Introduction

The establishment of democracy in Sudan is the main prerequisite for the development of peace across the nation. Ever since the nation split into South and North Sudan, there have been calls from the international community for the two resultant nations to develop democratic approaches toward running the respective states. However, despite the many negotiations between the respective governments, Sudan has been faced by numerous ethnic conflicts between the societies from either side of the nation.

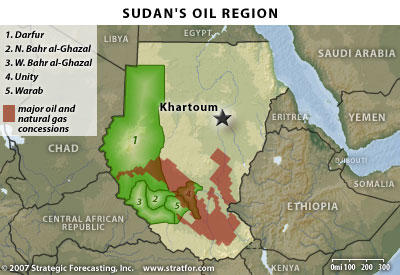

The main reason for the conflict is the quest for ownership of the oil mines in Sudan between the two sides. Sudan has been traditionally characterized by military conflict and conflicts between militia groups trying to govern different regions of the state.

For instance, the war in Darfur has claimed more than 300,000 lives, and it is influenced by the presence of militia groups that fight the government. This has forced millions of Sudanese people to flee from the nation into the neighboring states like Kenya. After the partition of South and North Sudan, the two sides assumed a peaceful negotiation to assume democratic ruling, but they ended up in a conflict that is currently claiming many lives. One of the underlying issues in the conflict is the lack of strong governance to tap the resources of the nation and lead the people into a democratic nation.

Thesis

Sudan has been in internal war for over half a century and the main issue is the war between the government and the militia groups in the nation. The recent partitioning of the state saw the development of a northern side that is characterized by the presence of Islamic extremists in the government, whereas the southern part is characterized by leadership by the militia groups.

Since there is no clear boundary set between the two sides, the northern part has been claiming the parts of the land that are associated with large deposits of oil, whereas the southern people believe that the oil deposits lie on their side. This has led to a conflict that has seen children being recruited by the militia groups to fight against the army from Khartoum. It is apparent that the competition for resources, particularly the oil in the south, is the main barrier for democracy in Sudan.

List of Objectives

This paper will reveal the factors that have led to the recurrent violent conflicts in Sudan, with a close focus on the role that oil has played in influencing the lack of democracy in the nation. It is clear that even after partitioning the nation into the southern and northern region in the quest for peace and democracy, the militia groups and the government in Khartoum are still fighting. The war has led to the killing of children and soldiers, and many civilians in the southern part have been displaced.

Theoretical Overview

Sudan traded in crude oil for the first time in 1999, and this changed the focus of the war in the nation to the quest for control of the oil fields in the south. Over the years, the military has taken over the governance of the nation, and it has negotiated peaceful deals with the militia, which led to the partitioning of Sudan, but oil has continually become a major obstacle to peace and the development of democracy in the nation.

It is apparent that the government and the militia groups have had a good share of the crude oil trade over the past, and the associated revenues have been channeled to the attainment of weapons and the recruitment of more personnel to strengthen each side (Youngs 2008). This has enabled the intensification of the violence, with many children in the militia groups and soldiers on the government side dying on the battlefields. Additionally, the continued expansion of the oil mining process in the nation has led to the displacement of the local communities living in the southern region. This has particularly been instigated by the militia groups as they seek to control the mines (Scheffran, Ide & Schilling 2014).

The resistance from the affected communities has also led to the killing and exiling of innocent civilians trying to protect their property. The militiamen continue to kill the owners of the lands in the oil fields, burning their crops and property to displace them, and this has been the greatest threat to democracy and peace in the south. The figure below shows the oil mines region in Sudan.

While one would expect the government to be in the limelight of developing measures to protect the civilians in the nation, it has actively played the role of displacing the communities living around the oil fields. This has been particularly done to protect the state and foreign oil mining companies in the region (Switzer 2002). According to the government in the north, the presence of the communities in the oil fields is a threat to the companies that have been contracted to mine the crude oil, and since the pastoralists in the region support the militia in pushing the military from the lands, the government has been actively involved in violating human rights by killing the civilians (Jur 2002).

It is quite a pity that despite the partitioning of the nation, the government in the north has continued pressuring for an expansion of its ability to mine oil in the south. It is more worrying that the people in the south and in the north have not benefited from the oil business because the government uses the resources to increase the strength of the military. The government continues to use brute force to control the civilians and silence their demands.

Historical Overview

Sudan is a multi-cultured nation with Islamic people living in the north and the Africans living in the south. Most of the people live along the Nile and other areas associated with reliable rainfall as the main source of water for people and livestock. However, the Africans in the south developed conflicts with the central government that was developed after independence in 1956. It is apparent that the people in the south have always loathed the application of sharia laws by the Islamic leaders in the North (Jok 2015).

This led to the development of militia groups opposing the laws in the south, and for some time the central government allowed the south to practice the autonomy they required in governance to influence peace (Development in Sudan 2016). However, when oil was discovered in the nation, the conflict between the government and the militia groups reignited, and it has continually led to the lack of peace and democracy in the nation (Arbetman-Rabonowitz & Johnson 2008).

The government of Sudan started exploring oil fields in the Western Upper Nile region in the 1980s, and once the discovery of the viable oil fields in the nation was made, it embarked on a plan to displace the communities living in the region. In the 1990s, the government played a major role in the development of conflicts between the communities in the region (Omeje 2010). This was strategically planned through the provision of arms to the conflicting communities, which led to most of the people taking refuge in other parts of the nation and the neighboring states.

This cleared the way for foreign companies to start developing mining stations in the region. Asian companies and Western companies started developing the required infrastructure to mine and transport crude oil from Sudan, including the pipeline and roads.

The human cost of oil in Sudan has been extremely high since 1999 when the nation started producing crude oil commercially. The government has channeled all the revenues to purchasing military hardware and enhancing its power against the militia groups (Salopek 2003). While it has managed to control some of the oil blocks in the south, the militia has mounted a sizeable resistance in most of the viable expansion areas (Patey 2012, p. 563).

The focus on the oil business by the authorities in both the north and the south has seen both administrations ignoring their responsibilities to provide the needs of the civilians (Wesselink & Weller 2006). There are a low number of schools, hospitals, and housing units in both parts of the nation because the authorities spend too much on arming their troops to protect and fight for the oil mines.

Since 2000, the Sudanese government enhanced its ability to meet the needs of the oil mining companies as it looked to increase the volume of oil drilled on a daily basis. The government troops operating around the mines provided the support required for the companies to develop roads to get to the various blocks, and this meant that people living in the blocks would be driven off to the west and the north (Volman 2003, p. 3). Surprisingly, the troops would use violence to chase the civilians away from the region without any compensation.

The UN and other non-governmental organizations compelled the foreign companies operating in Sudan to become ambassadors of peace by influencing the government to protect the human rights of the civilians, but most of the companies claimed that they were not aware of any violations of human rights in Sudan (Sorbo 2010). This highlights the fact that the government of Sudan has actively failed to consider the needs of the civilians while ensuring that the foreign oil mining companies are protected from the hostility of the militia groups and the civilians.

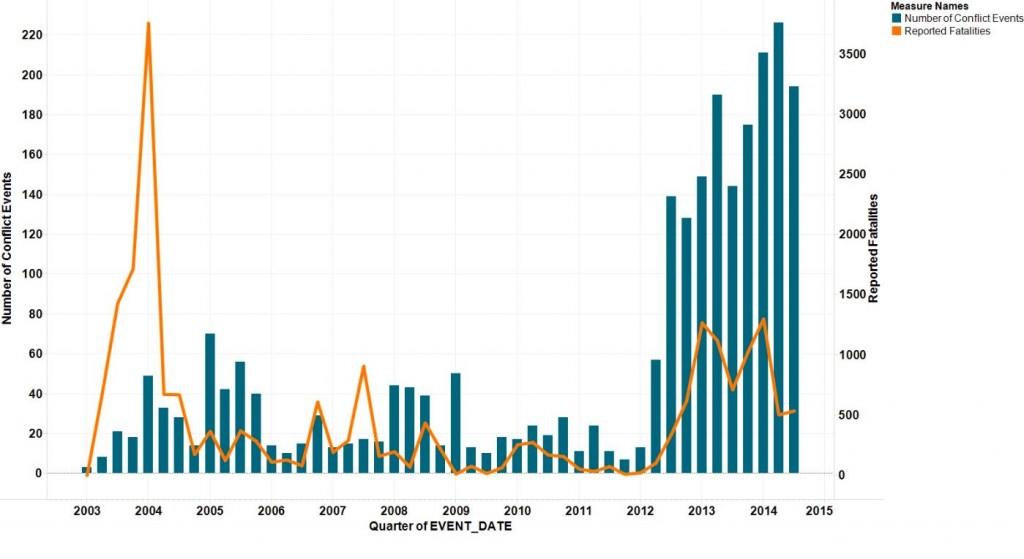

In 2001-2005, the militia groups in Sudan developed new strength through the partnership with some military men from the previous regime and they mounted a resistance against the government to take control of some of the oil mines. The war that ensued saw the government using helicopters to bomb villages and killing civilians indiscriminately (Johnson 2003). This forced most of the people to flee to the neighboring countries for safety as the militia and the government continued to fight for controlling rights in the oil blocks (Straus 2005). It is also apparent the most of the displaced individuals have failed to get back to their homes because the militia groups and the military develop camping sites and garrisons, respectively, in the conquered areas.

In 2011, South Sudan split from the northern side of the nation and it declared independence from the central governance. Many states believed that the move would finally translate into the development of peace in both sides of the nation because it would be associated with the embracement of democratic principles that would influence the protection of human rights (Prendergast & Winter 2008). However, the two sides were still in tension because the government in the north claimed that it had the right to control the oil fields that are currently controlled by the militia groups. In 2013, the President of the southern region claimed that his vice president was organizing a cue on the government (Dufresne 2003).

This led to a split in the political party, which was influenced by propaganda by the politicians who did not agree with the decisions made by the president regarding the resources of South Sudan. Key among the issues was the government’s plans on the oil business. The figure below highlights the reported incidences of violence and death tolls in Sudan.

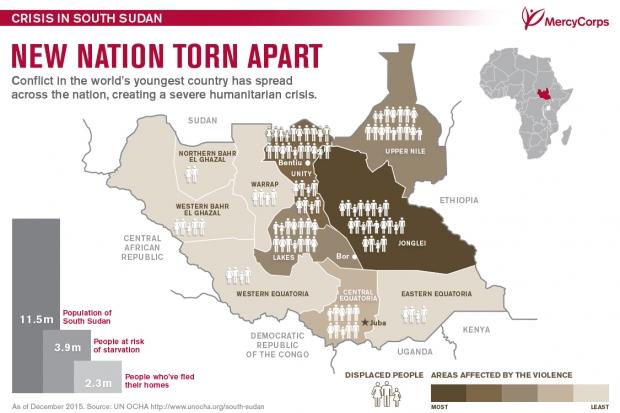

The divergence of ideologies between the political leaders and their followers led to violent conflicts between the people, and the war is still going on. Many Sudanese people have been displaced from the war-torn regions in the south, and this has destabilized the development of democracy in the nation (Patey 2014). The government is still focusing on getting a hold of the national resources while ignoring the fact that many people are dying of hunger in Sudan (Large 2008).

On the Northern side of the nation, the government is still strategizing on the best ways to take over the control of the oil mines, which might result in a war between the two parts of Sudan. However, efforts from the African Union and the United Nations have seen the deployment of military troops from the organizations to protect the displaced individuals and to provide platforms for the political leaders to negotiate (Goldsmith, Abura & Switzer 2002).

The UN is particularly interested in ensuring that democracy prevails in the nation, but the control of oil and other resources in the nation still poses a major threat to peace and democracy in Sudan. The figure below highlights the displacement of the people in South Sudan (Quick Facts: What you need to know about the South Sudan crisis 2016).

Analysis

The oil business has been associated with the development of autocratic states because it needs a ruler with the absolute power to decide the allocation of revenue generated from the business (Brown et al. 2002). This has been seen in states like Libya and Algeria in Africa. Sudan, on the other hand, has always looked to assume democratic governance, but various issues have led to the development of a crisis since the declaration of independence in 1956.

Initially, the southern people in the nation rebelled against the central government because of the religious differences (Obi 2007, p. 17). The central government was applying the Islamic Laws to the pagans and Christians in the south, which led to protests and violent conflicts (Woodward 2008). However, the main threat to the development of peace and the growth of democracy in Sudan was the discovery of oil in the 1980s (Rone 2003).

If there was no oil on the southern side, the government would not have provided arms to the conflicting tribes to reduce the population in the region. The militia in the nation would also have ended their quests by gaining autonomy in the governance of the southern side (Patey 2010). However, the presence of oil changed the focus of both the militia groups and the central government.

Oil is to blame for the lack of peace in Sudan because it provided conflicting groups with sufficient funds to purchase ammunition and to recruit troops to fight against each other. The control of the oil fields has always been the goal of the conflicting sides, but the consequences are dire for the civilians living in the land along with the oil blocks. Most of the land in Sudan is barren because of the extensive desertification of the region (Patey 2007, p. 998).

This implies that most civilians have been forced to live along the rivers. Sadly, the oil blocks are located on some of the most reliable grazing fields in the nation, which implies that pastoralist communities have been the worst affected by the violent excavation by the government and the militia groups (Pantuliano 2010, p. 7).

It is also apparent that despite the current efforts by the United Nations and other international organizations to foster peace and democracy in the nation through military intervention, Khartoum and South Sudan are likely to go to war over the oil mines in the south. This is because the nations did not set a clear boundary in 2011 when they split into Khartoum and South Sudan (McEvoy & LeBrun 2010).

The revenue generated by the oil business is currently benefiting both partitions of the nation, but it is likely that the south will start claiming the mines because they are located in the southern half of Sudan, and they are mainly controlled by the authorities in the south (Carmody 2009). The current political conflict between the leaders in the south is also a major obstacle to democracy because the leaders are jeopardizing the efforts placed by the international community and the internal leaders to grant South Sudan independence from the central government in Khartoum. There is little doubt that the conflict is based on the allocation of resources, particularly the oil in the south, and it is clear that the leaders do not care about the displacement of the civilians because it is a tradition in the nation.

Conclusion

Sudan has the potential to become a very productive nation because it has the proverbial black gold. However, the oil in the nation and the interplay between the political and social issues in the nation has led to a long-term lack of peace among the citizens. The fact that the government has played a major role in the enhancement of suffering and the deterioration of democracy in the nation is quite unfortunate.

Prior to the separation of the state into Khartoum and South Sudan, Sudan saw the government using violence to displace the people living in the lands along with the oil blocks, and this led to many people fleeing to the neighboring countries. This was particularly escalated by the development of a strong militia group that fought against the government.

After the split of the nation into two parts, the world expected the two nations to finally attain the peace required for democracy to blossom, but this has not been forthcoming, especially in the south, where war has recently broken out. There is also high tension between South Sudan and Khartoum as the two sides claim the oil fields. As long as the oil conflict in Sudan remains unsettled, peace and democracy will be difficult to attain.

Reference List

Arbetman-Rabinowitz, M & Johnson, K 2008, ‘Power distribution and oil in the Sudan: Will the comprehensive peace agreement turn the oil curse into a blessing?’, International Interactions, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 382-401.

Brown, V, Caron, P, Ford, N, Cabrol, JC, Tremblay, JP & Lepec, R 2002, ‘Violence in southern Sudan’, The Lancet, vol. 356, no. 9301, pp. 161.

Carmody, P 2009, ‘Cruciform sovereignty, matrix governance and the scramble for Africa’s oil: Insights from Chad and Sudan’, Political Geography, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 353-361.

Development in Sudan. 2016. Web.

Dufresne, R 2003, ‘Opacity of oil: Oil corporations, internal violence, and international Law’, NYUJ Int’l. L. & Pol., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 331.

Goldsmith, P, Abura, LA & Switzer, J 2002, ‘Oil and water in Sudan’, Scarcity and surfeit. The Ecology of Africa’s Conflicts, vol.26, no. 1, pp. 187-242.

Johnson, DH 2003, The root causes of Sudan’s civil wars (Vol. 5), Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Jok, J 2015, Sudan: Race, religion, and violence, Oneworld Publications, London.

Jur, M 2002, ‘A merciless battle for Sudan’s oil’, The Economist. Web.

Large, D 2008, ‘China & the contradictions of ‘non-interference’ in Sudan’, Review of African Political Economy, vol. 35, no. 115, pp. 93-106.

McEvoy, C & LeBrun, E 2010, Uncertain future: armed violence in Southern Sudan, Small Arms Survey, Geneva.

Obi, C 2007, ‘Oil and development in Africa: some lessons from the oil factor in Nigeria for the Sudan’, Oil Development in Africa: Lessons for Sudan after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies Report, vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 9-34.

Omeje, K 2010, ‘Markets or oligopolies of violence? The case of Sudan’, African Security, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 168-189.

Pantuliano, S 2010, ‘Oil, land and conflict: the decline of Misseriyya pastoralism in Sudan 1’, Review of African Political Economy, vol. 37, no. 123, pp. 7-23.

Patey, L 2014, The new kings of crude: China, India, and the global struggle for oil in Sudan and South Sudan, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Patey, LA 2007, ‘State rules: Oil companies and armed conflict in Sudan’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 997-1016.

Patey, LA 2010, ‘Crude days ahead? Oil and the resource curse in Sudan’, African Affairs, vol. 109, vol. 437, pp. 617-636.

Patey, LA 2012, ‘Lurking beneath the surface: Oil, environmental degradation, and armed conflict in Sudan’, High-Value Natural Resources and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 563-570.

Prendergast, J & Winter, R 2008, Democracy: A key to peace in Sudan. Web.

Quick Facts: What you need to know about the South Sudan crisis 2016. Web.

Rone, J 2003, ‘Sudan: Oil & war’, Review of African political economy, vol. 30, no. 97, pp. 478-510.

Salopek, P 2003, ‘Shattered Sudan’, National Geographic, vol. 203, no. 2, pp. 56.

Scheffran, J, Ide, T & Schilling, J 2014, ‘Violent climate or climate of violence? Concepts and relations with focus on Kenya and Sudan’, The International Journal of Human Rights, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 369-390.

Sorbo, GM 2010, ‘Local violence and international intervention in Sudan’, Review of African Political Economy, vol. 37, no. 124, pp. 173-186.

Straus, S 2005, ‘Darfur and the genocide debate’, Foreign Aff., vol. 1, no. 84, pp. 123.

Switzer, J 2002, Oil and violence in Sudan. Web.

Volman, D 2003, ‘Oil, arms and violence in Africa’, ACAS Bulletin, vol. 64. no. 1, pp. 1-5.

Wesselink, E & Weller, E 2006, ‘Oil and Violence in Sudan’, Multinational Monitor, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 44.

Woodward, P 2008, ‘Politics and oil in Sudan’, Extractive Economies and Conflicts in the Global South: Multi-regional Perspectives on Rentier Politic, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 107-119.

Youngs, R 2008, Energy: a reinforced obstacle to democracy?, CEPS, London.