Organizing an exhibition of art or other artifacts by selecting artworks to be introduced, arranging where and how they will be presented, and presenting a shared vision is what constitutes curation. The goal of curation is to discover and conserve what is significant before sharing that information with society. Curating an art exhibition entails conveying a story, addressing an issue and its requirements, and investigating material culture. In the present paper, the curated collection under discussion is “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art” in the context of Asian art history narratives. The presentation was made available online on Asianart.com on September 05, 2019, for a global audience interested in Asian culture. It was curated by the staff of the Kruizenga Art Museum, who have made the Tantric Buddhist religious life in Mongolia the center of the exhibition (Asianart.com., n.d.). The display contains several artworks chosen from the museum’s more extensive catalogue. Most artworks are from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as Tantric Buddhists flourished in Mongolia. The exhibition reveals the multifacetedness of Mongolian religious beliefs as a part of Asian identity expressed in an artistic form.

Unfortunately, Western exhibitors rarely touch on the topic of unique Mongolian art and spiritual life for several reasons. Namely, for most of the previous century’s second half and the recent decades, Mongolia was seen through the prism of modernism, which focused on the works created under Soviet rule. In turn, the USSR’s repressive control of the artworks made and published demanded that it is within the limits of Soviet realism (Uranchimeg 2020). Furthermore, the USSR’s government prosecuted religiously-affiliated people and banned any religious expression in art as well. Most Buddhist temples in the country were destroyed, except for the nomadic ones, with much less material culture stored in one place and thus less susceptible to destruction (Uranchimeg 2020). As a result, the cultural exchange between Mongolia and Western museum-visiting communities is a recent phenomenon, which makes the audience less educated about Mongolian artistic, cultural, and religious heterogeneity. Moreover, the museums might be less influenced by the presence of established perception of tradition in this part of Asian art.

However, Tantric Buddhism was a prominent religious phenomenon, which is demonstrated by the devotional desire to create lavish and complicated artworks. For example, “Vajrabhairava with Three Forms of Yama Dharmaraja” in Figure 1 contains precious pigments, gold, and silver while conveying an intricate composition with detailed depictions of deities (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 87). Tantric Buddhism, also known as Vajrayana Buddhism, is a branch of Buddhism that employs holy incantations, hidden gestures, advanced meditation, visualization methods, and complicated devotional rituals to aid devotees in their quest for spiritual enlightenment (Asianart.com, n.d). Art is crucial in Tantric Buddhist rituals because it helps believers picture the gods they are summoning and provides a tangible connection to those deities. Moreover, art pieces are utilized to teach crucial parts of Tantric Buddhist theory and history. Furthermore, they may serve as talismans to protect or deliver favorable fortune to their possessor.

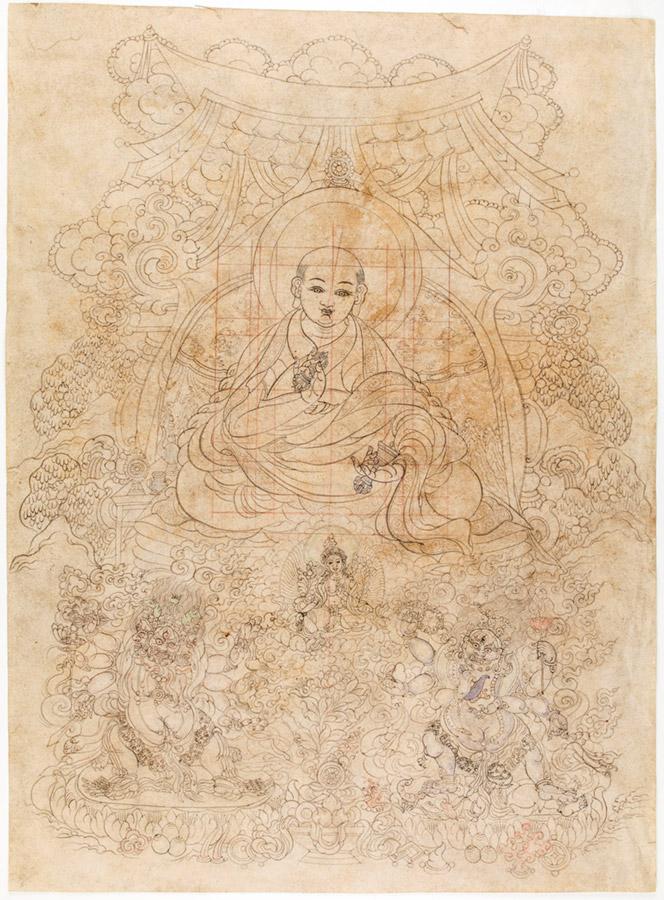

The exhibition offers a unique viewpoint on Mongolia, emphasizing the uniqueness of Mongolian religious traditions and aesthetic practices via material culture. Material culture consists of artistic and ethnic artifacts that express cultural identity, as well as information that provides knowledge about all of the features that determine the culture’s uniqueness (Lopes 2014, 238). Hence, festivals, rural celebrations, traditional customs related to popular deities, and Tantric Buddhist deities are enlivened by various types of artwork in the exhibitions. As such, the online display contains paintings, such as “Padmasambhava Surrounded by Meditational Deities” in Figure 2 (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 173). Padmasambhava was a semi-legendary person who is credited with bringing Tantric Buddhism from India to Tibet (Asianart.com, n.d). A five-syllable blessing phrase is written on the back of the picture, which is typical for the paintings in the collection. Moreover, the exhibition presented an unfinished drawing, where the artist applied the grid lines that covered the face and body of a saint to guarantee proper proportions in Figure 3 (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 173). The curators ensured that there is diversity of style and depicted deities in the paintings.

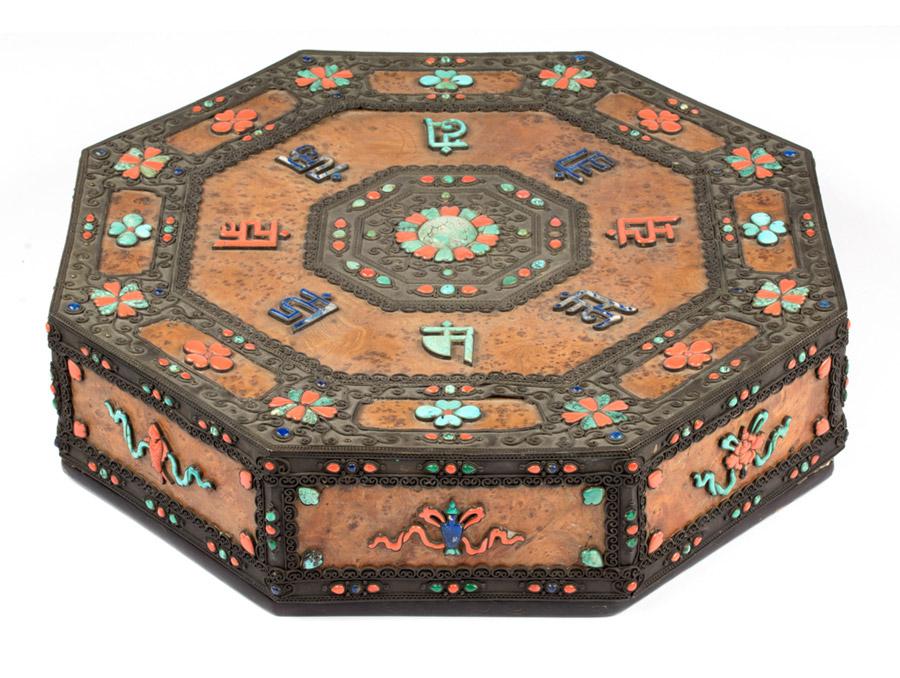

The other notable pieces in the exhibition demonstrate the wide variety of the types of religion-related material culture in Mongolia. For example, there is a bronze statuette in Figure 4 with a deity riding a camel, which was a common transportation method in the 19th century (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 144). Next, “Lords of the Cemetery” in Figure 5 is a wooden papier maché (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 121). In tantric ceremonies, these spirits are called to defend people from criminals and bring monetary riches (Asianart.com, n.d). Finally, the exhibition displays a box from burlwood, bronze, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and coral, which was probably used to present a statuette (Mason, Near, and Wagner 2019, 208). Although these are not all the material objects from “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art” online exhibitions, the overview demonstrates that the curators attempted to show different types of art used in ceremonies and rituals.

Furthermore, it is essential to discuss the museum’s participation in creating a nonstereotypical picture of Mongolia via curatorial practice, as well as its function in developing an identity of Mongolia. According to Lopes (2014, 243), the presentation of cultures necessitates an incredible understanding of the cultural background, in which religious beliefs, aesthetics, and creative traditions all play essential roles in constructing cultural identity. The curator’s task is to strike a balance between item material conservation and immaterial heritage preservation. In the exhibition under discussion, the protection of material objects is achieved through the digital nature of the display. Moreover, the curators provided descriptions for each artwork, clarifying the deities depicted or the use of the objects. However, it could be argued that the exhibition still lacks context in its online format. Namely, there is no grouping of the objects by some criteria (such as a period or theme), which disorients an observer. Moreover, the design of the display is minimal, although it would be valuable to demonstrate the relationship between the artworks. As a result, the works appear unorganized, without their original sacral contexts and uses.

The other visible issue with the exhibition is the use of standardized iconography applied to the paintings. According to Abe (2012), “recourse to a standardized iconography is often inadequate for the purpose of identification, given that strategies of standardization are usually a much later development and a retrospective imposition” (99). The author claims that it is more important to underline the localizations of culture by highlighting distinctive artistic expressions than convey only encyclopedic knowledge of pan-Asian beliefs. As a result, the exhibition seems to be more of an ethnographic depiction of religious beliefs rather than a demonstration of the spiritual life of Tantric Buddhists through material culture. However, “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art” still conveys a meaningful construct of “Asian-ness.” Namely, the exhibition places the Mongolian Buddhists into the more extensive Asian context of India in the descriptions of paintings. The authors also revealed the diversity and complexity of religious beliefs through the demonstration of the deities and spirits. Finally, they have illustrated that the nomadic Mongolians were attached to material objects and actively used them for prayer and meditation.

To conclude, “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art” is an online exhibition that fulfilled the curatorial goal of material object preservation. However, it did not entirely provide the necessary context of art for the viewers. The authors of the exhibition demonstrated a variety of types of artistic expression to convey the richness of the material culture in religious Mongolia. They presented a Tantric Buddhist identity as a pantheistic culture with an emphasis on ritualistic meditation and high appraisal of art for devotional purposes.

References

Abe, Stanley. 2012. “Pulitzer Foundation Workshop.” Archives of Asian Art 62, no. 1 (Spring): 81–81. Web.

Asianart.com. n.d. “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art.” Web.

Lopes, Rui. 2014. “Meeting Another China: Exhibiting Chinese [Folk] Art and Popular Culture in The Orient Museum.” World Art 4, no. 2 (Summer): 237–261. Web.

Mason, Charles, Andrew Near, and Tom Wagner. 2019. “Deities and Devotion in Mongolian Buddhist Art.” Kruizenga Art Museum Exhibition Catalogs 2: 1–223. Web.

Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2020. A Monastery on the Move: Art and Politics in Later Buddhist Mongolia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.