Analysis of the Children’s Market

Children’s market can be defined as a sector of market responsible for providing children with essentials such as food and clothes to satisfy their basic needs and extras for their entertainment. Childhood is traditionally defined as the period of life between birth and puberty at the age of 10-11 for girls and 11-12 for boys.

Children who are financially dependent upon their parents or carers can influence the adults’ decisions and expenses by expressing their personal opinions. Therefore, marketing of children’s goods should address both adults who are the main decision-makers and children who can influence the decisions of adults (Fennis & Stroebe, 2010, pp.42-45).

Taking into account the fact that children are recognized as a vulnerable audience, it can be stated that marketing strategies which should be used for this young audience are rather controversial and associated with a number of ethical concerns.

After the post-World War II decade of baby boom which coincided with the advent of television, children have become consumers and the target audience of marketers. Realizing that children spend a substantial amount of their time on watching TV, marketers realized that they can reach kids directly to influence their consumer choices instead of focusing on their parents.

Under the influence of television advertising, children have become conscious consumers making their choices and giving their preference to toys and brands advertised on TV. Coupled with the phenomenon of the so-called KGOY (Kids Grow Old Young), kids aged 2-11 have become an important target audience for marketers.

There is evidence that even toddlers at the age of 3 and under can obtain substantial brand awareness and can influence decisions of their parents. As compared to preschoolers a decade ago, kids at the age between 3 and 5 today behave more like 8 or 9-year-olds used to behave in terms of brand awareness.

Analyzing this social shift, McNeal (1992, p. 29) admitted that children’s market has greater potential than any other age group. McNeal (1992, p. 29) distinguished between three main segments of children’s market, including those of primary, influence and future markets.

The amount of children’s personal money has significantly grown and kids are free to spend their money on products of preferred brands. According to McNeal (1992, p. 29), the income of children at the age of 4-12 can be estimated at approximately $27 billion.

Additionally, children can influence their parents’ buying decisions through their hints or even demands. Moreover, present-day kids will make most of their purchases in the future though their brand awareness is being shaped at this tender age. Summing up these three important segments, children form one of the greatest marketing potentials as compared to the rest of demographic groups.

Along with the global tendencies of children growing young, kids’ advanced brand awareness and great potential of the world children’s markets, there are a number of cultural differences which are observed in this segment throughout the world.

By applying Hofstede’s 5 cultural dimensions to the children’s markets in the UK, US and Eastern Europe, a number of significant differences can be indicated. The first dimension of power distance is much higher in Eastern Europe in general and post-Soviet countries in particular as compared to Western countries.

Because of the specifics of the historical development, organization and functioning of the states, less powerful members of society in Eastern Europe emphasize that power is distributed unequally. The second dimension defining the extent of uncertainty avoidance is significantly higher in Eastern Europe due to the poor results of the state’s efforts to control the uncontrollable.

Therefore, members of Eastern European societies would feel uncomfortable under unknown and surprising circumstances and try to avoid such situations. As to the third dimension of individualism versus collectivism, it can be stated that because of peculiarities of historical past, Eastern European countries tend to be more collectivist and their citizens are more involved into different social groups, whereas the Western communities, including the UK and US are more individualist.

The fourth dimension focuses on masculinity versus femininity of national cultures which refers to the distinction of emotional gender roles. In general, according to the classification provided by Hofstede (2003, p. 147), culture of Russia and other Eastern European countries are collectivist and feminine, and culture of UK and USA is individualist and masculine.

The only overlap in culture of Eastern Europe, UK and US is the fifth dimension, namely relatively short-term orientation, due to which the members of the communities mainly neglect the guidance from their past which could be helpful for improving their results. These important characteristics need to be taken into account for selecting the most appropriate marketing strategies for children’s markets of different regions.

Standardization Versus Adaptation of the Product

Regarding the dispute concerning standardization of products versus their adaptation to the specifics of particular markets, the extent of cultural similarities and differences in particular countries need to be taken into account for making an appropriate decision.

There are a number of similarities in the implementation of children’s rights in the United States, the United Kingdom and Russia defined in the International Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC). Therefore, these countries have similarities in the legislation concerning what children can read and the content of materials distributed among children.

Regardless of certain flaws in the mechanism of implementing the Convention in Russia, the Russian legislation does not hinder the import and export of printed materials. The domestic markets of these countries are highly integrated and encompass many developing structures in the market which attracts many people (Hollensen, 2008, pp.156-158).

Therefore, there are similar tendencies in controlling the distribution and content of children’s goods in the UK, US and Eastern Europe even though the level of success of legislation efforts in different countries can vary (Stuart, 2009, pp.23-34; Harrell, 2001, pp.116-118).

Assuming that the content of children’s magazine is identical in its UK and US versions with only minor changes focusing on the language means, it can be stated that the strategy of standardization is adopted by the magazine. The largest part of the magazine’s content is educational and most entertaining parts focus on certain educational objectives (Solomon, 2009, p. 52).

Analyzing the significant cultural differences between US, UK and Russia which can be clearly seen on the example of Hofstede’s five dimensions, it can be stated that mere translation of the magazine’s content would be insufficient for reaching the audience of Russian kids.

Due to the differences in adopted values of the discussed countries in most dimensions, it can be stated that the adaptation strategy would be preferable for the launch of children’s magazine in Russia (Solomon, 2006).

Taking into account the fact that children’s magazines are a culturally bound products because its content depends upon cultural peculiarities and traditions regarding educational strategies, it can be stated that the content of the UK/US magazine will have to be adapted to the needs of the target audience (Lake, 2009, pp.91-93).

For instance, the editors will need to substitute some heroes of the stories and substitute them with heroes familiar and understandable for Russian kids. Moreover, the emphasis of the magazine which is put on educational materials will need to be shifted to more entertaining content.

There is evidence that the tendency of adapting or even plagiarizing the values of Western cultures has been observed in Eastern European cultures (Dymkovets, 2009). In other words, the Russian media borrows a lot of ideas from Western culture, including the ideas for TV shows and fairy tales.

The US cartoons are extremely popular with Russian children, and their heroes are recognizable.

The Walt Disney Company is going to launch its channel in cooperation with Russian UTH television channel early next year. Even though the results of this cooperation are yet unknown, this decision clearly demonstrates the popularity of Disney products among Russian kids (Invest in Russia, 2011). Disney is also a title of one of the most popular children’s magazines in Russia.

Regarding the online version of the magazine, it can be stated that due to the limited broadband penetration, the online magazine as a method of distribution used in the UK and US is inappropriate for Russia (Hughes, & Marshall, 2008; Pride, 2005, pp.79-82).

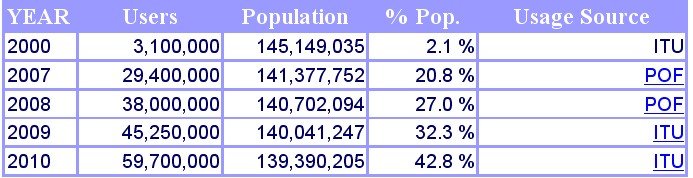

According to the data of the Internet World Stats (2010), there are not more than 59, 700, 000 Internet users as compared to 139, 390, 000 as the estimated population of the country. Therefore, regardless of the noticeable progress in the sphere of Internet access in Russian population, the broadband penetration still remains limited and this limitation can become a significant hindrance for the launch of an online version of children’s magazine in Russia (Solomon, 2009, pp.21-26).

In general, it can be concluded that printed version is a preferable method of distribution and adaptation is a more appropriate strategy for the launch of a children’s magazine in Russia.

Analysis of Russia

Regardless of the attempts of the Russian enterprises to attract foreign investors and substantial returns of such investments in particular spheres, the environment of this Eastern European country is unfavourable for the launch of children’s magazines.

The main reasons for this decision include cultural differences which would require substantial costs for translation and adaptation of the magazine’s content, the current demographic problems in the country and insufficient levels of political stability and economic growth.

Due to the disparity in cultural values, large power distance, high uncertainty avoidance, collectivist feminine culture, the content of the UK/US magazine will require substantial changes to adapt it to the needs of the Russian audience (Wänke, 2009, p. 65).

Moreover, taking into account the fact that children’s magazines is a highly culture-bound products, it can be stated that certain fragments from the UK/US version will need to be omitted or substituted. Additionally, due to the limitations of the broadband penetration, an online version of the magazine extremely popular with UK/US audiences can be ineffective for reaching Russian kids.

Another factor which should be taken into account is the competition of the local magazines, including those of the world’s oldest magazine Murzilka published since 1924 and others including Veselye Kartinki, Misha, Nyanya, Eralash and others.

These editions are based on the unique colouring of Russian culture which explains their popularity among young readers (Doole & Lowe, 2005). Regardless of the popularity of Disney magazine and the intentions of Walt Disney Company to launch its channel on Russian television, the launch of the children’s magazine in Russia will cause a number of problems which reduce its potential profitability and attractiveness.

Along with the cultural disparity, the demographic problems and economic situation need to be taken into consideration to evaluate the favorability of the Russian children’s market and the environmental risks (Pride & Ferrell, 2010, pp.34-40).

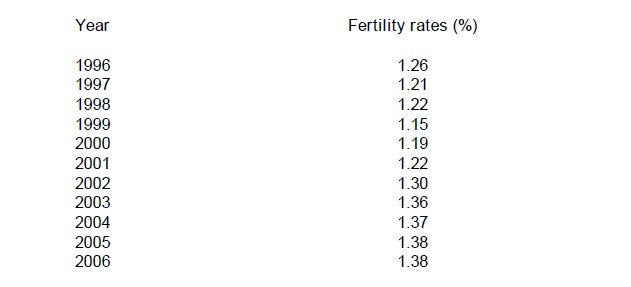

According to Datamonitor (2007), the current fertility rates in Russia are higher if compared to the rates of 1990s. However, the current rate of 1.38% is rather low and this can have a negative impact upon the children’s market under analysis.

Additionally, the rates political stability and economic growth in the country are insufficient and coupled with bureaucratic delays poor communications and local managerial skills create unfavourable environment for the launch of a foreign children’s magazine.

Taking into account the disparity in cultures, demographic problems and the lack of technological and economic development of Russia, it is advisable to consider the potential of launching the magazine in Poland.

The culture of Poland is closer to that of the UK and US. For instance, as well as the US and UK, the culture of Poland is individualist and masculine, the power distance is also smaller than the Russian one. Therefore, fewer changes will be necessary if adaptation of the magazine’s content will be necessary.

Additionally, the economy of Poland is on the rise. However, the competition of the local editions and business environment risks deserve serious consideration before the launch of the magazine in Poland.

References

Datamonitor, 2007. Russia country profile. [online] Web.

Doole, I. & Lowe R., 2005. Strategic marketing decisions in global markets. New York: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Doole, I. & Lowe R., 2008. International marketing strategy: Analysis, development and implementation. New York: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Dymkovets, A. 2009. Cultural clones. Russian Life [online] Web.

Fennis, B. M. & Stroebe W., 2010. The psychology of advertising. New York: Routledge,

Harrell, G. D., 2001.Marketing: Connecting with customers. New York: Prentice Hall

Hofstede, G. 2003. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions

Hollensen, S., 2008. Global marketing. New York: Financial Times Prentice Hall,

Hughes, A., & Marshall, L., 2008. Marketing: Real people real choices. Canberra: Pearson Education Australia

Internet World Stats: Usage and Population Statistics, 2010. Russia Internet usage and marketing report. [online] Available from: https://www.internetworldstats.com/euro/ru.htm

Invest in Russia, 2011. Walt Disney and UTH Russia to launch an ad-supported free-to-air Disney Channel in Russia early next year. [online] Available from: http://investinrussia.biz/news/walt-disney-and-uth-russia-launch-ad-supported-free-air-disney-channel-russia-early-next-year-56b8.

Lake, L., 2009. Consumer Behavior for Dummies. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

McNeal, J. 1992. The kids market: Myths and realities. Ithaka: Paramount Market Publishing.

Pride, W. M., 2005. Marketing. New York: Houghton Mifflin College Div,

Pride, W. M., & Ferrell O. C. 2010. Foundations of marketing. New York: Cengage Learning,

Solomon M. R., 2006. Consumer behaviour. New York: Prentice Hall PTR,

Solomon M. R., 2009. Marketing: Real people, real decisions. New York: Prentice Hall PTR,

Stuart, S. M., 2009, Marketing: Real people, real choices. New York: Pearson College Div.

Wänke, M., 2009. Social psychology of consumer behaviour. New York: Psychology Press.