One of the foremost characteristics of Classical artistic style, associated with Greco-Roman antiquity, is the fact that it is being concerned with the celebration of bodily perfection.

This can be explained by the fact that Greco-Roman artists of the era were convinced of the existence of dialectical relationship between the concepts of aesthetic/intellectual finesse, civil virtuousness and the notion of physical health, as such that organically derive out of each other.

According to Yalouris (1960): “(Greco-Roman) statues of gods and heroes exemplified youthful strength and tended to show episodes that emphasized their physical prowess… Simply clad, or naked like the hero, the noble and free citizen was represented by a body of marvelous proportions and calm expression” (p. vii).

The earlier mentioned aesthetic feature of Greco-Roman sculptures (and Classical art, in general) appears to be the consequence of the fact that, throughout the course of Classical period of Western history, the continuous development of philosophic thought has not been affected by any form of ideological/religious oppression, whatsoever.

In its turn, this naturally prompted Classical thinkers to promote an idea that the physical constitution of one’s body is indeed being reflective of his or her mind’s workings, which is exactly the reason why most survived Classical sculptures simultaneously emanate the spirit of physical strength and intellectual self-confidence.

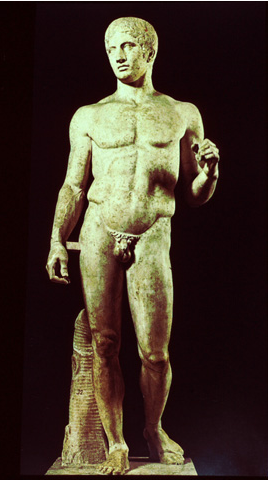

The validity of this suggestion can be well illustrated in regards to the marble sculpture of ‘Spearbearer Polykleitos of Argos’ (440 B.C). As it can be seen on the picture, the depicted ‘Spearbearer’ appears to be no stranger to physical exercises. His naked body is being perfectly proportionate, in anatomic sense of this word.

The expression on man’s face radiates calmness and the strength of his resolution to remain in full control of its destiny. This, once again confirms the soundness of an idea that Classical art cannot be discussed outside of what happened to historical/intellectual preconditions for this particular artistic style to thrive, such as the continuous progress in variety of empirical sciences (medicine, anatomy) and the absence of ideological obstacles, on the way of this progress.

However, the adoption of Christianity by Romans in 4th century A.D. produced a powerful blow on the ideals of artistic Classicism, as these ideals were absolutely inconsistent with the dogmas of newly adopted religion from Middle-East. After all, the very essence of Christian doctrine is being concerned with the ‘destruction of flesh’ as the pathway to heaven. This was exactly the reason why, after having obtained legal status in Roman Empire, Christians instantaneously preoccupied themselves with destroying what they considered the artistic emanations of ‘paganism’.

As it was pointed out by Bourgeois (1935): “Christianity strived to annihilate the antique – classical sculptures were smashed as idols in untold numbers as being too dangerous to the new faith to survive” (p. 7). Therefore, it does not come as a particular surprise why, during the course of Dark Ages, when Christianity enjoyed an absolute dominance in Western intellectual domain, the very concept of art undergone a dramatic transformation.

The Classical ideals of bodily perfection, embodied in Greco-Roman antique sculptures, were replaced by the ideal of ‘Christian humility’, which is why the images of Jesus and countless Christian saints, depicted on Catholic and Orthodox icons through 5th-14th centuries, radiate the spirit of physical inadequacy, suffering and death.

Nevertheless, once Christianity’s ideological grip onto Western societies began to weaken, it resulted in gradual resurrection of Classical aesthetic ideals –hence, the artistic/cultural movement of Renaissance, which from French literally translates as ‘revival’. Just as it used to be the case with Classical Greco-Roman art, Renaissance art celebrates bodily beauty and establishes dialectically predetermined links between individual’s physical appearance and the extent of his or her existential adequacy. This is the reason why Renaissance artistic masterpieces (particularly sculptures) are not only being anatomically accurate but also charged with the same humanist spirit, as it is being the case with Classical examples of art.

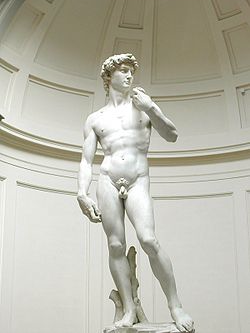

The legitimacy of this statement can be explored in relation to Michelangelo’s sculpture ‘David’. Whereas; medieval artists used to depict David as having already accomplished victory over Goliath, Michelangelo’s David is only getting ready to a fight. David’s facial features leave no doubt as to the fact that, prior to beginning to work on this sculpture;

Michelangelo closely studied Greek depictions of God Apollo – narrowed skull, particularly high forehead, blond curly hair, protruding chin. The proportions of David’s naked body are close to ideal. Just as it is being the case with ‘Spearbearer’, Michelangelo’s ‘David’ appears to be in perfect physical shape.

Thus, it is not only that David’s posture alone provides spectators with the insight on the strength of his resolution to fight Goliath – while observing ‘David’; they get to realize where such his resolution originates. Just as ancient Roman and Greek philosophers, Michelangelo was well aware that healthy spirit could only reside in one’s healthy body.

While referring to this particular Michelangelo’s artistic work, Murray and Murray state: “Michelangelo’s choice of subject was not the battle itself but nude studies of the warriors preparing to fight: it was a hymn to the perfection of male beauty and virility” (p. 241). Therefore, there can be few doubts as to the fact that Classical and Renaissance artistic styles are not only being closely related – the latter is nothing but logical continuation of the first.

The same can be said about many latter Western artistic styles, which have clearly been influenced by Renaissance art, such as Romanticism and Realism. For example, just as it is being the case with Renaissance paintings, most Realist and Romanticist paintings feature perceptual depth, realistic coloring and the anatomic life-likeness of depicted human figures.

It goes without saying, of course, that despite Renaissance art being concerned with exploration of the same aesthetic ideals as it used to be the case with Classical art, it nevertheless operates with Christian themes. Apparently, during the course of 14th-15th centuries, the power of the Church was still considerable, which is why such prominent Renaissance artists, such as Giotto di Bondone, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, had no choice but to utilize Biblical motifs as thematic framework for their art.

This art’s relation to Christianity, however, appears utterly superficial, as the very essence of how of how Biblical fables are being represented by earlier mentioned artists stands in striking opposition to Christian worldview.

Therefore, it will only be appropriate to conclude this paper by reinstating once again that, despite the fact that there is a gap of thousand years between the historical periods of Greco-Roman Classicism and Renaissance, these two periods are being interrelated in rather inseparable manner.

This point out to the fact that the apparent similarity between Classical and Renaissance artistic conventions is not being accidental, but as such that derives out of the very nature of how intellectually liberated Westerners assess the aesthetic significance of surrounding reality.

In its turn, this also explains why even today, both artistic styles are being commonly regarded as archetypical of the Western sense of artistic finesse.

References

Bourgeois, S. (1935) Italian Renaissance sculpture. Parnassus, (7)3, 7-8.

Murray, P. & Murray, L. (1963). The art of the Renaissance. New York: Praeger.

Sporre, D.J. (2009). Perceiving the arts: An introduction to the humanities (9th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Yalouris, N. (1960). The sculpture of the Parthenon. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society.