Abstract

A program evaluation and literature review on the imminent positive health impact Community-Based Participatory Research can bring to communities of color were studied. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) has been implemented by public health researchers and other health practitioners to address health disparities and enable community empowerment. Despite the recent growing popularity of CBPR projects, there is not enough effort to continue to maintain long-lasting CBPR projects. This paper attempts to promote and raise awareness of the effectiveness of establishing CBPR linkages with community health practitioners and organizations aiming to achieve health equity.

The methods used in the studies included data collection, project documentation, participant observation, group interviews, closed-ended surveys, written examinations, and randomized controlled group trials. The outcomes demonstrated that a large number of studies addressed a narrow range of health problems, mainly diabetes, and few interventions were described, with the exception of patient education and self-management training. Through the analysis of the situation in the Detroit area, the specifics of the local REACH program were considered, and the problems of the African American and Hispanic communities were highlighted. Appropriate recommendations were proposed for addressing research gaps and targeted work in the region under consideration. The difficulties that African Americans and Hispanics faced concerned not only health disparities but also related issues, particularly social bias. Strengthening community partnerships through engagement with local leaders was suggested as one of the main perspectives. The CBPR conceptual model was utilized as the justification framework. In conclusion, the findings of the literature review and community-based participatory research projects highlight the importance of continuing such partnership efforts to reduce health disparities among minorities and communities of color.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, health disparities, minorities, communities of color, community partnerships, health gaps, African Americans, Hispanics.

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been implemented by public health researchers and other health practitioners to address health disparities and enable community empowerment. Despite the increasing popularity of CBPR programs, there has been little effort to synthesize the literature to evaluate such programs. This paper attempts to promote and raise awareness of the contribution to successful or unsuccessful interventions by offering specific guidelines and utilizing credible and relevant sources.

Health disparities are a severe problem that affects not only the healthcare sector but also social, economic, and other areas. The focus on communities of color and minorities is at the heart of this study since these population groups are more likely than others to have difficulty accessing adequate healthcare services due to their social status and bias ingrained as a result of stereotyping and stigmatization (Johnson-Agbakwu et al., 2020). To describe potential prerequisites for positive developments and evaluate decisions to be made, the research framework is based on the assessment of the available academic literature. Asking an appropriate study question can help focus the direction of the assessment. The search for information involves analyzing relevant sources on the topic of health disparities among social minorities, and the key findings are used as a rationale for making appropriate conclusions and recommendations. In addition, potential gaps in current academic literature regarding the topic raised need to be considered.

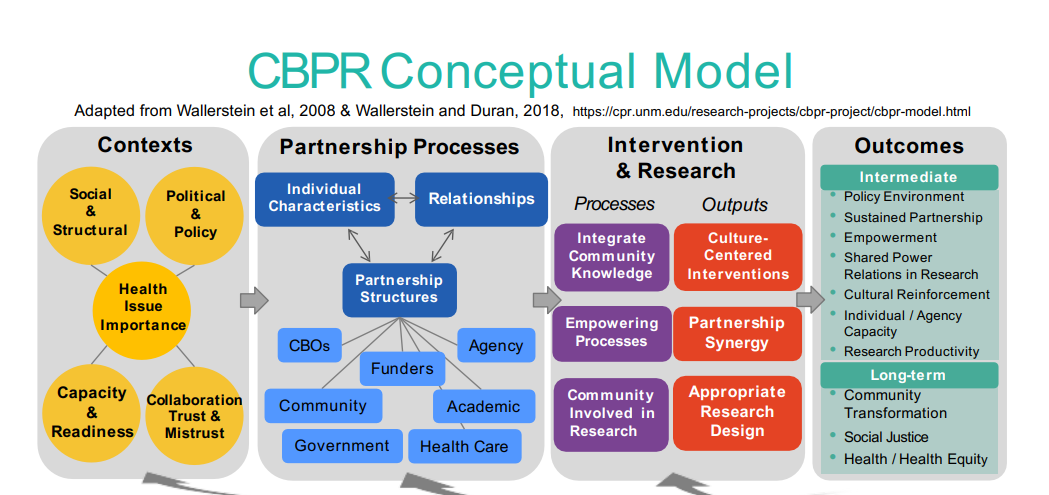

The challenges of social minorities in the Detroit area concerning access to healthcare services are at the root of the study. To suggest relevant actions to be taken, a suitable conceptual framework can be put in place. As such, the CBPR model can be utilized (Figure 1), which Sánchez et al. (2021) describe as a useful framework for constructing a valid assistance program that engages specific stakeholders and highlights intervention steps and potential outcomes.

Direct interaction with the target population, using qualitative methods of data collection and processing of the results obtained, is an essential step towards building a social model in which communities of color and minorities do not face the issue of health disparities and can count on equal access to medical assistance.

Study Question

The analysis of the proposed topic requires the identification of objective criteria that must be taken into account to build a reasonable research framework. As McElfish et al. (2021) state, health disparities among minority communities are associated with socio-economic challenges, namely lack of jobs, low wages, lack of health insurance, and some other constraints. Through the analysis of different barriers, the objective ways of using all available resources can be identified to address health disparities in the target population in the Detroit area. Given all possible factors and limitations, the following question can be asked as the core of the study: What actions can be most effective in addressing health disparities in target communities through appropriate socio-economic and legislative initiatives involving a specific range of stakeholders to expand access to medical services and achieve a long-term healthcare justice vision?

Strategy to Identify Appropriate Literature

To find relevant sources, several selection criteria are essential to address. First, the resources must be relevant to the target population, namely African Americans, Hispanics (Latinos), and other ethnic minorities. For instance, the study by Spencer et al. (2011) reveals health disparities in the two aforementioned population groups, with an emphasis on type 2 diabetes as a target health issue. Keyword search is also a valuable way to find the best evidence base. For instance, using words like “community-based participatory research,” “CBPR,” “health,” and “disparity,” studies by Brush et al. (2019) and Coombe et al. (2018) are identified as valuable guidelines describing appropriate measures taken at community levels.

To address the issue from a geographic perspective, namely, to assess the likelihood of intervention in the Detroit area, the local partnership program needs to be assessed. The targeted project is Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health, or REACH, which works with many families in Hispanic and African American communities, providing educational opportunities and monitoring health statistics (“About REACH-Detroit,” 2018). The use of this resource as one of the supporting sources is justified from the standpoint of analyzing local communities and evaluating strategies for targeted work with the population.

Systematic Review of the Literature

Analyzing the creditable literature by reviewing it and highlighting the key findings is a sound practice to identify general trends in stakeholder activity from a CBPR perspective in the context of the issue of health disparities among minority population groups. Racial and ethnic communities, namely Afro-American and Hispanic, are the target categories. The findings presented may be valuable evidence in support of appropriate intervention procedures and the construction of a valid assistance framework.

General Approaches to Utilizing CBPR

Opportunities for implementing CBPR from the perspective of the topic raised suggest addressing a number of steps aimed at creating sustainable mechanisms for interaction with vulnerable populations. According to Nguyen et al. (2021), this practice is based on the involvement of responsible executors, for instance, medical staff, policymakers, and other specialists who perform the functions of monitoring and implementing healthcare services, and non-academic members, including community members. As the authors note, the main difference between CBPR and traditional interventions is the continuous engagement of the target participants throughout all stages of the work (Nguyen et al., 2021). While taking into account the needs of vulnerable categories, this practice looks justified and reliable. McFarlane et al. (2022) argue that among the positive implications of CBPR implementation, one can point to empirically valid data obtained through the involvement of a large number of participants, as well as a convenient data collection algorithm based on a large amount of information to work with and interpret. Thus, this practice is associated with an objective assessment and the ability to create a sustainable and narrowly focused change process that contributes to collaborating with different stakeholders.

When evaluating the major trends in using the CBPR methodology to address health disparities among target participants, some scholars consider the most common problems that deserve particular attention. Akintobi et al. (2018) state that such chronic health issues as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension are the most common issues reported in communities. In the absence of adequate support from the authorities, the situation is exacerbated by the lack of knowledge about these diseases, and among the perspective areas of work, expanding access to medical assistance is regarded as one of the priorities (Akintobi et al., 2018). In relation to the Detroit area, these findings are also relevant to local communities. As Spencer et al. (2011) argue that the problem of diabetes among ethnic minorities in the region is significant, which is a reason for the specialists from the REACH program to work with the target audience and educate the population about the risks and prevention measures. As a result, while talking about general trends, one might note that communities of color, namely African American or Hispanic, often experience similar problems regardless of the location or level of development of medical services.

CBPR is a practice that can be utilized to address not only physical health concerns. Collins et al. (2018) evaluate the effectiveness of this activity from the perspective of interventions aimed at improving the mental health of community members. According to the authors’ findings, CBPR is a culturally robust and socially just framework for helping target populations cope with mental health problems that occur for various reasons (Collins et al., 2018). However, physical health disparities are a more common problem that some categories of citizens face, especially those whose rights and social opportunities are infringed. Arcury and Quandt (2017) give an example of occupational health disparities associated with difficulties caused by specific jobs and difficult working conditions that cause health issues. Since immigrant workers and other minority citizens often take on hazardous jobs, such as working with pesticides, to earn a living, they need community support and skilled healthcare to avoid hazardous effects (Arcury & Quandt, 2017). Therefore, from the standpoint of intervention significance, physical health disparities experienced by the analyzed populations require an adequate response from medical providers and legislators due to the higher risks minority citizens may experience.

CBPR for African American Community Citizens

As the target groups for this study, African Americans and Hispanics are considered. The African American population is viewed as a minority community, and based on findings from credible sources, the issue of poorer access to health services and, as a result, persistent health disparities persists. For instance, in their study, Brown Speights et al. (2017) assess the problem in the context of the African American female population and define the quality of healthcare provided at the community level. Based on the analysis, the target population’s involvement in mass healthcare quality programs is limited, which, in turn, reflects inequities in the provision of relevant services (Brown Speights et al., 2017). Moreover, even in the context of CBPR, targeting the designated population in the US is not sufficiently effective to warrant comprehensive interventions that can cover the gaps (Brown Speights et al., 2017). In addition, Harvey et al. (2009) draw attention to the higher risks of developing chronic diseases in African American women compared to Hispanics. Thus, CBPR practices should involve the population in question to create effective mechanisms to improve health levels and address the issue of minority health disparities.

CBPR approaches are seen as potentially viable practices that can, nevertheless, be strengthened through complementary measures. For instance, Derose et al. (2018) explore additional engagement methods and note the success of medical providers’ collaboration with religious congregations. African Americans, like Latinos, have an individual self-identity, which is often expressed in cultural aspects, including religion. According to Derose et al. (2018), community-based interventions can be coupled with church-based projects aimed at educating the target population and expanding opportunities for interaction between different stakeholders. The researchers note long-term grants, legislatorial support, and other favorable outcomes of such partnerships that can help expand the understanding of the issue (Derose et al., 2018). From the perspective of optimizing existing health indicators, through such a multi-level practice, African Americans can expect to have their problem more fully covered by different stakeholders, which, in turn, is positively correlated with addressing health disparities. Additionally, along with this population group, Hispanics are also a minority community that can benefit from participating in such programs.

CBPR for Hispanic Community Citizens

Limited access to healthcare services, which Hispanic community citizens experience, has been addressed in a number of academic studies, and the CBPR practice is often discussed as a potentially powerful improvement mechanism. Coffman et al. (2017) note the beneficial effect of neighborhood-based programs in which the Hispanic population is involved. In their study, out of the sample used, only 5.1% of the participants had health insurance, which indicated a poor level of medical assistance (Coffman et al., 2017, p. 121). Regarding personal perceptions, the majority of participants reported dissatisfaction with their health status (approximately 56%) (Coffman et al., 2017, p. 121). In the context of an individual community, these statistics are depressing, and the importance of targeted work with the population is justified. Moreover, given the existing biases regarding the social status of Hispanics, the involvement of not only medical providers but also other stakeholders seems a reasonable solution. Therefore, the population in question is vulnerable in the context of the issue presented and needs the help of responsible interested parties.

The success of applying CBPR in practice can be justified by a real shift in the health indicators of target citizens, particularly a tangible decrease in the level of disparities. In Kia-Keating et al.’s (2017) study, Latinos are the target audience for performing community interventions. The authors pay particular attention to working with young people, explaining that by helping a healthy young population, they can reduce the burden on the healthcare sector in the future and achieve patient-friendly outcomes in the long term (Kia-Keating et al., 2017). A large number of stakeholders is a characteristic feature of such activities. According to the researchers, to achieve positive changes, parents, peer mentors, and healthcare providers are essential interested parties to engage in reducing health disparities among Latino youth through the development and implementation of effective CBPR practices (Kia-Keating et al., 2017). Thus, this strategy of working with minority communities is assessed as potentially effective and one of the few that can address the issue of health disparities from a comprehensive perspective.

Using CBPR for Minorities from the Detroit Area

As with most cases, applying CBPR to minorities of color from the Detroit area requires following traditional steps to achieve effective interventions and accomplish the task of reducing health disparities. Since the target audience includes African American and Hispanic citizens, attention to these groups considered in the academic literature is a priority. Wallerstein et al. (2017) describe the activities of the local urban research center (URC) to identify target participants and organize work to improve the quality of healthcare services that providers in this area guarantee. The authors note that, while relying on geographic criteria and taking into account communities of identity, the local URC will highlight “predominantly African American East Side Detroit and southwest Detroit, with Detroit’s largest percentage of Latinos” (Wallerstein et al., 2017, p. 36). Having such information, stakeholders can establish an effective interaction practice and create a communication algorithm that allows for attracting the necessary patients to achieve the goals set, namely the elimination of health disparities and addressing poor access to medical assistance. As a result, due to geographical division, targeted citizens can be recruited more quickly, which is realized by focusing on community needs.

As specific practical interventions based on CBPR, the academic literature includes some studies. For instance, Coughlin and Smith (2017) note the work of researchers in Detroit’s East Side neighborhood. As a targeted activity, training sessions were conducted with participants, which were aimed at reducing the risk of developing diabetes in citizens and promoting healthy habits, namely good nutrition (Coughlin & Smith, 2017). Considering the aforementioned territorial division of the area, it is obvious that predominantly African Americans were represented as participants. Although, as Coughlin and Smith (2017), a meaningful assessment of the outcomes of the intervention was difficult to undertake due to the lack of funding, the stakeholders involved managed to achieve positive results, namely to form good habits in the population and convey the importance of preventive measures to them. As other interested parties, organizers and researchers engaged local fruit and vegetable vendors by setting up an individual mini market specifically for this purpose (Coughlin & Smith, 2017). Thus, CBPR can have real positive results, as the experience of Detroit’s East Side neighborhood shows, but sufficient planning and funding must be mandatory for a comprehensive assessment of the outcomes.

From the standpoint of the effectiveness of CBPR solutions application in relation to the minority citizens of the Detroit area, in academic sources, not only the quality of the provider-patient interaction is considered as one of the valuable parameters but also the productivity of communication with community leaders. In their study, Parra-Cardona et al. (2020) evaluate stakeholder targeting activities for Hispanics living in the southwest neighborhood. According to the study findings, the authors note that trusting relationships with community leaders contribute to establishing productive activities to address health disparities, particularly in the field of mental health (Parra-Cardona et al., 2020). As the procedures undertaken to address the stated objectives, educational and training activities are described, and the preventive practices communicated to the participants involved benefit their well-being and the well-being of their neighbors (Parra-Cardona et al., 2020). Given these findings, one may note that, despite the challenges of building a unified communication system, community leaders from minority groups are important mediators in the targeted work to eliminate critical health disparities, and to achieve positive CBRP outcomes, there is no urgent need to interact exclusively with all residents of the neighborhood.

Ethnic benchmarking is a useful algorithm to identify potential health disparities between members of different communities and identify the key areas of work that stakeholders need to implement. In Geronimus et al.’s (2020) study, the researchers introduce CBPR and include white, African American, and Hispanic citizens of Detroit as the target audience. One of the critical parameters that the authors evaluate is the level of income, which directly determines the degree of access to healthcare services and the ability to lead a healthy lifestyle (Geronimus et al., 2020). According to the study, the income level of African Americans and Hispanics is lower than that of the white population of the area, which indicates disparities (Geronimus et al., 2020). This information should be taken into account to develop an effective CBPR program because, in addition to practical decisions related to medical aspects, economic nuances are also crucial, although this nuance is not always considered since cultural biases tend to be assessed as the core of the issue in question. The availability of financial resources to purchase insurance or pay for services is a significant factor in creating access and eliminating inequalities.

REACH Program Assessment

To evaluate the effectiveness of CBPR application in the target region, namely the Detroit area, relevant findings are required to be identified, which are presented by scholars working within the aforementioned REACH program. One of the studies related to the involvement of a minority community (Hispanics) is the work performed by Mendez Campos et al. (2018). In this study, the authors evaluate a six-month collaboration between engaged medical professionals and community members to minimize the risk of developing diabetes and educate the population on self-management, namely lifestyle strategies necessary to eliminate the negative consequences of the disease (Mendez Campos et al., 2018). As a conceptual framework, the researchers utilize randomized control interventions to determine whether the outcomes of targeted activities engaging community members are age-different (Mendez Campos et al., 2018). Based on the results obtained, educational activities are more effective for older Hispanics than for younger ones, which is a reason to pay attention to the methods used to interact with youth and help young people address health disparities (Mendez Campos et al., 2018). This study reflects the value of applying CBPR in the context of age differences.

In academic research under the auspices of REACH, the assessment of the challenges that minorities of color face in the Detroit area affects not only physical but also mental health issues. LeBrón et al. (2019) analyze how racial discrimination and diabetes-related stress influence the morale of Hispanics in the community in question. The key objective is to determine whether a correlation exists between a biased society and elevated stress levels exacerbated by comorbid diabetes to provide an objective picture of potential disparities. As a conceptual model and data collection mechanism, LeBrón et al. (2019) use multiple linear regression and conduct surveys among the participants involved to obtain unbiased data and generate appropriate numerical correlations. Based on the results of the study, US-born Hispanics experience depressive symptoms exacerbated not only by diabetes but also by the ethnic discrimination they feel in the community, suggesting a direct relationship between the reported variables (LeBrón et al., 2019). Thus, the health disparities considered in the case of the target population are obvious, and at the community level, stakeholders should promote engagement practices designed to reduce existing stigma to improve minority citizens’ health outcomes.

Follow-up activities performed by community health workers can be part of CBPR programs, and in the Detroit area, the relevant academic base confirms this. For instance, in their study, Spencer et al. (2018) evaluate the targeted work of medical providers in interacting with the minority population (Hispanics) in Detroit and determine how effective educational work is in helping the citizens in question to overcome the negative consequences of diabetes through self-management. Through a randomized study, the authors assess how much more favorable the well-being of patients is after six-month and one-year programs designed to address both the physical and mental manifestations of the disease, namely stressful conditions and depressive moods (Spencer et al., 2018). The key objective to implement is to identify the effectiveness of engaging community health workers to overcome the outcomes of the disease exacerbated by the minority population’s disadvantaged social status. As a result, Spencer et al. (2018) note the productivity of collaborative work and argue that it is beneficial in reducing the physical and mental problems associated with health disparities. These findings support the idea that CBPR is effective in the target region.

Gaps in the Literature

Narrow Circle of Health Problems

Although the topic of using CBPR in working with minority groups is widely described in the academic literature, some gaps are noticeable, which do not allow for fully evaluating the effectiveness of this practice and do not give an opportunity to identify alternative ways to apply this approach. For instance, according to Akintobi et al. (2018), hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are the most common issues associated with health disparities in minorities of color, which are often addressed by engaged community health workers. However, these issues limit the scope of CBPR analysis because, as many other studies show, mental problems associated with depression and stress are a common manifestation of ethnically based bias that the target audience experiences (LeBrón et al., 2019; Spencer et al., 2018). The more areas CBPR programs cover, the more likely they are to successfully address health disparities and solve related issues, such as social stigma. Moreover, the lack of diversity in the evaluation of the application of CBPR does not allow for compiling adequate action plans for different stakeholders, including policymakers and local authorities. Therefore, this gap deserves attention as an incentive for further research work.

Few Drivers of Health Disparities

In the context of evaluating the positive implications of using CBPR for health disparities among minorities of color, academic research tends to address medical issues as prerequisites for related problems. Nonetheless, if one analyzes the probable causes of these disparities, one may find little information about other drivers that, however, are crucial to take into account. For instance, Arcury and Quandt (2017) describe the occupational factors that lead to health disparities in minority communities, particularly the tedious working conditions that employers provide to their immigrant subordinates. Disadvantaged social status, in this case, is a direct prerequisite for bias since inequality in the evaluation of the work of ethnic minorities entails poor access to medical services and, consequently, health issues. In addition, as Arcury and Quandt (2017) state, dangerous jobs that are often entrusted to immigrants often involve threats to these citizens’ well-being and require higher pay from employers, which, however, are not respected. As a result, the existing research sector lacks studies on the different drivers and causes of health disparities among minorities of color to provide a comprehensive picture of the problem and cover various prerequisites for social bias.

Limited Range of Interventions in the Detroit Area

Regarding the issue under consideration in the Detroit area, some gaps in the academic literature can also be noted. The local REACH program addresses the important and well-known mechanisms of helping minorities of color through the implementation of CBPR to enable stakeholders to interact with vulnerable populations. However, when evaluating the current evidence base, one may notice that the bulk of the research is devoted to the analysis of disparities associated with diabetes as one of the main health problems in African Americans and Hispanics (LeBrón et al., 2019; Mendez Campos et al., 2018; Spencer et al., 2011). This health issue is undoubtedly acute and requires the interaction of various interested parties at the community level. Nevertheless, by focusing exclusively on diabetes, researchers overlook other diseases, at least the more common ones, such as hypertension and obesity, which Akintobi et al. (2018) mention. Too narrow a research focus does not allow for revealing all the difficulties that minorities of color in the Detroit area face, and this is a barrier to a comprehensive assessment of the methods of applying CBPR for assessing the existing social bias and performing complex interventions.

Ways to Address the Gaps

While taking into account the aforementioned gaps in the academic literature, it is essential to propose potentially actionable steps aimed at covering as broadly as possible those aspects of the problem that have not been sufficiently analyzed. For instance, to address the issue of too narrow a range of health problems considered by different researchers in relation to the prospects for CBPR, more attention should be paid to evaluating the prospects for applying community-based interventions to address various causes of health disparities, for example, mental disorders. The more potential prerequisites to health disparities are considered, the more extensive evidence base will be compiled, which, in turn, is a significant background for optimizing targeted work with vulnerable population categories. As Corrigan et al. (2017) argue, involved medical providers that work with marginalized African Americans with severe mental disabilities can make a significant contribution to reducing homelessness, thereby addressing an acute social problem and minimizing class inequality. Therefore, expanding the range of health issues to explore in more detail is an adequate solution to enhance understanding of the effectiveness of CBPR and the value of appropriate interventions for targeted minorities of color.

The limited range of drivers considered as prerequisites for health disparities should be addressed through a broader research framework, including not only traditional control-based studies with a limited number of participants and one or two variables but also diverse projects. For instance, the work by Brown and Stalker (2020) presents the analysis of different drivers that, when accumulated among minority communities, exacerbate health disparities. The authors cite social drivers of crime, lack of education, few employment opportunities, residential segregation, and some other issues that may be potential causes of health disparities (Brown & Stalker, 2020). To effectively implement CBPR projects, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the possible prerequisites; otherwise, the analysis is limited, and stakeholders cannot evaluate the full range of possible actions to take to improve the situation. Interviews and surveys can be used as data collection tools, but it is important to cover additional topics so that respondents can answer not only the questions that research teams propose but also describe individual problems and barriers associated with health disparities and accompanying health issues. In this case, the credibility of CBPR projects will be enhanced.

Finally, the research gap that is directly related to the Detroit area should be considered a prospect for future research. Through the REACH program, minorities of color in the region in question receive the support they need through CBPR and interaction with community leaders. Nevertheless, the focus on diabetes as the most common disease associated with health disparities narrows the scope of analysis and does not provide comprehensive information about the problems of the target population in the given area. More attention needs to be paid to other issues, which can also be prerequisites for disparities and relate to inequality and poor access to medical services. As an example of a successful study touching on different nuances, one can review the work by Mehdipanah et al. (2017). The authors emphasize the importance of assessing not only non-communicable diseases like diabetes but also infectious illnesses, such as tuberculosis, and some other indicators that directly reflect the quality of local healthcare (Mehdipanah et al., 2017). For the Detroit area, this research practice will reveal more risk factors and provide a valuable background for future targeted collaboration with communities of color through CBPR.

General Recommendations Based on the Systematic Review

Medical organizations providing public health services should take into account the aforementioned findings to address existing health disparities and minimize risks to vulnerable populations, namely communities of color. Stakeholder partnerships are an important factor in overcoming the current barriers expressed in inequalities and poor access to health services. The CBPR conceptual model (see Figure 1) that Sánchez et al. (2021) cite clearly reflects the processes to take into account and the multi-layered efforts that lead to positive outcomes. Based on the evaluation of the academic literature and the analysis of research gaps, the involvement of policymakers seems to be mandatory for the implementation of all necessary objectives within the framework of CBPR projects. As Sánchez et al. (2021) state, policies related to financial, governmental, and other decisions may be closely related to socio-cultural and other aspects associated with health disparities in minorities of color. Consequently, the more stakeholders are involved in collaborative practices, the higher the likelihood of addressing relevant tasks and constraints at different levels. Therefore, a reliable framework must be formed from the outset to achieve a long-term effect of targeted work and not to miss pressing issues.

From the standpoint of strengthening targeted partnerships, minorities of color should be involved to form a more productive mode of medical providers’ operations and, in parallel, build an efficient system of interaction and education of the population. As the Detroit area assessment results show, both African Americans and Hispanics are in need of skilled care and interventions that can improve their education about how to overcome health disparities (Coughlin & Smith, 2017; Wallerstein et al., 2017). Expanding the range of program coverage is also an urgent task because not only the two mentioned neighborhoods of Detroit can be engaged but also other areas to disseminate the results of CBPR interventions. Since a robust research design is essential for effective partnerships, responsible teams of experts can be formed to promote alternative strategies for collecting and interpreting data from target participants. Both traditional randomized control studies and alternative methods can be utilized, for instance, experimental practices based on transformational communication strategies through digital and other channels. These initiatives can prove to be effective and convenient mechanisms for raising the target population’s awareness of their health disparities and how to deal with them.

Conclusion

As an additional recommendation in regards to increasing the sustainability of CBPR in the Detroit area, promoting closer engagement with the local authorities may be a worthwhile step to reduce health disparities in the populations under consideration. While keeping in mind the aforementioned conceptual framework, various stakeholders are involved in targeted activities to strengthen the health system and help vulnerable communities. Berry (2020) gives an example of the involvement of the city council in matters of public medical services and points to privatization as one of the potential solutions to strengthen the work of hospitals. According to the author, due to financial constraints, the local authorities cannot control the performance of such facilities, which, in turn, inevitably affects patient outcomes (Berry, 2020). Medical provider partnerships with authorized council representatives have the potential to improve targeted outreach to minority communities and create an inclusive and supportive environment free from any forms of bias. It is of critical importance to analyze the proposed recommendations to address all the aspects of CBPR projects as comprehensively as possible and to achieve the competent allocation of the city’s resources to spend on helping the population.

In conclusion, this article is another piece of work that highlights the imminent need to continue to press on the need for community-based participatory research in marginalized and minority communities. CBPR is a key component to addressing health disparities that otherwise would remain a heavy burden. While taking into account the presented findings and views of scholars on the aspects of promoting this practice in minority communities, relevant trends are identified, and specific recommendations are given. The conceptual model that describes all the steps required to achieve the objectives of CBPR projects reflects a wide range of tasks that stakeholders have to deal with to perform effective interventions and maintain productive partnerships. The number of academic sources involved with different research methods and data collection mechanisms proves the relevance of the topic and confirms the value of performance optimization to strengthen assistance to vulnerable populations in overcoming health disparities and related problems associated with social discrimination and bias. Based on the conducted systematic review, relevant findings are reviewed regarding interventions in the Detroit area as a target region, and research gaps are described with potential recommendations to correct them.

For minorities of color, namely African Americans and Hispanics, the findings from the reviewed sources, including local Detroit research projects sponsored by REACH, confirm too narrow a focus of CBPR interventions. Few diseases are considered in the context of health disparities, and an insufficient variety of supportive solutions is offered; typically, education and self-management are the main practices that involved medical professionals promote. In addition, the participation of the local authorities in partnership work is weak, which is caused by the lack of funding and the inability to effectively control the public health sector. More stakeholders’ attention should be paid to the different prerequisites for health disparities among vulnerable communities, as well as to alternative CBPR practices that include various mechanisms of communication with the target population. Strengthening partnerships through interaction with community leaders is another significant task to implement within the framework of this work. The proposed initiatives are potentially effective steps to improve the situation and help minorities of color overcome health disparities or at least minimize them.

References

About REACH-Detroit. (2018). The Regents of the University of Michigan. Web.

Akintobi, T. H., Lockamy, E., Goodin, L., Hernandez, N. D., Slocumb, T., Blumenthal, D., Braithwaite, R., Leeks, L., Rowland, M., Cotton, T., & Hoffman, L. (2018). Processes and outcomes of a community-based participatory research-driven health needs assessment: A tool for moving health disparity reporting to evidence-based action. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 12(1 Suppl), 139-147. Web.

Arcury, T. A., & Quandt, S. A. (2017). Community-based participatory research and occupational health disparities: Pesticide exposure among immigrant farmworkers. In F. T. Leong, D. E. Eggerth, C.-H., Chang, M. A. Flynn, J. K. Ford, & R. O. Martinez (Eds.), Occupational health disparities: Improving the well-being of ethnic and racial minority workers (pp. 89-111). American Psychological Association. Web.

Berry, Y. (2020). Paving a path to privatization: The history of health care in Detroit. Johns Hopkins University, 1(1), 21785.

Brown, M. E., & Stalker, K. C. (2020). Consensus organizing and community-based participatory research to address social-structural disparities and promote health equity: The Hope Zone case study. Family & Community Health, 43(3), 213-220. Web.

Brown Speights, J. S., Nowakowski, A. C., De Leon, J., Mitchell, M. M., & Simpson, I. (2017). Engaging African American women in research: An approach to eliminate health disparities in the African American community. Family Practice, 34(3), 322-329. Web.

Brush, B. L., Mentz, G., Jensen, M., Jacobs, B., Saylor, K. M., Rowe, Z., Israel, B. A., & Lachance, L. (2019). Success in long-standing community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnerships: A scoping literature review. Health Education & Behavior, 47(4), 556-568. Web.

Coffman, M. J., de Hernandez, B. U., Smith, H. A., McWilliams, A., Taylor, Y. J., Tapp, H., Schuch, J. C., Furuseth, O., & Dulin, M. (2017). Using CBPR to decrease health disparities in a suburban Latino neighborhood. Hispanic Health Care International, 15(3), 121-129. Web.

Collins, S. E., Clifasefi, S. L., Stanton, J., Straits, K. J., Gil-Kashiwabara, E., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Nicasio, A. V., Andrasik, M. P., Hawes, S. M., Miller, K. A., Nelson, L. A., Orfalym V. E., Durna, B. M., & Wallerstein, N. (2018). Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. American Psychologist, 73(7), 884-898. Web.

Coombe, C. M., Schulz, A. J., Guluma, L., Allen III, A. J., Gray, C., Brakefield-Caldwell, W., Guzman, J. R., Lewis, T. C., Reyes, A. G., Rowe, Z., Pappas, L. A., & Israel, B. A. (2018). Enhancing capacity of community-academic partnerships to achieve health equity: Results from the CBPR partnership academy. Health Promotion Practice, 21(4), 552-563. Web.

Corrigan, P. W., Kraus, D. J., Pickett, S. A., Schmidt, A., Stellon, E., Hantke, E., & Lara, J. L. (2017). Using peer navigators to address the integrated health care needs of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 68(3), 264-270. Web.

Coughlin, S. S., & Smith, S. A. (2017). Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and prevent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(2), 259-268. Web.

Derose, K. P., Williams, M. V., Branch, C. A., Flórez, K. R., Hawes-Dawson, J., Mata, M. A., Oden, C. W., & Wong, E. C. (2018). A community-partnered approach to developing church-based interventions to reduce health disparities among African-Americans and Latinos. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6(2), 254-264. Web.

Geronimus, A. T., Pearson, J. A., Linnenbringer, E., Eisenberg, A. K., Stokes, C., Hughes, L. D., & Schulz, A. J. (2020). Weathering in Detroit: Place, race, ethnicity, and poverty as conceptually fluctuating social constructs shaping variation in allostatic load. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(4), 1171-1218. Web.

Harvey, I., Schulz, A., Israel, B., Sand, S., Myrie, D., Lockett, M., Weir, S., & Hill, Y. (2009). The Healthy Connections project: A community-based participatory research project involving women at risk for diabetes and hypertension. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 3(4), 287-300. Web.

Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E., Ali, N. S., Oxford, C. M., Wingo, S., Manin, E., & Coonrod, D. V. (2020). Racism, COVID-19, and health inequity in the USA: A call to action. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9, 1-7. Web.

Kia-Keating, M., Capous, D., Liu, S., & Adams, J. (2017). Using community based participatory research and human centered design to address violence-related health disparities among Latino/a youth. Family & Community Health, 40(2), 160-169. Web.

LeBrón, A. M., Spencer, M., Kieffer, E., Sinco, B., & Palmisano, G. (2019). Racial/ethnic discrimination and diabetes-related outcomes among Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(1), 105-114. Web.

McElfish, P. A., Rowland, B., Porter, A., Felix, H. C., Selig, J. P., Semingson, J., Willis, D. E., Smith, M., Riklon S., Alik, E., Padilla-Ramos, A., Jasso, E. Y., & Zohoori, N. (2021). Use of community-based participatory research partnerships to reduce COVID-19 disparities among Marshallese Pacific Islander and Latino communities – Benton and Washington counties, Arkansas, April-December 2020. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18, 210124. Web.

McFarlane, J. S., Occa, A., Peng, W., Awonuga, O., & Morgan, S. E. (2022). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) to enhance participation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials: A 10-year systematic review. Health Communication, 37(9), 1075-1092. Web.

Mehdipanah, R., Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., Gamboa, C., Rowe, Z., Khan, M., & Allen, A. (2017). Urban HEART Detroit: A tool to better understand and address health equity gaps in the city. Journal of Urban Health, 95(5), 662-671. Web.

Mendez Campos, B., Kieffer, E. C., Sinco, B., Palmisano, G., Spencer, M. S., & Piatt, G. A. (2018). Effectiveness of a community health worker-led diabetes intervention among older and younger Latino participants: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Geriatrics, 3(3), 47. Web.

Nguyen, T. T., Wallerstein, N., Das, R., Sabado‐Liwag, M. D., Jernigan, V. B. B., Jacob, T., Cannady, T., Martinez, L. S., Ndulue, U. J., Ortiz, A., Stubbs, A. W., Pichon, L. C., Tanjasiri, S. P., Pang, J., & Woo, K. (2021). Conducting community‐based participatory research with minority communities to reduce health disparities. In I. Dankwa-Mullan, E. J. Pérez-Stable, K. L. Gardner, X. Zhang, & A. M. Rosario (Eds.), The Science of Health Disparities Research (pp. 171-186). John Wiley & Sons. Web.

Parra‐Cardona, R., Beverly, H. K., & López‐Zerón, G. (2020). Community‐based participatory research (CBPR) for underserved populations. In K. S. Wampler, R. B. Miller, & R. B. Seedall (Eds.), The handbook of systemic family therapy (pp. 491-511). John Wiley & Sons. Web.

Sánchez, V., Sanchez‐Youngman, S., Dickson, E., Burgess, E., Haozous, E., Trickett, E., Baker, E., & Wallerstein, N. (2021). CBPR implementation framework for community‐academic partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3-4), 284-296. Web.

Spencer, M. S., Kieffer, E. C., Sinco, B., Piatt, G., Palmisano, G., Hawkins, J., Lebron, A., Espitia, N., Tang, T., Funnell, M., & Heisler, M. (2018). Outcomes at 18 months from a community health worker and peer leader diabetes self-management program for Latino adults. Diabetes Care, 41(7), 1414-1422. Web.

Spencer, M. S., Rosland, A. M., Kieffer, E. C., Sinco, B. R., Valerio, M., Palmisano, G., Anderson, M., Guzman, J. R., & Heisler, M. (2011). Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2253-2260. Web.

Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J. G., & Minkler, M. (Eds.). (2017). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.