Introduction

The development of joint replacement surgery was a major milestone in orthopedic surgery. Hip replacement is often the only viable solution for patients with advanced joint deterioration. Total hip arthroplasty is usually the last recourse for patients whose condition cannot be resolved clinically.

Successful hip replacement usually leads to a better quality of life for the patient, due to the elimination of pain, and restoration of mobility. In addition, hip replacement improves the overall functioning of the body.

The most common medical condition that can lead to the need for hip replacement is osteoarthritis. Other conditions include inflammatory arthritis, fracture, dysplasia, and malignancy.

The use of Metal-on-Metal hip replacement implants arose from the need to have durable implants. Metals also offered biomedical engineers a wide range of possibilities when designing Metal-on-Metal hip implants. Apart from durability, biomedical engineers could treat metals to make them inert, and to make them withstand corrosion better that most materials.

Materials and Design

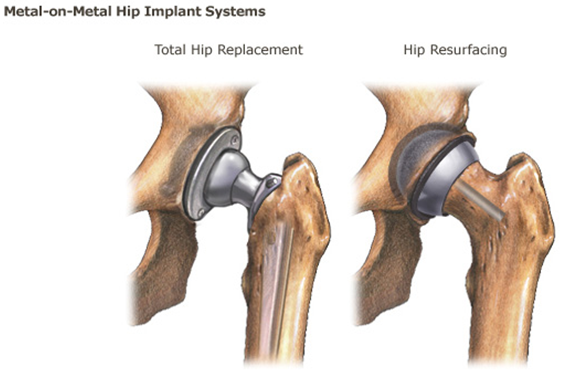

There are two types of Metal-on-Metal hip replacement systems. The first type is the total hip replacement system. Total hip replacement involves the substitution of the hipbone and the hip joint with a metallic system as shown in Figure 1 below.

The second type of hip implant is used in cases where the hipbone is not very damaged, by where the hip joint has deteriorated. In this case, a replacement hip joint substitutes the lining of the hip joint in the place of worn out cartilage as shown in Figure 1 below.

Four main types of hip replacements are available to patients. The first type is the Metal-on-Plastic implant. Usually, this type of implant is made using a polyethylene socket, while the bearing is made from cobalt-chrome alloy. The second type of hip implant is the Metal-on-Metal implant made from cobalt-chromium alloy, titanium alloy, or sometimes stainless steel.Figure 1: Metal-on-Metal Hip Implant Systems

The third type of implant is the Ceramic-on-Ceramic implant. This type of implant has the best durability because of the resistant nature of ceramics. The debris produced as the joint wears is also not toxic to the human body. The fourth type of implant is the Ceramic-on-Polyethylene implant. This type combines the qualities of the two materials to produce a very durable implant.

Table 1 below compares devices from different manufacturers.

Table 1: Device Comparison.

Clinical Safety and Efficacy

A team of researchers at the Joint Replacement Institute of the Orthopedic Hospital in Los Angeles conducted a study to investigate the performance of Metal-on-Metal hip replacement implants. The study was titled “Metal-on-Metal Hybrid Surface Arthroplasty: Two to Six-Year Follow-up Study”. It was published by Amstutz et al. in 2004 in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

The researchers studied the performance of 400 Metal-on-Metal hip replacements in 355 patients who had undergone arthroplasty after an average of three and a half years. The reviews were done three months after the arthroplasty, and then annually for a period of three years.

The findings from the study were as follows. First, the researchers found that most of the patients were able to resume active lifestyles after the arthroplasty, including participating in sporting activities. The level of activity of each patient dictated the rate of wear of the replacement joints.

Out of the 400 hip arthroplasty procedures, twelve (3%) required total replacement after four years due to loosening of the femoral component, or due to neck fractures on the femoral component. The main risk factors associated with the degradation of the femoral component were large femoral heads, female gender, patient height, and small component size in male patients.

The researchers concluded that in the overall sense, their review of the performance of Metal-on-Metal arthroplasty gave an encouraging picture. Secondly, the researchers concluded that optimal femoral preparation was a key success factor in hybrid Metal-on-Metal arthroplasty.

In addition, optimal sizing of the replacement joint was also necessary for successful operation of a replacement hip. The researchers also concluded that replacing a Metal-on-Metal joint by a standard femoral component is easy to carry out.

This research project supported the continued use of Metal-on-Metal hybrid joints based on their durability. The researchers failed to take into account the impact of the metallic debris on periprosthetic tissue. This shows that the researchers were biased towards the performance of the Metal-on-Metal hybrid joints at component level.

Clarke et al. (2003) conducted research into the toxicological exposure to Chromium and Cobalt in patients who had undergone Metal-on-Metal hip arthroplasty. The researchers presented their findings in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery in an article titled, “Levels of Metal Ions after Small and Large Diameter Metal-on-Metal Hip Arthroplasty”.

The hypothesis of the project was that the production of arthroplasty debris would be less after resurfacing arthroplasty that after total hip arthroplasty. The patients chosen to participate in the research project were those who had undergone arthroplasty at least six months prior to the research. The inclusion criteria included having undergone either total hip arthroplasty or resurfacing arthroplasty.

The exclusion criteria include the presence of other metallic prosthesis in the body with the exception of titanium. In addition, the researchers excluded patients with secondary exposure to cobalt or chromium.

The researchers compared the levels of chromium and cobalt in two sets of 22 patients who had undergone resurfacing arthroplasty and those who has undergone total hip arthroplasty. The first finding was that patients who had undergone resurfacing arthroplasty had medium serum levels of cobalt and chromium of 38 nmol/l and 53 nmol/l.

These levels were much greater than the levels found in those who had undergone total hip arthroplasty, which were 22 nmol/l and 19 nmol/l respectively. This notwithstanding, the researchers noted that these levels were significantly greater than the levels in patients without implants, which is typically 5 nmol/l.

The researchers concluded that larger diameter implants result in greater exposure to cobalt and chromium. In addition, they concluded that patients have a higher level of metal ion concentrations after resurfacing arthroplasty compared to total hip arthroplasty.

The main criticism about this research project was that it focused too much on the impacts of the metal debris arising from hip arthroplasty. A balanced view of the subject should have included a cost-benefit analysis aimed at finding out whether this condition was better than the prognosis arising from hip problems. This way, it would have been easier to decide whether the risks are worth taking.

A study by researchers in South Korea sought to establish whether metal hypersensitivity had a role in the onset of osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty.

Park et al. (2005) conducted their research in the Departments of Orthopedic Surgery, Dermatology, and Pathology in the Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, located at the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea. They presented their findings in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery through an article titled, “Early Osteolysis Following Second-Generation Metal-on-Metal Hip Replacement”.

The researchers wanted to investigate the possible role of metal hypersensitivity in the etiology of osteolysis. Their research was motivated by the increasing use of Metal-on-Metal components for hip arthroplasty as a replacement for metal-on-polyethylene components, especially on second-generation patients. The researchers studied 165 patients (169 hips) who had undergone total hip arthroplasty between 2000 and 2002.

The researchers followed the patients for a period of twenty-four months. After this period, the researchers found that nine patients had developed osteolytic lesions. The researchers then conducted skin patch tests for hypersensitivity on the nine patients, and in a control group of nine patients who did not have the lesions.

The researchers also conducted further tests on two hips during replacement surgery. These tests included microbiological cultures, histopathologic examinations, and immunohistochemical analysis on the two hips.

The results obtained by the researchers showed that the patients who had developed osteolytic lesions had a higher hypersensitivity reaction to cobalt compared to their cohort. The two hips that underwent further tests showed no signs of metallic staining. There was however a high concentration of lymphocytes in the periprosthetic region.

The researchers failed to find a way of telling apart natural sensitivity to Cobalt from acquired hypersentivity. This leaves the research findings open to interpretation because there is no proof adduced to the heightened levels of cobalt in the bodies of patients. In the same way, the researchers failed to find out whether Metal-on-Metal prosthesis has anything to do with osteolysis. This reduces the overall efficacy of the report.

A research project conducted in the Departments of Orthopedics and Pathology, at the Klinikum der Universität Göttingen in Göttingen, Germany sought to find out whether there is evidence to support the presence of an immunological reaction in patients who undergo a successive arthroplasty using Metal-on-Metal implants.

The findings of the research project by Willart et al. (2005) were presented in the article titled “Metal-on-Metal Bearings and Hypersensitivity in Patients with Artificial Hip Joints”.

The initial observation by the researchers that triggered the research process was that the some patients experienced a recurrence of preoperative symptoms after undergoing a second-generation total hip arthroplasty.

Ideally, the surgery should have alleviated the entire range of symptoms related to aging prosthesis. In this regard, the researchers developed the project to find out why there was little or no change in patients who underwent arthroplasty involving second-generation Metal-on-Metal prosthesis.

The researchers collected clinical data and examined periprosthetic tissue from nineteen patients who underwent arthroplasty in participating clinics. The sample was chosen on a consecutive basis as an application of random sampling.

Out of the nineteen patients, fourteen patients received alumina-ceramic or metal-on-polyethylene implant. Five patients received second-generation Metal-on-Metal total joint replacement. The researchers used immunihistochemical methods to test the periprosthetic samples. They also used histological methods to test the samples.

The main findings that the researchers reported were that the patients who underwent Metal-on-Metal total hip replacement had a recurrence of the preoperative symptoms characterized by an immunological reaction.

The evidence adduced to support an immunological reaction was the presence of T and B lymphocyte cells in the periprosthetic region. In addition, immunohistochemical tests showed that the immunological reactions were ongoing as at the time of the test.

This project made very important findings in regards to the impact of metallic debris arising from Metal-on-Metal prosthesis. The researchers did not provide a conclusive proposal on how to deal with the issues. This leaves the readers with task of deciding what to do about the prosthesis. Good research reports need to take into account the likely range of actions.

Fisher et al. (2004) conducted a simulated experiment on the performance of surface engineered prosthesis to find out whether it is possible to reduce the rate to wear on metal-to-metal prosthesis. The researchers used a simulator to mimic the operating conditions of a Metal-on-Metal prosthesis. Lower rates of wear and tear associated with Metal-on-Metal prosthesis compared to other types of implants inspired the researchers.

Metal-on-Metal prostheses have much lower wear rates compared to polyethylene prostheses. However, the researchers were aware that the levels of toxicity of the residue associated with Metal-on-Metal prostheses were higher that the levels associated with residue from other materials.

Therefore, they identified the need for Metal-on-Metal prostheses with lower wear rates to eliminate or reduce the toxicity associated with metallic residue. The stated goals of the project were to investigate the wear, wear debris, and ion release of fully coated surface engineered Metal-on-Metal bearings for hip prostheses.

The researchers used the Leeds Mark II physiological hip joint simulator operating at 1 Hz to conduct the wear experiments. This enabled them to collect the debris from the exercise. The test units were five types of surface engineered prosthesis. The researchers also subjected conventional Metal-on-Metal prostheses to the simulator tests to develop a comparison.

They found that the surface engineered bearings had a wear rate that was at least 18 times lower than traditional prosthesis after one million cycles and 36 times lower after five million cycles.

The differences were calculated by measuring the debris levels and ion concentration in the lubricants. The debris levels and ion concentration in the lubricants were much lower when the experiments were done using surface engineered prostheses.

The experiment by Fisher shows that it is possible to reduce the wear rate of metallic prostheses. Theoretically, this should reduce the problems associated with high serum concentration of metallic ions in patients with Metal-on-Metal prosthesis. However, the researchers failed to find out whether better surface engineering can reduce the problems associated with immunological responses especially in periprosthetic tissue.

Conclusion

This review shows that in the period prior to 2005, there was increasing concern regarding the use of Metal-on-Metal implants because of the immunological reactions caused by hypersensitivity to high ion concentration. In addition, the long-term impact of high ion concentration is unknown. Surface engineering can help resolve these fears.

Reference List

Amstutz, HC, Beaule, PE, Dorey, FJ, LeDuff, MJ, Campbell, PA & Gruen, TA 2004, ‘Metal-on-Metal Hybrid Surface Arthroplasty: Two to Six-Year Follow-up Study’, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, vol 86, no. 1, pp. 28-39.

Bohle, P & Quinlan, M 2000, Managing Occupational Health and Safety: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Macmillan Educational AU, South Yarra.

Clarke, MT, Lee, PT, Arora, A & Villar, RN 2003, ‘Levels of Metal Ions after Small- and Large Diameter Metal-on-Metal Hip Arthroplasty’, The Journal of Joint and Bone Surgery, vol 85, no. 6, pp. 913-917.

FDA 2013, Medical Devices: Metal-on-Metal Hip Implants. Web.

Fisher, J, Hu, XQ, Stewart, TD, Williams, S, Tipper, JL, Ingham, E, Stone, MH, Davies, C, Hatto, P, Bolton, J, Riley, M, Hardaker, C, Issac, G & Berry, G 2004, ‘Wear of Surface Engineered Metal-on-Metal Hip Prostheses’, Journal of Material Science: Materials in Medicine, vol 15, no. 1, pp. 225-235.

Park, Y-S, Moon, Y-W, Lim, S-J, Yang, J-M, Ahn, G & Choi, Y-L 2005, ‘Early Osteolysis Following Second-Generation Metal-on-Metal Hip Replacement’, Journal of Joint and Bone Surgery, vol 87, no. 7, pp. 1515-1521.

Singh, J. A. 2011, ‘Epidemiology of Knee and Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review’, Open Orthopaedics Journal, vol 5, no. 1, pp. 80-85.

Willart, H-G, Buchhorn, GH, Fayyazi, A, Flury, R, Windler, M, Koster, G & Lohmann, CH 2005, ‘Metal-on-Metal Bearings and Hypersensitivity in Patients with Artificial Hip Joints’, Journal of Joint and Hip Surgery, vol 87, no. 1, pp. 28-36.