Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the hypothesis that the facial expression depicted by people is related to the effective emotional response. This study involves two experiments designed as a correctional alternative to the earlier versions that were associated with ambiguities.

The first experiment focuses on the efficiency of the procedures used for this experiment. Cartoons were used and the level of amusement measured under both the facilitating conditions and inhibiting conditions.

The second experiment further validated the method used and was used to answer some of the important questions that had not been answered in the previous experiments.

The findings propose that the effective response to a stimulus intensifies with the facilitation and softening of an expression.

Introduction

The influence of facial muscular activity has been the concentration of most research studies conducted regarding facial physiological responses. Most of these studies are based on the hypothetical theory forwarded by Darwin.

In this theory, it is suggested when an individual is stimulated, his or her emotional response can either be reinforced or attenuated.

However, this largely depends on whether or not it comes along with proper muscular activities. This has formed the backbone of the current facial feedback hypothesis (Clark, & Isen, 1982).

Previous experiments conducted to investigate facial feedback hypothesis were done by making the participants portray facial expressions associated to specific emotions. These emotional responses were measured by attaching electrodes between the eyebrows of the participants.

However, this method has limitations, especially the ambiguities that tend to affect the outcome of the experiment (Ekman, Levenson, & Friesen, 1983).

For instance, the procedure followed for this experiment does not prevent the participants from understanding the fundamental purpose for the manipulation of the facial activities (Colby & Lanzetta, 1976).

As such, the results obtained are rather subjective and therefore, an outcome of situational demands. In most instances, cartoons were used and the level of amusement in the participants was measured by focusing on the muscular responses that causes them to either smile or frown.

As stated above, it was easier for the participant to understand the purpose for the experiment and therefore, comply with the expected outcome (Darwin, 1872).

In another experiment, there was no manipulation of the facial expressions portrayed by the participants in the experiment.

Participants were asked to do a modification of their normal emotional response to a particular stimulus during the suppression experiment (Higgins, Rholes, & Jones, 1977).

The exaggeration experiment, on the other hand, required that the participants portray the exact facial expressional that properly represented the emotions of the stimulus they were experiencing.

However, it is still evident that the experimental conditions did not allow participants to discriminate between physiological and cognitive mechanisms (Izard, 1977). As such, it is possible that recipients may have repressed their proper emotional response to the stimulus (Izard, 1977).

Also, it is possible that participants might have intentionally over-emphasized their emotions to produce the expected emotional expression. As a correctional response to the limitation in the earlier experiments, this study uses a different procedure that is clearer and has no ambiguities.

It does not depend on the generation of facial expression but rather focuses on the activation of appropriate muscles related to the expected emotional expression (Izard, 1981).

This, therefore, lowers the chances of the participant interpreting their muscular activities to a particular emotional response. The cognitive strategy to alter their emotion is thus prevented.

The study is based on the facial feedback hypothesis, which emphasizes that facial expressions provide proprioceptive, cutaneous, or vascular feedback to the expresser, which influences emotional experience.It is thus related to psycho-motor coordination (James, 1990).

More specifically, the main area of interest is in the individual’s capability to carry out various tasks with elements of their body not routinely utilized for such chores (Gavanski, 1986).

In this study, subjects are asked specifically to contract the facial muscles used to express emotions or are asked to perform non-emotional tasks that require contraction of these muscles.

The experimental study, in this case, investigates the capability to carry out similar chores using other parts not traditionally utilized for doing such chores.

The aim of this study was to investigate the hypothesis that the facial expression depicted by individuals has a direct relationship with the effective emotional response (Hager, 1982).

This study involves two experiments designed to respond to the earlier versions still associated with inconsistencies and vagueness.

The first experiment focuses on the efficiency of the procedures used. In essence, cartoons were used and the level of amusement measured under both the facilitating conditions and inhibiting conditions.

The second experiment further validated the method adopted and was used to answer some of the important questions that had not been catered for in the earlier experimental studies.

In a nutshell, this study hypothesizes that an individual’s facial activity influences his or her response (Leventhal & Mace, 1970).

Method

Participants

This investigation consisted of 101 people: 76 females and 25 males. Their ages ranged from 19 years to 49 years with a mean age of 21.74 years (SD = 3.825). Participants were recruited by students of the 2012 Developmental Psychology class from people known to them.

Demographic characteristics, such as ethnic background, were not collected. Family details structure such as number of siblings, age, and gender siblings were recorded (Matsumoto, 1987).

Design

The dependent variable in this investigation was participants’ responses to the various tasks they were required to perform and their emotional responses to the cartoons shown to them (Tice, & Bratslavsky, 2000).

This study involved one within subject independent variable; the pen holding condition. The dependent variables, on the other hand, were two and included the difficulty ratings and amusement ratings (Carlsmith, Ellsworth, & Aronson, 1976).

Materials

Twelve cartoons from a magazine were used to induce stimuli in the participants.

Other materials required for the experiment included a felt tipped pen for joining the different points on the paper, an alcohol swab for disinfecting their hands and the pen, and a paper tissue for wiping their hands and pen (Buck, 1980).

Procedure

Students from the 2011 Developmental Psychology class worked in pairs to conduct the interview, which consisted of the unexpected contents task. Participants were put into three groups consisting of 35, 33, and 33 members.

The experimenter explained to them the various ways one can use to hold a pen. The tasks in this experiment were in four parts, which had been printed on different sheets of paper but given to the participant as a booklet of bound pages.

Participants were asked to hold the pen using their non-preferred hand, teeth or lips (depending on which group they were in), to draw a line between the two asterisks on the page provided to them (Laird, Wagener, Halal, & Szegda, 1982).

The second task instructed them to draw a line connecting 10 ordered digits on in an ascending order starting at 1.

The third task involved underlining the vowels among the letters on the page availed to them. It was required of them to rate on the response sheet how difficult it was in performing the various tasks assigned to them as described before (Leventhal & Cupchik, 1976).

In the fourth task, they were shown different cartoons from magazines. It was required of them to rate each of these cartoons on a system of measurement, which ranged from zero (not at all funny) to nine (very funny).

They were to rate these cartoons while maintaining their initial positions with the pen in their teeth, or lips or the non-preferred hand (McCaul, Holmes, & Solomon, 1982).

Result

Data were analysed using Chi-Square (X2). The experimental study conducted among 101 participants: 76 Females (75.2%) and 25 males (24.8%).

The dependent variables given more emphasis were the funniness ratings for the various cartoons shown to the participants in different groups (Bower, 1981).

As before explained, the effect of facial feedback was anticipated to be confusing as opposed to the funniness ratings.

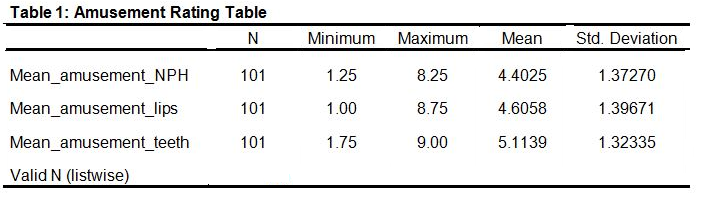

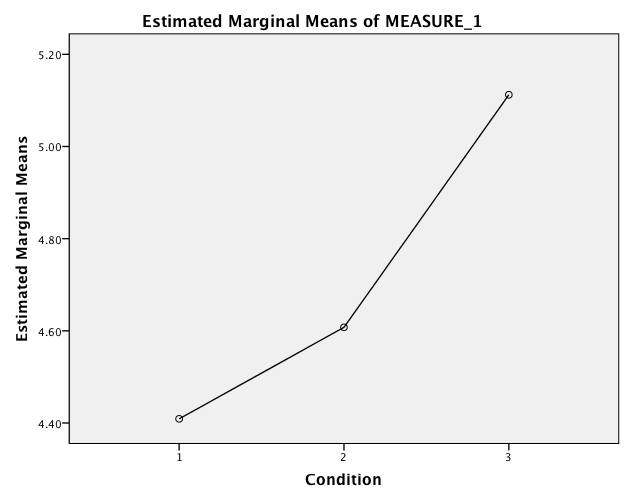

Participants who held pens in their teeth when cartoons were shown to them had highest (M=5.1139) amusement rating as compared to those holding the pen in their non-preferred hand (M=4.4025).

Basing on the facial feedback hypothesis, the prediction was that cartoons would have the highest funniness rating only when those muscles related to smiling constrained. As seen, those who held their pens in the lips were rated in between those in the lips and those in the teeth (M=4.6058).

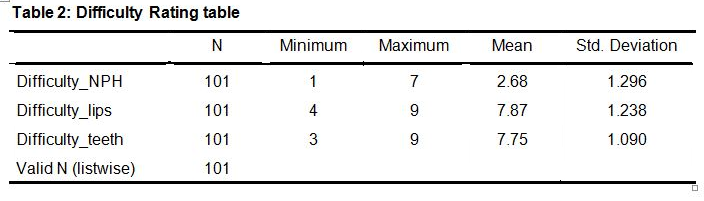

In terms of difficulty ratings, it can be summarized that the harder it was for the participants in gripping the pens, the more they were inhibited from experiencing the humor within what was being shown to them, and therefore, the less amusing they appeared to the participants (Bern, 1967).

This is evident from the difficulty table above that it was less difficult for participants to perform tasks when holding their pens in non-preferred hand (M=2.68) than when the pen was held in the lips (M=7.87) or teeth (M=7.75).

All the cartoons received the highest funniness rating when pens were held in the teeth whereas the lowest funniness rating for all the cartoons was recorded when pens were held in the non-preferred hand (Gavanski, 1986).

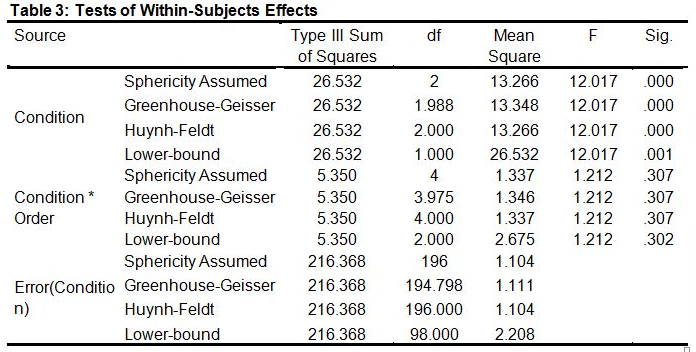

There was no considerable relationship between the investigational environments with the cartoons originating from mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) hence regarding them as in the subject factor F<1 (refer to Table 3).

When combined, these results imply that the suppressing the activities of the muscles related to subdued participant’s feeling of humor. However, any facilitation of the activity increased the intensity of their feeling (Leventhal, & Scherer, 1987).

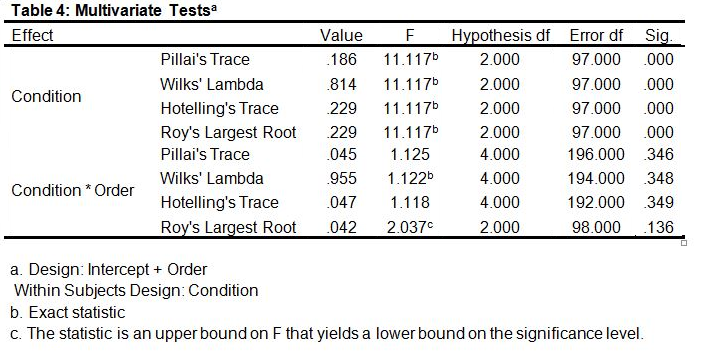

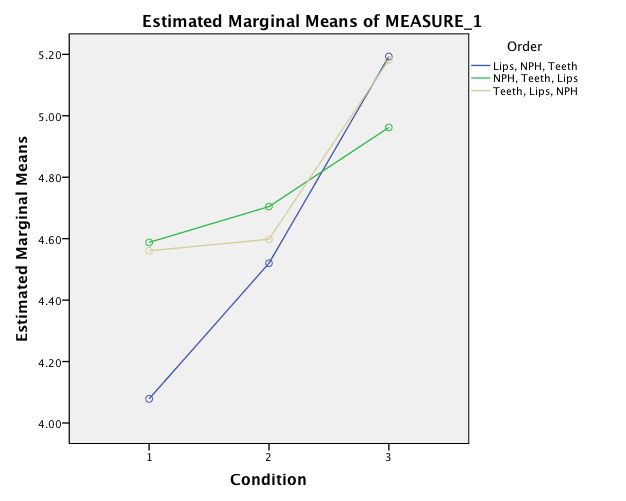

By analyzing the covariance, there was no considerable effect caused by difficulty when treated as a covariate F<1 (Refer to Table 4 and Fig 1 & 2).

Therefore, the disparity in funniness was not as a result of the disparities in the complexity of the three environments used in the experiment (Bern, 1967).

Figure 1: Estimated Marginal Means of MEASURE

Figure 2: Estimated Marginal Means of MEASURE

Discussion

The main objective for this study was to manipulate facial expressions by using a different approach, which effectively does not involve interpreting facial expressions. For instance, the rating of the various cartoons was dependent on the stimulation of the muscle related to smiling.

As opposed to the previous studies, this study did not depend on the generation of emotions regarding a particular emotional response. The results from this paradigm have also been consistent with the facial feedback hypothesis.

This is because subjects are asked specifically to contract the facial muscles used to express emotions or asked to perform non-emotional tasks that require contraction of these muscles (Fritz, Sabine, & Leonard, 1988).

The findings reported that emotional feelings were strongest when a proper was enhanced as opposed to when it was suppressed. Holding the pen in different positions had a direct effect on the participants’ emotional response towards the cartoons but did not affect their rating of the cartoons.

Where participants are not helped in distinguishing between cognitive and affective aspects, their ratings will be an amalgam of both (Kraut, 1982).

Funniness rating was higher when the pen was held in the teeth as cartoons were shown and as the participants rated the cartoons. This is because; smiling was enhanced under this condition.

However, funniness rating was lowest when the pen was held in the lips because smiling was suppressed.

Where participants only held their pens in their experimental positions when rating the funniness rating for pens held in the teeth was lower than when pens were held in the lips (Ekman & Oster, 1982).

This implies that the funniness effect lasted a shorter time when participants’ experience was not accompanied by an inhibiting or enhancing factor than when both were present.

The facial feedback hypothesis envisages that the facial feedback has a direct impact on the emotional decision of an individual.

As such, it gives an explanation why those participants who were not aware of the distinction between the two factors of humor responses had their assessment of the cartoons influenced by the facial feedback.

Therefore, findings from this study clearly propose that the effective response to a stimulus intensifies with the facilitation and softening of an expression.

In addition, the implication of cognitive processes is that recognition of the emotional significance of an individual’s facial expressions should not affect the resultant emotional experience (Laird, 1974).

In this study, participants were made to focus more on the task expected of them to perform rather than their emotional responses towards stimuli.

As such, it helped minimize chances of them intentionally adjusting their emotional expressions according to the specific categories outlined to them. It is imperative to note that individuals utilize their facial expressions when inferring their intentions (Lanzetta, Cartwright-Smith, & Kleck, 1976).

Limitations of the Study

The most important aspect is the interplay between the various stimuli and an inner motor program. As a result, the study has not addressed exact mechanism needed for giving facial feedback.

There is a need to elaborately illustrate a proper methodology to be adopted in showing how the mechanism of facial feedback functions. Therefore, future studies should focus more on the different methodology, which removes all forms of confusion (Carlsmith, Ellsworth, & Aronson, 1976).

References

Bern, D. J. (1967). Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review, 74, 183-200.

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36, 129-148.

Buck, R. (1980). Nonverbal behaviour and the theory of emotion: The facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 24.

Carlsmith, J. M., Ellsworth, P. C., & Aronson, E. (1976). Methods of research in social psychology. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Clark, M. S., & Isen, A. M. (1982). Toward understanding the relationship between feeling states and social behaviour. In A. H. Hastorf & A. M. Isen (Eds.), Cognitive social psychology (pp. 73-108). New York: American Elsevier.

Colby, C., & Lanzetta, J. T. (1976). Effects of being observed on expressive subjective and physical responses to painful stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 1211-1218.

Darwin, C. R. (1872). The expression of emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray

Ekman, P., Levenson, R. W., & Friesen, W. V. (1983). Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science, 221, 1208-1210.

Ekman, P., & Oster, H. (1982). Review of research, 1970-1980. In P. Ekman (Ed.), Emotion in the human face, Second edition (pp. 147- 173), New York: Cambridge University Press

Fritz, S., Sabine, S., & Leonard, L.M. (1988). Inhibiting and Facilitating Conditions of the Human Smile: A Nonobtrusive Test of the Facial Feedback Hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 768-777.

Gavanski, I. (1986). Differential sensitivity of humour ratings and mirth responses to cognitive and affective components of the humour response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 209-214.

Hager, J. C. (1982). Asymmetries in facial expressions. In P. Ekman (Ed.), Emotion in the human face, Second edition (pp. 318-352). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Higgins, E. T, Rholes, W. S., & Jones, C. R. (1977). Category accessibility and impression formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 131-154.

Izard, C. E. (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum Press.

Izard, C. E. (1981). Differential emotions theory and the facial activation: Comments on Iburangeau and Ellsworth’s The role of facial response in the experience of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 350-354.

James, W. (1990). The principles of psychology. New York: Holt.

Kraut, R. E. (1982). Social pressure, facial feedback, and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 853-863.

Laird, J. D. (1974). Self-attribution of emotion: The effects of expressive behaviour on the quality of emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 475-486.

Laird, J. D., Wagener, J. J., Halal, M., & Szegda, M. (1982). Remembering what you feel: The effects of emotion on memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 646-657.

Lanzetta, J. T., Cartwright-Smith, J., & Kleck, R. E. (1976). Effects nonverbal dissimulation on emotional experience and autonomic arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 354-370

Leventhal, H., & Cupchik, G. (1976). A process model of humour judgment. Journal of Communication, 26, 190-204.

Leventhal, H., & Mace, W. (1970). The effect of laughter on evaluation of a slapstick movie. Journal of Personality, 38, 16-30

Leventhal, H., & Scherer, K. (1987). The relationship of emotion to cognition: A functional approach to a semantic controversy. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 3-28.

Matsumoto, D. (1987). The role of facial response in the experience of emotion: More methodological problems and a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 769-774.

McCaul, K. D., Holmes, D. S., & Solomon, S. (1982). Voluntary expressive changes and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 145-152.

Tice, D.M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to Feel Good: The Place of Emotion Regulation in the Context of General Self-Control. Psychological Inquiry, 11(3), 149-159.