Introduction

The main theoretical result of the Stroop test is the Stroop Effect. The aforementioned phenomenon includes a delay in naming the font color of a word if it has a different meaning, such as a variation in color (Perrey, 2021). There are several interpretations of the Stroop test, for instance, the naming of words written in a different color, the names of colors written in black, and the squares of the selected colors. This test has been widely used to determine various changes in the brain, such as age-related and others (Guzik et al., 2021). Moreover, it can be used for brain development by training certain areas responsible for quick reactions.

Hypothesis

With the help of the Stroop test, one can track cognitive changes that directly contribute to cognitive processes. This study aims to analyze the data obtained from the Stroop test. The hypotheses of the work are focused on the fact that specific demographic criteria of participants influence the time to determine the color. Besides, it is necessary to consider if there is an impact from the neutral or emotionally colored words on the response time.

Background Theory

After discovering this effect, the foreground task among scientists began to explain its occurrence. Thus, it was possible to develop several theories that account for the possible underlying causes of the appearance of the effect based on knowledge of information about the human brain (Ribaupierre & Lecerf, 2019). The first reason is based on the theory of selective attention, which is based on the fact that a person needs more attention to determine the color than to read the word (Daniel & Kapoula, 2019). The spatial-visual system of engagement is responsible for this process according to existing findings. With the help of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, an individual chooses to prioritize focusing on a particular factor. However, more processed pieces of information are needed to determine the color, and therefore there is a delay in response.

The following theory includes a reason related to the speed of information processing. It is known that varied types of information are processed at different rates. Primarily, this is because various parts of the brain and perception sensors are activated (Shichel & Tzelgov, 2018). Current research, therefore, suggests that people read faster than they determine colors. More precisely, the theory provides the concept that one can quickly determine the meaning of a word and its function in the context of a sentence or text. It is worth noting that only single words are used in the Stroop test to ensure perception is even faster. As such, a participant in the test may determine the meaning of the word faster than its color, and conflict arises when one begins to think about the importance of the word instead of the color

The following reason, namely the theory of automaticity, is integral in the proposed phenomenon of automotive reading. Research suggests that individuals may notice that sometimes the reading process occurs subconsciously, and they may not always perceive the information appropriately while reading. It happens when one is distracted by something. Heeringen (2018) and Edlund (2019) mention that even though the optic nerves transmit the read information, it is not processed further. However, studies suggest that in order to determine the color, it is necessary to involve those parts of the brain that can only be activated with complete focus. To choose the color, the brain needs to give full attention; thus, there is a delay with different meanings between the words and colors.

The leading cause of the Stroop effect is the contradiction between what is real and what is perceived by the participant. This is the underlying reason from which all theoretical models originate. It is worth noting that when the subjects are given to read unfamiliar words written in specific colors, they may not have problems with the name of the colors (Green, 2022). According to the aforementioned theories, in instances that a word has a conflicting meaning, in this case, a different color, problems arise. The information seen is a priority; moreover, a person needs to name the actual color of the word quickly (Pan et al., 2019). Based on this, one begins to analyze the priority information, namely what one sees but not what one has studied. Thus, one wants to name what one has read. After all, it takes less time to process such information because it is a priority.

In addition, the theory of resource-saving is relevant to the assessment of the Stroop effect, which explains why one can name the word’s meaning faster, but not the color of the font. As the name implies, the human brain tries to save extra resources, and after reading the word, the brain has a ready-made answer (Hsieh et al., 2018). More precisely, the brain does not need to perform additional processes of designating the word’s meaning since the participant already knows this meaning. However, in the case of the Stroop test, a different condition appears that interrupts the identification of the meaning of the word (Kyamakya et al., 2021). When one sees a familiar word in their primary language, the brain generates an immediate answer based on previous experiences, and there is no need for other thought processes. The reason for this according to current research indicates the saving of resources and time since the brain is tuned for optimal operation.

It is worth noting that findings imply that reading a word takes less time than recognizing, remembering, and naming a color. While reading a comment is one process, several methods need to be done in order to identify the color. Moreover, the brain is used to the “read and name” algorithm without additional calculations of color and value (Bradley & Sullivan, 2018). It is because, in life, one always reads and determines the word’s meaning, but without additional conditions. Thus, the brain will use familiar processes and algorithms in the first place (Kinoshita et al., 2018). In this regard, there will be a delay if other conditions are detected and a person cannot quickly identify what is needed.

The Stroop test is widely used in various self-development and brain training programs within modern psychological practices. It is due to the fact that during the execution of this test, the human brain’s cognitive processes are trained for a while. It includes concentration, attention, focus switching, responsiveness, and others (Nardo & Fioretti, 2021). According to the study of these factors, if a participant showed poor results, the naming of colors was slow, and with many errors, one may show better results after training. The Stroop test demonstrates the ability to focus and concentrate on a specific task at a particular moment (Parris et al., 2020). In addition, it is helpful for the brain to create new connections and switch between them since different sectors are involved in the procedure.

The emotional Stroop test and effect differ in the properties of the words offered to participants. Thus, if an individual observes incomprehensible symbols or words denoting a color in a general test, then in an emotional trial, one is offered words in which emotion has an impactful effect. As a result, it was found that people needed more time to name the color of emotionally colored words than neutral ones (Herbert et al., 2018). Thus, this phenomenon is called the emotional Stroop effect, and emotionally colored words can include both positively and negatively encoded words. Dependence on the positivity or negativity of the vibrant coloring of words and the test results was not found.

There is a critique of the effect that reflects several primary features. First, many researchers are confused by the accuracy of the test results. There is a significant difference between the results of different samples. Moreover, Ong (2021) and Baron (2018) mention the test depends on various factors, such as the subjects’ national, behavioral, psychological, and additional characteristics. The results will also depend on the events experienced by the person, on one’s mood and thoughts. Thus, if an individual is worried about something, one will show worse results than one could demonstrate. The study suggests that a participant may think about the event and be less focused if something happens (Huang et al., 2020). Finally, the procedure varies from study to study, affecting the test’s accuracy.

The results of the emotional Stroop test will also depend on the severity of cognitive abilities and individual experiences. Thus, the greater the degree of personal experiences of an individual, the more time one will need to determine the color of emotionally charged words (Lemaire, 2021). Research suggests that emotionally colored words will evoke increased emotions, memories, and thoughts associated with this word. This may be a personal experience of a memory or an emotion that the individual has observed in the past. Farmer and Matlin (2019) and Hogan (2019) state that people who pay more attention to their emotions pay more attention to the emotions caused by a word. Thereby, a participant might spend more time as part of the process and be occupied with interpreting and contemplating the emotions associated with the word. Due to this, this study hypothesizes that participants had equal response time regardless of triggering words used against them.

Methods

The methodology of the test consisted of the administration of an online emotional Stroop Test, the data analysis using descriptive statistics and a t-test, and adherence to ethical considerations. In the online Emotional Stroop Test, participants were presented with various words and instructed to choose the color word (ink) that appeared on their screens. The data utilized in the study was randomly picked from this test, and 10 participants were used, six females and four males. The participants’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years. Since the data was collected online, no specific additional qualities were required for anyone to participate. However, the collected data was monitored in order for the results to not have any missing data or answers from the participants.

Data analysis for collected information was performed using statistical software known as SPPS. The software calculates descriptive statistics of the data that was collected. The main aim of descriptive statistics is to provide basic information about the data collected and show potential relationships between variables. Additionally, the data compared the means of three different trials using an appropriate t-test. These means were compared to determine if trials have statistical significance at p<.05.

In addition, the study was carried out by observing the principles of ethical considerations. First, all participants took part in the study voluntarily. Further, each participant was fully informed about the course of the experiment in detail, what data would be collected, and what was required from the participant. This study has no potential for any harm to the participants, either moral or physical. In addition, confidentiality, anonymity, and timely and complete disclosure of the results were maintained. No category of data covered during the study contains confidential information. Moreover, it is published only with the consent of the participants.

Results

Data collected from Online Emotions Stroop Test: participant, age, sex, and the number of trials.

After analyzing descriptive statistics and appropriate t-tests in the data collected, the results below were obtained and assessed.

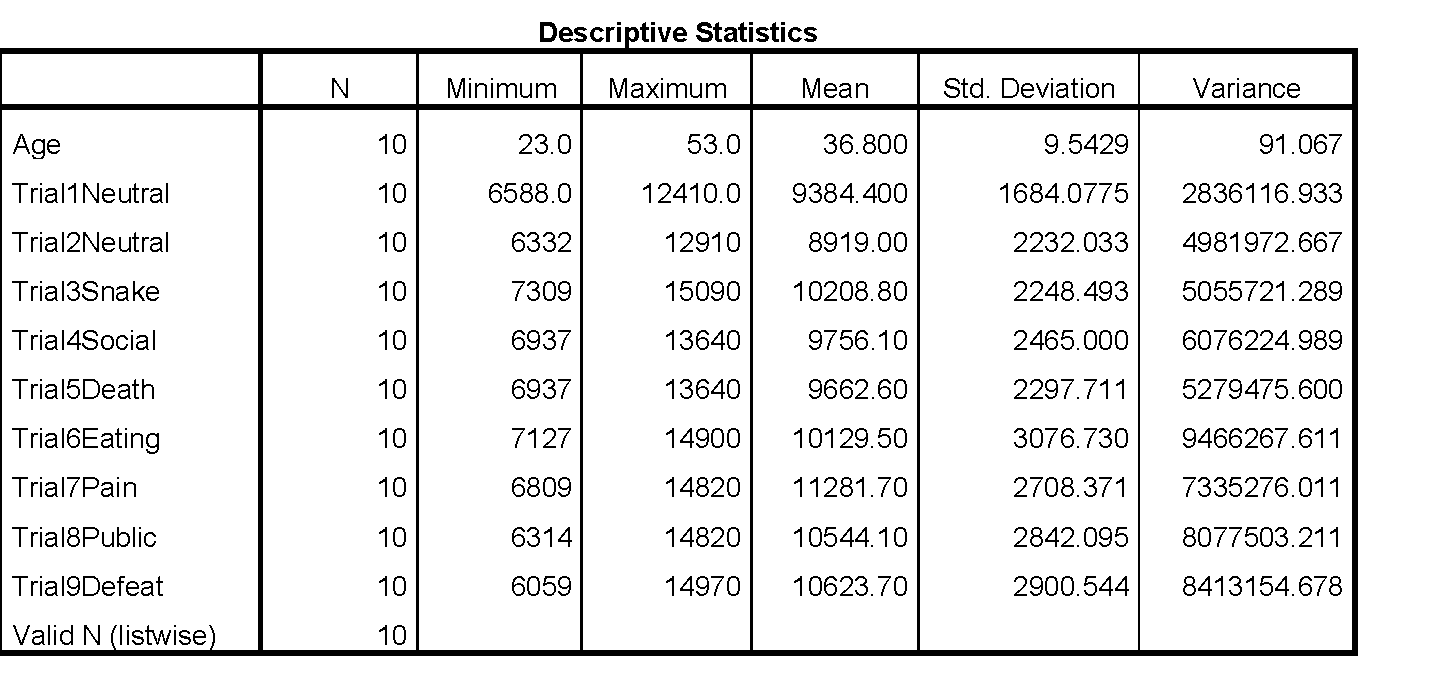

Table 1: The Stroop Test Descriptive Statistics Results

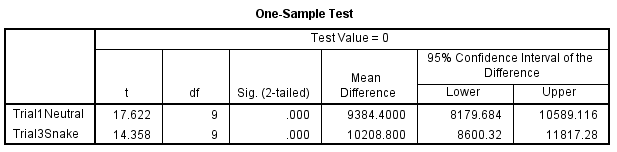

Table 2: Neutral (Trial 1) vs. Snake (Trial 3) Means

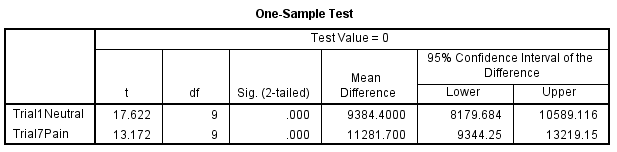

Table 3: Neutral (Trial 1) vs. Pain (Trial 7) Means

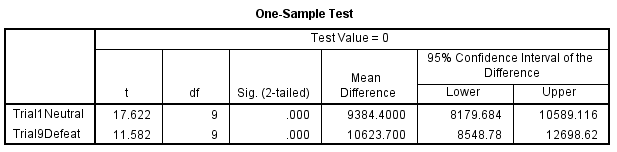

Table 4: Neutral (Trial 1) vs. Defeat (Trial 9) Means

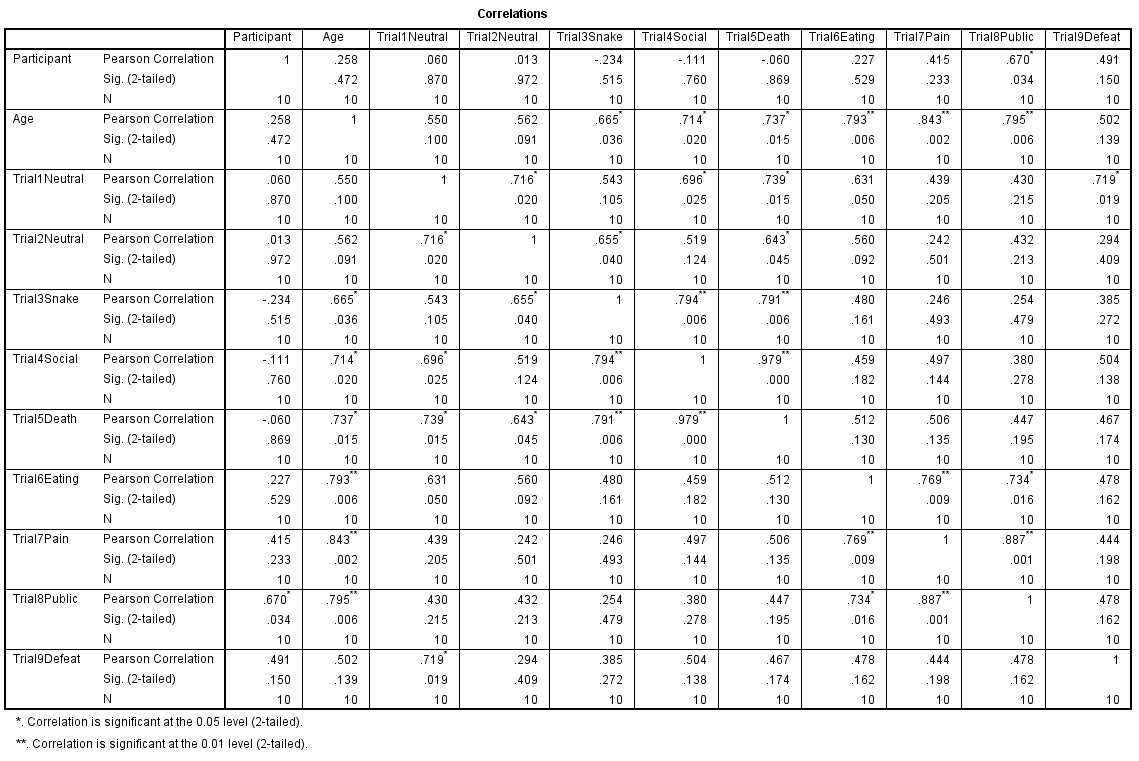

Table 5: Correlation between Participants, Ages, and Trails

Table 1 shows that all the trials have a significant variance while age has a relatively small variance factor. This indicates that values of the trials were spread out among the trials while values of age were closer to the mean. On the other hand, tables 2, 3, and 4 show no statistical significance because p<.05. The null hypothesis will be rejected to conclude that trial participants have different response times depending on the words used to trigger participants’ emotions. Finally, Table 5 shows the correlation between age, participants, and trials.

Discussion

For practical analysis of the emotional Stroop effect in relation to the participant responses, it is necessary to base it on specific results. As such, the report must obtain results of the Stroop test, where subjects of different sexes and ages had to fill in the color of a word in order to utilize relevant data. The words included neutral and emotionally colored words and were divided into several groups. The experiment included nine trials with twelve words in each test. The first two trials included neutral words such as “table,” “umbrella,” “chair,” and more.

The remaining trials were divided into seven main themes; for example, the theme “snake” contained such words as “poison” or “cobra.” The topic “pain” had words such as “headache,” “bleeding,” and others. Once a comment appeared on the screen, participants were asked to select the color of the word (ink) by using their keyboard’s R, B, G, and Y keys. ‘R’ stood for red, ‘B’ for blue, ‘G’ for green, and ‘Y’ for yellow. Once each trial was completed, the average time taken to select the word colors (measured in seconds) of the words in the list was recorded.

Both male and female participants in the data collection were roughly the same age. In other words, there were both younger and older men and women partaking in the population of the experiment. This is significant because it may be used to assess how aging affects the speed at which people can identify colors. Age and gender, however, were not taken into account to demonstrate whether the respondents’ gender had any impact on the outcomes. It is important to note that the first inference drawn from the test findings is the relationship between participants’ ages and how quickly they could identify colors. Therefore, the reaction rate did not change as the individuals’ ages increased for both the male and female subjects.

Accordingly, the lowest results were demonstrated by a 23-year-old man and a 25-year-old woman. At the same time, the magnitude of the reaction depends on age, regardless of the trial, that is, both for neutral words and emotionally colored ones. However, there is a difference between trials at different ages, and no regularity was found. It is because such testing should take into account many personal factors. These include the participant’s character, temperament, mood, personality style, experiences, physical condition, health, and other personal experiences (Balconi & Campanella, 2021). A regularity was revealed only in the aspect of age, which consisted of an increase in reaction time with increasing age and a decrease in time with a reduction in the period, respectively.

It is worth noting that along with the age pattern, there is also an average pattern depending on neutral words and emotionally colored ones. Although this pattern is not observed in all participants, if one analyzes the results in a general aspect, one can notice the rule. It lies in the fact that, more often, the reaction time is longer for emotionally colored words, regardless of age or gender. Such indicators are found in almost all participants, except, for example, a 23-year-old man. For this participant, the time indicators for determining all groups of emotionally colored words, except for the “snake” trial, are lower than the time for deciding the first two neutral trials. At the same time, a 35-year-old man showed almost the same detection time for neutral and emotional problems, excluding the “defeat” group, which was significantly higher.

Interestingly, the longest reaction time in this test was captured by a 53-year-old male in the trial 3 “snake” group. This indicator was about 15 seconds, which indicates a solid emotional significance of this group for the participant. I hypothesize that this participant may have a phobia of snakes; therefore, one demonstrated such a high result. Other than that, it can be formulated by past experiences; for example, a participant or one’s family member was bitten by a snake. At the same time, a 25-year-old woman in the “defeat” group showed the lowest reaction rate. It can be interpreted as a lack of passion for sports or competition experience since defeat does not cause emotional stress.

Speaking more about the test results, the interesting point is that Trial 7 Pain, Trial 8 Public, and Trial 9 Defeat had the most scores above 10 seconds. At the same time, Trial 2 Neutral had only two indicators above 10 seconds in a 53-year-old male and a 47-year-old female. One may notice that the rule of performance-by-age ratio is retained in the neutral groups. The two most extended periods were for the two oldest participants in the second impartial trial. Although there were four indicators above 10 seconds in the first neutral trial, the age of the participants was 33 and above. At the same time, three of the four participants with an indicator of above 10 seconds in the first neutral trial had an age above 45. The ratio of age and time is preserved both in the first and second impartial trials and in some emotionally colored groups.

Finally, discussing what can be done to further this study, several aspects may be significant for future research. First, it is necessary to supplement the participants’ information to make the analysis more accurate. This information should include temperament, personality, health status, background events, substance use, and the participant’s mood. It is necessary because each of these factors influences the time of determining the color, that is, the qualitative and quantitative information of the study (Pool & Qualter, 2018). Such data from the study’s core formulates this proposal’s value. Finally, it will be valuable in terms of the field in general and will allow more accurate results to be obtained. In turn, it will help determine the factors influencing the performance and develop new theoretical bases, considering the above data.

References

Balconi, M., & Campanella, S. (2021). Advances in substance and behavioral addiction: The role of executive functions. Springer Nature.

Baron, I. S. (2018). Neuropsychological evaluation of the child: Domains, methods, and case studies. Oxford University Press.

Bradley, B. R., & Sullivan, T. O. (2018). Dairy products. MDPI.

Daniel, F., & Kapoula, Z. (2019). Induced vergence-accommodation conflict reduces cognitive performance in the Stroop test. Scientific Reports 9(1247).

Edlund, J. E. (2019). Advanced research methods for the social and behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Farmer, T. A., & Matlin, M. W. (2019). Cognition. (10th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Green, C. D. (2022). Classics in the history of psychology. Web.

Guzik, A., Perenc, L., & Druzbicki, M. (2021). Disorders of motor, somatic and cognitive development in children with neuro dysfunctions. MDPI.

Heeringen, K. (2018). The neuroscience of suicidal behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Herbert, C., Ethofer, T., Fallgatter, L. J., Walla, P., & Northoff, G. (2018). The Janus-face of language: Where are the emotions in words and the words in emotions? Frontiers Media SA.

Hogan, T. P. (2019). Psychological testing: A practical introduction. (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hsieh, S. S., Huang, C. J., Wu, C. T., Chang, K., & Hung, T. M. (2018). Acute exercise facilitates the n450 inhibition marker and p3 attention marker during the Stroop test in young and older adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(11).

Huang, Y., Su, L., & Ma, Q. (2020). The Stroop effect: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis in healthy young adults. Neuroscience Letters, 716(1). Web.

Kinoshita, S., Mills, L., & Norris, D. (2018). The semantic Stroop effect is controlled by endogenous attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 44(11), 1730–1742. Web.

Kyamakya, K., Machot, F., Mosa, A. H., Bounchachia, H., Chedjou, J. C., & Bagula, A. (2021). Emotion and stress recognition related sensors and machine learning technologies. MDPI.

Lemaire, P. (2021). Emotion and cognition: An introduction. Routledge.

Nardo, F., & Fioretti, S. (2021). Recent advances in motion analysis. MDPI.

Ong, E. (2021). Early identification and intervention of suicide risk in Chinese young adults. Springer Nature.

Pan, Y., Han, Y., & Zuo, W. (2019). The color-word Stroop effect driven by working memory maintenance. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81(1), 2722–2731. Web.

Parris, B. A., Augustinova, M., & Ferrand, L. (2020). The locus of the Stroop effect. Frontiers Media SA.

Perrey, S. (2021). Studying brain activity in sports performance. MDPI.

Pool, L. D., & Qualter, P. (2018). An introduction to emotional intelligence. John Wiley & Sons.

Ribaupierre, A. D., & Lecerf, T. (2019). Cognitive development and individual variability. MDPI.

Shichel, I., & Tzeglov, J. (2018). Modulation of conflicts in the Stroop effect. Acta Psychologica, 189(1), 93-102. Web.