Introduction

Organizations operate in an environment that requires some changes to remain competitive. Consequently, they cannot operate efficiently in the long term without learning and development either wholly or at an individual level (Easterby-Smith, Crossan & Nicolini, 2005, p.783).

The goal is to ensure that an organization has the capability to sense any changes in the external and internal environment and then adapt to meet the new demands. The subject of organizational learning and development is a critical issue that is rooted in the organizational theory.

The issue finds central applications in the human resource section of any organization (Bontis, Crossan & Hulland, 2002). Although there are several models for organizational learning, the goal of this paper is to discuss the applicability of Peter Senge’s learning and development model within an organization as shown in appendix 1.

Peter Senge’s Learning and Development Model

According to Peter Senge, learning organizations are organizations, which make it possible for all members to develop, and be transformed in a continuous way (Fulmer, Keys & Bernard, 1998). Environmental pressures cause organizations to embrace change through learning alternative ways of getting things done in the most effective and efficient manner.

From Senge’s concept of organizational learning, organizations encourage learning through enabling people to do things in an interconnected and comprehensive manner (Senge, 2004).

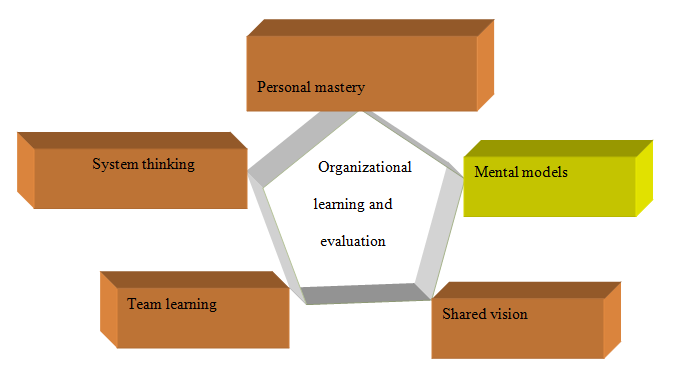

In this sense, organizations imitate communities by encouraging people working in them to develop total commitment to them. Senge’s model for organizational learning is based on five main pillars. These are “systems thinking, mental models, team learning, personal mastery, and shared vision” (Senge, 2004).

System thinking is the main building block of Senge’s learning and development model. In his book Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Senge brings a wealth of information on how theory can be deployed in an organization to address various issues and organizational questions.

For Senge, systematic thinking is the pillar for enhancing learning irrespective of the industry in which an organization operates. Such thinking forms the sphere, which integrates all different facets of an organization to operate coherently (Senge, 2004).

System hypothesis enables people to tackle and understand the whole while still paying attention to the existing interrelationships between the whole and the constituent components. Senge argues that people learn through experience.

Consequently, a learning and development model needs to take care of determining how the experience gained by workers in an organization influences the different elements of an organization together with the whole (Fulmer, Keys & Bernard, 1998).

The theoretical concept of organizational learning as applied in Senge’s model suggests that people can analyze an organization in the effort to learn about it better by scrutinizing it from the paradigm of being composed of a number of objects, which are bonded together.

Thus, learning organizations deploy system thinking as a primary tool for assessing an organization and putting in place information systems, which help in measuring the performance of their organization as a whole coupled with its constituent components (McHugh, Groves & Alker, 2008, p.210). The main argument for this model is that a whole cannot exist within elements.

Learning serves the function of ensuring that all components are developed consistently and together for the whole to develop. For instance, it is perhaps impossible for an organization to produce and sell superior products without letting all its components such as chain supplies and research and design among other to learn from experiences on areas of weaknesses for an organization.

This means that, for learning organizations to be created, it is necessary that all characteristics become apparent and harmonized at once. However, Easterby-Smith, Crossan, and Nicolini (2005) are opposed to this line of argument by claiming that factors that are definitive of a learning organization are not acquired simultaneously. Rather, they are developed gradually as an organization grows.

In the second pillar, personal mastery, Senge argues that individuals within an organization must be committed to learn. Such commitment is crucial since organizations whose people learn faster end up possessing better competitive advantage (Senge, 2004). Individual learning takes place through training and development. Hence, learning and development measurements seek to identify what people learnt in a training program.

Instructors have clearly defined objectives. Therefore, learning outcomes are clear. This includes knowledge, attitude, and skills. Any learning program is meant to create additional knowledge about an organization or new ways of accomplishing various organizational tasks (Senge, 2004).

Where people are lowly motivated to conduct some tasks because of inadequate knowledge about new changes introduced in an organization, Mants (2003) argues that the primary focus of learning program should aim at changing the attitudes of employees for learning to be effective (p.295). In this regard, evaluation process needs to pay attention the things that have been trained.

This strategy is a quest to test or measure personal mastery. Thus, it is vital to develop an organization culture, which encourages people to practice personal mastery always. From this basis, a learning organization is best described by a combination of individual learning. However, Senge does not illustrate the method, which can be used to transmit personal knowledge into managerial learning.

Mental model encompasses all assumptions that are possessed by the organization and its people. Their evaluation is important since mental models may act to create the wrong image and/or perception of an organization. This may hinder efforts of making employees motivated to their work. To create a learning organization, it is important to challenge the organizational mental models.

These manifest themselves in the form of values, behavior, and even norms (Senge, 2004). The degree to which an organization is capable of maintaining learning is the culture, which is a function of the capability to deal with the challenge of confrontational attitudes by replacing them with open culture to foster trust together with inquiry (Senge, 2004).

The primary goal of evaluation of mental models is to ensure that an organization is capable of unlearning values and norms, which are not desired.

Learning is a process that requires motivation. From Senge’s model, for organizational learning and development to occur, shared vision is an important aspect, which aids in the identification and measurement of common identities, winch help an organization to focus its attention together with energy to learning (Mants, 2003). A triumphant mental picture is built by the character image that is possessed by the workforce.

This means that traditional hierarchical structures of organizational governance may impede an organization from benefiting from the success that is associated with the ability to build common shared visions. In such systems, employees are not given a room to take part in the decision-making process of an organization.

Hence, the capacity of an organization to foster learning and development may be evaluated from the basis of the degree to which its governance and administration structures are decentralized. In most instances, a shared vision involves the development of the capacity to out power competitors.

Nevertheless, Senge holds that this vision is merely a short-term or a transitory vision (Senge, 2004). Hence, focus is critical on the development of intrinsic goals defining a shared vision with the capacity to have long-term implications to an organization.

Team learning is the last element of Senge’s model for organization learning and development. It involves the accumulation of different individual learning elements. The evaluation of the ability of an organization to build a self-learning team culture is important since shared team learning is pivotal in enabling the staff of an organization to grow more quickly (Senge, 2004).

According to Senge, team learning enables an organization to improve its ability to solve problems by seeking accessibility to expertise and knowledge buffers. An interrogative that rises here is how an organization can evaluate team learning.

Senge responds by arguing out that a learning organization possesses clearly defined structures that encourage openness besides persuading them to engage in dialogue and in open discussions (Senge, 2004).

The focus of any learning and development measurement criteria is based on evaluation of the structures of knowledge management, structures of knowledge creation, procedures and the processes of acquisition of knowledge, and the process of knowledge implementation at an individual and organizational level.

Strengths and weakness of Senge’s model

The model proposed by Senge has profound strengths. Nevertheless, some weakness may be pointed out. Some of the major strengths of the model include its ability to encourage maintenance of high levels of organizational creativity and competitive advantage.

Besides, it enables organizations to be well placed to handle external pressures that my affect negatively the performance of an organization and improvement of the quality of organizational outputs (Fulmer, Keys & Bernard, 1998). One of the major weaknesses is that the model does not provide the mechanisms of prevention or dealing with negative learning.

Indeed, according to Bontis and Serenko (2009), organizations often encounter the challenge of resistance to learning especially when some employees consider learning a threat to their status quo (p.281). This truncates into possession of mindsets that are closed with such employees failing to engage proactively with mental models as discussed by Senge.

Kim (2007) points out a major weakness of the model by claiming that some organizations find it hard to accept personal mastery since the concept possesses benefits that are intangible and hard to quantify (p.39). Personal mastery may also emerge as a major challenge to an organization.

Senge admits this weakness by informing that attempts to empower people who are misaligned in an organization may be counterproductive (Fulmer, Keys & Bernard, 1998). This implies that, in case people do not actively take part in the shared vision of an organization, personal mastery may have the repercussion of encouraging people to explore personal visions, which are not productive for an organization.

Applicability of the Model

All organizations value the contribution of human resource towards the creation of an enabled workforce. This means that any model, which seeks to provide human resource personnel with tools for assessment and evaluation of the impacts of learning programs, would be welcomed warmly across all organizations in all industries.

However, Senge’s learning model emphasizes the creating of an enabling environment for employees to take part in the formation of a common shared vision of an organization. It is only in a democratic and decentralized organization where employees’ voice count (Kim, 2007). In such an organization, a whole is visualized as one that comprises a number of different components.

This means that the model is inappropriate in an organization, which perceives a whole as bigger than parts. Such organizations are bureaucratic. They follow the traditional management structures that hinder knowledge sharing, which is central to the success of Senge’s model.

Revision and Possible Changes to the Model

The model for organizational learning and development postulated by Senge discusses training as an essential component of enhancing learning.

However, it does not give details of how evaluation may be done to determine the effectiveness of training and development programs. Thus, it is necessary to include a change such as inclusion of mechanism of determination of the reaction of people subjected to various training programs.

The primary aim of the reaction is to measure how participants in a training program respond. Kim (2007) argues that reaction to the training program should be done immediately a program is introduced. The main aspects measured are the attitudes of the trainees on various elements of training programs, perception of the instructors, methods of presentation of training topics, and audiovisual perspectives of learning programs.

I propose questionnaire as the main tool for measurement of the reactions of trainees. The principal goal of this level is to enhance the overall satisfaction of all people incorporated in the organizational learning process.

Training outcomes are unrealizable without possession of positive attitudes of the participants in the learning process. This reason underlines the purpose of evaluation of reactions of the people to training programs.

Having information on the reactions of employees to the training programs enables trainers and managers to eliminate all programs, which are unpopular in terms of rendering positive impacts on the performance of people within an organization.

Assessment of the reaction of employees also gives a room for determination of the elements of training programs, which need improvement so that an organization can have a more elaborate and effective learning and development program while integrated within the model postulated by Senge.

How Organizations can use the Model

Learning and development evaluation program needs to have clearly defined objectives. This forms the standards to which the evaluator examines the extent of achievement of the goals of learning and training programs. Based on Senge’s model, four main areas for evaluation are learning, reaction of employees to learning programs, behavior, and results.

Reaction seeks to identify the perception of people about a certain learning experience. Possible tools for use include post-learning surveys and/or verbal questionnaires. This approach is practical since it is easy and quick to conduct without encountering heavy costs related to analysis of data.

Learning is the actual measurement of the knowledge transferred to the individual and work teams. Important tools include interview, observations, assessments, and even tests before and after running a given learning program. Applying Senge’s model to evaluate behavior entails determination of the threshold to which workers plough the knowledge learnt back into the job through implementation.

Observation of changes in performance and assessment of the emphasis of people to do things in different ways than before may help in the determination of personal mastery (Bontis & Serenko, 2009). Unfortunately, this outcome demands immense cooperation among all line managers.

Finally, learning and development program must produce results. Consequently, it is crucial to evaluate the impact of learning and training program on both the organizational environment and the business. This deliverable can be tracked through performance and reporting systems deployed by an organization.

Reference List

Bontis , N., Crossan, M., & Hulland, J. (2002). Managing an Organizational Learning System by Aligning Stocks and Flows. Journal of Management Studies, 39(4), 437–469.

Bontis, N., & Serenko, A. (2009). Longitudinal knowledge strategizing in a long-term healthcare organization. International Journal of Technology Management, 47(3), 276–297.

Easterby-Smith, M., Crossan, M., & Nicolini, D. (2005). Organizational learning: debates past, present and future. Journal of Management Studies, 37(6), 783-796.

Fulmer, R., Keys, J., & Bernard, M. (1998). A Conversation with Peter Senge: New Developments in Organizational Learning. Organizational Dynamics, 27(2), 33-42.

Kim, D. (2007). The Link between Individual and Organizational Learning. Sloan Management Review, 2(1): 37–50.

Mants, J. (2003). Two basic mechanisms for organizational learning in schools. European Journal of Teacher Education, 26(3), 293–311.

McHugh, D., Groves, D., & Alker, A. (2008). Managing learning: what do we learn from a learning organization? The Learning Organization, 5(5), 209-220.

Senge, P (2004). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday.