Introduction

Hypertension is a common condition affecting an individual’s arteries. According to Flack and Adekola (2020), an individual can be diagnosed with this condition if their blood pressure is above 140/90 mmHg. The ailment is prevalent worldwide and can be severe if not treated promptly.

According to Chobufo et al. (2020), approximately 50% of those aged 20 years and older in the United States are affected by hypertension, with a mere 39.64% of those receiving medication demonstrating successful management of their condition. An individual’s susceptibility to the ailment can be increased if they are overweight, drink too much alcohol, eat more salt, and have a lot of stress (Flack & Adekola, 2020). However, the disease can be managed through antihypertensive medications, lifestyle modifications, and treatment adherence.

Patient Background

The client, Wilhelmina, aged 74 years, came into the hospital for the fourth CHF visit with her granddaughter accompanying her. She had a stroke but is still being monitored by neurologists. The client also had reduced ejection fraction, heart failure, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea. She is not on ACE or ARNI because she has a history of angioedema with lisinopril and has a CAD stent in situ that was placed in 2012.

In 2022, a transthoracic echocardiogram was put in place, and the ejection fraction was 30-35, indicating a trace of mild mitral regurgitation. The same procedure was done in 2023 and yielded similar results. Myocardial perfusion imaging was done in 2022 and indicated no ischemia. However, it was repeated the following year. It displayed a medium-sized apical inferior defect with minimal reversibility observed at the basal and mid-inferior-lateral wall with an ejection fraction of 36%.

Left heart catheterization was done on 3/13/23, with an impression of markedly tortuous coronary and right innominate anatomy. A patent mid-right coronary artery stent was put in place, and there was mild residual CAD in large epicardial coronaries. Left anterior descending artery and distal right posterior descending aorta coronary artery diseases were tortuous, and small caliber vessels were recommended for medical therapy. The assessed and documented left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 10 mmHg.

Ms. Wilhelmina was hospitalized in 2022 due to acute HF and CVA. EF was now down to 30% and was expected in 2022. The nonstress test showed no acute ischemia. The client, after feeling better, was discharged with Lifevest and not on ACE due to a history of angioedema with lisinopril. On 24 January 2023, Wilhelmina presented to the hospital with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Upper endoscopy was performed and revealed the client has gastroduodenitis and esophagitis. She was started on Protonix 12 hourly, and from the 22nd to the 25th of May, she experienced an altered mental status. She suffered urinary tract infections, as unraveled by the investigations, and she was then treated with antibiotics.

At present, the patient claims to have no active symptoms, that there is no lower limb edema, nor has she gained any extra weight, developed syncope or dizziness, palpitation, or cerebral palsy. She has good blood pressure values and a BNP of 24. She continues to wear a life vest and has a follow-up echo scheduled for 10/27/2023. From her history, she is allergic to morphine and Lisinopril since, when ingested, she can develop angioedema and anaphylaxis.

Moreover, kidney failure has been reported by her daughter as a complication of care. The current outpatient medications include amlodipine 5mg daily, aspirin 81 mg daily, atorvastatin 80 mg nocte, beclomethasone HFA 40 mcg/actuation inhaler as needed, and benzonatate 100 mg whenever necessary. She is also on ergocalciferol one cap, furosemide 40 mg, hydrocodone-acetaminophen 10-325 mg six hourly, promethazine 25 mg PRN, and JANUVIA 100 mg daily.

Vitals

Lab Tests on 3/3/23

Lab Tests on 4/1/23

Lab Tests 6/12/23

Lab Tests 8/12/23

Pathophysiology

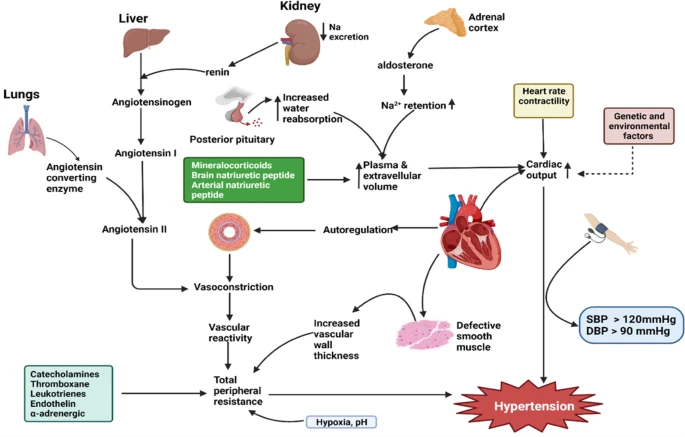

Due to the interplay of numerous systems and mechanisms, the etiology of hypertension is complex. Among the key factors influencing this process is impaired natriuresis of kidney pressure, which significantly contributes to the onset of hypertension. Elevated blood pressure induces the kidney to increase sodium and water excretion, which reduces blood volume and subsequently diminishes blood pressure (De Bhailis et al., 2022). In a renal pressure natriuresis failure, the kidneys’ increased fluid and sodium retention leads to increased blood volumes. This factor contributes to the development of hypertension, as shown in Figure 1.

An additional critical element contributing to hypertension is the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This mechanism is critical for the regulation of blood pressure. The kidneys secrete renin in response to a decrease in blood pressure; this hormone stimulates the synthesis of angiotensin II and the release of aldosterone (De Bhailis et al., 2022). Angiotensin II increases peripheral resistance by constricting blood vessels, as illustrated in Figure 1. In contrast, aldosterone increases blood volume by stimulating the kidneys’ reabsorption of sodium and water. Hyperactivity of the RAAS can lead to sodium-water retention and excessive vasoconstriction, both of which are associated with elevated blood pressure.

A conspicuous characteristic of hypertension is an elevation in total peripheral resistance (TPR), a metric used to quantify the resistance encountered by blood as it traverses the arteries and arterioles, which are minor branch vessels of arteries leading to the capillaries. Blood vessels constrict during smooth muscle cell contraction, increasing blood flow resistance (Glazier, 2022). Numerous factors contribute to vascular constriction, as illustrated in Figure 1. These factors include an elevation in sympathetic nervous system activity, which triggers vasoconstriction, and endothelin, a chemical substance responsible for vasocontraction

Treatment Plan

The patient has been on several drugs in an attempt to lower her blood pressure to normal levels. She has been cyclobenzaprine 5 mg nocte PRN, carvedilol 25 mg, amlodipine 5 mg 24 hourly, furosemide 40 mg, and atorvastatin 80 mg nocte. Nursing management can be used in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. According to Fu et al. (2020), the nurse can incorporate nursing interventions for stress management, such as breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and meditation. The other nursing interventions that can aid in managing the condition are patient education on medication adherence, frequent follow-up, and lifestyle changes. Grillo et al. (2019) suggest that an elevated sodium intake can increase water retention, thus altering blood pressure levels. Therefore, the patient should monitor her fluid intake to prevent overload.

Worsening Condition

Vascular and organ damage may be caused by the adverse impacts of high blood pressure on the arterial walls. Both severity and period of untreated high blood pressure lead to progressively more significant degree of harm. Uncontrolled Blood Pressure may lead to heart attack (Siddiqui et al., 2019). High blood pressure can cause arteries to develop a thick layer, making them more rigid or stiffer. Untreated hypertension can deteriorate, leading to aneurysms, which are very likely fatal.

Heart failure is one complication of high blood pressure. This may be attributed to a situation where the heart has to work extra hard to ensure that enough blood reaches vital organs in the body. The wall of the pumping chamber increases in thickness due to the strain. In turn, the heart fails to supply adequate blood as needed for the body, leading to heart failure (Siddiqui et al., 2019). In addition, one might develop kidney failure secondary to the rise in blood pressure. This is because hypertension may make the arteries of the kidney loose (De Bhailis et al., 2022). Moreover, the condition may deteriorate and disturb regular optical operation. Hypertension can result in thickening, constriction, and tearing of arteries in the eye, causing blindness.

Moreover, worse outcomes for the patient can involve changes in memory and understanding. Unmanaged blood pressure can affect an individual’s ability to remember and think. Moreover, narrowed arteries can limit blood flow to the brain, resulting in vascular dementia (Siddiqui et al., 2019). This can affect an individual’s judgment and thinking, resulting in difficulty speaking, expressing thoughts, and writing. This might affect the client’s daily functioning, resulting in individual and social impairments.

Improved Conditions

When the client’s blood pressure stabilizes, there will be an improvement in the patient’s life. For instance, the patient would have reduced fear related to the risk of cardiovascular events. Hypertension is a key risk factor for the development of cardiovascular events such as stroke, heart attack, and heart failure, according to Fuchs and Whelton (2020). Furthermore, improving the condition would safeguard the kidneys from potential injury. De Bhailis et al. (2022) assert that when kidneys are exposed to high blood pressure, they are likely to be damaged. The patient will likely save costs that are likely to be incurred in purchasing medications to manage the disease. Individuals free from the ailment are likely to have a reduced risk of complications such as dementia and vision loss.

Conclusion

Wilhelmina presented to the hospital with hypertension, which she has been managing through medications. Her condition is likely to be caused by diverse factors, such as an impairment in renal pressure natriuresis, the RAAS system, and an increase in TPR. The patient can have improved outcomes, such as reduced medication cost and limited complications, through nursing interventions such as education on diet and stress management. If her health worsens, she may develop organ limitations, a heart attack, or possibly dementia.

References

Adua, E. (2023). Decoding the mechanism of hypertension through multiomics profiling. Journal of Human Hypertension, 37(4), 253-264. Web.

Chobufo, M. D., Gayam, V., Soluny, J., Rahman, E. U., Enoru, S., Foryoung, J. B., Agbor, V. N., Dufresne, A., & Nfor, T. (2020). Prevalence and control rates of hypertension in the USA: 2017–2018. International Journal of Cardiology Hypertension, 6. Web.

De Bhailis, Á. M., & Kalra, P. A. (2022). Hypertension and the kidneys. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 83(5), 1–11. Web.

Flack, J. M., & Adekola, B. (2020). Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 30(3), 160–164. Web.

Fu, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, L., Zhou, L., Li, D., Quan, H., Zhu, L., Hu, F., Li, X., Meng, S., Yan, R., Zhao, S., Onwuka, J. U., Yang, B., Sun, D., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Nonpharmacologic interventions for reducing blood pressure in adults with prehypertension to established hypertension. Journal of the American Heart Association: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease, 9(19). Web.

Fuchs, F. D., & Whelton, P. K. (2020). High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension, 75(2), 285–292. Web.

Glazier J. J. (2022). Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of hypertension in the elderly. The International Journal of Angiology: Official Publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc, 31(4), 222–228. Web.

Grillo, A., Salvi, L., Coruzzi, P., Salvi, P., & Parati, G. (2019). Sodium intake and hypertension. Nutrients, 11(9), 1970. Web.

Siddiqui, M. A., Mittal, P. K., Little, B. P., Miller, F. H., Akduman, E. I., Ali, K., Sartaj, S., & Moreno, C. C. (2019). Secondary hypertension and complications: diagnosis and role of imaging. Radiographics: A review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc, 39(4), 1036–1055. Web.