The COVID-19 outbreak has brought the entire world to a standstill in a matter of mere months. The new virus has negatively affected the major economic sectors. Those of them that rely on travel and gatherings of people such as tourism are arguably hurt the most. Tourism felt the ramifications of the looming pandemic even before the World Health Organization (WHO) gave the outbreak that status.

Customers were growing concerned, fearful, and discouraged from traveling, hearing the news, and learning about the speed with which the virus was swaying the planet. Once the WHO announced the pandemic, country governments proceeded with putting legal hurdles to travel, further straining the tourism sector. Healing and recovering the tourism industry now largely relies on its ability to evaluate and implement risk reduction strategies. This paper argues that the existing approaches toward risk reduction might not work amid the COVID-19 pandemic or at least, will be severely challenged by the unprecedented nature of the current events.

The State of the Tourism Industry During the Pandemic

Since the very onset of the outbreak, the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization has been communicating that alongside the transport sector, the tourism sector will be one of the most affected. Tourism is a sector that largely relies on person-to-person interactions, which makes it vulnerable when it comes to crises that go beyond the borders of one country. So far, the COVID outbreak has caused lockdowns of entire cities and countries and travel restrictions at the national level. The sector has been halted starting from the largest players employing thousands of workers to small independent businesses with just a staff of just a few people.

Before the crisis, tourism has maintained the livelihood of not only people directly employed by the sector but also their families and third-party suppliers. Besides, tourism has long been a source of income for many vulnerable social groups such as women and youth in developing countries. The industries that are closely related to tourism such as agriculture, construction, food retail, and finance are also suffering from the consequences of the virus spread.

Prior to COVID-19 outbreak, tourism statistics were indicative of a steady growth and optimistic future prospects even though the previous financial crisis was just twelve years ago. The United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (2020) reports that between 2010 and 2018, global employment across all economic sectors had increased by 11%. The tourism sector, on the other hand, had enjoyed a spurt of growth as big as 35%. By 2019, the sector had come to represent one-third of the world’s exports of services whose revenue had amounted to a whopping US$1.5 trillion. In developing countries, the share was even larger: 45% of the total export of services.

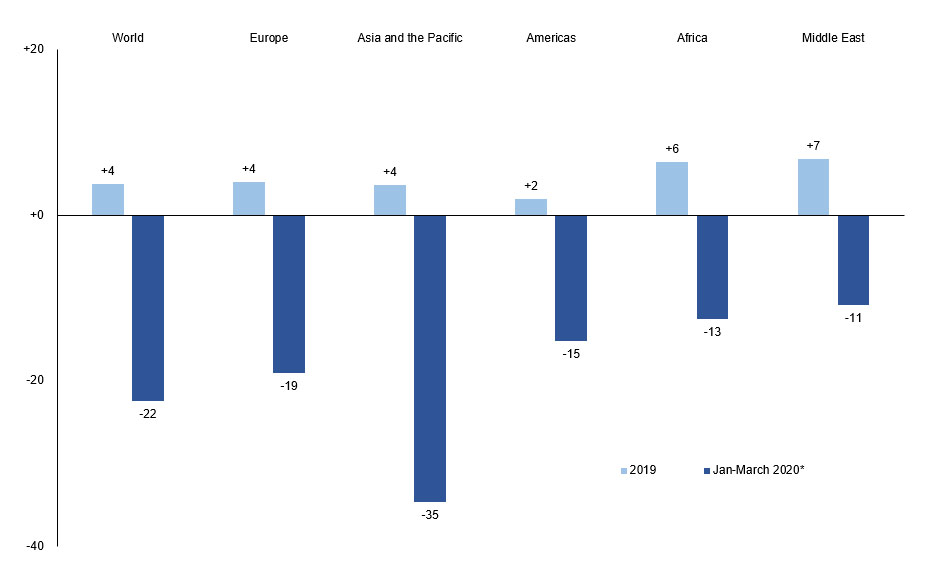

To say that the COVID-19 outbreak has had a negative impact on the tourism industry would be an understatement. As seen from Graph 1, the first quartile of 2020 saw a 22% decline in the number of tourist arrivals whereas a year ago there was a 4% decrease (The World Tourism Organization, 2020). Graph 1 shows that Asia and the Pacific where the pandemic started have been hit the hardest: the region is experiencing a 35% decline (The World Tourism Organization, 2020). Europe where many countries’ economies rely on tourism is suffering from almost a 20% drop in the number of tourist arrivals (The World Tourism Organization, 2020). These estimations translate into a loss of 70 million international arrivals and about US$80 billion in receipts. What is concerning is that the pandemic might have not peaked yet, meaning that the numbers might still soar, aggravating the state of the industry further.

On average, the United Nations’ United Nations’ World Tourism Organization is translating the ongoing and future adverse changes in the global tourist industry into a loss of 850 million to 1.1 billion international tourists. This, in turn, might suggest a loss of US$910 billion to US$1.2 trillion in export revenues from tourism. The COVID-19 crisis is also likely to wreak havoc on employment in the sector: today, it is estimated that 100 to 120 million direct tourism jobs are at risk.

In response to the pandemic, the UNWTO has pledged to cooperate closely with the World Health Organization (WHO) that is the lead UN agency managing the outbreak. The UNWTO seeks to ensure that the health measures proposed by the WHO are introduced in ways that mitigate the negative impact on international travel and trade. The UNWTO expresses its solidarity with affected countries and highlights the tourism sector’s proven resilience that has helped it withstand other natural and anthropogenic disasters. The agency is committed to help the industry heal and recover, but the question still stands as to how it could be possible during a time like this.

Existing Frameworks Toward Risk Reduction

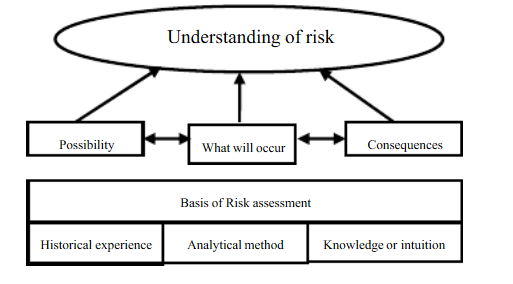

Tourism crises are regularly precipitated by natural and anthropogenic disasters such as hurricanes, floods, pandemics, terrorist attacks and many others. Over the last few decades, the tourist industry has adopted and developed several risk reduction and disaster management frameworks (The United Nations ESCAP, 2020). Ye and Wen (2016) provide a formulaic expression of disaster risk (see Image 1). Image 2 displays the basic elements of understanding risk: first, it is essential to assess the very possibility of an adverse event happening. Second, if the possibility is tangible, what will occur needs to be specified in concrete terms. The third step of understanding risk is outlining the consequences. Risk assessment relies on three pillars: historical experience, analytical methods and knowledge or intuition. As seen from Image 2, risk assessment mostly deals with backwards-looking data: it analyzes data collected in the past to gain insights about what is about to happen this time.

Ye and Wen (2016) highlight the difficulty of risk assessment for the tourist industry before a disaster happens. The researchers compare disaster risk management and disaster management and claim that the former presents far more challenges than the latter. Disaster management deals directly with the consequences of adverse events. For instance, Ghaderi, Mat Som and Henderson (2015) write that the 2011 Thailand floods led to breaches in infrastructure. Bangkok’s Don Muang airport was engulfed in torrents and did not reopen until March next year. The city’s major highways were flooded, destroyed, or submerged underwater (Ghaderi, Mat Som & Henderson, 2015). The country had to allocate emergency funding on spot, which was difficult because there was not enough budgeting done before the event of disaster (Ghaderi, Mat Som & Henderson, 2015). Using this example, it becomes apparent that post-factum assessment is easier than factoring in all the risks and calculating the possibilities beforehand.

In 2015, the United Nations introduced the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction in which it outlined four key priorities and seven goals to achieve by 2030. The priorities are as follows: 1) understanding disaster risk; 2) improving disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk; 3) investing in disaster reduction for building up resilience; 4) enhance disaster preparedness for effective response (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2015). As seen from the list of priorities, the United Nations takes a proactive stance toward managing disasters and emphasises preparation as opposed to handling consequences (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2015).

In relation to the outlined priorities, the global institution developed seven goals that are grouped into two categories – “reduce” and “increase.” In accordance with the Sendai framework, by 2030, there needs to be a reduction in mortality, economic loss, the number of affected people and damage to critical infrastructure. On the contrary, it is imperative to increase the number of countries with local disaster risk reduction strategies. There also needs to be an increase in international cooperation as well as availability to warning systems and information regarding disasters.

In view of all these challenges, it might make sense to take a look at what the World Tourism Organization that oversees the situation has to contribute to the discussion. At present, in its official document titled “Supporting Jobs and Economies Through Travel and Tourism, ” the WTO proposes three feasible solutions: 1) managing the crisis and mitigating the impact; 2) providing stimulus and accelerating recovery; 3) preparing for the future. Managing the crisis encompasses measures such as incentives to job retention and help for self-employed and entrepreneurs. Preventing even bigger losses will require support for companies’ liquidity as well as review of review taxes, charges, levies and regulations impacting transport and tourism. As for reviving the sector, the WTO sees a lot of use in providing financial stimulus for tourism investment and operations.

Challenges of Evaluating and Implementing Risk Reduction Strategies

Today, it has become clear that the COVID-19 outbreak compromises the applicability of the existing risk reduction frameworks. As noted by Deloitte (2020), the pandemic has already changed the world’s “collective calculus of uncertainty” simply because there have been no similar precedents in living memory. Surely, at some point, the global economy had to withstand Black Monday and the 2007 financial crisis. Apart from that, natural and anthropogenic disasters such as Chernobyl, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina took a toll on economic activities (Deloitte, 2020). However, what differentiates the current COVID-19 outbreak even from a seemingly similar pandemic is how global in scope this public health threat has come to be.

Baker, Bloom, Davis and Terry (2020) point out that probably, the closest parallel that could be drawn right now is with the Spanish Flu pandemic a century ago. However, the Spanish flu outbreak provides a valid point of comparison only in terms of mortality. Baker et al. (2020) explain that the context of the Spanish Flu pandemic was vastly different in terms of economy and politics. As compared to one century ago, the world has become much more interconnected due to migration and advances in technology. For this reason, the current situation requires a different scale of containment and mitigation policies as well as risk reduction strategies in sectors such as tourism.

Aside from the unprecedented nature of the pandemic, the second challenge of risk reduction implementation is the speed with which the COVID-19 crisis is swaying the world markets and all the industries involved. Baker et al. (2020) provide concerning numbers, using the United States as an example. In February 2020 when the virus was a distant threat affecting primarily East Asia, the North American country enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate in the past seven decades at 3.5% (Baker et al., 2020). By the end of March, more than ten million Americans had filed for unemployment benefits.

However even this figure might not be not exactly precise: most likely, even more Americans have lost their jobs but did not proceed with applications. This suddenness impedes the application of methods that are based on backwards-looking statistical analyses and historic data included in the framework by Ye and Wen (2016). It is now argued that forward-looking statistical analyses are critical to relieving the COVID-19 crisis. Baker et al. (2020) write that such forward-looking measures as stock-market volatility, newspaper-based measures and business expectation surveys may be helpful with understanding of the risk.

In relation to the tourist industry, the latter measure is of a special interest. Essentially, what Baker et al. (2020) are proposing is to request predictions from firms in a particular sector (example: tourism) with regard to their expected losses and changes in other deliverables. Based on these data, financial and business institutions would be able to calculate the averages and make projections.

However, this method of risk evaluation comes with its own set of challenges. Travel agencies might not be the experts in predictions, primarily because they lack adequate historical data to ground their observations in. As Sheetz (2017) reports, the average large business longevity has shrunk to under twenty years while for small and medium business the figures are one-digit. Moreover, according to the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization, the last time the tourism sector was this much on a decline was in the 1950s. These statistics suggest that many travel agencies have not probably been around long enough to have experience with dealing with global health threats and other disasters.As a result, they cannot have enough insight into the subject matter and properly evaluate risks.

As for assessing consequences as a part of risk understanding as proposed by Ye and Wen (2016), the COVID-19 outbreak has one too many scenarios to make any generalizations. The United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (2020) has so far put forward three possible scenarios: from the most to least optimist:

- Scenario I implies that there will be a gradual opening of international borders and easing of travel restrictions by the beginning of July. In this case, the loss in the number of international tourist arrivals will be 58%;

- Scenario II is based on the gradual opening of international borders and easing of travel restrictions by the beginning of September. In this case, the loss in the number of international tourist arrivals will be 70%;

- Scenario III is based on the gradual opening of international borders and easing of travel restrictions by the beginning of December. In this case, the loss in the number of international tourist arrivals will be 80% (The United Nations’ World Tourism Organization, 2020).

It is readily imaginable that risk mitigation measures for the tourism industry in each individual case would be drastically different. Moreover, the WTO warns that the prospects for 2020 have been downgraded several times since the onset of the outbreak, which is why the available scenarios may still not reduce the uncertainty. The situation is aggravated by the soaring unemployment rate: as Temko (2020) reports, half of the world’s working population, or 1.6 billion people, is now at risk. Admittedly, people pushed to the brink of poverty will cut their non-essential expenses such as travelling and prioritise meeting their most basic needs such as food, shelter and health. Alternatively, those who will be ready to travel might suffer from ever-shrinking choices and decreased quality of service as the tourism industry is projected to lose hundreds of thousands of employees across the globe.

The Sendai framework also proved to be not exactly applicable to the COVID-19 outbreak and its impact on the tourism industry. The plan to transform the way countries approach disaster risk reduction had to be realised over the course of 15 years with the deliverables to be assessed in 2030 (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2015). However, the COVID-19 crisis occurred only five years after the framework was introduced, meaning that many countries were still in the beginning stages of preparation. Now, countries and regions vary significantly in their degree of readiness to respond to the crisis. This effect of this unevenness is not confined to specific countries that lack resources. In actuality, it means that these countries may become the new epicentres of disaster and have a negative impact on neighboring regions. Therefore, a part of the uncertainty can be attributed to the need to make a group effort in combating the virus, which is impeded by some countries’ poor preparedness. Under these conditions, the tourism industry might have even less visibility on the progress and setbacks and even less clarity regarding its future prospects.

Another aspect mentioned in the Sendai framework whose applicability might be compromised is recovery as one of the four priorities. The Sendai framework shows that “going back to normal” should be the logical result of building up resilience and strengthening governance in the face of disaster. However, as some analytics such as Khan (2020) point out, the travel industry might change forever. Khan (2020) theorises that most likely, even after significant relief, airline companies and hotels will have to not only maintain sanitation guidelines but also invest into technology such as robot cleaners. Businesses will have to figure out how to provide customers with personal space that they feel that they have control over (Khan, 2020). It is readily imaginable how the need to take drastic measures can further strain the budget of many businesses that are already barely capable of staying afloat.

As for the framework developed by the WTO, the organization acknowledges that the proposed measures are just generalizations. In actuality, the COVID-19 varies in the degree of impact it has on different countries as well as the magnitude of disaster it has caused in different regions. For this reason, the ability of countries and their respective tourism sectors to respond to this unprecedented crisis will also show a significant variation. Factors such as differences in infrastructure, human resources, economic capacity or political factors will shape the future of the tourism industry in each country.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 global pandemic is an unprecedented disaster even that has had a profound effect on all major economic sectors. The tourism industry has proven to be among those that have suffered from the greatest losses due to the spread of the virus. Today, it is estimated that by the end of the year, the decline in the number of international tourist arrivals is likely to be between 60% and 80%. Over the last few decades, the tourism industry has proven its resilience in the face of natural and anthropogenic disasters. There are several frameworks and approaches to understanding and preventing risk as well as managing disaster events. However, it seems that the COVID-19 global outbreak might compromise the applicability of many of them due to its suddenness and the speed of eruption. The tourism industry is suffering from uncertainty: there are multiple scenarios as to how the situation will unfold. Besides, there are concerns that there is no going back to “normal” as the COVID-19 outbreak will dictate new norms even after significant relief.

Reference List

- Aitsi-Selmi, A, Egawa, S, Sasaki, H, Wannous, C & Murray, V 2015, ‘The Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction: renewing the global commitment to people’s resilience, health, and well-being’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 164-176.

- Baker, SR, Bloom, N, Davis, SJ and Terry, SJ 2020, Covid-induced economic uncertainty 2020. Web.

- Deloitte 2020, COVID-19: confronting uncertainty through & beyond the crisis, 2020. Web.

- Ghaderi, Z., Mat Som, A.P. and Henderson, J.C., 2015. When disaster strikes: The Thai floods of 2011 and tourism industry response and resilience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(4), pp.399-415.

- Khan, S 2020, ‘The era of peak travel is over’, Vice, 2020. Web.

- Sheetz, M 2017, ‘Technology killing off corporate America: Average life span of companies under 20 years’, CNBC, 2020.Web.

- Temko, N 2020, ‘No jobs, so what future? Half the world’s workforce on the edge’, The Christian Science Monitor, 2020.Web.

- The United Nations ESCAP 2020, The future of tourism post-COVID-19, 2020. Web.

- The United Nations World Tourism Organization 2020a, COVID-19 response, 2020. Web.

- The United Nations World Tourism Organization 2020b, International tourist numbers could fall 60-80% in 2020, 2020. Web.

- The United Nations World Tourism Organization 2020c, Supporting jobs and economies through travel & tourism, 2020. Web.

- Ye, X and Wen, J 2016, ‘Study on disaster risk management framework in tourist destination’, Environmental Science and Information Application Technology, vol. 3, pp. 182-186.