country’s role as a conduit for products in the state has made the region’s airport the busiest in the world in international cargo handling. However, the agriculture sector is not a significant contributor to the economy since there is minimal arable land in the metropolis. This sector contributes a paltry 0.1% of the GDP since most of the farmers focus on growing flowers (Lee et al., 2019). Consequently, almost all of the food consumed in the country is imported from other countries.

Hong Kong’s Political System

The city-state’s administration consists of three main arms of government, the executive, the judiciary, and the legislative council. After the “one country, two systems” agreement of 1997, the country adopted the Basic Law of Hong Kong as the regional constitution (Albert, 2019). The Chief Executive is the leader of the unique administrative region and can serve in that capacity for a maximum of two five-year terms. Hong Kong’s head of government has to win a nomination process that involves an election whose voters are 1,200 local and government leaders (Albert, 2019). However, he/she can only assume office after being appointed by the state council and the Premier of China.

The executive has the mandate of enacting and enforcing the law in the region, and its head is responsible for appointing the executive council members. The chief executive has the authority to dissolve the legislative council and to enact regulations that would restore peace in emergencies. On the other hand, the legislative assembly has the power to enact laws, to approve the budget, and to impeach the leader of the country. Each of the 70 members of the council serves on the board for four years after being elected from either a geographical or a functional constituency (Albert, 2019). The judiciary comprises of the lower courts, which are answerable to the Court of Final Appeal. The region’s leader appoints all the judges who serve in the Hong Kong judiciary.

The two functions that were not granted to Hong Kong in the 1997 agreement are the defense and the foreign affairs dockets. The Hong Kong garrison is tasked with protecting the public from external threats, but it is comprised entirely of soldiers from mainland China (Albert, 2019). The military has no provisions for Hong Kong residents to enlist in the army. China’s ministry of foreign affairs handles the region’s foreign affairs. However, the city-state retains the power to foster independent cultural and economic relations with other countries.

Hong Kong’s Economic Stability

In the last quarter of 2019, even before the outbreak of the Corona Virus global pandemic halted many operations in the metropolis, the region’s economic activity plummeted faster than any other time in over a decade (Focus Economics, 2020). Fixed investments in the area and household consumption both declined in 2019, chiefly due to the political standoff between the protestors and the Hong Kong administration. The protestors consider Beijing’s tightening grip on the region’s political activities as a threat to the city-state’s sovereignty (Focus Economics 2020). Economic analysts have projected a recovery due to Beijing’s reluctance to intervene in the protests after the impact of the airborne coronavirus halted the riots.

Since the beginning of this year, various metrics prove that the economy of the region is ailing. The purchasing managers’ index went (PMI) up to 34.9 from 33.1 in the previous month (Focus Economics, 2020). This downturn indicates that the business environment of Hong Kong’s private sector is continually deteriorating. Many businesses in the region have declined in new orders, and the employment levels have reduced the PMI index of the 1st quarter implies that the city-state’s economy has fallen deeper into recession.

Similarly, February’s retail sales volume has declined by 46.7% of the sizes posted in 2019 (Focus Economics, 2020). Consumer confidence has fallen, and there have been virtually no tourist arrivals due to the coronavirus outbreak. When the average volume of retail sales is adjusted from December 2019 to February this year, the statistics show an 11.7% decline (Focus Economics, 2020). Further, the retail sales are expected to plunge even further, but economic analysts predict a recovery once the government reopens its borders.

Generally, the region’s economy is undergoing a recession, but the trend is expected to reverse and return to normal once the country’s borders have been reopened. The political unrest and the tension between Hong Kong and Beijing are expected to subside, considering that there are no more protests due to the fear of contracting the deadly Corona Virus (Focus Economics, 2020). Additionally, the global pandemic has seen the city-state’s government close its borders to tourists to avoid a health crisis. However, once the situation normalizes, many expect the country to regain its appeal to investors.

Hong Kong’s Trade Relationship with America

Currently, there is a healthy trading partnership between the United States and Hong Kong. In 2018, America was the 2nd most significant trading partner of the Asian city-state as bilateral trade increased by 8.1% in the same year (Chiu, 2018). In that year, the state of Hong Kong was the United State’s 42nd most crucial source of imports. Also, Hong Kong is the country with which the world’s largest economy enjoys the most prominent trade surplus (which amounts to over US$31 billion) (Lee et al., 2019). Additionally, US nationals are one of the most prevalent foreign presences in the state as there were close to 21,000 of them residing in the metropolis in 2018, and the number of US visitors stood at 1.3 million that year. Not only are there more than 60 large US companies that are represented in Hong Kong, but also there were 290 regional headquarters of American multinationals in Hong Kong in 2018 (Chiu, 2018). Moreover, the metropolis is an essential nexus for merchandise trade between the world’s two largest economies. Finally, Hong Kong does not violate foreign companies’ intellectual property rights and protects all workers through international labor legislation.

Currency Exchange Rates

The exchange rate between the currencies of the two countries has remained relatively constant in recent years, with one US dollar fetching 7.75116 Hong Kong dollars. In other words, one HKD is worth 0.129013 USD (Chiu, 2018). The constant rates indicate a healthy trading relationship between the two countries.

Risks of Investing in Hong Kong

Despite an otherwise excellent business environment, there are a few risks associated with investing in the metropolis. The main ones include:

- The current geopolitical issue is affecting normal business operations, and the situation is likely to be a persistent problem due to the country’s proximity to China (Lee et al., 2019).

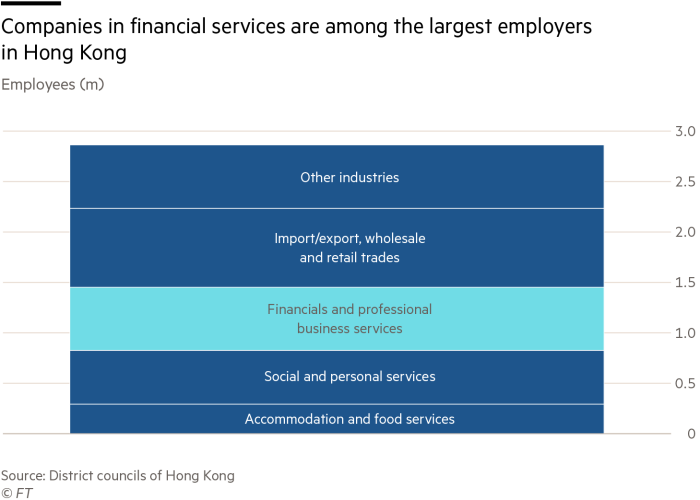

- Hong Kong’s economy is excessively reliant on the financial sector, which would pose a problem during periods of economic downturns (Chiu, 2018).

- The rent for properties and offices is high.

- The workers in the metropolis demand significantly high wages than employees in the neighboring countries.

Comparative Advantage of Investing in Hong Kong

Some of the comparative advantages that the area holds over other countries include free trade policies and favourable tax measures. Further, its position as the gateway to the most significant production base in the world (China), economic stability, an adequate infrastructure, and one of the world’s best financial systems (Focus Economics, 2020). Additionally, international labor laws protect the workers in the country, and foreign companies’ intellectual property rights are protected.

Viability of Investments in Hong Kong

While investing in Hong Kong today would result in massive losses for investors, it is hardly a good time to spend anywhere else in the world due to the global corona pandemic. However, the ongoing political unrest is a legitimate source of concern. On the other hand, setting up a business in the coastal metropolis will be a desirable proposition after the effects of the corona pandemic have subsided. The region’s government has proven in the past that it will take all the necessary actions to stabilize its economy and to attract foreign investors. Currently, the metropolis is home to more than 7.5 million people, most of whom are Han Chinese (Albert, 2019). The state has a residential population density of close to 100,000 people per square kilometre (Chiu, 2018). Whereas Cantonese is the first language, more than half of the inhabitants can speak English. Both factors are a huge boost for American investors since their businesses will have plenty of customers, half of whom can speak English.

Additionally, due to the highly effective transport and utility infrastructure present in the area, investors should not worry about moving their merchandise into, across, and out of the metropolis. According to recent statistics, more than 90% of daily commuting occurs via public transport, which eases congestion in central business districts (Chiu, 2018). Additionally, the locals use smart, contactless cards on their way to and from work on buses, trains, ferries, and other means of transport. Also, most of the energy is generated locally, and more than 92% of the households are connected to broadband internet (Lee et al., 2019). The main challenge facing the local population is access to safe drinking water.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Despite considerable political unrest in Hong Kong in recent months, as well as the coronavirus pandemic, the unique administration region of China is still one of the best investment locations in the world. The metropolis has shown considerable resilience in the wake of these recent setbacks. The country has a robust banking system capable of weathering this recession, which will restore the waning consumer and investor confidence.

The bedrock of the economy is the services sector, and investors should focus on the provision of privatized services in education, health (especially assistance to the elderly and the disabled), tourism, and technologies that will conserve the environment. The services sector employs the bulk of the local population, implying that labor will be readily available.

To sum up, despite the current turbulent economic times, all the pointers indicate that the country’s economy will recover, and investors from the United States should take advantage of the excellent trading relationship between the two countries. Not only is it easy to run a business in the metropolis, but American investors will have access to the Chinese production base. In that way, they will not worry about their intellectual property rights being violated.

References

Albert, E. (2019). Democracy in Hong Kong. Council on Foreign Relations. Web.

Chiu, S. W. K. (2018). City states in the global economy: Industrial restructuring in Hong Kong and Singapore. Routledge.

Focus Economics. (2020) Hong Kong economy – GDP, inflation, CPI and interest rate. Web.

Lee, F., Tang, G., & Tsang, C. K. (2019). Financialization and generational differences in the correlates of perceived importance of investment in Hong Kong. Social Transformations in Chinese Societies, 15(2), 161-177.