One of the most distinctive features of the Fred Niblo 1920 film’s The Mark of Zorro, is the fact that it emanates a strongly defined psychological appeal to audiences. In its turn, this explains why, despite its affiliation with the category of black and white silent movies, The Mark of Zorro even today continues to be referred to as such that represents an undeniably high cinematographic value. While being aware of what accounts for the essence of people’s justice-related subliminal anxieties, Niblo was able to ensure that the editing techniques, deployed throughout the film’s entirety, served the purpose of helping viewers to relate to the story of Zorro emotionally. In my paper, I will explore the validity of this thesis at length, while elaborating on other qualitative aspects of Niblo’s film, such as the specifics of the director’s approach to storytelling, acting, directing, etc.

Editing

Fred Niblo’s The Mark of Zorro can be well discussed, as one of the most outstanding examples of the classical editing technique’s successful deployment, because the manner in which the director went about connecting film’s scenes together corresponds to the foremost convention of this particular editing-style. As Gianetti pointed out while referring to the classical paradigm of film-editing, “To keep the action logical and continuous, there must be no confusing breaks in an edited sequence” (Gianetti, 2001, p. 136). In its turn, this explains why, despite the fact that there are many prolonged time-lapses to the story of Zorro acting on behalf of oppressed people, there is an undeniable spirit of a real-time genuineness to the story’s cinematic representation. This can be seen as a clear indication of the fact that Niblo did succeed in ensuring the spatial integrity of the featured characters’ emotions, as there is a strongly defined spirit of a spatial continuity to the action seen on the screen.

The validity of this statement can be well illustrated in regards to the fact that, in the mark of Zorro, subsequent shots organically derive out of each other, which creates the illusion of the action’s ‘seamlessness’. According to Berliner and Cohen (2011), “In a classically edited movie, a character moving from left to right in one shot will, for purposes of continuity, likely be shown moving left to right in an immediately subsequent shot” (p. 45). The mark of Zorro features plenty of perceptually interconnected shots, which leave only a few doubts, as to the discussed film’s affiliation with the conventions of classical editing.

For example, in one shot, we get to see the angered Sergeant Gonzalez moving in the left-wise direction:

The subsequent shot features the same character emerging from out of the frame’s right side:

This, of course, was done for the purpose of increasing the extent of the action’s plausibility.

Another common feature of the classical editing methodology is the fact that it has often been utilized within the context of directors aiming to emphasize the emotional intensity of the plot’s unraveling, “Classical cutting involves editing for dramatic intensity and emotional emphasis rather than for purely physical reasons” (Gianetti, p. 138). This is the reason why the classical approach to editing is often being concerned with the directors’ conscious intention to emphasize the characters’ emotions. The mask of Zorro exposes viewers to a number of shots, which provide them with insights into the workings of the featured characters’ psyche, such as the following ones:

There is another aspect to it – the very genre of The Mark of Zorro, as a silent film, naturally presupposed the inclusion of the characters’ facial closeups as the mean of revealing the motivations behind their behavior. After all, in silent films, directors are being deprived of an opportunity to represent characters, as such, that indulge inaudible conversations with each other. Therefore, hypertrophying the sheer intensity of the characters’ emotions is only the way for directors to go about ensuring the perceptual soundness of the on-screen action. Apparently, while working on The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks never ceased being aware of this fact.

Storytelling

The earlier mentioned fact that the mark of Zorro is being concerned with the deployment of the classical editing-methodology defines the qualitative aspects of this film’s storytelling – the manner in which the movie’s plot unravels, adheres to the principle of cognitive dialectics. That is, in Niblo’s film, it causes delineate effects. This explains the unidirectional flow of events in The mask of Zorro and also the fact that in this film, there are no scenes of characters reflecting upon their memories of the past, as it is commonly the case in the expressionist/formalist works of cinematography. It appears that this contributed to the film’s popularity the most because the dialectical methodology of storytelling is consistent with how people tend to perceive the surrounding reality. The deployed method of storytelling also contributes to the film’s spirit of realism – while exposed to the plot developments, viewers grow to perceive Zorro’s motivations to act in the way he did, as being thoroughly legitimate.

Acting

Another major factor that contributed to the Niblo film’s popularity with the viewing audiences is that there is psychological soundness to the characters’ actions. In its turn, this explains why, even before being revealed that the character of Don Diego is, in fact, Zorro, viewers used to unconsciously recognize him as being so much more than simply the spoiled and self-indulgent son of Alejandro Vega (a wealthy rancher). As Cohen (2010) noted, “Every (film’s) aspect is a joy to behold… (including) the delightful oscillation of the Fairbanks character between the prissy but somehow still appealing Don Diego and the magnificently athletic and smiling Zorro” (p. 158).

Partially, this is the consequence of Fairbanks being able to act in the manner consistent with what happened to be the unconventional manifestations of his character’s existential mode – hence, the well-defined behavioral three-dimensionality of the character of Zorro. Even though that in the film, the rest of the major characters cannot be referred to as such radiate a psychological depth, within the context of how they address life-challenges, there is still much of a lifelike realness about their act. The validity of this suggestion can be shown in relation to the character of Lolita Pulido (Marguerite De La Motte) – the way she acted towards Don Diego, on the one hand, and towards Zorro, on the other, is thoroughly consistent with the essence of women’s deep-seated anxieties towards the representatives of the opposite gender.

Cinematography

There are two most distinctive features of the Niblo film’s cinematography – the fact that the movie in question contains a number of although primitive but realistic special effects/stunts, and also the director’s point in enriching The mark of Zorro with many panoramic shots. The first feature serves the purpose of providing viewers with good entertainment. There is, however, even more to it – while exposed to the scenes in which Zorro jumps up and down, as being nothing short of an acrobat, people in the theater are being prompted to think that one’s ability to act on behalf of justice, cannot be discussed outside of the measure of the concerned individual’s physical fitness. The second mentioned feature serves the purpose of endowing the film with epic undertones. After all, even though there are many comical elements in the movie, the very idea of justice vs. injustice, explored throughout the film’s entirety, implies the representational upscaling of the concerned visuals. Apparently, Niblo considered it having been the matter of crucial importance to encourage viewers to perceive the on-screen action, as such, that reflects the epic subtleties of an ongoing confrontation between good and evil.

Genre

The mark of Zorro belongs to the genre of black and white silent films. This presupposes a number of the film’s cinematographic limitations. For example, with the possible exemption of the character of Zorro, the rest of this movie’s characters are represented as being rather incapable of changing their social-political attitudes. After all, it is specifically the particulars of these characters’ class-affiliation, which define their posture in life. In essence, the wealthier a particular character happened to be, the more wicked of an individual he or she is being shown on the screen.

This is because of the very conceptual format of a silent film deprives directors of an opportunity to represent characters in the state of a continual psychological transformation. At the same time, however, the same format makes it possible for directors to accentuate what happened to be the innermost quality of the characters’ mental predispositions. The reason for this is apparent – in silent films, directors are able to establish a dialectical connection between the specifics of the characters’ physical appearance, on the one hand, and the workings of their psyche, on the other. In its turn, this makes it easier for viewers to relate to the on-screen action, as such, that corresponds to their unconscious suspicions in regards to the effects of people’s appearance on the way they act.

Sound

Being a silent film, The Mark of Zorro does not feature audible conversations between characters. This, however, is being compensated by the sheer intensity of the characters’ mimics – the observation of the characters’ facial expressions, at the time when they supposedly come up with audible statements, provides viewers with a good clue, as to what is actually being said. In this respect, the film’s musical accompaniment added later by the distributor (United Artists), comes in particularly handy. This is because it does allow viewers to gain a better insight into the discursive significance of the action featured in every scene.

For example, in the scene where Sergeant Gonzalez brags about his intention to find and kill Zorro (00.06.42) we get to hear a particularly unpleasant/dissonant music, which emphasizes this character’s perceptual arrogance. The scene in which Zorro fights with Gonzales for the first time is accompanied by the unmistakably heroic and yet cheerful music, which intensifies the viewers’ satisfaction of seeing Gonzales being humiliated. The musical accompaniment also plays an important part in the film’s romantic scenes, as it stresses the genuineness of Zorro’s feelings towards Lolita.

Style and directing

When it comes to discussing the Niblo’s style of directing, it becomes quite apparent that, while filming The mark of Zorro, he used to encourage actors to adopt the existential identity of their characters, in order for them to be able to improvise successfully. The validity of this suggestion can be well seen in relation to the performance of Noah Beery (Sergeant Gonzales), for example. After all, there are many prolonged takes in the film, where Sergeant Gonzales acts in the manner clearly reflective of what happened to be his state of mind at the time when these takes were filmed.

What it means is that, after having been provided with the general performance-related instructions, Noah Beery was given the liberty to explore his character in the way he considered it the most appropriate one. Essentially the same applies to the character of Douglas Fairbanks, which is the reason why the on-screen personality of Zorro appears being strongly affected by the personality of the actor that played his role. Fred Niblo’s interpretation of the story of Zorro also bears the clear mark of the director’s sense of humor, which explains why The mark of Zorro contains a number of gags, which were meant to mock the very socially upheld notion of ‘respectfulness’, such as the one concerned with Zorro leaving the mark ‘Z’ on Gonzalez’s rear end with its sword:

Thus, it will be fully appropriate, on my part, to suggest that it was namely Niblo’s willingness to defy what used to be the provisions of cinematographic conventionality at the time, which may be well defined as the most distinctive aspect of his style of directing.

Textual themes

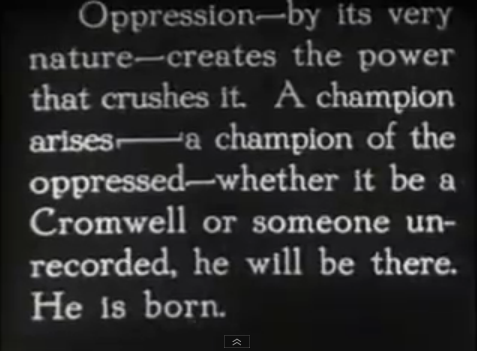

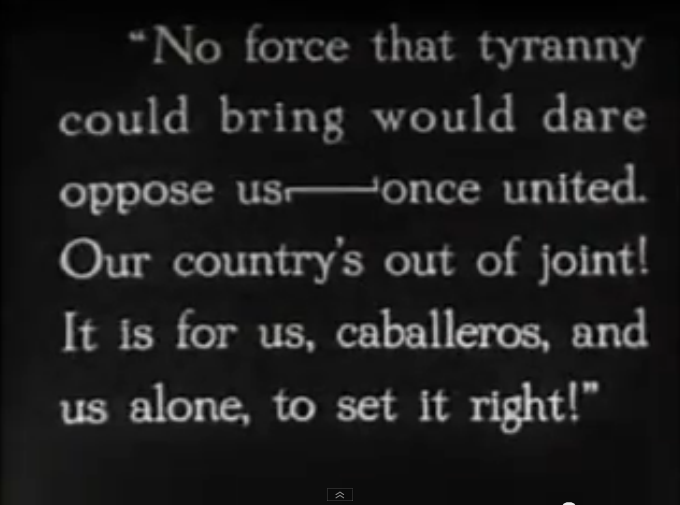

Given the film’s affiliation with the genre of silent movies, it is fully explainable why the on-screen action is being periodically interrupted by the takes of textual intertitles. However, unlike what it was the case with silent films produced earlier, in The Mark of Zorro, these intertitles do not only serve the purpose of ensuring a more or less smooth transition from one scene to another and providing glimpses into the semantic content of dialogues between characters. They are also meant to encourage viewers to contemplate on the explored theme of justice vs. injustice:

Apparently, Niblo did not only want his film to entertain people, but also to encourage them to grow aware of what the notion of oppression stands for, and about how oppressors can be effectively opposed. This, of course, allows us to refer to the mark of Zorro as being revolutionary to an extent.

Analysis and interpretation

The mark of Zorro is best analyzed and interpreted within the conceptual framework of classical/realist cinematography. While deploying the earlier mentioned cinematographic techniques (such as the cut to continuity), the director aimed at both: ensuring the realist subtleties of the depicted action and increasing the extent of this action’s dramatism. This is the reason why, despite the fact that the mark of Zorro features a number of rather unrealistic physical stunts, performed by the characters, it nevertheless can be well-referred to as an intellectually honest cinematographic piece.

Apparently, Niblo deliberately strived to refrain from exposing viewers to his own highly subjective interpretations of the explored themes and motifs, as it is usually the case with formalist/expressionist directors while allowing the members of viewing audiences to enjoy the liberty of assessing the moral implications of Zorro’s struggle against oppression from an essentially rationalistic perspective. Partially, this explains the film’s unwavering appeal – the cinematographic action, concerned with exploring the theme of a perpetual struggle of good against evil, represents the objective value of a ‘thing in itself’.

Impact of society on the film and vice versa

In order to be able to understand the full scope of the Niblo film’s discursive implications, one will need to take into account the specifics of a socio-political situation in America at the time of its production. After all, it does not represent much of a secret that, at the time of this movie’s filming, American society was deeply divided along class lines. Therefore, there is nothing particularly odd about the fact that the mark of Zorro subtly conveys the message that the actual source of the societal evil is people’s class-inequality.

The potential impact of this message upon the Capitalist society is clear. Those who have watched The Mark of Zorro, during the course of the 20th century’s twenties, would naturally grow to question the appropriateness of the situation when the representatives of social elites enjoy an undisputed dominance within the society, at the expense of denying impoverished citizens the opportunity of social advancement. Thus, it will not be much of an exaggeration, on my part, to suggest that Niblo’s film did, in fact, contribute to the process of the American society becoming progressively fairer.

I believe that the earlier provided line of argumentation fully correlates with the paper’s initial thesis.

References

Berliner, T. & Cohen, D. (2011). The illusion of continuity: Active perception and the classical editing system. Journal of Film & Video, 63 (1), 44-63.

Cohen, P. (2010). Douglas Fairbanks: A modern musketeer. The Moving Image, 10 (2), 156-159.

Gianetti, L. (2001). Understanding movies (9th edition). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Niblo, F. (Director). (1920). The mark of Zorro [Motion picture]. United States: United Artists.