Introduction

Owing to rising medical costs, the quality-of-care provision in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has declined substantially in recent years. The increasing challenges of the healthcare systems related to the complexity of diseases and the advancement of treatment approaches necessitate integrating qualitatively new methods of care delivery. Some researchers have advocated using multidisciplinary healthcare teams (MDHTs) as an effective measure for continuously improving the care delivery process (Carney et al., 2019; Gomez et al., 2019; Parker et al., 2021). MDHTs refer to groups of healthcare providers wherein members with expertise in different areas collaborate to guide clinical decision-making (Fradgley et al., 2021). Indeed, Zajac et al. (2021) found that using MDHTs over traditional models of care was associated with improved decision-making and more effective execution of tasks. Moreover, in the context of the contemporary rapidly changing world, the focus on long-term outcomes for organizations and communities is essential for health care settings, which validates consolidation of interdisciplinary efforts (Joseph-Richard & McCray, 2022).

However, the effective utilization of MDHTs in the KSA is limited by the nation’s health systems in transition. Studies have confirmed that collaboration between care professionals is affected by institutional and environmental factors (Amgalan et al., 2021) that can aggravate pre-existing barriers (Wei et al., 2022) and thereby undermine the realization of common goals and objectives. Indeed, multiple research studies conducted to identify management-related issues in the implementation of MDHTs indicate that the ineffectiveness in the exchange of information and cooperation between the members of MDHTs is one of the most significant challenges (Abdi et al., 2015). Moreover, Andreatta (2010) and Molleman et al. (2010) identify another challenge in terms of managing MDHTs due to their distinction from non-health teams, which is why the implementation of conventional multidisciplinary teams frameworks requires additional processing and adaptation to meet the needs of the healthcare setting.

Furthermore, transitioning healthcare systems undergo transformational processes in terms of policy implementation and integration of new approaches, which only complicates the opportunities for effective functioning of MDHTs (O’Reilly et al., 2017). The internal healthcare team’s managerial issues, including absenteeism, dysfunctional workplace relationships, and limited awareness about the functioning of MDHTs, also serve as barriers to effective multidisciplinary care delivery (Jalil et al., 2013). Such obstacles identified in the contemporary healthcare system in the KSA inform the practice and research gap, contributing to the relevance of this research study. Therefore, Buljac-Samardzic et al. (2020) recommend strategically targeting these contingencies using MDHT training interventions to resolve issues and foster collaboration. The effectiveness of such an exercise will likely vary depending on the context.

Despite the availability of an extensive body of research literature on the managerial challenges of the MDHTs’ functioning and the perceived advantages of adhering to a multidisciplinary health care delivery system, there is a substantial research gap. Indeed, it is related to the lack of comprehensive and sufficient research on the particular needs of MDHTs development, and the ways training might benefit the quality and efficiency of care delivery. Accordingly, in this study, we examined the extent to which existing training interventions in the KSA are effective in eliminating barriers and promoting enablers to collaboration between members of MDHTs. In particular, this study’s central research question was: To what extent have existing training interventions for MDHTs, in the KSA been successful in diffusing barriers and promoting enablers to collaboration between healthcare professionals?

Literature Review

The context for the research was based on the results of a systematic review of the recently published scholarly studies on the management of healthcare teams. A large body of literature has been reviewed to identify pivotal themes in the current research on the topic of MDHTs. The pivotal role of MDHTs, the challenges for their effective functioning, and the importance of understanding their conceptualization and the need for training are most commonly addressed in the current literature.

The Importance of and Need for MDHTs

Research shows that the performance of individual specialists in isolation is less effective in tackling complex issues such as healthcare problems compared to a multifaceted, interdisciplinary approach. The adherence to teamwork in MDHTs allows for effective communication and interaction between the participants to improve patients’ quality of life through the delivery of timely, evidence-based care (Aguirre- Duarte, 2015). Moreover, the ineffectiveness or the lack of teamwork in the healthcare setting is manifested through the conventional approaches’ procedural and operational deficiencies (Breslin, 2022). Indeed, non-team-based approaches to health care delivery have been found to fail to meet the needs of critical care.

Indeed, the readmission of patients to different specialists without a specifically outlined procedure might apply to the cases of primary care diseases where immediate action is less required (Buckland, 2016). However, for the complicated cases when time efficiency is vitally important, and the decision-making should be fast and reliable, the lives and well-being of patients might be hindered due to the lack of impaired functioning of MDHTs (Abdulrahman, 2011).

MDHTs comprise healthcare providers with different areas of expertise who collaborate to guide the clinical decision-making process. This approach is widely accepted as the gold standard of care provision across a range of contexts (Lamprell et al., 2019; Morton et al., 2017) owing to multiple associated benefits such as reduced costs and enhanced patient outcomes (Zajac et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Taberna et al., 2020). In addition, the impairments in MDHT’s functioning as efficient units have been found to be a significant factor jeopardizing patient safety (Lorenzini et al., 2021). Indeed, workplace conflicts and non-synchronized collaboration migth hinder patient outcomes both in short- and long-term perspecitves.

Barriers to MDHTs’ Functioning

The success of MDHTs hinges upon effective collaboration between affiliated members that can be influenced by various barriers and enablers. Hatton et al. (2021), for example, identified members’ lack of knowledge, role confusion, poor interpersonal skills, excessive workload, and profession-specific goals and team hierarchy as impediments to collaboration; Duncan et al. (2020) and Maharaj et al. (2020) concurred. Similar findings have been introduced by other scholars who identified that non-technical skills, information exchange proficiency, and poor quality of interpersonal relationships between the specialists on a team serve as some of the most significant obstacles to effective MDHTs functioning (McNeil, Mitchell, & Parker, 2013; Weller et al., 2014). Conversely, Sørensen et al. (2018) observed standardized procedures for documenting and handling data, establishing local specialized MDHTs, and sharing knowledge to promote collaboration among interdisciplinary professionals.

Institutional and environmental factors also influence the success of the interdisciplinary collaboration. They represent the broader social context in which MDHTs are embedded and define the nature of the assigned tasks, allocated timeframe, and governance structure for the teams (Moirano et al., 2020). Such concerns are particularly pertinent for transitioning health systems rife with challenges, including poor teamwork, competency mismatches, and scarcity of qualified healthcare professionals (Amgalan et al., 2021). Moreover, the ambiguity and non-clarity of team member roles in interdisciplinary collaborations in healthcare settings serve as barriers to achieving equity for patient care (Carey & Taylor, 2021). Several studies have further advocated using interprofessional education (IPE) to empower healthcare professionals and students to work in MDHTs (Homeyer et al., 2018; Guraya & Barr, 2018; Reed et al., 2021). Documented advantages of IPE include increased mutual respect, improved understanding of professional roles, effective communication, and better patient outcomes (Homeyer et al., 2018).

Training of MDHTs

Given the importance of MDHTs and the barriers to their adequate implementation, the need for effective MDHT training is justified. Unique training interventions can be modeled in line with IPE principles to encourage collaboration between care professionals in MDHTs (Miller et al., 2019). Notably, healthcare organizations are characterized by hyper-complexity, steep hierarchies, time pressure, high task interdependence, and involvement of multiple decision-makers, giving rise to stress and fatigue that can compromise team outcomes (Salas et al., 2018). Training interventions, including simulation courses, interactive workshops, team debriefing, assessments, facilitated discussions, presentations, role-playing, and communication seminars, can assist team members in navigating the complex environment of healthcare institutions (Buljac-Samardzic et al., 2020). Training interventions for MDHTs can therefore play an important role in enhancing care provision at healthcare facilities via a wide range of pathways.

The use of MDHTs in transitioning health systems is crucial, as it has been noted to optimize care delivery, reduce waste and burden on the system, and ensure sustainability (Braithwaite et al., 2018). Moreover, there is a significant need for training communication skills in interdisciplinary teams ofg hyealthcare workjers in agreements with the requirements of their department’s speciality due to the core relevance of good communication capabilities of professionals to the quality and efficiency of their services (Nieuwoudt et al., 2021). Advantages linked with the use of multidisciplinary training interventions include improvements in individual and team performance, clinical and non-technical knowledge, mutual respect, situational awareness, communication, job satisfaction, organizational learning, hospital transition, and timeliness and deterioration in autonomous cultural attitudes and perceptions of inadequate staffing levels (Buljac-Samardzic et al., 2020).

Health systems in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) are currently under transition following the introduction of strategic reforms to address rising costs of care and population growth (Rahman & Alsharqi, 2018), offering a rich context to examine collaboration-related concerns associated with MDHTs. Furthermore, since the quality-of-care provision in the Kingdom is dwindling (Alatawi et al., 2020), it is also possible to determine if multidisciplinary training interventions can improve collaboration and patient outcomes. The current study investigates these concerns to identify pathways for ameliorating the Saudi Health System using a qualitative research design to conduct semi-structured interviews.

The Socio-Institutional Theory

The theoretical framework for the conducted study is the socio-institutional theory. It holds that for the adequate functioning of an organization, its stakeholders should be treated as influential and legitimate participants whose operational and social contributions are valued (Scott, 1995). The pivotal consideration within this theory is the idea that organizations should be structured and managed from the perspective of their functioning as social units (Scott, 2008). This theoretical approach allows for shifting from the mere rationalization of the actions to the emphasis on inter-personal interactions, legitimate practices, resilience, and productive cooperation (Scott, 1995). Ultimately, the use of this theory allows for justifying the importance of non-technical skills, communication competencies, and teamwork proficiency training as the most effective issues in MDHTs development.

Conceptual Model

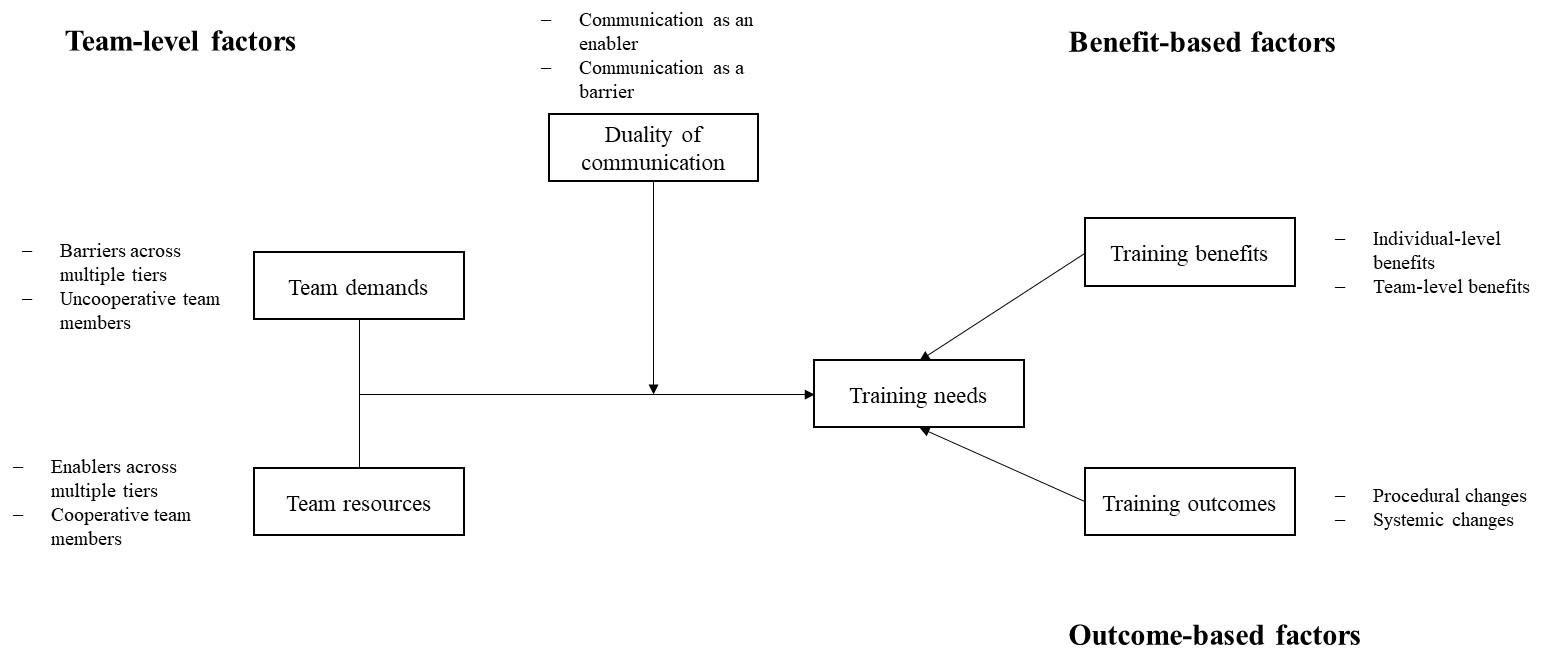

The conceptual model for the conducted study is presented in Figure 1. It incorporates the multiple factors predetermining the necessity of training for healthcare teams to improve interdisciplinary benefits. The first level of factors is the team level, which includes team demands and team resources, which influence the opportunity for training and ultimate change. The second level of factors includes benefits, which are anticipated for both individual team members and whole teams. Finally, the third level of factors influencing training needs is the outcome-based factors, which include changes to procedures and systems. The changes might be obtained through the overcoming of the duality of communication.

Methodology

Study Design

This study adopted an exploratory qualitative design; its methodology employed the consolidated criteria checklist for reporting qualitative research by Tong et al. (2007). Qualitative exploration is suitable for examining under-researched topics such as the effectiveness of extant training interventions for MDHTs in the KSA (Fox et al., 2018). The approach further supports data collection using semi-structured interviews to identify prominent barriers and enablers to collaboration between members of MDHTs.

Setting and Participants

Three KSA healthcare institutions (hospitals) were selected as research sites. The institutions were chosen to inform insight into the differences between hospitals of varying sizes (70 beds, 500 beds, and 1000 beds) and from distinct regions in the Kingdom. Participant recruitment was performed using a purposive sampling strategy; qualitative research is predicated upon selecting the most appropriate respondents who can provide an in-depth understanding of the investigated phenomenon (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). A letter elaborating the study scope and purpose and requesting participation was sent to the human resource departments of the research sites. A total of 50 respondents were shortlisted as the sample pool based on their involvement in MDHTs for no less than six months. The authors attempted to balance different professions; however, allied health professionals were overrepresented due to limited staff availability.

Data Collection

Data was gathered using one-on-one semi-structured interviews that lasted for about one hour each to ensure sufficient depth and breadth of information. A checklist of semi-structured questions was used as a guide to prompt discussions while permitting the respondents to present queries, seek clarification, and/or offer in-depth reflections. The topics covered in the guide included common enablers and barriers to collaboration between members of MDHTs and the participants’ evaluation of the effectiveness of existing training interventions. All interviews were conducted over videoconferencing apps. Informed consent was verbally obtained from the respondents before beginning the interviews. The interviews were digitally recorded with the participants’ permission.

Data Analysis

The digital recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was undertaken to detect patterns of meaning across the dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Firstly, the transcripts were reread alongside the video recording to verify accuracy. This method of data analysis allowed for researchers’ familiarization with the data. Following rereading, the transcripts were coded using a cumulative process that determined trends in accordance with the emerging themes rather than assessing the data’s conformity to literature (Collis & Hussey, 2003). The codes were interpreted to identify themes pertinent to different dimensions of MDHTs. Thus, the themes were compared with each other to detect commonalities and typical features. Topics were derived for each theme as contributing factors based on the data coding results. Lastly, the transcripts were segregated across the categories of positive, neutral, and negative to ascertain the potential for adaptive change in the Saudi Health System within the MDHT context.

Ethical Considerations

The study was performed in conformity to the principles of informed consent, data confidentiality, and participant anonymity. Respondents also had the right to withdraw consent at any point in the study. Approval for the study design was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Newcastle. The authors additionally completed a course in conducting clinical trials with human participants at the request of the study sites. No conflicts of interest were reported as the study was funded by the Saudi government.

Findings

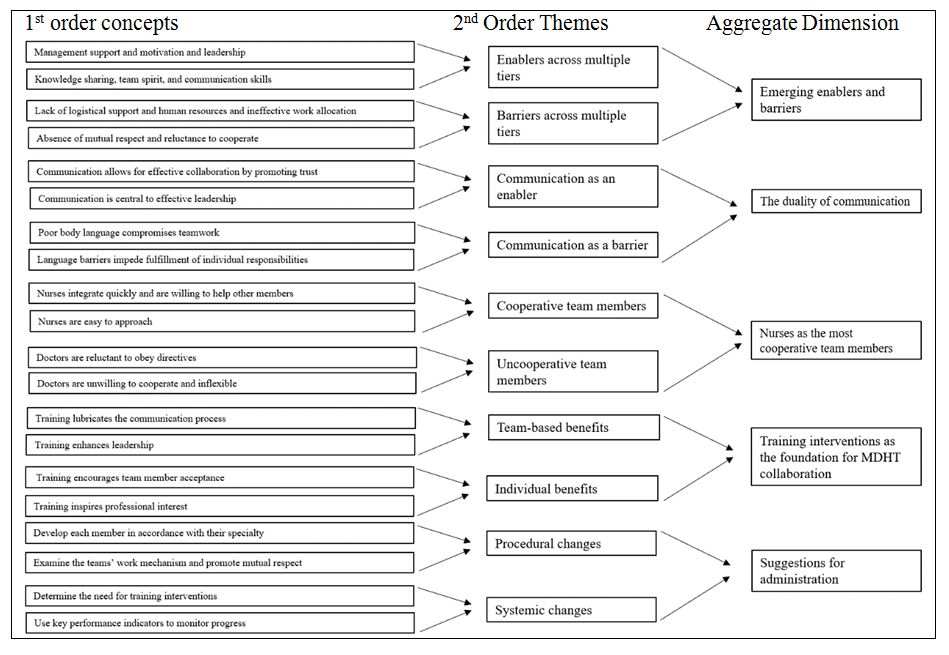

Table 1: Data coding process

Emerging Enablers and Barriers

The participants identified a broad range of barriers and enablers that facilitated/impeded collaboration in MDHTs. Role commitment, competence flexibility, work appreciation, sense of responsibility, team spirit and unity, management support and motivation, and rewards and incentives were among the prominent enablers. On the other hand, lack of dedication, differences in opinion, role confusion, shortage of human resources and other utilities, and language-related difficulties comprised the common barriers. In particular, leadership was recognized as a salient determinant of MDHT collaboration success, whereas lack of mutual respect was deemed to frequently impede teamwork.

The leader is the first enabler; the leader has to be liked and accepted, with good communication, and knows how to deal with employees. From my experience with teams, I think the leader is the one who creates an enjoyable working atmosphere.

The majority of the respondents considered the leader to be the essential team member responsible for fostering a spirit of unity, engaging other members, resolving disputes, and supporting positivity. Conversely, lack of mutual respect was regarded as being responsible for delays in care provision, conflicts between members, and team failure.

Mutual respect has an impact on the personality of the members, especially since the emergency department staff all work under pressure and it is required to complete the required work at a specific time. Sometimes when a person is under pressure, he may lose patience, and this is reflected in his personality and the way he treats the other members.

Overall, collaboration enablers and barriers were linked with several outcomes pertaining to motivation, adherence to protocols, team culture, and team productivity.

The Duality of Communication

Communication was categorized as both an enabler and a barrier. Participants reflected upon the influence of different aspects of communication, including non-verbal cues and language proficiency, on collaboration between MDHT members. Concerning its enabling effect, communication was noted to facilitate information exchange, establish common grounds, and determine team productivity. However, ineffective or abusive communication was associated with impaired decision-making and compromised teamwork.

Indeed, communication is the most important thing. When a person is inflexible, does not accept anyone’s opinion and adheres to his opinion only, does not listen to others, does not change anything, says I am like this, and I will stay like this, and does not make any effort to change, this certainly affects and impedes the work of all the team.

Among the skills and competencies central to MDHT collaboration, the participants considered communication to be more significant than factors such as knowledge and creativity. The respondents suggested that effective communication skills diffused barriers to collaboration, such as lack of mutual respect and adherence to appointment schedules, and allowed team members to capitalize upon their strengths.

Taking courses in communication skills, that is, how to communicate effectively, how to say the important thing at the right time, how not to distract my teammates, when to speak and when to be silent.

Moreover, they confirmed that competent team leaders were always good communicators who employed their skills to navigate complex interactions and define team priorities. Communication remained an overarching theme in most participant responses to different queries, emphasizing its centrality to the research question.

Nurses as the Most Cooperative Team Members

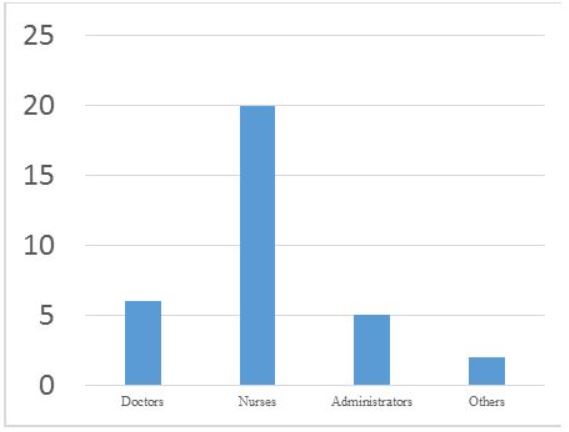

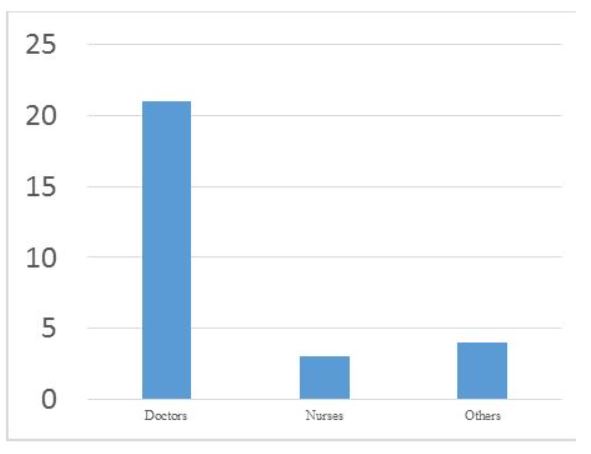

Regarding professional groups’ willingness to collaborate, the participants shared two different opinions. Some perceived no difference between members with varying specialties, contending that all professionals, regardless of their backgrounds and experiences, made similar sacrifices and remained dedicated to team success. However, the majority of the respondents viewed nurses as the most cooperative team members (Figure 1). This group identified nursing professionals as more flexible performers who could seamlessly integrate into the team. They considered doctors to be the least cooperative group who often considered themselves superior to others and had difficulty following recommendations (Figure 2).

I mean, nurses are very effective with any team they work in. On the other hand, doctors they less flexible than others. Their participation is usually less effective than others within the teams. Doctors may have a higher sense of responsibility due to the high level of workload they have to manage.

According to the respondents, the involvement of different professional groups was crucial for determining team success. Nurses were more likely than any other professionals to display competence and flexibility by covering for the shortcomings of other members.

The professional group that has the desire and ability to work more is the nurses’ group. They are the crucial factor for achieving success in any team they are in.

In contrast, the participants confirmed that doctors often depended on others and refused to accommodate any divergent opinions. Overall, doctors were considered good at pertinent professional knowledge but poor in people management skills.

Training Interventions as the Foundation of MDHT Collaboration

Majority of the respondents related training interventions with a range of benefits that directly or indirectly supported MDHT collaboration. Following participation in training programs, progress was registered across the domains of individual skills, willingness to change, professional obligations, innovation, communication, attitudes, critical thinking, personal and professional boundaries, and team organization. Participants offered insight into strategic guidelines for implementing training interventions. For example, they considered training the team leader more important than training other members. Moreover, the respondents perceived merit in gearing the interventions for each member to address shortcomings and foster strengths on a case-by-case basis.

Training is very important. Anyone without training will not achieve anything and may be more of an obstacle than an achievement because the medical field is rapidly changing and modernizing.

The respondents acknowledged having participated in various training interventions and certification programs dedicated to Training of Trainers (ToT), working in MDHTs, skills development, communication improvement, and team leadership. Training interventions were generally regarded positively by the participants in the context of MDHT collaboration. Some respondents suggested that the success of training largely depended on members’ willingness to improve, and mere participation could not guarantee positive outcomes.

Suggestions for Hospital Administration

The participants put forth numerous recommendations for consideration by the hospital administration in a bid to improve collaboration between members of MDHTs. They urged the establishment of supportive leadership practices whereby all members are treated fairly and disputes amicably resolved. The significance of motivating members via different tactics, including financial incentives, was acknowledged as well. Respondents clarified that it fell upon the administration to inform individual members about their responsibilities and the value of teamwork before commencing operations. Furthermore, the participants’ advocated for routine implementation of training interventions that targeted individual members’ expertise.

Explanation and good understanding should be provided to each team member about what the team is, the importance of the team, what specialties are within the team, and each member’s role in the specialty; all of these things should be explained as policies.

Several respondents highlighted the administration’s duty to monitor improvements in the communication skills of their employees, clarify professional boundaries and responsibilities, and examine the team’s operating mechanisms. Lastly, the participants suggested formulating key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess competition between different members and monitor progress and achievement. These initiatives were meant to help team members become confident working as a group.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to identify the extent to which the modern training of MDHTs succeeds in overcoming barriers and improving healthcare delivery in the KSA. Through the qualitative semi-structured interview method, the study found that there were five commonly observed themes retrieved from the data collected from participants. In particular, they included identification of the emerging barriers and enablers, the duality of communication, nurses as the most cooperative team members regarding professional groups’ willingness to collaborate, the participant’s training interventions as the foundation of MDHT collaboration, and the suggestions for hospital administration. Pertaining to the research question, the study found that the implementation of the training programs and interventions is successful in tackling particular barriers to MDHT performance. However, more advanced and proactive practices should be introduced to ensure systematic and sustainable improvement as a result of training.

In the Saudi Health System, effective leadership functions as the most salient enabler of collaboration between members of MDHTs, while lack of mutual respect represents the central barrier to effective teamwork. Numerous training interventions have successfully facilitated MDHT collaboration by supplementing enablers and diffusing barriers. In particular, programs dedicated to improvements in, among others, communication skills have yielded multiple positive outcomes across the domains of team members’ attitudes, willingness to collaborate, information exchange, and productivity. Healthcare professionals from diverse specialties view training interventions positively. Nurses are predominantly regarded as the most cooperative team members and must therefore be considered for leadership roles. In contrast, doctors present the greatest difficulties while working in MDHTs. It is crucial that communication-based training interventions targeting doctors be implemented by the hospital administration to enhance affiliated members’ respect for different professionals and compliance with working mechanisms. Nevertheless, participation in such initiatives does not guarantee success, and, accordingly, the administration must deploy proactive measures to routinely monitor progress using KPIs.

This study drew upon the perspectives of diverse healthcare professionals working in the Saudi health system. Coupled with the considerable sample size, the findings of the present research are generalizable in the context of the Kingdom. However, the interpretation of the self-reported data was subject to researchers’ bias, which could have undermined the study’s internal validity.

Conclusion

Members in MDHTs face various challenges that are part-and-parcel of working in teams. The hospital administration must attempt to capitalize upon the strengths of individual members to diffuse potential contingencies. Due to their higher affinity for assimilation, nurses should be encouraged to participate in leadership-based training interventions. On the other hand, due to their reluctance to cooperate with other professionals, doctors should be enrolled in programs that target developing communication skills. Training interventions offer much utility in promoting enablers and diffusing barriers to collaboration in MDHTs. It falls onto the administration to judiciously utilize such measures for improving teamwork. The results of this study can be used to guide policy formulation in health institutions across the Kingdom. They also reveal key opportunities for improvement and highlight avenues that require informed consideration.

References

Abdi, Z., Delgoshaei, B., Ravaghi, H., Abbasi, M., & Heyrani, A. (2015). The culture of patient safety in an Iranian intensive care unit.Journal of Nursing Management, 23(3), 333-345. Web.

Abdulrahman, G. (2011). The effect of multidisciplinary team care on cancer management.Pan African Medical Journal, 9, 20. Web.

Aguirre-Duarte, N. A. (2015). Increasing collaboration between health professionals. Clues and challenges. Colombia Médica, 46(2), 66-70.

Alatawi, A., Niessen, L., & Khan, J. (2020). Efficiency evaluation of public hospitals in Saudi Arabia: An application of data envelopment analysis.BMJ Open, 10(1), e031924. Web.

Amgalan, N., Shin, J., Lee, S., Badamdorj, O., Ravjir, O., & Yoon, H. (2021). The socio-economic transition and health professions education in Mongolia: A qualitative study.Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 19(1). Web.

Andreatta, P. B. (2010). A typology for health care teams.Health Care Management Review, 35(4), 345-354. Web.

Buckland, D. (2016). Role of primary care in the management of cancer patients.Prescriber, 27(4), 45-49. Web.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. Web.

Braithwaite, J., Mannion, R., Matsuyama, Y., Shekelle, P., Whittaker, S., & Al-Adawi, S. et al. (2018). The future of health systems to 2030: A roadmap for global progress and sustainability.International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 30(10), 823-831. Web.

Breslin, D. (2022). When relationships get in the way: The emergence and persistence of care routines [Article; Early Access]. Organization Studies, 22, 01708406211053227. Web.

Buljac-Samardzic, M., Doekhie, K., & van Wijngaarden, J. (2020). Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade.Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 2-43. Web.

Carey, M. J., & Taylor, M. (2021). The impact of interprofessional practice models on health service inequity: an integrative systematic review.Journal of Health Organization and Management, 35(6), 682-700. Web.

Carney, P., Thayer, E., Palmer, R., Galper, A., Zierler, B., & Eiff, M. (2019). The benefits of interprofessional learning and teamwork in primary care ambulatory training settings.Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 15, 119-126. Web.

Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2003). Business Research. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke.

Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design : Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Davis, M., Luu, B., Raj, S., Abu-Ghname, A., & Buchanan, E. (2021). Multidisciplinary care in surgery: Are team-based interventions cost-effective?. The Surgeon, 19(1), 49-60. Web.

Duncan, P., Ridd, M., McCahon, D., Guthrie, B., & Cabral, C. (2020). Barriers and enablers to collaborative working between GPs and pharmacists: A qualitative interview study.British Journal of General Practice, 70(692), e155-e163. Web.

Fox, A., Bacile, T., Nakhata, C., & Weible, A. (2018). Selfie-marketing: Exploring narcissism and self-concept in visual user-generated content on social media.Journal of Consumer Marketing, 35(1), 11-21. Web.

Fradgley, E., Booth, K., Paul, C., Zdenkowski, N., & Rankin, N. (2021). Facilitating high quality cancer care: A qualitative study of Australian chairpersons’ perspectives on multidisciplinary team meetings.Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 3429-3439. Web.

Gomez, F., Curcio, C., Brennan-Olsen, S., Boersma, D., Phu, S., & Vogrin, S. et al. (2019). Effects of the falls and fractures clinic as an integrated multidisciplinary model of care in Australia: A pre–post study.BMJ Open, 9(7), e027013. Web.

Guraya, S., & Barr, H. (2018). The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis.The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(3), 160-165. Web.

Hatton, K., Bhattacharya, D., Scott, S., & Wright, D. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to pharmacists integrating into the ward-based multidisciplinary team: A systematic review and meta-synthesis.Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 17(11), 1923-1936. Web.

Homeyer, S., Hoffmann, W., Hingst, P., Oppermann, R., & Dreier-Wolfgramm, A. (2018). Effects of interprofessional education for medical and nursing students: enablers, barriers and expectations for optimizing future interprofessional collaboration – a qualitative study.BMC Nursing, 17(1). Web.

Jalil, R., Ahmed, M., Green, J. S., & Sevdalis, N. (2013). Factors that can make an impact on decision-making and decision implementation in cancer multidisciplinary teams: an interview study of the provider perspective. International journal of surgery, 11(5), 389-394.

Joseph-Richard, P., & McCray, J. (2022). Evaluating leadership development in a changing world? Alternative models and approaches for healthcare organisations [Article]. Human Resource Development International. Web.

Lamprell, K., Arnolda, G., Delaney, G., Liauw, W., & Braithwaite, J. (2019). The challenge of putting principles into practice: Resource tensions and real‐world constraints in multidisciplinary oncology team meetings.Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15, 199-207. Web.

Lorenzini, E., Oelke, N. D., & Marck, P. B. (2021). Safety culture in healthcare: mixed method study. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 35(8), 1080-1097. Web.

Maharaj, A., Evans, S., Zalcberg, J., Ioannou, L., Graco, M., & Croagh, D. et al. (2020). Barriers and enablers to the implementation of multidisciplinary team meetings: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework.BMJ Quality &Amp; Safety, 30(10), 792-803. Web.

McNeil, K. A., Mitchell, R. J., & Parker, V. (2013). Interprofessional practice and professional identity threat. Health Sociology Review, 22(3), 291-307.

Miller, R., Scherpbier, N., van Amsterdam, L., Guedes, V., & Pype, P. (2019). Inter-professional education and primary care: EFPC position paper.Primary Health Care Research & Development, 20, e138-e148. Web.

Moirano, R., Sánchez, M., & Štěpánek, L. (2020). Creative interdisciplinary collaboration: A systematic literature review.Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100626. Web.

Molleman, E., Broekhuis, M., Stoffels, R., & Jaspers, F. (2010). Complexity of health care needs and interactions in multidisciplinary medical teams. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 55-76. Web.

Morton, G., Masters, J., & Cowburn, P. (2017). Multidisciplinary team approach to heart failure management.Heart, 104(16), 1376-1382. Web.

Nieuwoudt, L., Hutchinson, A., & Nicholson, P. (2021). Pre-registration nursing and occupational therapy students’ experience of interprofessional simulation training designed to develop communication and team-work skills: A mixed methods study.Nurse Education in Practice, 53. Web.

O’Reilly, P., Lee, S. H., O’Sullivan, M., Cullen, W., Kennedy, C., & MacFarlane, A. (2017). Assessing the facilitators and barriers of interdisciplinary team working in primary care using normalisation process theory: An integrative review. PloS One, 12(5), e0177026

Parker, A., Brigham, E., Connolly, B., McPeake, J., Agranovich, A., & Kenes, M. et al. (2021). Addressing the post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A multidisciplinary model of care.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 9(11), 1328-1341. Web.

Rahman, R., & Alsharqi, O. (2018). What drove the health system reforms in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? An analysis.The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), 100-110. Web.

Reed, K., Reed, B., Bailey, J., Beattie, K., Lynch, E., & Thompson, J. et al. (2021). Interprofessional education in the rural environment to enhance multidisciplinary care in future practice: Breaking down silos in tertiary health education. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 29(2), 127-136. Web.

Salas, E., Zajac, S., & Marlow, S. (2018). Transforming health care one team at a time: Ten observations and the trail ahead.Group &Amp; Organization Management, 43(3), 357-381. Web.

Scott, W. R. (2008). Lords of the dance: Professionals as institutional agents. Organization Studies, 29(2), 219-238.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Sage Publications.

Sørensen, M., Stenberg, U., & Garnweidner-Holme, L. (2018). A scoping review of facilitators of multi-professional collaboration in primary care.International Journal of Integrated Care, 18(3), 13. Web.

Taberna, M., Gil Moncayo, F., Jané-Salas, E., Antonio, M., Arribas, L., & Vilajosana, E. et al. (2020). The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and quality of care.Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 85-101. Web.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357. Web.

Wei, H., Horns, P., Sears, S., Huang, K., Smith, C., & Wei, T. (2022). A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews about interprofessional collaboration: Facilitators, barriers, and outcomes.Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1-15. Web.

Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149-154.

Zajac, S., Woods, A., Tannenbaum, S., Salas, E., & Holladay, C. (2021). Overcoming challenges to teamwork in healthcare: A team effectiveness framework and evidence-based guidance. Frontiers in Communication, 6.