Abstract

Cyclic voltammetry is a part of potentiodynamic experimental methods. Computer controlled experimental equipments are developed day by day with development of automated data collection and mathematical description of potentiodynamic curves are also developed day by day. In now days the users are able to obtain the basic characteristics of the studied system regarding mainly a mechanism of electrode reactions and their kinetic parameters with the help of these techniques.

Electrolysis, cyclic voltammetry, amperometry and several other techniques are the example of this and they might be described as “active” electrochemical methods because the experimenter drives an electrochemical reaction by incorporating the chemistry into a circuit and then controlling the reaction by circuit parameters such as voltage. A cyclic voltammetry (CV), measures the current response of a solution over a range of applied potential

Introduction

Cyclic voltammetry is an attractive method for teaching a number of concepts in electrochemistry. The principles of cyclic voltammetry are introduced to qualitatively examine the oxidation and reduction of the ferricyanide ion which is a simple, reversible, diffusion-controlled electron transfer reaction. The cyclic voltammetry data can also be used to quantitatively calculate the diffusion rate of the ferricyanide ion. Finally, cyclic voltammetry will be used to study the electrochemical characteristics of thyronine and the chemical reactions that occur following its oxidation. Cyclic voltammetry is described by smooth increase of a working electrode potential from one potential limit to the other and back.

The potential limits and the potential sweep rate are the basic adjustable parameters in this. Properties of an electrolyte like the concentration of electro active species and temperature could also be affected.

Discussion

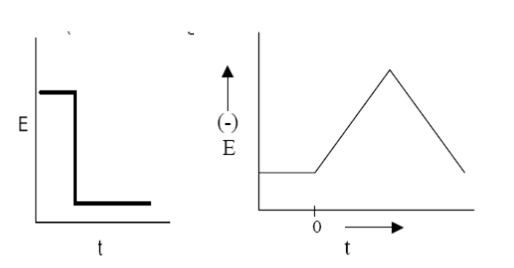

In typical cyclic voltammetry, a solution component is electrolyzed (oxidized or reduced) by placing the solution in contact with an electrode surface, and then making that surface sufficiently positive or negative in voltage to force electron transfer. In CV the potential of the working electrode is swept across a potential range at a constant rate while measuring the resulting current. In simple cases, the surface is started at a particular voltage with respect to a reference half-cell, the electrode voltage is changed to a higher or lower voltage at a linear rate, and finally, the voltage is changed back to the original value at the same linear rate.

The potential is measured between the reference electrode and the working electrode and the current is measured between the working electrode and the counter electrode. The three-electrode method is the most widely used because the electrical potential of reference does not change easily during the measurement. Three electrodes will be used: working, reference, and auxiliary. A good working electrode must be relatively unreactive. It must also be polarizable. When the surface becomes sufficiently negative or positive, a solution species may gain electrons from the surface or transfer electrons to the surface. This results in a measurable current in the electrode circuitry.

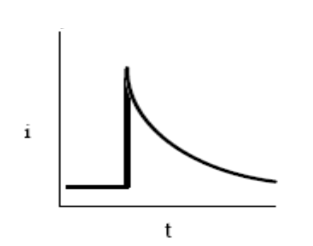

However, if the solution is not mixed, the concentration of transferring species near the surface drops, and the electrolysis current then falls off. When the voltage cycle is reversed, it is often the case that electron transfer between electrode and chemical species will also be reversed, leading to an “inverse” current peak.

The response of the system is shown by a curve called polarisation curve. this curve shows the dependency of current flowing through an electrode on its potential. This curve is sometimes also known as an electrochemical spectrum of the studied system.

Generally there are two limiting cases of studied systems do exist. It is a reversible electrode process and then an irreversible electrode process. As the potential is applied, the concentration of the oxidized species is depleted at the surface. This lower concentration at the surface gives a higher concentration gradient (at least initially) so according to Fick’s law of diffusion equation, we will have more flux to the surface and hence a higher cathodic current.

As we continue to make the potential more negative, the concentration of the oxidized species at the surface will eventually go to zero. Simultaneously, the volume in the solution that is depleted of the oxidized species will increase and the concentration gradient will begin to decrease. As the concentration gradient decreases, we will have less flux to the surface and current will begin to decrease. All of this will result in a current-voltage curve.

One current peak on the potentiodynamic polarisation curve corresponds to every electrode reaction. If the equilibrium potentials of these reactions are close to each other the peaks corresponding to these reactions could overlap. Each peak is characterised by several basic data. These are given in Figure. It is: potential (Ep) and current (Ip) of the peak, a half-wave potential (E1/2 when I=Id/2) and a potential at the half of the peak (Ep/2 when I=Ip/2). The way of reading the current density of a peak is shown in Figure.

The concentrations can be described by the Nernst equation-

Where E is the applied potential and E0’ is the formal electrode potential.

The last aspect of CV that we will discuss is its ability to provide information about the chemistry of redox couples. This is perhaps the most attractive feature of this technique. For example, if a redox couple undergoes two sequential electron-transfer reactions, you will see two peaks in the voltammogram. If either the reduced or oxidized species is unstable, you might see a voltammogram such as that shown in Figure. Such qualitative information is very useful.

Cyclic voltammetry requires two simple operational amplifier (op amp) circuits.

Conclusion

A discussion of electrochemical concepts and chemical applications may be found for cyclic voltammetry in standard analytical chemistry texts. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is considered to be the versatile electroanalytical technique currently available. It is generally the first experiment to be run when dealing with any electrochemically active species. The basic theory behind CV is to measure the current response at an electrode surface to a specific range of potentials in an unstirred solution.

References

Dennis H. Evans, Kathleen M. O’Connell, Ralph , “Cyclic Voltammetry”. Web.

“Cyclic Voltammetry”. Web.

Laura A. Langley, “Study of Electrode Mechanism by Cyclic Voltammetry”. Web.

pcogren, “Cyclic Voltammetry”. Web.