Abstract

The main aim of this study was to assess the consumer motivation and satisfaction for the Green Hotel in China. The results of the study suggested that participants have medium level knowledge of the Green Hotel. In addition, it can be seen that more than half of the participants have expressed their concern regarding the environmental problem concerning the hotel.

In order to gain a more detailed picture of the level of environmental concern, the aggregate mean score was classified into three levels: low (below 2), medium (2-4), and high (4-5). The majority of the participants agree or strongly agree that “This Green Hotel offers a good service that is worth its price”, “The prices are acceptable”, and “Compared to the price of other hotels, this Green Hotel charge fairly”. This suggests that participants have a positive attitude towards the fair price of the Green Hotel. Nearly half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Overall, I am satisfied with the experience in this Green Hotel”, “I am glad to stay in the Green Hotel again in the future”. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the scores ranged between 10 and 11, which also indicate a medium level satisfaction.

Introduction

Overview

This chapter covers the background to the study, problem statement, research objectives, hypotheses and the significance of the study.

Background to the study

Consumer motivation is viewed as a state of the condition of necessities that motivate a man to participate in a certain activity or movement that has a higher likelihood of conceding him/her a certain level of desired fulfilment (Sivadas & Baker-Prewitt 2000, p. 80). Consumer motivation is a technique concerning inclinations made by people or secondary living beings among substitute types of intentional action (Srinivasana, Andersona & Ponnavolub 2002, p. 46; Simon 2007, p. 125). Other researchers recommended that ‘the current and quick impact on the energy, bearing and constancy of activity can be termed as motivation’ (Wal, Van & Bond 2002, p. 327). In the same way, some scholars implied that ‘inspiration can be offered to the consumers, according to the accompanying systems, the standard or conventional methodology, human relations methodology, disguised inspiration and rivalry’ (Yuen & Chan 2010, p. 230; Sirdeshmukh, Singh & Sabol 2002, p. 27).

Similarly, other scholars discovered that ‘business chiefs are endeavouring to set up and keep up an environment that is greater for the fulfilment of holidaymakers, who are endeavouring together in gatherings towards achieving of foreordained objectives’ (Szymanski & Henard 2001, p. 24). Other scholars conducted a study that concentrated on the examples of get-away for consumer visitors from Germany by focusing on their travel modes, travel destination, length of stay, kind of settlement picked, and excursion recollections. They discovered that ‘all the mentioned components were instrumental in affecting the visitors to travel’ (Su 2004, p. 400). A few studies have been completed to scout the examples of conduct of the consumers. In the same way, many scholars directed a study that tried to investigate the tourism exercises of the consumers and their conduct with regards to shopping. The holidaymakers’ travel exercises that were investigated in this study included social tourism, open air tourism and diversion tourism. The studies came to a conclusion that ‘the profiles of the travellers were differing as to their likelihood to shop at merchandising channels, their decision of shopping centres, and their wellsprings of data concerning the accessible shopping exercises’ (Stecher & Rosse 2007, p. 781).

Statement of the problem

It is very beneficial for the consumers to learn about the travel destination before making up their minds to travel. Consumers who are uncertain do rely on information from travel agencies so that they can be equipped with the necessary information concerning the destination site (Abdullah et al. 2012, p. 177; Abu & Roslin 2008, p. 60). The search for information relate to the destined visit site by the consumers is motivated by the various contingencies in the marketplace and the nature of the visits (Berman & Evans 2006). Consumers who travel on a regular basis have more affinity to receive information that relates to the travel product or the travel destination; with this regard they are more enthusiastic about spreading the information to other interested travellers (Bennett & Rundle-Thiele 2002, p. 200).

Objectives of the study

The general objective of this study was to determine the consumer motivation and satisfaction for Green Hotel in China. In line with a general objective, the study examined the following specific objectives:

- To understand the effectiveness of quality of service for consumer motivation and satisfaction,

- To determine the influence of the hotel facilities on consumer motivation and satisfaction,

- To determine the influence of subjective norms on consumer motivation and satisfaction,

- To investigate the influence of the hotel knowledge about consumer motivation and satisfaction,

- To investigate the influence of the cost of services on consumer motivation and satisfaction,

- To make recommendations on the possible future research.

Hypotheses of the study

In order to meet the above objectives, the following hypotheses were tested:

- H1: The quality of service motivates and satisfies the consumers at the Green Hotel,

- H2: The hotel facilities motivate and satisfies the consumers at the Green Hotel,

- H3: The subjective norms motivate and satisfies the consumers at the Green Hotel,

- H4: The hotel knowledge motivates and satisfies the consumers at the Green Hotel,

- H5: The cost of services motivates and satisfies the consumers at the Green Hotel.

Justification of the Study

The findings of this study are of great value to policy makers. They provide the policy makers with a wide exposure with regard to the assessment of the consumer motivation and satisfaction, thus enabling them to adopt the relevant strategies in line with the situation. The findings of this study also add to the body of knowledge of related studies about the assessment of the consumer motivation and satisfaction.

Scope of the Study

The scope of this study was in line with the general objective, which was to determine the consumer motivation and satisfaction for Green Hotel in China. Using primary data and applying statistical techniques, the study explained the variables to meet the research objectives. The study used a cross-sectional research design to meet the objectives. The data of the survey were analysed using statistical techniques.

Literature Review

Introduction

This part surveys the hypotheses, both exact and hypothetical, that are firmly connected to the consumer motivation and satisfaction. An investigation of the past reviews concerning the motivation of the consumers’ figures principally ‘centred around the senior consumers by keeping an eye on their profiles, perceptions and desires’ (Avolio, Walumbwa & Weber 2009, p. 430). A study directed to survey the profiles of the senior shoppers fundamentally focused on two-buyer bunches, more than 50 years and under 50 years. The study discovered that ‘both the two gatherings were roused to go by the yearning to satisfy their pleasure, the longing to rest or unwind, and the craving to meet families or companions; then again, the gathering which was over 50 years old had a higher likelihood of visiting chronicled locales’ (Jamali 2007, p. 380; Yelkur 2011, p. 112; Kouzes & Posner 2003).

General consumer motivation

Heneman (2002, p. 58) found that ‘consumer motivation entails the price of labour’. The incorporation of satisfaction approaches in consumer motivation processes has led to the integration of diverse satisfaction management practices. One of the most notable practices entails the increase in satisfaction levels. Firms are linking motivation to satisfaction in an effort to remain competitive through improved consumer productivity (Li & Green 2010, p. 10). However, in the course of designing the motivation-for-satisfaction schemes, it is imperative for organisations to take into account the relevant factors that affect satisfaction.

Consumer motivation is viewed as a state of the condition of necessities that impact a man to participate in a certain activity or movement that has a higher likelihood of conceding him/her a certain level of wanted fulfilment (Sivadas & Baker-Prewitt 2000, p. 80). The profit and non-profit oriented organisations are increasingly being concerned with the consumer motivation to improve their satisfaction (Hong, Thong & Tam 2005, p. 153; Hoq & Amin 2010, p. 2388). Most organisations are adopting a flat organisational structure to escalate the contact with consumers. Consequently, firms are considering alternative approaches to sustain their consumer level of motivation. This plan has led to the adoption of motivation systems in their consumer motivation plans. One of the systems that are commonly used by organisations entails the integration of motivation and satisfaction.

Hair, Bush and Ortinan (2006, p. 17) pointed out that ‘the similitudes and differentiations that exist between the most youthful consumers and the more established consumers’. The principle inspiration considers that drove the consumers to tour was the need to unwind or to take part in recreation exercises; then again, more seasoned customers were primarily propelled to go by instructive attractions and national attractions. There are different accessible literary works that clarify the different variables that propel visitors to travel. In their study, Ellingson and McFarland (2011, p. 67) uncovered that ‘the business for the customer is not uniform, and they brought up seven portions that identify with the inspiration for the customers’. Some scholars have associated the consumer motivation and conduct with the pecking order of human needs; they were of the opinion that ‘the principle reason that made the travellers be pulled into the predetermined spot of their visit was the longing to accomplish self-completion, the inclination of affection or belongings, furthermore, to achieve the physiological needs’ (Dahesh, Nasab & Ling 2012, p. 142). The portions include scholars, sentiments, physicals, learners, status seekers, neighbourly and dreamers.

Consumer motivation in hotels

The motivation that is associated with the customers’ travel envelops a wide range of the tourists’ practices and their past travel encounters. Consumer motivation is the sort of ‘inspiration that is associated with the motivation behind why individuals choose to travel’ (Codrington 2002, p. 38; Keller 2006, p. 792; Claudia 2012, p. 140). The concept of consumer motivation, therefore, alludes to the classification of a need or a predicament that urges a man to take part in a certain activity that offers him/her a fulfilment (Burns & Bush 2000). Fulfilment does not by any means stem from the joys that the consumers get from the travelling knowledge, yet it is rather the examination that looks at whether the experience fulfilled the consumers as it was relied upon (Harteis 2012, p. 100). Different examinations have uncovered that fulfilment and the brand’s state of mind are identical (Hill & Ettenson 2005, p. 88).

Emotional responses have a noteworthy impact on the encounters of the customers’ utilization process with respect to their decisions on post-buy fulfilments (Hill & Westbrook 2007, p. 47; Holt & Quelch 2009, p. 70; Hughes, Ginnett & Curphy 2012; Jerisat 2004). In this situation, it is accepted that the fulfilment of the consumers is reliant on the execution of the item, the view of the consumer in connection to the item, and the inspirations of the consumers. The proportion between the execution and the observation ascends as the level of the consumer’s fulfilments additionally rises (Jha 2014); the proportion relies upon the way of the encounters that the consumers have in connection to the experience they had imagined or desired.

Disappointment of the customers happens when there is a great uniqueness between what the buyers had expected and what they really encountered. Different researchers have communicated their reactions regarding the understanding of fulfilment as to the desires that the buyers have. Fulfilment is seen to have an association with amazement (Johnson 2008, p. 88). What’s more, many scholars have presumed that ‘consumer satisfaction can happen in different structures; for example, alluring fulfilments, perfect fulfilments, and average fulfilments’ (Kang & Singh 2006, p. 200). At the point when consumers go for occasions, their fulfilment levels are exceedingly joined with their level of inspiration. At the point when the travel destination is alluring, the needs and the inspiration of the visitors are fulfilled (Kantabutra & Avery 2010, p. 42). The view of the destination includes a mixed bag of variables and different fascination destinations that the consumer accepts to have the ability to fulfil his/her wishes or desires.

Consumer motivation in the Green Hotel

The Green Hotel hires employees who have a professional attitude towards their jobs. The positive job attitude is aimed at meeting the needs of the customers and makes them feel more comfortable coming back again. In addition, the management is constantly empowering the staff to make good customer satisfaction skills. This is done through the job training to equip the employees with the relevant skills needed. The Green hotel customers are also motivated though quick responses to their issues. When the customers need any kind of assistance at any given time, the hotel staffs normally respond promptly. The Green hotel guests are normally treated warmly with a lot of respect and professionalism.

The hotel rooms are well maintained and constantly renovated as per the customers’ desires. This is aimed at making the rooms more comfortable and appealing to the customers. The customers are treated as the biggest asset of the hotel and their comfort is highly valued by the management. In addition, to enhance customer motivation, the Green hotel uses advertisement to motivate the customers to visit. Various media channels like the internet and magazines are used by the hotel as a mode of advertisement. Through advertisement, the hotel is in a better position to promote itself and appeal to the targeted customers.

The hotel customers normally prefer a hotel that has policies for protecting the environment. The Green Hotel has various green programs and policies that are aimed at protecting the environment. This is manifested by the well maintained air conditioning systems, keeping data digitally rather than using paper, and also the high energy consuming appliances are replaced by highly proficient appliances, even though they might require a huge amount of money to set up.

Customers who have occupied with efficiency for so long and are more included in the authoritative development and are known as inspired purchasers. Purchaser inspiration can be depicted as the slant of a person to apply high greatness of endeavours (Claudia 2012, p. 140). Purchasers are capable and willing to apply a high greatness of exertion when the shopper’s ability and the employment match is in parity; when due acknowledgment is made for their accomplishments; and when prospects for development are accessible to those customers who want that (Codrington 2002, p. 38). Low confidence among the buyers is an indication of an authoritative sickness that implies an absence of inspiration and requests a high mindful treatment and cure. Consequently, for any business association to finish its destinations and objectives, cheerful purchasers are the need of great importance. To make the purchasers put forth a strong effort; buyer inspiration has turned into an imperative component.

The concept and theories of consumer motivation

Consumer motivation is the study of how, when, why and where people do or do not source for goods or services. It attempts to assess the influence of the clients from external factors such as high salaries and income, the growth of urban lifestyle, among others. It is a common practice for the customers to purchase goods and services for a number of reasons. These reasons may include reinforcing self-concepts, maintaining a given lifestyle, becoming part of a particular group or gaining acceptance in a group they already belong, and or expressing cultural identity. Consumers make their decisions based on the available time. Business chiefs are endeavouring to set up and keep up an environment that is greater for the fulfilment of consumers, who are endeavouring together in groups towards the achievement of foreordained objectives (Kantabutra & Avery 2010, p. 42).

A few studies have been completed to scout the examples of the conduct of the consumers. The profiles of the consumers are differing as to their likelihood to shop at merchandising channels, their decision of shopping centres, and their wellsprings of data concerning the accessible shopping exercises. Consumers compete for access prizes in their environment, such as promotion and motivation increments. Consequently, integrating ethics among buyers at different levels of management plays an essential role in motivating them to put more efforts in their job roles and responsibilities. Subsequently, the administration’s satisfaction is improved considerably. The satisfaction inequality is directly correlated to the union and individual satisfaction.

Purchaser inspiration is a strategy concerning inclinations made by people or subordinate living beings among substitute types of purposeful action (Burns & Bush 2000). Hair, Bush and Ortinan (2006, p. 17) proposed that ‘the present and quick impact on the power, course and ingenuity of activity can be termed as inspiration’. Ellingson and McFarland (2011, p. 67) found that ‘business administrators are endeavouring to build up and keep up an environment that is greater as per the general inclination of individual purchasers who are endeavouring together in gatherings towards accomplishment of the pre-decided objectives’. Interestingly, Heneman (2002, p. 58) expressed that ‘inspiration can be offered to specialists according to the accompanying strategies: the standard or conventional methodology; certain dealing; human relations methodology; disguised inspiration; and rivalry’.

In a related study, Levy and Weitz (2004, p. 152) led a study that ‘concentrated on hotel consumers from Britain, Germany and Japan’. They discovered that the consumers liked to have bundled visits; this was obvious by the critical number of the sightseers in travel parties (Levy & Weitz 2004). At the point when the shoppers travel, they generally pick tenable visit administrators who have a decent notoriety. They additionally verify that ‘their well-being will not be in any danger and that their outing will give them the craved fulfilment’ (Li & Green 2010, p. 10). Other scholars led a survey that principally harped on the characteristics of the consumers; the study provides that ‘the most pivotal segregating variables that existed between the individuals who travel and the individuals who don’t travel were: versatility issues, age, and level of training’ (Kandampully & Suhartanto 2000, p. 347).

The choice of the buyers to lean toward engine-mentor visits are ‘impacted by their demographic attributes, mental qualities and psychographic qualities’ (Abbas & Asghar 2010, p. 33). A study led by other scholars discovered that ‘the customers favoured tourism bundles that offered them fervours and increased the value of their lives’ (Lawler, Porter & Vroom 2009, p. 3). Therefore, Adetule (2011, p. 153) discovered that ‘before the hotel consumers settle on a choice, they generally inquire whether their well-being is shielded and the yearning for security increments as the consumers develop to be more seasoned’. The latest study done by some scholars focused on an audit of the past studies concerning customer inspiration and discovered that ‘the inspiration to travel can be classified into different gatherings, for example, rest and unwinding, training, experience, mingling, and break from everyday examples of life’ (Hong, Thong & Tam 2005, p. 153). Similarly, other researchers reasoned that ‘the noteworthy push and force inspirations of the sightseers were: the longing to look for learning, and the inclination to be safe’ (Hoq & Amin 2010, p. 2388).

Also, some scholars did an audit of the past studies with respect to the consumers’ movement and made a derivation that ‘the more established customers were, for the most part, propelled to go off the longing to unwind, associate, learn, and to pick up fervour’ (Hellstrand 2010, p. 1). In the same way, Heneman (2002, p. 58) in his study uncovered that ‘the inspiration for the consumer was moving towards the yearning to rest or unwind, the longing for physical activity or wellness, and the craving for instruction’. A study led by Jewell (2011, p. 16) affirmed that ‘more youthful consumers are more instructed when contrasted with the older ones, in this manner, they generally complete a data seek before they continue with their visits’. Moreover, the study likewise discovered that the consumers had embraced a society of buying outing bundles that took care of the expenses of both transportation and convenience.

Numerous business associations are progressively applying customer fulfilment through the job of a system of strengthening. Strengthening is the procedure of giving the shoppers power so they can be more applicable to the business association by taking an interest in the choice making procedure. By presenting strengthening, there will be no stream of control from the top echelons of the business downwards. Engaged purchasers will settle on choices all alone since they do have their own voice in what to perform, when to perform and how to perform (Li & Green 2010, p. 10).

Levy and Weitz (2004, p. 152) found that ‘businesses progressively perceive satisfaction as an element that can promote an organisation’s superiority with reference to competition, rather than cost’. This trend is most prevalent within the private sector. Adetule (2011, p. 153) contend that ‘organisations in the private sector are gradually aligning motivation schemes with the consumer or organisational satisfaction’. Consequently, the popularity of satisfaction-related motivation has increased considerably. Jewell (2011, p. 16) defined the satisfaction-related system to include ‘a system which awards workers who have worked above their normal working levels with money’.

Push and pull motivation

Push motivation is likened to self-discipline; where individuals are pushing forward to accomplish a goal. This kind of motivation effortlessly prompts disheartening at whatever point obstructions are realized in the way of its accomplishment. This sort of motivation is questionable. Self-resolve alone is just as solid as the yearning behind the self-control. With push motivation, it is anything but difficult to scrutinize your unique objective when things are complicated, and you ask yourself, “will this be justified despite all the trouble?” (Yelkur 2011, p. 110). Pull motivation is the type of motivation that is significantly more capable than push motivation. The things that an individual needs are so convincing and energising and they appear to force the individual to them. Each consumer has encountered pull motivation at some point. Under pull motivation, the efforts are simple. The consumer needs satisfaction so bad that it just appears to draw the consumer to it. Under pull motivation, the consumer does not need persuading himself to buckle down. The things that an individual needs are so convincing and are attractive (Rust, Zeithaml & Lemon 2004, p. 112).

The push-pull model that was created by Gratton and Jones (2004, p. 410) proposes that ‘tourism is driven by two constraints; the first compel, known as ‘push’, steers the visitor out of his/her home determined by the yearning to go to an unspecified destination’. In this connection, the inspiration of the push power relies upon the fulfilments foreseen by the consumer, the desire to enterprise, renown, learning, and the longing to make new companionships. The second compels, known as ‘pull’, furnishes the consumer with the heading in regards to the decision of the destination (Zineldin 2000 p. 20; Yin 2009). The thought processes of the draw force impact the consumer’s decision on the spot to visit; the powers are joined with the components of the destination and the foundations that characterize tourism. The components of the destination empower the buyer to make verdicts regarding their longings (Saili, Mingli & Zhichao 2012, p. 4300; Roy 2012, p. 62; Roth 2008).

The inner motivational variables stem from the push intentions while the outer motivational components stem from the force thought processes. Recognition is a vibrant process because of the way that the consumers can choose to arrange and to delineate the different stimuli into a helpful and clear way. The impression of the customer, along these lines, changes from the genuine attributes of an item to the way in which the consumer handles and investigates the data (Lussier 2005; Lovvorn & Chen 2011, p. 280). Discernment can happen specifically if the consumer chooses to be particular in his/her presentation, consideration, perceptual blockage and perceptual resistance. It is a typical routine of the shoppers to choose just things they need and shut out the things that they see as superfluous or unfavourable to them. There are two ideas of recognition that come from the consumers’ learning procedure. One of the ideas is the intellectual observation while the other one is the enthusiastic recognition.

In their study, Anderson et al. (2007, p. 18) focused on ‘hotel consumers from Pennsylvania by investigating their travel practices and their inspirations to travel’. The study sectioned the business for the purchasers into three gatherings, for example, visitors going as a family, travellers who rest effectively, and the more established arrangement of holidaymakers. A similar study led by other researchers on the hotel consumers from Taiwan uncovered that ‘the consumers were hesitant to register for a complete visit bundle; rather, the purchasers wanted to have rich visits which had a high calibre as far as procurement of administrations’ (Anbu & Mavuso 2012, p. 315). Customer motivation can be clarified as the greatness of duty, life, and innovation in the piece of the visitor. For some visit supervisors, in the midst of ever slowly expanding more forceful business environment of the late years, figuring out, intends to propel the customers.

A number of past studies on the impact of motivation on consumer and organisational productivity have shown that pull factors of motivation contribute to productivity gains (Dahesh, Nasab & Ling 2012, p. 142). The contribution of the pull motivation schemes to the consumer and organisational satisfaction varies depending on whether the motivation is individual or collective and satisfaction-related. Moreover, Levy and Weitz (2004, p. 152) emphasises, ‘the returns to satisfaction, motivation are larger for ethnic minorities, particularly in the case of women’.

Consumer motivation is viewed as a state of the condition of necessities that impacts a man to participate in a certain activity or movement that has a higher likelihood of conceding him/her a certain level of wanted fulfilment (Ashtiani et al. 2011; Avery 2004). Consumer motivation is a technique concerning inclinations made by people or secondary living beings among substitute types of intentional action (Britton et al. 1999, p. 27). Bass (2005, p. 24) recommended that ‘the current and quick impact on the energy, bearing and constancy of activity can be termed as motivation’. In the same way, Bell (2005, p. 62) implied that ‘inspiration can be offered to the consumers, according to the accompanying systems, the standard or conventional methodology, valid mechanisms, human relations methodology, disguised inspiration, and rivalry’.

Blanchard and Cathy (2002, p. 14) discovered that ‘business chiefs are endeavouring to set up and keep up an environment that is greater for the fulfilment of holidaymakers, who are endeavouring together in gatherings towards the achievement of foreordained objectives’. Annabelle (2006, p. 860) directed a study that ‘concentrated on the examples of gateway for consumer visitors from Germany by focusing on their travel modes, travel destination, length of stay, kind of settlement picked, and excursion recollections’. She discovered that all the mentioned components were instrumental in affecting the visitors to travel (Annabelle 2006). A few studies have been completed to scout the examples of the conduct of the consumers. Aquinas (2006, p. 351) directed a study that ‘tried to investigate on the tourism exercises of the consumers and their conduct with regards to shopping’. The holidaymakers’ travel exercises that were investigated in this study included social tourism, open-air tourism and diversion tourism. The study figured out that the profiles of the travellers were differing as to their likelihood to shop at merchandising channels, their decision of shopping centres, and their wellsprings of data concerning the accessible shopping exercises (Aquinas 2006).

Motivational factors for hotel

A percentage of the issues associated with unmotivated consumers for the Green Hotel incorporate weakening assurance, less happiness and across the board deterrence. If allowed to extend, these issues can diminish profits, aggressiveness and profitability, particularly for little businesses (Ferch & Spears 2011; Farris, Neil & Pfeifer 2010, p. 466). As a general rule, a mixed bag of fluctuated theories and method for consumer motivation have seemed to reach out to the expanded association for money related motivators and representative strengthening (Clawson 2011; Collins 2001; Daft 2005; Gitman 2000). For little consumer endeavours, motivation can be transcendentally difficult where the agents have often worked for a long time for setting up an organization that may be hesitant to give critical powers to others. At the same time, the entrepreneurs ought to be mindful of such downsides.

Consumers for the Green Hotel who have unique thought processes may evaluate a travel destination in the same way, particularly in the event that they are of the supposition that the destination furnishes them with the greatest utility. The theories of consumer motivation can be ‘connected to the mental elements like: needs, goals and objectives, as the speculations give a depiction of the mental components’ (Fields 2010, p. 14). Flint (2012, p. 27) brought out the mental variables of necessities, ‘cravings or objectives actuate an earnest urge in the individual’s brain, which drives him/her to buy products or administrations’. In this manner, ‘inspiration specifically impacts the emotions of the people’ (Fornell 2002, p. 18; Freshwater, Sherwood & Drury 2006, p. 300; Frost & Walker 2007, p. 28). Gallos (2008, p. 57) analysed ‘the critical motivational components that have been brought up by diverse researchers in their studies’. The components include the desire to make tracks in an opposite direction from the day by day projects or work; and the inclination to look for option pleasant encounters (Clawson 2011; Collins 2001; Daft 2005; Gitman 2000).

The concept of consumer satisfaction

One of the theories that explain the adoption of the satisfaction-related motivation is the tournament theory. According to the theory, individuals compete for access prizes in their workplace, such as promotion and motivation increments (Abbas & Asghar 2010, p. 33). Consequently, integrating satisfaction factors among consumers at different levels of management plays an essential role in motivating them to put more efforts in their job roles and responsibilities. Subsequently, the organisation’s satisfaction is improved considerably (Lawler, Porter & Vroom 2009, p. 3). The theory accentuates that satisfaction inequality is directly correlated to organisational and individual satisfaction (Avolio, Walumbwa & Weber 2009, p. 430).

The other theory of motivation approach to satisfaction is the fair satisfaction theory. This theory is linked to the consumers of a hotel. The theory proposes that hotel consumers compare their satisfaction or motivation levels with those of their co-workers or the prevailing market rates to determine whether they are fairly remunerated (Jamali 2007, p. 380). This strategy explains why organisations should assess the internal and external equity in formulating the satisfaction-related motivation schemes (Ashtiani et al. 2011; Avery 2004). This behaviour arises from the fact that consumers have expectations on satisfaction levels and job positions (Britton et al. 1999, p. 27). If they perceive that they are unfairly compensated or paid, they are likely to reduce their effort in executing the assigned job tasks. Moreover, the development of the perception of being underpaid is likely to contribute to negative workplace behaviour amongst consumers. Examples of such behaviours include absenteeism, sabotage, lack of cooperation, and cohesion amongst consumers. This aspect might significantly reduce the overall organisational satisfaction.

The third theory that forms the basis for motivation as a strategy to satiate the Green Hotel consumers entails the efficiency satisfaction theory. The theory holds that motivating consumers’ higher satisfaction improves an organisation’s competitiveness in the market, hence improving the likelihood of attracting and maintaining more consumers (Anbu & Mavuso 2012, p. 315). Furthermore, the theory proposes that high motivation acts as an incentive in promoting consumer satisfaction. A study involving over 8,000 consumers who were selected from the Green Hotels showed that consumers who received high motivation put more effort in their satisfaction. Such consumers are more likely to quit their workplace. Furthermore, a study by Anderson et al. (2007, p. 18) about the satisfaction of the English, German, and Italian football leagues shows that high levels are positively correlated with the respective team satisfaction. Aquinas (2006, p. 351) affirms that ‘this strategy is mainly prevalent in organisations that have adopted individual satisfaction-related motivation systems’. Under such circumstances, consumers understand the apparent consequences that are associated with poor satisfaction.

Theories of consumer satisfaction

Traditional business analysts were the soonest to expound on buyer inspiration throughout the most recent hundred years. They added to another idea of persuading the shoppers and termed it as investigative administration. Their tenets were in light of the idea that the customers were financially urged and were permitted to work keeping in mind the end goal to procure the greatest amount of wages as they can. Their primary presumption was that the monetary increase was the boss help that urged purchasers to perform well in their obligation. They can be said to be fathers of the inspiration speculations, however, their hypothesis has a disadvantage as it considers just money related advantages and disregards other motivational components (Blanchard & Cathy 2002; Fields 2010, p. 14; Frost & Walker 2007, p. 28).

Consumers make their decisions based on the available time. Business chiefs are endeavouring to set up and keep up an environment that is greater for the fulfilment of consumers, who are endeavouring together in groups towards the achievement of foreordained objectives. A few studies have been completed to scout the examples of the conduct of the consumers. The profiles of the consumers are differing as to their likelihood to shop at merchandising channels, their decision of shopping centres, and their wellsprings of data concerning the accessible shopping exercises. Consumers compete for access prizes in their environment, such as promotion and motivation increments. Consequently, integrating ethics among buyers at different levels of management plays an essential role in motivating them to put more efforts in their job roles and responsibilities. Subsequently, the administration’s satisfaction is improved considerably. The satisfaction inequality is directly correlated to the union and individual satisfaction (Ferch & Spears 2011; Farris, Neil & Pfeifer 2010, p. 466).

A consumer is somebody who has purchased an item or service of an organization, vendor or supplier. Be that as it may, from the perspective of consumer loyalty the clarification for the client ought to include the individual, who uses administrations from the organization specifically or by implication. That is more inclined to assume anyone who may purchase any item or administration to be a client. The organization needs an activity to convey their items to clients; this sort of activity is generally called an administration. Customer service has numerous sorts; they are taking into account the kind of item and associations. In diverse spaces, the administration can be characterized in various examples. The administration is an imperceptible operation or execution, it contrasts starting with one association then onto the next association and it doesn’t change any proprietorship (Anbu & Mavuso 2012, p. 315; Maslow 1943, p. 372).

Satisfaction factors of hotel

General hotel satisfaction factors

The other element for utilizing fulfilment is to help the clients with figuring the natural inspiration, which additionally contains acknowledgment, achievement, progression or development, and individual enthusiasm for the occupation. To get the best result, both systems should be executed all the while to spur them; the first step is to give them a chance to feel not unsatisfied in the workplace, then lead them to accomplishment, obligation, and fascinating work, with the goal that they can propel in the work and perform better (Fornell 2002, p. 18; Freshwater, Sherwood & Drury 2006, p. 300). The established researchers’ idea of accomplishment is another hypothesis that has an incredible effect on the administration of inspiration issues and is additionally identified with the cleanliness inspiration hypothesis.

It is watched that for people with more elevated amounts of achievements, inspiration is by all accounts more vested on their occupations. They tend to set high and realistic objectives and need input on how they performed as opposed to on what individuals consider them. Further, they are more inspired by the individual achievements as opposed to distinctions. On the other hand, high accomplishment inspired individuals may not make a viable chief. Additionally, the need for achievements can be told, and the traditional researchers likewise built up some preparation programs for this (Zineldin 2000 p. 20; Yin 2009; Yelkur 2011 p. 110). As specified over, the announcement had shown a percentage of the theories about the shopper inspiration. Diverse researchers hold distinctive perspectives and hypotheses. The chain of importance of necessities, as hypothesized by Maslow, exhibits that the director obliges considering the prerequisites of the workforces and satisfying them to propel (Roy 2012, p. 62; Roth 2008; Saili, Mingli & Zhichao 2012, p. 4300; Rust, Zeithaml & Lemon 2004, p. 112).

Green Hotel satisfaction factors

At the point when the Green Hotel consumer calls attention to the need, he/she continues to distinguish the destination that concedes him/her the most extreme fulfilments. It is extremely helpful for the consumers to find out about the travel destination before deciding to visit. The quest for data identifying the visiting place is persuaded by different possibilities in the commercial centre and the purpose of the visit (Redmond 2010, p. 1). Customers who travel all the time have a more partiality to get data that identifies with the travel item or the travel destination. With this respect, the customers are more energetic to spread the data to other intrigued tourists (Ping 2004, p. 130). The ability of a client to find out the information about the destination is dictated by their past encounters or by the sort of data that they get either specifically or in a roundabout way (Reynolds & Valentine 2011, p. 57). Some consumers ordinarily depend on data from travel offices with the goal to be furnished with the vital data concerning the target site (Reynolds & Arnold 2000, p. 92).

Customers of the Green Hotel have distinctive discernments regarding the sort of travel destination that they desire. Recognition alludes to the route in which the travel customers respect the estimation of the item (Okoro 2012, p. 133; Motavalli 2013, p. 19; Miller 2013, p. 2). The idea of observation stems from the psychological perspective or the behavioural standpoint. In this way, it ought to be noticed that recognition happens as an aftereffect of the procedure of the customer adopting their inspirations. The past investigates concerning consumer motivation uncover that the consumers’ determination and appraisal of travel items are affected majorly by emotional variables (Menon 2006, p. 19). Each consumer is driven by his/her motivational components to move; these motivational elements are both inward and outer and they characterize the consumers’ bits of knowledge with respect to the destination (Matha & Boehm 2008; Mangram 2012, p. 300; Sekaran 2010).

At the point when the Green Hotel customer evaluates the components of the fancied destination, subjective observation is accomplished; then again, passionate recognition depends on the considerations of the Green Hotel consumer with respect to the sought target (Lee 2008, p. 1; Nor 2009). Both recognitions (subjective and passionate) are necessary for detailing modes of view of the consumers’ travel items. Each consumer has an extraordinary yearning to fulfil his/her inspiration where they choose to go. Every customer has an alternate translation of the idea of fulfilment; subsequently, its definition is disparate among different clients. Numerous researchers in their examination articles have connected the meaning of satisfaction to the refinement in the middle of desire and experience (Hair, Bush & Ortinan 2006). Hardester (2010, p. 349) gave a meaning of the tasteful encounter as ‘a piece of the level of the correspondence between the customers’ longings and the encounters that they experience’.

Subsequently, when the post-buy conduct investigation is embraced, it is relied upon to find out whether the consumers have been fulfilled by the visitor items or have been disappointed by the same. The examinations of the post-buy purchaser conduct are identified with the idea of push and draw fulfilments. At the point when the idea of push and force satisfaction is compared to inspiration, both the unmistakable and elusive segments of the post-buy investigation can be analysed (Lim 2014, p. 1). The aim of the consumers to purchase relies upon their intentions that identify with both the behavioural and social standards. The thought processes of the customers rely upon the level of desires that they have concerning the likelihood of accepting a particular conduct and the appraisal of how they respect it (Karamitsios 2013). Keller (1998, p. 78) in his study ‘utilized the hypothesis of the contemplated activity to demonstrate that the goal of the consumers to pick a destination site relies upon the perceived conduct and the past behaviour’.

Relationship between consumers motivation and satisfaction for Green Hotel

Buyer inspiration for the Green Hotel can be clarified as the extent of the dedication, energy, and innovation that an association’s client identifies with their occupations. In all actuality, an assortment of change theories and method for shopper inspiration has seemed, reaching out from expanded inclusion to fiscal motivating forces and customer strengthening (Miller 2013, p. 2; Reynolds & Arnold 2000, p. 92). For little organizations, shopper inspiration can sometimes be difficult. In any case, the entrepreneurs ought to be mindful of such downsides. A portion of the issues associated with unmotivated customers incorporates the decaying spirit, less satisfaction, and far-reaching prevention.

For fostering consumer motivation, the Green Hotel offers a perfect ambience since customers can witness the outcomes of their contributions in a newer method. Notwithstanding expanding intensity, profitability, and exceedingly empowered workers can make the proprietor of a little business to desert operational control on a day-to-day premise and instead concentrate on long-run objectives to build up the business (Lussier 2005; Lovvorn & Chen 2011, p. 280). They thrive in surroundings where they can make a fragile qualification, and where a dominant part of clients of an organization are able and pushing together to make headway with the business. Fittingly organized acknowledgment and financial prize projects are noteworthy, yet not restricted in this mix (Okoro 2012, p. 133; Motavalli 2013, p. 19).

Customer motivation for the Green Hotel can be surveyed by paying respect to the scientific examination of longing, foresight, origination, and fulfilment. Some scholars accentuated on the utilization of measurable devices on tourism (Mangram 2012, p. 300; Sekaran 2010). Subjective decision models are exceptionally proficient in surveying the conduct of the shoppers; such models ultimately rely upon multinomial logit. In the later past, numerous scholarly researchers connected basic models on explores that identify with the appraisal of the consumer motivation (Zineldin 2000, p. 18; Matha & Boehm 2008). There are very critical stages that are included during the time spent on choice making by the consumers. The steps include the pre-decision, the choice, and the post-buy appraisal (Kline 2010; Kolenda 2001; Kotler et al. 2009).

There are various models that explore the concept of consumer behaviour. The macroeconomic model is one of such models, whereby the consumers typically have the intention to expand their utilities to the greatest subject to a mix of requirements, for example, time, salary, and the level of innovation (Kouzes & Posner 2003; Kouzes & Posner 2012). The structural model is whereby the association between the data and yield examined. The professional model implies that the consumer’s judgments are put in an examination (Saxena 2012, p. 40). The established financial hypothesis is the primary premise of the macroeconomic model that investigates the conduct of the consumers. At the point when looking into the interest of reasonable merchandise or administrations, the traditional monetary hypothesis is exceptionally instrumental. What’s more, the established financial theory brings into the centre the confinements that identify with tourism examination.

However, one can claim that associating high motivation with satisfaction poses a risk of consumers losing their job positions in case of failure to achieve the expected satisfaction. This case might adversely affect the extent to which the consumers identify with the firm, despite the past studies. Gallos (2008, p. 57) accentuated that ‘the increase in voluntary consumer turnover might adversely affect the attractiveness of an organisation in the labour market’. Subsequently, the effectiveness and efficiency with which an agency develops long-term competitiveness regarding human capital might be adversely impacted.

Relying on motivation to satisfaction systems might unfavourably affect an organisation’s long-term survival. This view arises from the fact that the business will be subject to economic changes such as inflation. During an economic downturn, the Green Hotel might not sustain motivation increments. Gratton and Jones (2004, p. 410 defined such phenomenon as ‘motivation compression’. The existence of small satisfaction differentials between the high and the poor consumers during periods of an economic downturn might negatively affect the higher consumer’s attitude. For example, users might develop a ‘why bother’ attitude.

Blanchard and Cathy (2002, p. 14) are of the view that ‘linking motivation to satisfaction might complicate the payment schedule that an organisation can adopt’. For example, by continuously increasing the real performer motivation, it is possible for the team to reach the top range. This claim means that making additional motivation increments, despite the consumers earning it, will be substantially more difficult. Therefore, the motivation-to-satisfaction system is not sustainable. The average performers might progress through the motivation scale due to their duration of service in an organisation (Matha & Boehm 2008; Mangram 2012, p. 300; Sekaran 2010; Lee 2008, p. 1; Nor 2009).

Business managers, who identify the small wins of workforces, encourage democratic atmospheres and treat workforces with respect and fairness and make sure that their workforces are extremely motivated (Hughes, Ginnett & Curphy 2012; Jerisat 2004). One association’s manager meditated to line up with thirty capable non-monetary motivations that cost nothing or little to execute. The extraordinarily valuable propelling strengths like time off from work and letters of acclaim improved a customer’s feeling of pride and fulfilment (Hair, Bush & Ortinan 2006). Thusly, an arrangement that fulfils inborn, self-completing individual needs and blends money related prize frameworks may be the most productive buyer stimulator (Hill & Ettenson 2005, p. 88).

Buyer inspiration in the Green Hotel incorporates educating the specialists and remunerating them appropriately according to the great work done. The specialists are persuaded through different measures keeping in mind the end goal to improve their performance; the motivational systems empower the labourers to perform a more prominent employment ceaselessly as they anticipate that vastly improved things will come (Hill & Westbrook 2007, p. 47; Holt & Quelch 2009, p. 70). Buyers in any business oblige to some degree to stay working. For all intents and purposes at all times, the inspiration of the client is satisfactory to empower them to keep working for a foundation. In any case, pointing only for fulfilment is not satisfactory for clients to be natural in an association. A client must be provoked to work for an organization or organization. On the off chance that no boost is available in a client, then that shopper’s distinction for the employment or all exertion will intensify (Kang & Singh 2006, p. 200). Diverse individuals require distinctive inspiration methods as they have differed needs and particulars.

Average motivational plans incorporate identity sort and delicate offer against a hard offer. Careful offer programs have consistent applications, acclaims, enthusiastic claims, and guidance. Then again, hard offer programs have dwarfing trade positions and weight (Kantabutra & Avery 2010, p. 42). For instructive therapists, inspiration has a particular consideration as a result of the fundamental part it has inside understudy information. Regardless, the exact kind of inspiration that is inspected in the committed landscape of training differs subjectively with the most regular sorts of inspiration considered by analysts in different territories. In instruction, inspiration can have a few results on how understudies study and how they perform towards the subject issue. It could be: straight manner toward particular destinations; direct to upgraded vitality and exertion; expand tirelessness in, and start off, execution; enhance intellectual working; setting up what results are motivating; and managing for improved performance.

Research Methodology

Introduction

The methodology is the process of instructing the ways to do the research. It is, therefore, convenient for conducting the research and for analysing the research questions. The process of methodology insists that much care should be given to the kinds and nature of procedures to be adhered to in accomplishing a particular set of procedures or an objective (Wagner 2009). This part includes the research design, the sample and the methods that were used in gathering information. It also contains the data analysis methods, validity and reliability of data and the limitation of the study.

Primary and secondary research

Primary exploration is important for arranging the perceptions or variables, inspecting the variables and producing measurable representations to break down the perceptions. An analyst who uses the essential exploration outline has foreordained information of what’s in store. Additionally, the specialist utilizes information accumulation instruments like polls or other applicable information gathering gear. The sort of information took care of through essential exploration is chiefly in a numerical or measurable configuration. An in number component of the essential exploration is that it is the most effective outline to test theories. Its constraint is that the applicable points of interest of the variables or perceptions may be ignored (Wagner 209).

Then again, a primary examination does not give a full detail regarding the depiction of the exploration process. Not at all like subjective exploration, has the scientist had no clue about what results to expect on the grounds that he/she predominantly depends on perceptions. Essential examination methodology employs a considerable measure of time and requests numerous assets as far as cash and aptitude (Wagner 209).

Quantitative and Qualitative Approach

The quantitative examination approach suggests the usage of accurate techniques, experimental frameworks, and reckoning methods to precisely separate data (Wagner 209). The quantitative methodology goes for utilizing the exploratory and genuine theories and models to separate the data. The quantitative framework favours the hypotheses and conclusions that have been drawn from the subjective methodology. The test frameworks and methodology that are utilized as a part of quantitative theory incorporate construing models and theories, and illustrating instruments for data gathering.

The subjective philosophy is, generally, concerned with the human manners of thinking and the clarifications for such expectations (Wagner 209). The standard addresses that go with subjective philosophy are ‘the reason?’ and ‘how?’ in any case ‘what?’, ‘where?’ and ‘when?’ Concerning this, a master utilizing the subjective approach will tend to use more diminutive samples instead of the greatest examples. Subjective approach completely creates just information that applies to the relegated logical investigation; any additional information is managed as assessments. At the point when hypotheses are drawn from a subjective system, they are attempting through the quantitative technique.

Research Design

There are three sorts of examination outline: exploratory examination, enlightening examination, and causal examination (Wagner 209). Exploratory research principally investigates the way of the issue to create conclusions. In this circumstance, the researcher is in a stunning position to grasp the issue under investigation. The flood of exploratory examination incorporates recognizing the issue and hoping to find the best possible plans and new musings. The exploratory examination is essentially pertinent in circumstances where the structure of the investigation issue is not unmistakable. The meeting is an OK instance of the systems that will be used to aggregate information in this kind of investigation.

This kind of examination is used when the authority plans to perceive the distinctive watched facts in an example or masses. Moreover, the edifying examination is from time to time used by the researcher when the investigator has a previous understanding of the issue under investigation. The causal investigation is the kind of examination whereby there is a sensible structure of the investigation issue. In this circumstance, the examiner is interested in researching the reason sway relationship. The reasons are perceived, destitute down and the level of the effects is assessed (Cooper & Schindle 2006).

Questionnaire Survey

Questionnaires are a pre-arranged course of action on a request that require the respondents to record their reactions as a general rule in solidly portrayed alternatives. Questionnaires can be used to contact the respondents either through the mail or by face to face meeting. Before delineating a survey, there are three norms to pay thought on, these models, consolidate benchmarks of wording, principles of estimation, and the general set up of the study. The rule of the substance includes the substance and purpose behind the request, for instance, the pro needs to fathom the method for variables to be tapped.

On the off chance that a variable is subjective, for instance, customer support where a respondent’s conviction, perceptions, and perspectives are to be measured, the request should draw the estimations and parts of the thoughts. Also, where target variables, for instance, age and pay are tapped, a single direct question would be legitimate. The wording and vernacular are distinctive segments of the guideline of substance, for instance, the tongue of the overview should estimate the level of perception of respondents. Therefore, the choice of words should depend on upon the level of guideline of the respondents.

The rule of estimation encompasses the models to be taken over to ensure that the data accumulated is fitting to test the theories. These norms consolidate request, which includes the similarity of negative request to wind up positive issues, coding, using scales and scaling strategies, and steadfastness and authenticity. Constancy exhibits how relentless and solid the instrument taps the variable. The general set up of the study conceals the preface to respondents, length of the survey, headings for completing and the general appearance of the study (Wagner 210).

Data Collection

This examination primarily depended on essential sources; surveys were utilized to gather the information. Essential information was favoured since it is dependable, helpful and agreeable. The information was gathered by directing a pre-test of the polls. The reviews were issued to an example of 200 respondents; only 169 surveys were filled viably. The information for the study was gathered from the clients of the Green Hotel. The customers were used in light of the way that their profiles fit the setting of this study. Thus, the customers were an amazing choice in light of the way that a robust bit of them had the experience. The individuals’ responses were treated with much security.

Ethical Considerations

In this investigation, the scientist is theorized to have considered all parts of the moral issues. The ethical issues ought to be raised at the suggestion of the examination. The examination should be made and grasped in a way that it energizes quality and dependability. The study staff ought to be instructed of the reason, frameworks and the usage of the investigation. Additionally, they ought to investigate the needs to respect the mystery information and the lack of definition of the respondents. The damage that may be exchanged to the members must be maintained a strategic distance from. As for this study, the data assembled must be secret and not answered by others. The individuals were obliged to share in the examination wilfully, and they had the benefit of not noting inquiries that they saw as uncomfortable. The specialist expected to respect the mystery of the respondents.

Limitations of the study

The expense of leading the review was extravagant. Likewise, there were cases when the respondents gave false and erroneous reactions. The procedure of information accumulation was lengthy and repetitive. What’s more, two or three agents were hesitant to offer some data that was private and risky in the hands of their rivals. This implied an extraordinary test in the examination as the researcher anticipated that would take more chance to find workers who may energetically give out enough data.

Findings, Data Analysis and Interpretation

Characteristics of the sample

In order to understand the demographic information about the participants, the distribution of gender, age, education level, income, and times stayed in the Green Hotel are summarized in the following sections.

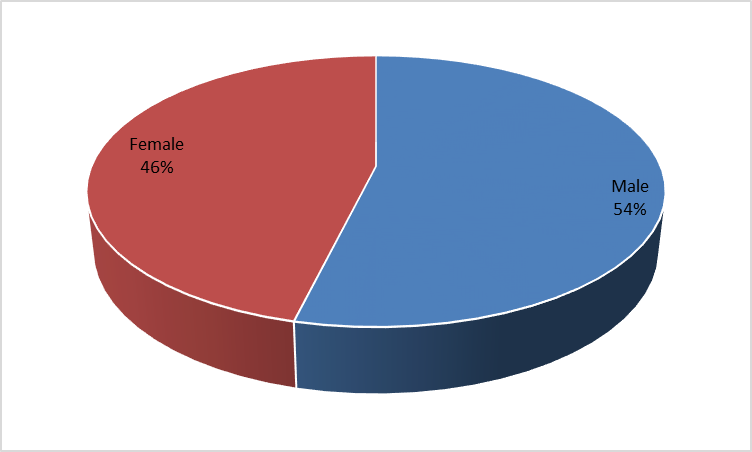

Table 4.1 Gender distribution.

The distribution of gender is summarized in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1, according to the results; there are 78 females and 91 males, composed 46.2% and 53.8% of the sample respectively.

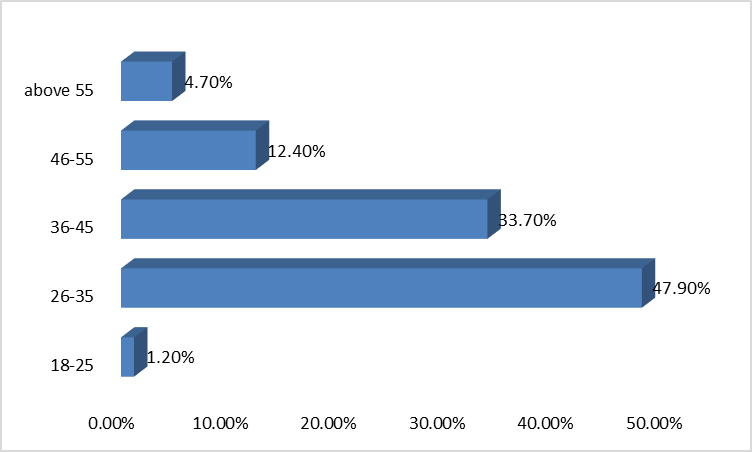

Table 4.2 Age distribution.

The distribution of age is summarized in Table 4.2 and Figure 4.2 above. According to the results, there are 47.9% of the participants aged between 26 and 35, which is the largest proportion, followed by participants aged between 36 and 45, composed 33.7% of the sample, and participants aged between 46 and 55, accounted 12.4% of the sample. Finally, participants aged above 55 or between 18 and 25 composed 4.7% and 1.2% of the sample respectively.

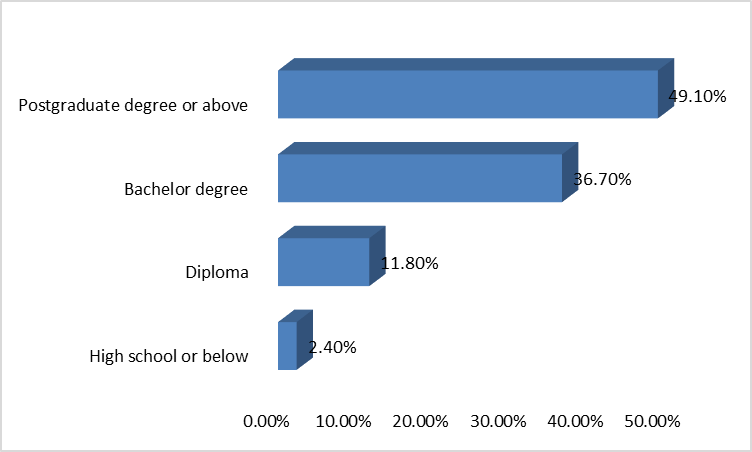

Table 4.3 Education distribution.

In terms of the education level, nearly half of the participants (49.1%) have a postgraduate degree or above, which is the largest proportion, followed by participants who have a bachelor degree, composed 36.7% of the sample, and participants who have a diploma, composed 11.8% of the sample. There are only 2.5% of the participants have high school or below degree.

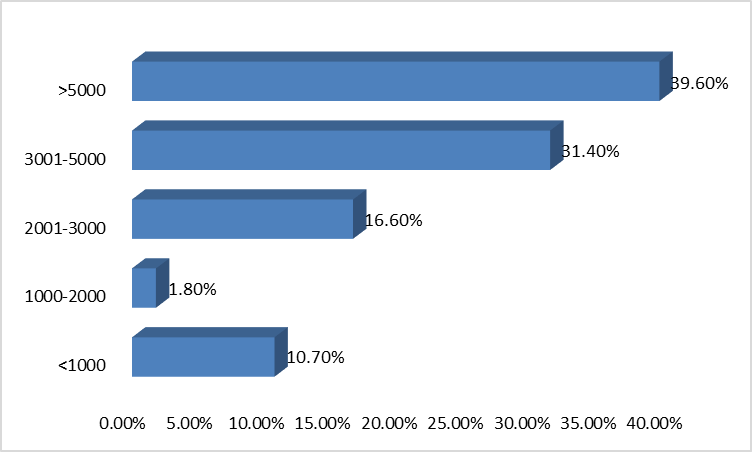

Table 4.4 Income distribution.

Regarding the income of the participants, 39.6% of the participants indicate that they have income above 5000, which is the largest proportion, followed by participants who have income between 3001 and 5000, composed 31.4% of the sample, and participants who have income between 2001 and 3000, composed 16.6% of the sample. There are 10.7% of the participants have income below 1000 and 1.8% of the participants have income between 1000 and 2000.

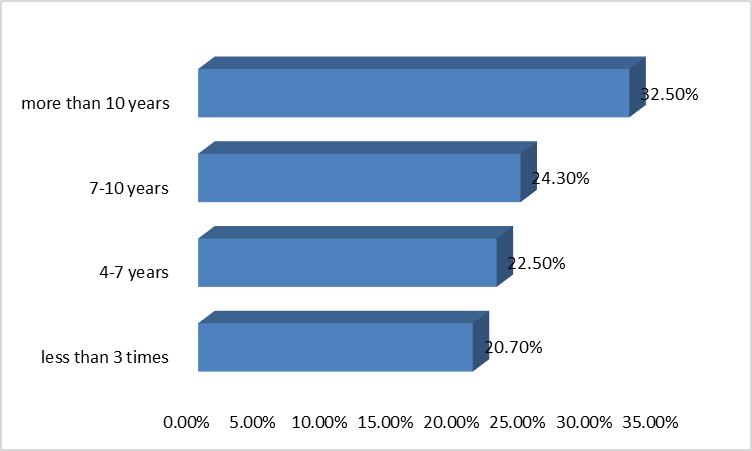

Table 4.5 Times to stay in a Green Hotel.

Table 4.5 and Figure 4.5 above summarized the times the participants have stayed in the Green Hotel. According to the results, 32.5% of the participants have stayed more than 10 times, which is the largest proportion, followed by participants who have stayed between 7 and 10 times, composed 24.3% of the sample, and participants who have stayed between 4 and 7 times, composed 22.5% of the sample. In addition, there are 35 participants have stayed Green Hotel less than 3 times, comprised 20.7% of the sample.

According to the results, the Cronbach’s alpha value of Green Hotel knowledge, environmental concern, fair price, service quality, hotel facilities, subjective norms, and satisfaction are 0.836, 0.817, 0.761, 0.739, 0.898, 0.833, and 0.837, which are all above the minimum requirement of 0.7. In addition, the CICT for individual items are all above the minimum requirement of 0.5 and the Cronbach’s Alpha if deleted for individual items are all below the Cronbach’s Alpha value. These results demonstrate that these items are internally consistent and reliable, and can be used for further analysis.

Green Hotel knowledge frequency analysis

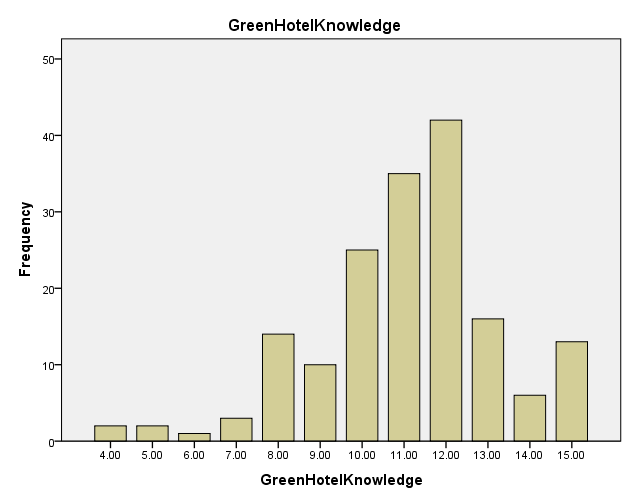

Table 4.7 Green Hotel knowledge frequency analysis.

As can be seen from Table 7 and Figure 7, more than half of the participants are familiar with the Green Hotel knowledge. There are 52.1% of the participants indicate that “Compared to the average person, I am familiar with the hotel’s environmental policies” and 46.2% of the participants indicate that “Compared to my friends, I am familiar with hotels’ green programs”. From the total score of these 3 items measuring Green Hotel knowledge, a large group of participants have a score of 11 or 12. To gain a clearer picture of the participants’ Green Hotel knowledge, the items measuring Green Hotel knowledge were aggregated. The aggregated mean value was 3.69, suggesting that participants have medium level knowledge of the Green Hotel.

Fair price frequency analysis

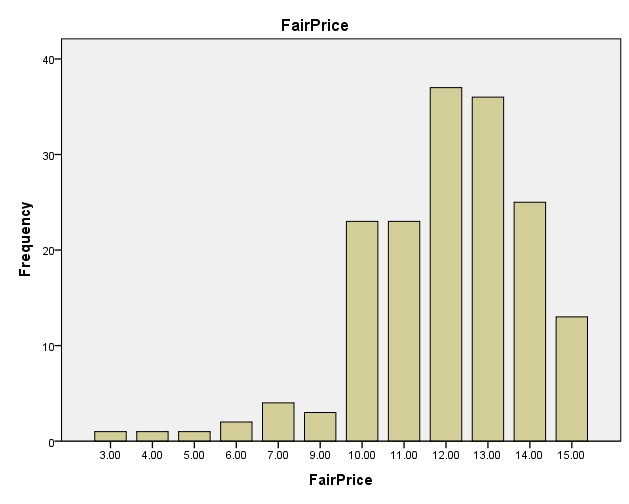

Table 4.9 Fair price frequency analysis.

Table 4.9 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring fair price. According to the results, the majority of the participants agree or strongly agree that “This Green Hotel offers a good service that is worth its rice”, “The prices are acceptable”, and “Compared to the price of other hotels, this Green Hotel charge fairly”. The aggregated mean value of fair price is 3.98, nearly 4, suggesting that participants have a positive attitude towards the fair price of the Green Hotel. Figure 4.9 summarized the score of the items measuring fair price. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 15, indicating a relatively higher level positive attitude towards fair price.

Service quality frequency analysis

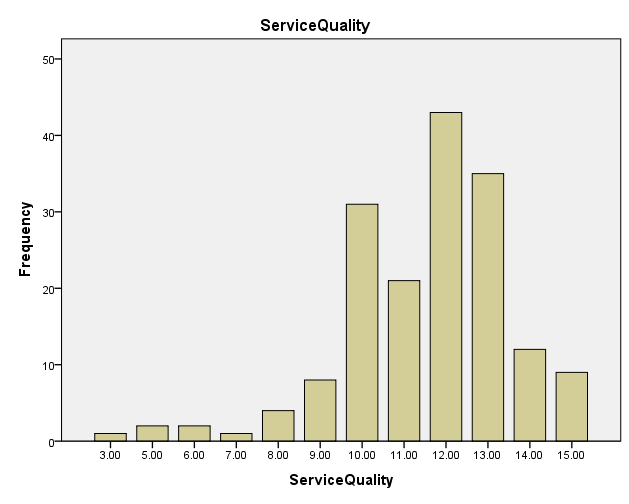

Table 4.10 Service quality frequency analysis.

Table 4.10 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring service quality. According to the results, more than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “The staffs are reliable and helpful”, “The staffs are professional”, and “The staff respond to my inquiries quickly”. The aggregated mean value of fair price is 3.85, suggesting that service quality is at medium to high level. Figure 4.10 summarized the score of the items measuring service quality. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 13, which also indicate a medium to high level service quality perception.

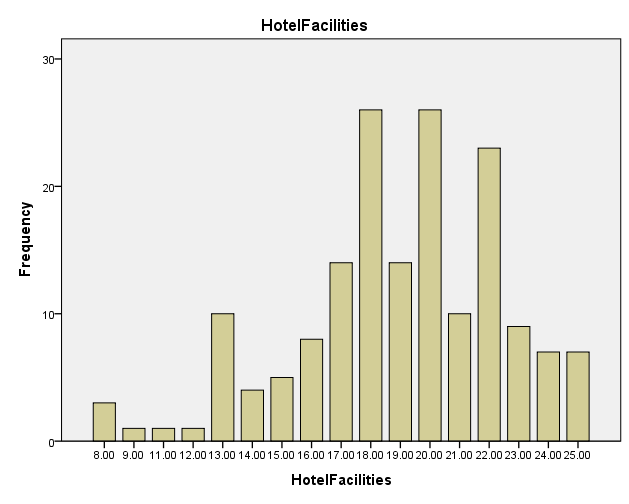

Hotel facilities frequency analysis

Table 4.11 Hotel facilities frequency analysis.

Table 4.11 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring hotel facilities. According to the results, more than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “The hotel temperature is comfortable”, “The hotel environment is comfortable”, “The hotel environment is clean”, “The hotel lighting is appropriate”, “The decoration of the hotel is comfortable”. The aggregated mean value of fair price is 3.79, suggesting that hotel facilities are at medium to high level. Figure 4.11 summarized the score of the items measuring hotel facility. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 18 and 22, which also indicate a medium to high level hotel facility perception.

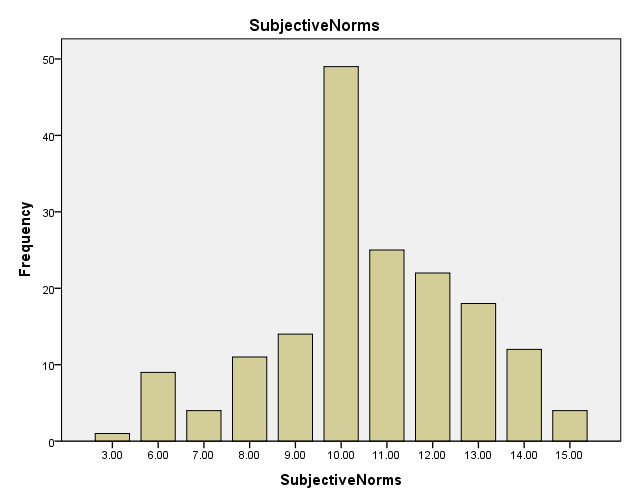

Subjective norms frequency analysis

Table 4.12 Subjective norms frequency analysis.

Table 4.12 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring subjective norms. According to the results, less than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Most people who are important to me think I should stay at a Green Hotel when travelling”, “Most people who are important to me would want me to stay at a Green Hotel when travelling”, “People whose opinions I value would prefer that I stay at a Green Hotel when travelling”. The aggregated mean value of fair price is 3.53, suggesting that the subjective norms are at medium level. Figure 4.12 summarized the score of the items measuring subjective norms. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 11, which also indicate medium level subjective norms.

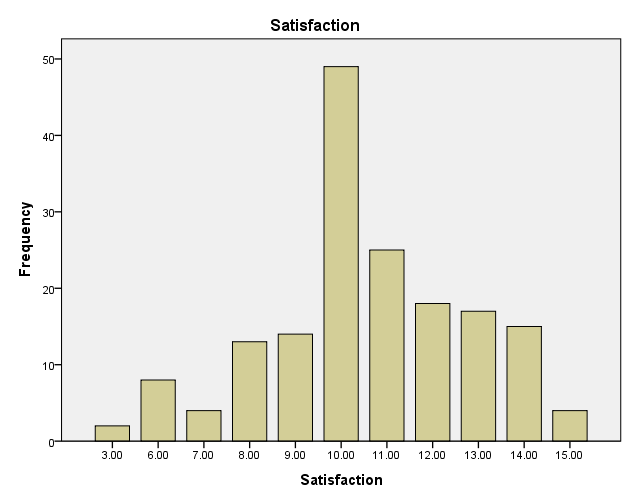

Satisfaction frequency analysis

Table 4.13 Satisfaction frequency analysis.

Table 4.13 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring satisfaction. According to the results, nearly half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Overall, I am satisfied with experience in this Green Hotel”, “I am glad to stay in the Green Hotel again in the future”. The aggregated mean value of fair price is 3.52, suggesting that the subjective norms are at medium level. Figure 4.13 summarized the score of the items measuring satisfaction. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 11, which also indicate a medium level satisfaction.

Correlation analysis

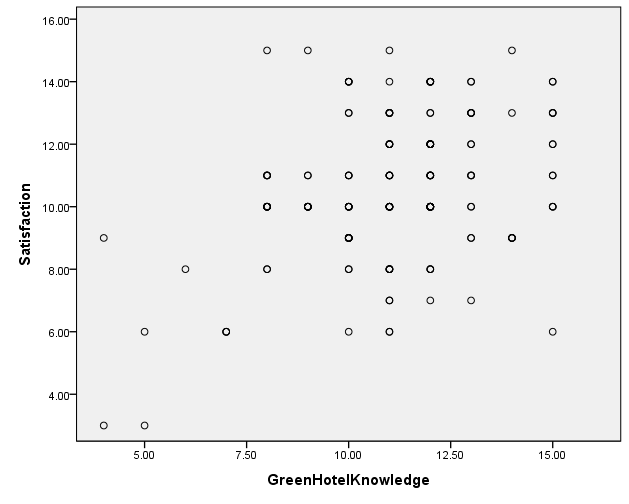

Correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and Satisfaction

In order to check the correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and satisfaction, a scatter plot was first created in order to ensure that there was not a violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity among the data. As seen in Figure 14 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of Green Hotel knowledge and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between Green Hotel knowledge and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in table 4.14 above. The correlation value below 0.3 indicates low level correlation; the correlation value between 0.3 and 0.6 indicates medium level correlation, while the correlation value above 0.6 indicates higher level correlation. As can be seen in Table 4.14, there was a medium positive correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.373, which is significant at 0.01 levels, indicating that higher levels of Green Hotel knowledge are associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table 4.14 Correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and Satisfaction.

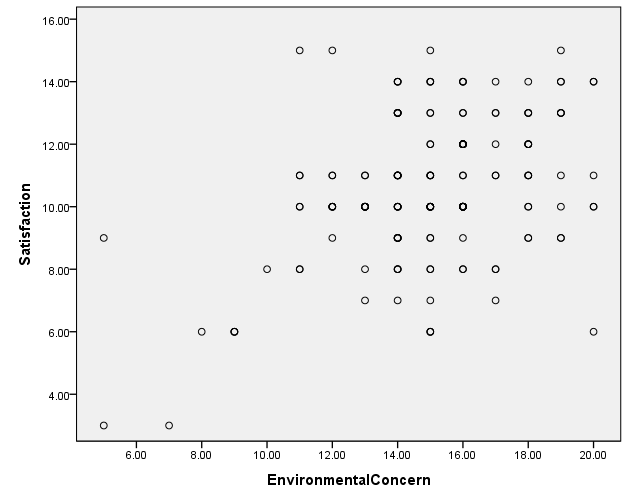

Correlation between Environmental Concern and Satisfaction

In order to check the correlation between Green Hotel knowledge and satisfaction, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.15 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of environmental concern and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between environmental concern and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between environmental concern and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in table 15 below. As can be seen in Table 15, there was a medium positive correlation between environmental concern and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.313, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of environmental concern is associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table 4.15 Correlation between Environmental Concern and Satisfaction.

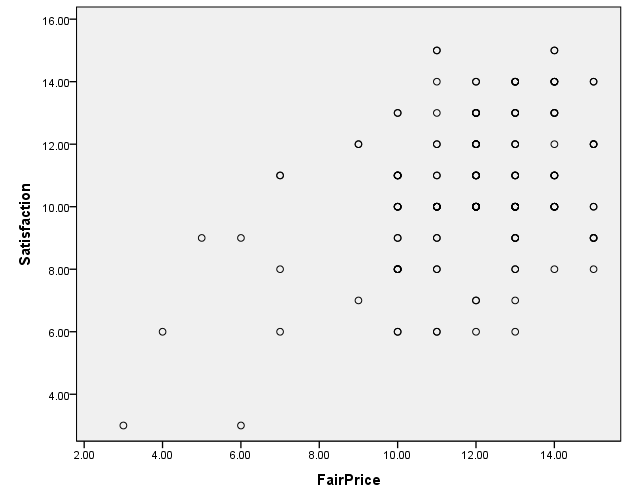

Correlation between Fair price and Satisfaction

In order to check the correlation between a fair price and satisfaction, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 16 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of fair price and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between a fair price and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between fair price and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in table 16 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between a fair price and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.412, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of fair price is associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table 4.16 Correlation between Fair price and Satisfaction.

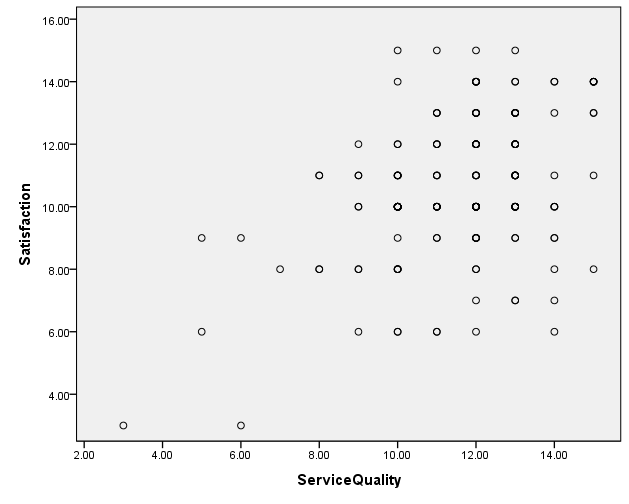

Correlation between Service quality and Satisfaction

In order to check the correlation between service quality and satisfaction, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.17 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of service quality and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between service quality and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in Table 4.17 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between service quality and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.409, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of service quality is associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table 4.17 Correlation between Service quality and Satisfaction.

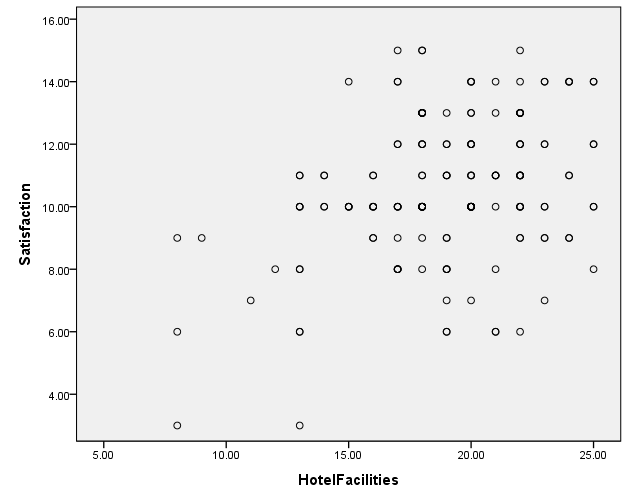

Correlation between Hotel facilities and Satisfaction

In order to check the correlation between hotel facilities and satisfaction, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.18 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of hotel facilities and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between hotel facilities and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between hotel facilities and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in Table 4.18 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between hotel facilities and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.455, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of hotel facilities is associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table18. Correlation between Hotel facilities and Satisfaction.

Correlation between Subjective norms and Satisfaction

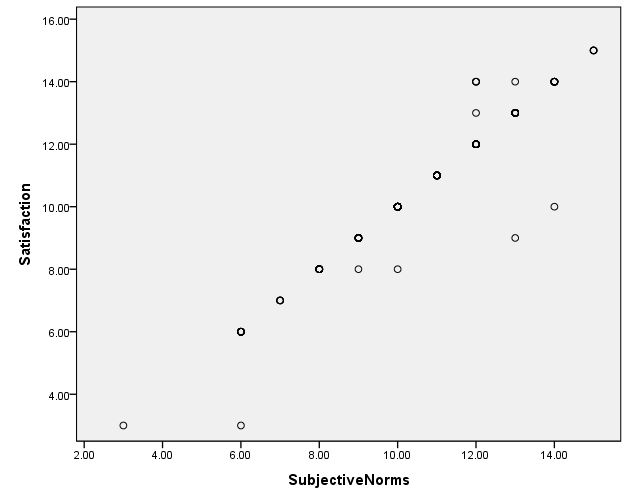

In order to check the correlation between subjective norms and satisfaction, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.19 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of subjective norms and satisfaction and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between subjective norms and satisfaction, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyse the relationship between subjective norms and customer satisfaction. The results are shown in table 19 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a strong positive correlation between subjective norms and satisfaction, with a correlation value of 0.765, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of subjective norms is associated with higher levels of customer satisfaction.

Table 4.19 Correlation between Subjective norms and Satisfaction.

Relationship among variables

Regression analysis is a statistical process for estimating the relationships among variables. More specifically, regression analysis is normally used to understand how the change of independent variables can affect the change of dependent variables (Wagner 2009). The correlation analysis above indicated that there are relationships between subjective norms, hotel facilities, Green Hotel knowledge, fair price, service quality, environmental concern and satisfaction. In order to find out how these variables influence customer satisfaction and which one has the biggest impact, the multiple-linear regression is used.

Table 4.20 Model Summary.

The Adjusted R Square is 0.536, which means that the independent variables of subjective norms, hotel facilities, Green Hotel knowledge, fair price, service quality, and environmental concern can explain 53.6% of the variance of satisfaction.

Table 4.21. ANOVA.

By summarizing the ANOVA table, it can be said that the independent variables of subjective norms, hotel facilities, Green Hotel knowledge, fair price, service quality, and environmental concern can predict the dependent variable of satisfaction at a significance of 0.01, by considering F=411.961.

Table 4.22 Coefficients.

The regression results are summarized in Table 4.22 above. According to the results, there is no collinearity problem among the independent variables as the VIF values for all independent variables are less than 10 and the Tolerance value for all variables are above 0.1. It is found that subjective norms, hotel facilities, Green Hotel knowledge, fair price, service quality, and environmental concern can significantly impact satisfaction, with sig values all less than 0.05. Specifically, subjective norms have the biggest impact on satisfaction, with a standardized coefficient value of 0.437, followed by hotel facilities, with a standardized coefficient value of 0.424 and fair price, with a value of 0.334. The environmental concern has the smallest impact on satisfaction, with a standardized coefficient value of 0.212.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Introduction

This chapter presents the summary of the findings and discussion of the results in accordance to the objectives of this study. Finally, the chapter contains the conclusions and recommendations.

Conclusion

Consumer motivation is viewed as a state of the condition of necessities that impact a man to participate in a certain activity or movement that has a higher likelihood of conceding him/her a certain level of wanted fulfilment The profit and non-profit oriented organisations are increasingly being concerned with the consumer motivation to improve their satisfaction. Consumer behaviour arises from the fact that customers have expectations on satisfaction levels and job positions. If they perceive that they are unfairly satisfied or paid, they are likely to reduce their effort in chasing after the product. Moreover, the development of the perception of being under-satisfied is likely to contribute to the negative demeanour amongst users. Examples of such behaviours include sabotage, lack of cooperation and cohesion amongst clients.

This aspect might significantly reduce the overall organizational satisfaction. Motivating the shoppers’ higher satisfactions improve a business’s competitiveness in the market, hence improving the likelihood of attracting and maintaining more. High satisfaction acts as an incentive in promoting consumer loyalty. High levels of satisfaction are positively correlated with the loyalty and positive bearings of the clients. This strategy is mainly prevalent in societies that have adopted individual satisfaction-related motivation systems. Under such circumstances, clients understand the apparent consequences that are associated with poor satisfaction.