Introduction

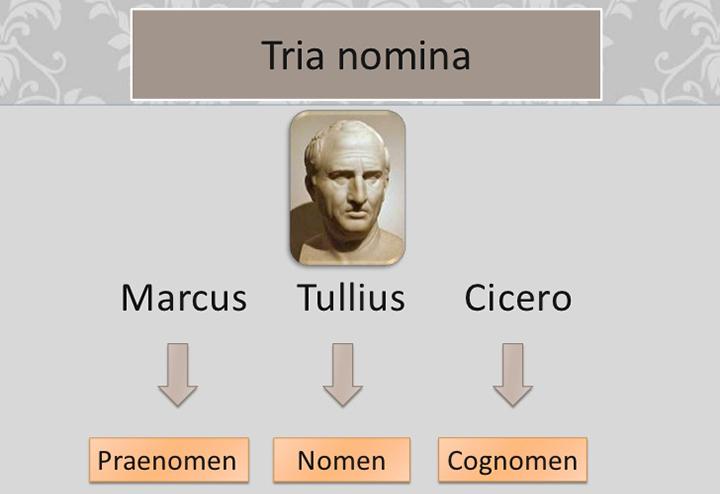

The approach to naming and the development of a naming system represents a reflection of a unique language and its evolution. Since the Greeks were more inclined to adopt everything new, it is not surprising that many of the first Christian congregations were formed on their lands. Christian communities grew and flourished in cities such as Patras, Corinth, Thessaloniki, Philippi, and Athens. The tradition of Christian naming led to a decline of ‘tria nomina’ first in these parts and then across the whole empire (Kantola & Nuorluoto, 2022). Initially, ‘tria nomina’ consisted of praenomen, nomen, and cognomen (Figure 1). However, later Roman names were shortened and used alongside Greek names. Due to a combination of sociocultural factors and economic issues, Greek names gradually ousted the Roman one, while also borrowing certain elements from it and establishing a cultural continuity.

Analysis

At first glance, there was a notable similarity between the two naming systems. At the same time, the Roman approach to naming contained several critical distinctions from others, including the Greek one, which eventually substituted it. For instance, the existence of the praenomen, or the first name, as one of the ore attributes of the roman naming framework, should be mentioned. The remnants of the specified naming system can be found in the present-day context of most languages, with the first name and the last name being the key elements of the naming system as it is applied to people. Therefore, the framework used in ancient Greece and Rome has acquired tremendous legacy millennia after both civilizations ceased to exist.

However, for a number of reasons, the Roman naming system collapsed some time after the collapse of imperial power in the West. The praenomen had already become insufficient in written sources in the fourth century, and by the fifth century, it was preserved only by the most conservative parts of the old Roman aristocracy (Kantola & Nuorluoto, 2022). As Roman institutions and social structures gradually disappeared during the sixth century, the need to distinguish between nomens and cognomens also disappeared. The Greek naming system, vice versa, spread across the country. By the end of the seventh century, the population of Western Europe had completely returned to individual names. But many of the names that originated within the ‘trial nomina’ have been adapted to use and have survived to the present.

To understand the reasons and key driving factors behind the described permutations in the naming framework and the transfer from the Roman approach to the Greek one, one must consider the socioeconomic and sociocultural factors driving the change. Specifically, delving into the history of the Ancient Greece and Roe evolution, one will spot the undeniable and overwhelming effect of the elite as the demographic that shaped the sociocultural context and defined the changes within it (Breytenbach, 2018). Therefore, it would be reasonable to conclude that the introduction of the praenomen and the gentilicium, or the family name, can be seen as the direct influence of the Roman culture. Namely, the fact that in the roman community, the presence of the elite class was significantly more pronounced, should be regarded as the core factor behind the described developments.

Additionally, linking the change in the naming system and the relevant trends, one should also focus on the fact that the use of the gentilicium, or the family name, was initially associated with the ruling class, namely, the emperor and the affiliated people (Kantola, 2022). Therefore, the tradition to incorporate the last name into the naming framework should be attributed to the permutations within the social system and hierarchy of ancient Rome and Greece. Furthermore, the tradition to exclude women’s family names and use men’s ones instead can also be seen as the extension of the Greek naming framework, which would percolate into the Roman approach to the naming process (Breytenbach, 2018). Defined by the specifics of the gender roles within the Roman and Greek communities, as well as the overall inequality between men and women in the specified societies, the described framework for naming was eventually imprinted onto the European naming conventions.

Conclusion

Thus, it can be concluded that the Greek naming system, initially used only for slaves and servants, triumphed over a more prestigious Roman equivalent. On the one hand, the reasons for it were changing the social structure of the society, where social strata gradually became less pronounced, and, on the other, the emergence of Christian ideas within Greece. Moreover, the natural tendency for shortening played a significant part in this process, making the Greek naming system preferable to the Roman one.

References

Breytenbach, C. (2018). Tria nomina [Online image]. Relational identity and Roman name-giving among Lycaonian Christians. In C. Breytenbach & J. M. Ogereau (Eds.), Authority and identity in emerging Christianities in Asia Minor and Greece (pp. 144-167). Brill. Web.

Kantola U., Nuorluoto T. (2022). Names and identities of Greek elites with Roman citizenship. In C. Krötzl, K. Mustakallio & M. Tamminen (Eds.), Negotiation, collaboration and conflict in ancient and medieval communities (pp. 20-26). Routledge.

Tales of times forgotten. (n.d.) Web.