Introduction

K-pop music has enjoyed phenomenal international success over the past decade and has become an ambassador of modern Korean culture. It has become not only a source of multimillion-dollar income but also sets trends in related fields, including fashion, cosmetics, advertising, and plastic surgery. Although Korean idols of modern K-pop music have many fans, they also receive criticism.

However, they are more susceptible to gender inequality and stereotypes, which are part of the industry. The biggest problem the k-pop industry has with the general is the slow progress of social gender roles. While male idols enjoy the freedom to choose their image and refute stereotypes of masculinity through a more androgynous style, women are limited in terms of self-expression. In the industry, they are forced to illustrate femininity and fragility in order to meet the prevailing notions of gender roles in society. This circumstance gives rise to gender biases that are broadcast to the audience and root outdated images.

Gender Bias in Korean Society

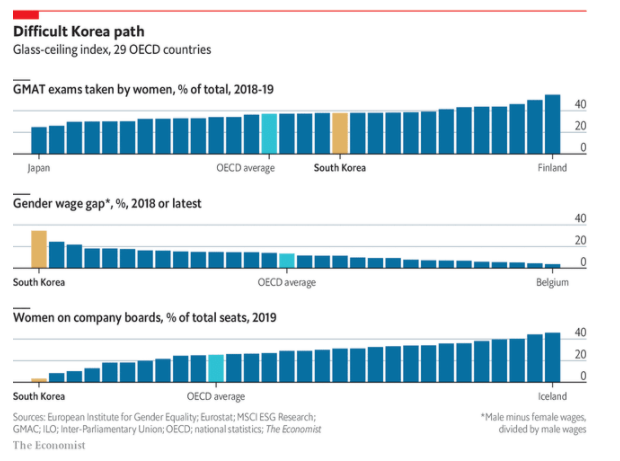

Gender discrimination is an integral part of patriarchal culture, which is also true in South Korea. However, modern society pays more and more attention to the problem of inequality, which allows women to declare the existing situation. The so-called glass ceiling is a common problem in Korea, as the country was ranked 30 of the 36 among the OECD nations for female employment in 2018 (“Attempting To Break Through,” 2019). The country was ranked 115 out of 149 in the World Economic Forum’s global study on gender wage inequality (“Attempting To Break Through,” 2019). However, Jung & Cho (2019) report that Korean women are significantly affected by the glass ceiling in relation to job security. Moreover, in South Korea, according to researchers, there is a dual labor market in which women are at a disadvantage (Jung and Cho, 2019). It is also noteworthy that South Korea has the highest level of education among women aged 25 to 34 among the OECD nations (“Attempting To Break Through,” 2019). These data show that there is a long tradition of gender bias that currently affects the economic life of women in South Korea.

Despite recent efforts to eliminate discrimination in both economic and political spheres, Korean society remains deeply patriarchal. Men and women are expected to fulfill certain gender roles, which are actively promoted by the state. The main problem in South Korea’s labor law in this regard is the low penalties for gender discrimination in employment. In particular, women in South Korea “regularly face questions about their marriage status and plans for having children when applying for a job” (Stangarone, 2019). Such questions when applying for a job are illegal under Korean labor law. However, when KB Kookmin Bank discriminated against 112 women candidates, the company paid only $ 4,500 in fines (Stangarone, 2019). This example illustrates how gender bias is rooted in Korean society and affects all areas of the country’s life. In particular, the Korean government does not seek to legislatively regulate this situation.

Korean Pop Culture Tradition

Gender inequality within Korean society has been widely reported recently. However, it is most noticeable in the media and music industry, where objectification and sexualization of female images dominate. In the news, one can often see reports of tragic events which happen to Korean celebrities. For example, in January 2021, Korean society was rocked by the suicide of young actress and model Song Yoo-Jung (Smith, 2021). This event was only part of a chain of similar incidents that took place in the Korean media space. Increasingly, young actresses, models, and singers face emotional distress and commit suicide. There are many reasons for such tragic events, but the most important of them are high career expectations and public pressure.

The K-pop industry is often criticized for the emotional pressures which are put on idols, particularly female. K-Pop idols’ life is extremely public, and they are almost constantly busy with work. These circumstances negatively affect the mental state of Korean celebrities. Regarding the suicide of the young singer and actress Sulli, it is reported that “tabloids and gossip television drive a culture of constant scrutiny” (Ryall, 2019). However, it can be argued that such events affect not only women idols but also men since episodes of such suicides among male celebrities are also known. For example, the tragic events which led to the suicide of Kim Jong-hyun in 2017 or the death of Cha In-ha in 2019 are discussed in public (Smith, 2021; Ryall, 2019). In fact, the pressures in the media space affect young people regardless of gender. However, female idols are subject to higher levels of social expectation and more pressure from society.

Although the K-pop industry is the most progressive industry in Korean entertainment, it is also associated with a media tradition. The Korean Institute for Gender Equality Promotion and Education found in a recent study that Korea’s most-watched TV programs show 56 cases of gender bias in just seven days (Kim, 2018). Some of the episodes featured even promoted sexual harassment or gender-based violence. However, to a large extent, Korean television entertainment programs exploit lookism and sexual objectification of women. This circumstance is important in the context of the study of gender inequality in the K-pop industry since its roots are in traditional entertainment media programs. Thus, when combined with the discussion of patriarchal Korean gender values, such content is controversial.

Korean dramas, K-pop music, and beauty products have had great global success. However, “rapid industrialization outpaces the slow changes of its society, which is not to say that Korean society is completely backward — but it is still considered quite conservative compared to other developed societies” (Cariappa, 2020, p. 3). The so-called Korean Wave has taken over the European world, not least due to its special cultural traditions (Chang & Lee, 2017). The direction of these products, which are internationally popular, sets the vector for the development of society. However, changing global market conditions are not conducive to the transformations in gender roles that are represented in Korean society. The K-pop industry illustrates how gender biases are rooted in the values of Korean culture and how they influence the perception of women and men in both Korea and the West.

K-pop Industry Gender Biases

The K-pop industry, in particular, is built around gender stereotypes featured on television, including lookism and sexualization. The images of K-pop idols, especially women, are often manipulated to attract audiences. The emphasis in lyrics, music videos, and performances is on sexual content and the objectification of images of young women (Lin & Rudolf, 2017). This picture is consistent with both the Western view of Asian exotic women as sexual objects and the intra-Korean expectations of fragile and weak girls. Despite the fact that the K-pop industry is mainly focused on female audiences and exploits images of male idols, this situation only exacerbates the position of women in this area and reinforces gender stereotypes. Moreover, the images of young K-pop idols of women also influence the perception of their young audience by shaping gender biases among them.

Despite the fact that many K-pop stars have been striving to challenge gender stereotypes lately, a lot of groups still align with the stereotypes. Laurie (2016) notes that k-pop is based on “idealized images of youth, gender, race, and sexuality that stitch together the genre as a whole” (p. 226). In particular, the producers of various groups and idols deliberately create images of overt sexual objectification to attract audiences. In particular, this aspect may be the reason for the popularity of the genre both in the West and in Korea.

However, the widespread gender bias in the industry hinders the development of gender equality both in the media space and in society. Song (2016) explores the images of provocative clothing featured in K-pop idol music videos from 2004-2005 and 2014-2015. According to the data, the average found a ratio of images of sexuality among male and female groups is 0.63 to 3.45 in 2004-2005 (Song, 2016, p. 28). In 2014-2015, these indicators increased to the ratio of 0.8 and 10.68, respectively (Song, 2016, p. 28). Thus, in the past decade, the number of cases of sexual objectification of Korean female idols has almost tripled, while this aspect for male idols has hardly changed. Despite the fact that the number of female K-pop idols remains significantly lower than that of men, they use more sexual content in their videos.

The main bias of modern K-Pop culture is the beauty standards which girls must meet. Dr. S. Heijin Lee notes that the more traditional type of idol suggests fragility, cuteness, and long legs (The Korea Society, 2018). Lin & Rudolf (2017) also emphasize that “K-pop fans are more likely to support the traditional view that the man should be the family’s main breadwinner” (p. 49). Thus, their idols and their images form certain expectations of the audience related to gender roles. Modern K-pop idols opt for more rebellious imagery; they are also subject to a common stereotype. Despite the fact that the industry has been represented by more diverse concepts in recent years, women also meet a number of restrictions and expectations in it. Lee also notes that men in the same context enjoy greater freedom since by exploiting the image of masculinity, they also exhibit androgynous traits depending on the conditions (The Korea Society, 2018). Thus, men, unlike women, can use a wider range of behaviors that will be acceptable to them. In contrast, female idols must follow the rigid canons and frameworks of the genre.

A separate gender-specific feature of the K-pop industry is the prevalence of plastic surgery. While male idols are also subject to objectification and should be the personification of a perfect physical body, women are more likely to resort to the services of plastic surgeons. Lee points out that in today’s Korean society, surgical modification is a way for women to gain confidence (The Korea Society, 2018). In particular, the K-pop industry is the main advertising for this trend through the representation of the ideal bodies of female idols. Korean k-pop group “Six Bombs” even used their before and after photos of plastic surgery to promote their new song in 2017 (Asian Boss, 2017). Moreover, many Koreans underline that appearance is a priority characteristic for a K-pop idol, and surgeries can help them achieve success (Asian Boss, 2017). This circumstance also ensures the sustainability of gender bias, as the industry sets uniform beauty standards that both fans and band members aspire to. The need for perfect physical shape also results in increased emotional pressure on idols.

Additionally, the prevalence of plastic surgery among male K-pop group members is not widely advertised or discussed. McGrory (2019) notes that “‘soft masculinity’ or flower boys has surfaced with many Korean men getting surgery to look like pretty male K-pop idols.” Modern K-pop idols challenge the concepts of true masculinity by wearing makeup, manicures, and trendy hairstyles. Men in the industry can afford to polarize their imagery without facing public criticism. Women, on the other hand, cannot widely use the androgynous style for successful promotion. The industry presents stricter standards for women to follow in order to look feminine and innocent (Shlufman & Shin, 2020). Whereas among male idols, groups as BTS exploit the images of soft boys, female idols who go against the stereotypes are few. One of them is Amber Josephine Liu, who wears short hair and baggy clothes, making her look androgynous and atypical in the industry. The girl notes that in 2009 when she joined the K-pop group, there was no other such singer in the industry (Shlufman & Shin, 2020). However, Amber Josephine Liu soon became a role model for many Korean girls and idols.

Despite the changes taking place in the industry, progress has been extremely slow. While most of the audience for Korean products, including the K-pop industry, are women, it is beneficial for producers to exploit traditional imagery (Chang & Lee, 2017). Images of more feminine men and traditionally sweet women are the most common because of the audience the product is targeting. Given the limited prevalence of the feminist movement in South Korea, radical changes should not be expected in the coming years (Cariappa, 2020). Thus, while K-pop culture is shaped by traditional Korean gender roles, it also translates them to society and audiences. However, the image of men in the industry is changing rapidly, while female stereotypes are transforming little.

Another significant aspect of the K-pop industry is the relationship between idols. In particular, same-sex relationships or their manifestations have been widespread among members of male groups lately, which delights fans (The Korea Society, 2018). However, among female collectives, LGBTQ character relationships are not common and even condemned. Female idols are expected to interact with men, allowing fans to idealize their relationship. While the K-pop community is considered one of the most LGBTQ-friendly, this statement mostly applies only to men (The Korea Society, 2018). In contrast, female idols remain models of traditional gender roles. In this way, the industry promotes freer ideas about men than women. Male idols enjoy the freedom to express their androgyny and homosexuality, even as part of their marketing efforts. Female idols, on the contrary, are forced to obey the established canons and rules in society that do not allow them to exhibit non-stereotypical behavior.

Gender discrimination in the K-pop industry finds many expressions beyond LGBTQ manifestations. BeBoss TV (2020) gives examples of how double standards affect idols of different genders. For example, overly revealing clothing is a reason for criticizing female idols, while a half-naked male body on stage is welcome. Additionally, physical imperfections in the form of non-standard weights are also undesirable for women and normal for men. The author emphasizes that women’s groups are often compared to men’s from a disadvantageous side (BeBoss TV, 2020). Moreover, supporting the feminist movement among Korean K-pop idols is often subject to criticism, while it is encouraged in Western society and male idols. This fact corresponds to the fact that in Korean society, feminism is often perceived as aggression and hostility towards men and not a manifestation of women’s rights (Cariappa, 2020). Therefore, female K-pop idols must maintain the gentle and naive image which is the role model in the industry. They cannot have an opinion or a voice, whereas individuality in male idols is praised.

Conclusion

The overall discussion of gender bias in the k-pop industry is based on traditional ideas about gender roles in modern Korean society. Female idols, unlike male idols, are examples of traditional values and are forced to follow a rigid framework. Men in the industry can use the androgyny and manifestations of LGBTQ freely and gain fan approval. Women in K-pop can only exploit the image of fragile and feminine creatures, and any deviation from the standards is criticized. Thus, the stereotypes of Korean society are applicable to the K-pop industry, which illustrates them in miniature. This situation may indicate the lack of sufficiently rapid progress towards gender equality in South Korea, as well as insufficient government efforts to promote it.

References

Asian Boss. (2017). What Koreans think of K-pop and plastic surgery [Video]. YouTube.

Attempting to break through gender bias in South Korean society. (2019). Unreserved. Web.

BeBoss TV. (2020). Convincing proofs for GENDER INEQUALITY in Kpop [Video]. YouTube.

Cariappa, N. (2020). Through the lens of Koreans: The influence of media on perceptions of feminism. Master’s Projects and Capstones, 1-39. Web.

Chang, P. L., & Lee, I. H. (2017). Cultural preferences in international trade: Evidence from the globalization of Korean pop culture. Research Collection School of Economics, 1-53. Web.

Jung, H., & Cho, J. (2019). Gender inequality of job security: Veiling glass ceiling in Korea. Journal of Asia Pacific Economy, 25(4), 1-20. Web.

Kim, S. H. (2018). Gender bias rampant in Korean TV entertainment shows: study. The Korean Herald. Web.

Laurie, T. (2016). Toward a gender aesthetics of K-pop. In I. Chapman & H. Johnson (Eds.), Global glam and popular music: Style and spectacle from the 1970s to the 2000s (pp. 214-231). Routledge.

Lin, X., & Rudolf, R. (2017). Does K-pop reinforce gender inequalities? Empirical evidence from a new data set. Asian Women, 33(4), 27-54. Web.

McGrory, K. (2019). How male K-pop stars are challenging gender norms and looking great while doing it. Medium. Web.

Ryall, J. (2019). How South Korea’s K-pop world takes a toll on celebrities. DW. Web.

Shlufman, D., & Shin, G. (2020). How K-Pop is redefining gender roles in South Korea. The Echo. Web.

Smith, F. (2021). South Korea celebrity suicides put spotlight on gender inequality. DW. Web.

Song, B. (2016). Seeing is believing: Content analysis of sexual content in Korean music videos [PDF file]. Web.

South Korean women are fighting to be heard. (2020). The Economist. Web.

Stangarone, T. (2019). Gender inequality makes South Korea poorer. The Diplomat. Web.

The Korea Society. (2018). Gender politics of Kpop [Video]. YouTube.