Introduction

In recent years, one of the main challenges facing educators has been providing education programs to help young people to acquire the knowledge, skills and understanding needed to optimise their sexual health. For a long time, ‘sex education’ dwelled on the human reproductive system and recommended sexual abstinence on young people.

In recent years, the concepts of sexual health and sexual health promotion has began to take the place of this kind of program, and in the UK, schools have become the primary site for programs to advance sexual health for young people.

Sex and HIV education programs that are focused on a written curriculum and that are implemented among groups of youth in schools, clinics, or other community-based organizations are a promising type of involvement to bring down adolescent sexual risk behaviors. This paper examines the effectiveness of sex education in both primary and secondary schools in the UK. The paper will mainly focus on an analysis of the impact of sex education on sexual risk-taking behaviors among young people.

Literature Review

Young People are Sexual Beings

Gourlay (1994) argued that it is necessary for teachers to pragmatically accept that young people are sexual beings, and that their sexuality will certainly find expression, not only in how they act, but also in how they think and feel.

There is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that young people are sexual beings from a very early age, and that increasingly they are becoming sexually active from early in their adolescence. In a national survey of UK secondary school students, by year 10, the majority were found to be sexually active in some way.

Eighty percent participated in deep kissing, 67% had genital contact, 45.5% gave or received oral sex and 25% had experienced vaginal intercourse. By year 12, just over half had experienced vaginal intercourse. In the same survey, it was established that 30% of young men and 26% of young women aged 16 to 19 reported their first heterosexual intercourse occurring before age 16 (Starkman, 2002).

A 2001 study in New Zealand investigated the gap between what young people aged 17 – 19 learned in sexuality education and what they do in practice. This study reported that the participants gained information about sexuality in two ways, from sexuality education, and from personal sexual experience. The types of sexual knowledge young people were most interested in, and which they identified as lacking in sexuality education, centered on a ‘discourse of erotics’ (Allen, 2001).

Therefore, a critical factor for the success of any program promoting sexual health is to acknowledge that young people are sexual beings, and that the majority of them will be sexually active in some way. This will help in ensuring that the content of any program is appropriate to the needs and interests of the entire group, including those who are, and those who are not sexually active.

The Learning Environment

While the content of school-based sexual health education is vitally important, the context in which such education is delivered is equally important. Sexual health curriculum content is vastly different from other school subjects and both the environment and the approach of those teaching sexual health programs need special preparation and attention.

Gourlay (1994) suggest that teachers need to be approachable, that students should be able to ask explicit questions, including those about the physical aspects of sex. Furthermore, students should be able to make comments that are not dismissed by the teacher. Gourlay identified four interrelated processes that work to reduce students’ discomfort in the classroom setting.

These include the teacher as protector and friend, that there should be a climate of trust fostered between students and that the program should be seen as fun. The author argues that students should receive sex education in familiar class groupings, that the teacher should, ideally, attempt to minimise disruptions, and that they should work towards eliminating hurtful humour while maintaining an approachable manner.

Curriculum

Allen (2001) argues that in order to empower young people to be responsible for their own sexual health, sexuality and relationship education programs are needed. This author recommends that such programs focus on providing a forum for discussion of ideas about sexuality, promote respect for differences and the views and values of others, as well as promote a positive view of one’s own body and sexuality.

This view of sex education as a forum where respect and positive views are promoted is at variance with the traditional sex education class, which has mainly focused on providing information about reproduction and disease transmission and a number of authors posit that information alone is not sufficient to ensure safe and responsible sexual behaviour.

Gender

Young people’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviour about sexuality is strongly gendered, with different understandings, beliefs and behaviours being ascribed as ‘appropriate’ for young women and young men. This is highlighted in a report by Starkman (2002) and calls for some sexual health education to be gender specific to ensure that young women and men have the knowledge and understanding necessary to ensure that they can make sound decisions and minimise risk.

Because of this gendering, relations between young men and young women can present challenges in the classroom context when teaching about sexual health. Many young people experience discomfort when asked to discuss sexual matters, and this may be particularly so in a mixed gender environment, where they may be reluctant to ask questions or participate actively in lessons.

Research Methodology

Research Design

For the research, the study used the survey method, which was conducted by use of questionnaires. This method was used for data collection because it enabled the researcher to solicit for information that might not have been available on textbook pages and to bring successful completion of the study.

Target Population

For this research, the program focused on 100 adolescents or young adults aged 9-19 years from various primary and secondary schools in the UK. In order to ensure fair gender representation, 50 of those sampled were boys and the rest were girls.

Sampling Technique

The researcher used simple random sampling technique method in the selection of the sample size from the identified population of the study. This was done to reduce bias. An in-depth interview was also held with various interest parties who in this case were teachers and health representatives.

Research Collection Tool/Instruments

The instrument used for data collection were questionnaires, which included mostly multiple-choice questions of Yes and No. Copies of these questionnaires were administered to the sampled population and collected in the same manner.

Validity of the Research Instrument

Validity as defined by various researchers means something that is effective because it has been done with the right formalities. In order to give validity to the research instrument, the researcher used a set of twenty choice questions to make up a questionnaire that was presented to the respondents. The questionnaire was first submitted to the supervisor for validation and reliability.

Data Collection Procedures

The investigator delivered and collected the questionnaires to and from the respondents. Although using the email would have been a more convenient method of distributing the questionnaires, the researcher opted for personal delivery in order to minimise cases of the questionnaires getting lost on their way back to the researcher. In addition, some respondents could not find time to fill in the questionnaires unless they were encouraged by the researcher to do so.

Data Analysis

After the respondents had returned the questionnaires, the obtained data was edited for accuracy, importance and comprehensiveness. A final descriptive analysis was then carried out using graphic representation and charts.

Data Analysis and Discussion

Table 1: Are you sexually active?

The majority (94%) of the respondents reported that they were sexually active with only a mere 6% indicating that they were not yet sexually active.

Table 2: Do you practice safe sex?

Among participants who indicated that they were sexually active, 54% indicated that they practiced safe sex with the rest (46%) admitting that they did not. In this category, an even larger percentage (72%) indicated that at one time they contracted an STI while only 28% indicated that they had not.

Table 3: Have you ever participated in deep kissing?

In this category, 99% of the participants indicated that they had participated in deep kissing at one point in their life with only 1% answering in the negative. In the category of those who had taken part in deep kissing, a big majority (86%) indicated that they first kissed when they were less than 12 years, 12% indicated that they participated when they were below 18 years while only 2% indicated that they had taken part in deep kissing when they were over 18 years of age.

Table 4: At what age did you participate in deep kissing?

Table 5: Is sex education taught in your school?

When asked if sex education was taught in their school, all the participants (100%) indicated that they had some form of sex education. However, an astonishing 92% indicated that they were dissatisfied with the content of the education with only a mere 8% showing satisfaction with the program.

Table 6: Is sex education taught in single sex or mixed classes?

When asked this question, 60% indicated that they were taught sex education in single sex classes while the remaining 40% indicated that they were taught in mixed classes. Among those who were taught in mixed classes, 98% felt that this was wrong with only 2% agreeing to this approach.

Table 7: Is sex taught in mixed age group classes?

When answering this question, 58% indicated that sex education was taught in mixed age group classes while 42% indicated that they were categorized according to age groups.

Table 8: Do you trust your teacher enough to confide in him/her matters concerning your sexuality?

The majority of the respondents (82%) indicated that they did not trust their teacher enough to share matters regarding their sexuality with only 18% indicating that they did so.

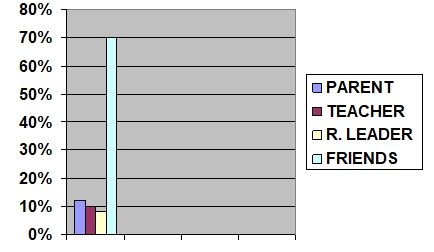

Fig 1: Whom do you trust enough to share matters regarding your sexuality?

When asked this question, 12% indicated that they were comfortable sharing with their parents, 10% indicated that they were comfortable sharing with their teachers, 8% indicated that they would share with a religious leader while an amazing 70% indicated that they were comfortable sharing with their friends.

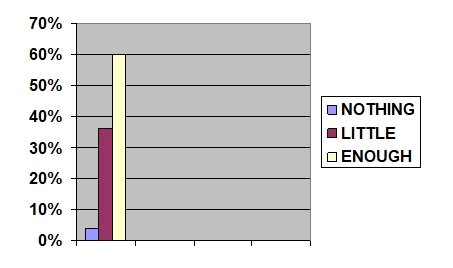

Fig 2: What is taught about HIV?

In this poll,4% of theparticipants felt that nothing was taught about HIV, 36% felt that little was taught while the larger percentage (60%) felt that enough was taught on the subject.

Table 9: At what age/level should sex education in schools begin?

In this category, the participants unanimously agreed that sex education in schools was supposed to be introduced between 5-10 years.

Discussion

From the above analysis of data, it is obvious that most students become sexually active by the time they are ten years old. While all the schools in the UK teach some form of sex education, it is obvious that the education is not as effective since a large percentage (92%) of respondents indicated dissatisfaction in the education.

This is replicated in the large percentage of respondents who felt that there was no enough trust between them and their teachers to enable them to share matters of their sexuality. The situation is even made worse by the large number of respondents (70%) who indicated that the only person they were comfortable sharing such matters were their peers.

Recommendations

From the interview questions with participants, the following is recommended.

- In the short term, it is imperative that sex education be offered to all adolescents in the UK.

- It is important that well-trained, knowledgeable persons execute and instruct sexual health education programs.

- From a proactive standpoint, creation of a comprehensive sexual health education curriculum is necessary for all UK institutions of learning.

- Health professionals should consider the viability of a teen clinic, which provides sexual health education and related health care.

- There should be support to keep the existing programs up and running.

References

Allen, L 2001, Closing Sex Education’s Knowledge/ Practice Gap: The Re-conceptualisation of Young People’s Sexual Knowledge’, Sex Education, vol. 1 no. 2, pp. 109-122.

Gourlay, P. 1994, ‘Adolescent Sexuality: A Fact of Life’, Youth Studies Australia, vol. 13 no. 2, pp. 56-57.

Starkman, N 2002, ‘The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education’, AIDS Patient Care and STDs vol. 16 no. 7, pp. 313 – 318.