About the Case Study House

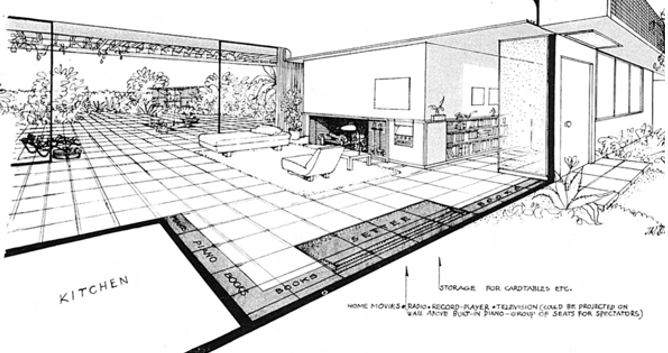

The main idea, to which the article was devoted not so much, as the conceived construction project, lies in the desire of the creator to perpetuate the postwar architectural art. John Entenza, editor-in-chief of the California Journal of Contemporary Architecture, commissioned the most talented architects from scratch to build several houses in Southern California (Entenza 37). Entenza did not seek to solve the social issue of housing the homeless or as soon as possible to sell the buildings – the experimenter was driven by a desire to see what modern professionals invest in the phenomenon of the house.

It is essential to say in what historical era this project was conceived. Of course, such ideas may well be realized today, but such an event for post-war America was grand and bold. The troubled economy and social crisis have not yet left the citizens of the country, and, as if to distract them from the problem, Entenza is starting an experiment. It turns out that the houses built are an iconographic legacy of the architectural thought of the time. Moreover, it was assumed that such housing, affordable for the middle class, would be trendy in the post-war period of rapid construction.

The results achieved in the construction of economical houses showed all architects and developers that it was possible to create beautiful and inexpensive housing. It is safe to say that this experiment has mostly determined the landscape of postwar Los Angeles. The minimalism with which houses were created is at the heart of most modern architectural ideas in housing construction. Such houses have laid the foundation for future projects that combine efficiency, technology, and safety.

About the Architecture Culture 1943-1968

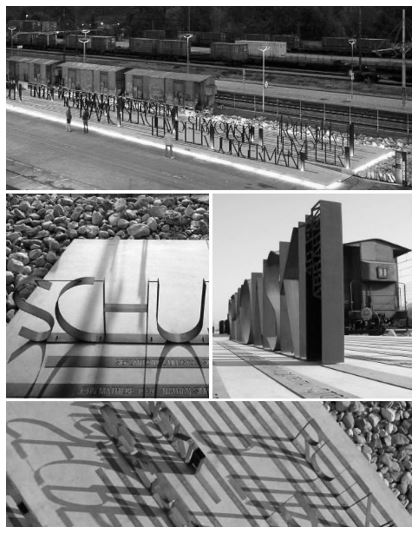

This text is difficult to define as unambiguous because it reflects two views on the same issue. The topic raised by Ockman and Eigen concerns the discussion of monumentality and the right to monumentality in pre-World War II architectural creations (27). This work provides a historical perspective on the debate, iconic figures, and faces, as well as nine criteria for what a monument should reflect. One way or another, the basic idea is that monumentality is an inalienable right of human culture to create its heritage.

The work discusses more than one historical period – the central part is reduced to the pre-war debate, but closer to the middle of the article is a discussion of how the problem under study has affected the architecture of 1970-1980. However, it is worth noting one crucial detail that underlines the relevance of the ongoing debate. In fact, experts explored the importance of monumentality in architecture at a time when the world was divided into fairly clear parts: Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s USSR, and the European powers. The abundance of definite opinions led to the need to review such seemingly basic concepts as a monument.

The ideas expressed by Ockman and Eigen regarding what the monument should be like predetermined modern trends in the construction of functional spaces. In affirming the right to the heritage of human culture, the authors called for a move away from the traditional understanding of the meaning of the word “monument” – it is not only a tribute to war or people but also the desire of man to perpetuate his work (Ockman and Eigen 29). Their nine points can describe current trends in the construction of cultural parks and sites.

About Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture

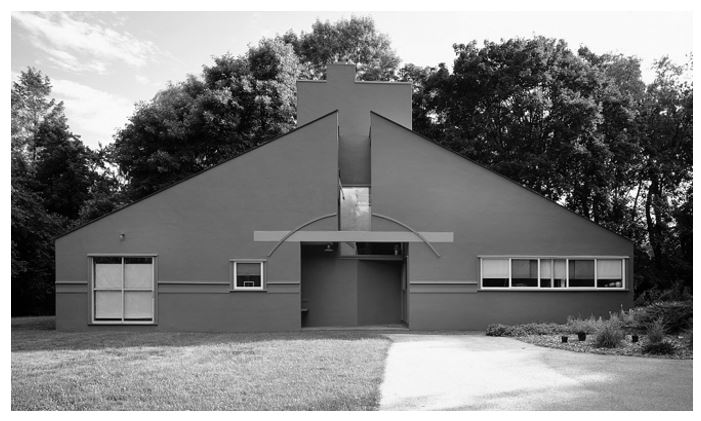

The focus of this work is the issue of contrast and contradiction in construction solutions. Criticizing contemporary (at the time of the 1960s) architectural art, the authors discuss a protest that was becoming normal and even desirable for professionals (Venturi, Stierli, and Brownlee, 9). According to Venturi, Stierli, and Brownlee, architects should not put restrictions on the style or courage of decisions – instead of the usual unambiguity and mediocrity, and the creators should pay attention to mixing and hybridity of styles (8). As if responding to the modernist “Less is more,” the authors write “More is not less,” demonstrating not only his rebellion with all the classics but also the direction of architectural thought at the time (16). The text was an extraordinarily bold and unexpected experiment for the 1960s in New York City.

America, which had already experienced the horrors of war and became on the modernist path in architecture, suddenly presents the world with ideas that were not natural for that time. The functionalism of modernism, its stereotypical forms, and ideas have exhausted themselves. Excessive rationalism of modernist solutions created an atmosphere of despondency, while everything around required the introduction of a jet of originality into every creation. The words of the authors exploded the foundations of modernism, on which several generations of architects prayed diligently. From that moment on, modern architecture took the big road of individual and experimental architecture without rules. Such bold criticism could not but provoke the emergence of post-modernist architecture, which is characterized by citations and interpretations of historical forms and fragments, as well as a mixture of different styles.

Works Cited

“50 Modern Living Rooms That Act as Your Home’s Centrepiece.”Home Designing, no date. Web.

Boer, Rene. “8 Reasons You Will Also Like Postmodern Architecture In 2016.” Failed Arhcitecture. Web.

Entenza, John. “The Case Study House Program.” Arts & Architecture, vol. 62, no. 1, 1945, pp. 37-39.

“Highsmith (Carol M.) Archive.” Library of Congress, no date. Web.

Ockman, Joan, and Edward Eigen. Architecture Culture 1943-1968: A Documentary Anthology. Rizzolo, 1993.

“(Post)Modern Monuments: 20 Worthy Architectural Memorials.”Web Urbanist, 2011. Web.

Venturi, Robert, Martino Stierli, and David Bruce Brownlee. “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.” The Museum of Modern Art, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977, pp. 8-19.