Problem Statement

Individuals at risk of poor health and healthcare disparities are normally regarded as being vulnerable. For homeless persons and other socially marginalized populations, an effective healthcare system is always not within their reach. Moreover, other social determinants of health, such as income, housing, and social support are often not present. No clear approach to healthcare delivery for homeless persons and other vulnerable people has been defined. Vulnerability, which is likelihood to harm, emanates from an interaction among various factors, including an individual, society, and prevailing life challenges encountered.

Notably, vulnerable people experience extremely high rates of acute and chronic behavioral health disorders and physical conditions and injuries than the general population. Usually, these conditions remain unmet medical needs. Further, competing interests, such as housing and food, implies that vulnerable people may not always prioritize health needs. Most of them are uninsured and often seek care in emergency departments (EDs) when unmanaged symptoms lead to hospitalization.

Project Description and Overall Goal(s)

The practicum, “Improving the Overall Health of Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio”, seeks to improve health of homeless individuals. The program will target 40 homeless residents aged between 18 and 75. The overall objective of the project will be to ensure that those who reside in the shelter are encouraged to take care of their own health through access to the necessary knowledge.

This project will be implemented in Hope House Mission, a faith-based shelter for the homeless. Its mission is to provide a wide of range of programs and services designed to achieve long-term, sustainable life transformation for homeless children, men, and women. Homeless persons usually have perceived unmet health needs, and they use high-levels of healthcare, usually in costly emergency departments or acute care settings (O’Toole, Johnson, Aiello, Kane, & Pape, 2016). Thus, the practicum, which is a holistic in approach to public health, will ensure that Hope House Mission and homeless persons have enhanced capacity to address healthcare needs they experience.

Rationale

The practicum is expected to run for about 24 weeks (six months), and will be performed via PowerPoint presentation and following with discussion. Since the facility lacks the equipment to accommodate for the laptops or projectors, I plan on giving each individual a print out of the desired topic being addressed. Having identified the health needs that continue to affect the residents of Hope House, the project leader developed several topics that will be used to improve the overall health of people at the facility.

These topics will aim not only to empower the residents with the knowledge on how to deal with common health issues, but also to underscore the importance of self-worth and self-esteem in managing challenging conditions. Some of the topics that will be addressed in this project are medication management, diabetes and hepatitis C management, self-neglect, oral health management, and vision management. Classes and group discussions will be held on a weekly basis with the residents of the Hope House, who will be encouraged to attend to ensure they gain useful knowledge on how they can deal with common health issues.

Objectives

The objectives of this practicum address multiple areas of public health improvement among homeless persons in Hope House. The objectives include:

- Increase awareness in homeless people about the significance of overall health and well-being

- Increase acceptance and usability of effective preventive interventions and treatments in homeless persons at Hope House

- Promote educational interventions to lessen healthcare problems in homeless shelters

- Enhance the capacity of homeless shelter programs to offer preventive health services to homeless persons at homeless shelters

These objectives are designed in line with the overall goal of the practicum. Thus, at the end of the practicum, noticeable changes in knowledge, awareness, and practices would be expected in homeless persons at Hope House.

Review

Homeless persons are considered vulnerable, and vulnerability, as previously noted, emanates from multiple sources (Grabovschi, Loignon, & Fortin, 2013; Culo, 2011). For homeless persons, the rate of healthcare challenges are higher compared to the general population (Lin, Bharel, Zhang, O’Connell, & Clark, 2015). For medication management, it is shown that vulnerable people are at greater risks because of limited abilities to manage a complicated medication regimen based on multiple conditions they may experience. Non-adherence to medication, therefore, is a primary contributing factor for poor healthcare outcomes in vulnerable people. As such, interventions, such as education, that help such individuals to manage their medication could assist in avoiding needless, costly emergency department visits, admission, and hospitalization, as well as help in improving quality of life (Knowlton, Nguyen, Robinson, Harrell, & Mitchell, 2015).

Diabetes and hepatitis C virus are two health problems considered as chronic. Studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between diabetes and hepatitis C virus (Ba-Essa, Mobarak, & Al-Daghri, 2016). Notably, patients who share personal items, occupational exposure to blood or its related products, tattooing items, increased transaminases and risk practices were most likely to have both conditions leading to frequencies of hospital admission (Ba-Essa et al., 2016). These results underscore the need for educational intervention for vulnerable persons.

From a broader perspective, self-neglect is a growing condition that is poorly understood social and medical challenge. Self-neglect is a multifactorial behavioral issue that accounts for an individual’s inability or a rejection to attend to own health, personal hygiene, and personal and environmental needs (Culo, 2011).

Self-neglect is the chief reason for “referral to adult protection services” (Culo, 2011, p. 421). In this case, unsafe behaviors expose individuals to self-endangerment, which is an isolated risk factor for death and institutionalization. Vulnerable persons, especially older adults, who demonstrate self-neglect tendencies, usually live in situations of greater isolation, squalor, and foulness. Such individuals may refuse any help because they do not see anything amiss in their conditions.

However, they present safety hazard and health risks to self and others. It is imperative to understand that such cases are controversial and, thus, care providers often argue whether the condition is social or medical, especially when mental conditions are absent (Culo, 2011). In the end, the issue of self-neglect comes to semantics. Nevertheless, individuals who neglect themselves are incapable and sick, and care providers should not ignore them (Culo, 2011). This explains why the practicum will adopt a holistic approach to address overall health and well-being of homeless persons.

Not much is known about the ocular condition of homeless persons (Noel et al., 2015). Visual acuity is significantly associated with reduced overall well-being. Thus, it is a critical educational program for homeless shelters, which host majorities with such complications. The training program will explore factors related to visual impairment and demonstrate the relevance of constant visual screening programs and treatment for homeless persons, especially where free eye clinics are found to help address this unmet health need.

Poor oral health based on all measurement indicators, such as decayed teeth, missing teeth, and oral pain, have been found among homeless persons (Costa et al., 2012). The educational program will cover causes, symptoms, diets, and offer a list of physicians who accept Medicaid and Medicare.

Competencies

This project lies squarely on the public health domain as it aims to protect the safety and improve health of the homeless members of the Hope House community through education. Rather than seeking to provide diagnostic interventions for the health problems affecting the homeless, the project aims to create awareness and empower the homeless on how to manage these issues through education. Additionally, this project is in the public health realm because the feedback received from the intervention could be employed to develop policies and processes in order to ensure the safety and health improvement of the homeless members of the community. Overall, the project’s focus on improving the overall health of Hope House residents makes it a public health issue as the main goal of public health interventions is to safeguard improve health of different community members through education, policy making, and research on disease and injury prevention.

Methods

A holistic approach to public health was used to ensure that the project helps develop all aspects of peoples’ lives that are critical to improving the overall health of the targeted population. The approach was based on the realization that most residents of Hope House face different health challenges and, thus, a holistic perspective was needed to ensure that the project would have an impact on physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual needs of the residents. The justification for using this perspective was due to difficulties to improve the overall health and well-being of the targeted population without adopting such a perspective. The integrated educational package ensured a holistic approach to improve health and well-being of homeless persons while addressing care and underlying health challenges leading to emergency department use (O’Toole et al., 2016).

This practicum containing educational programs prepared by the presenter was presented to homeless persons through face-to-face using oral PowerPoint presentation and brochures. I printed out the copies for each individual participants. The educational interventions happened in a private room, which had a sitting arrangement for about 50 people. These learning materials were kept in a binder to be used as toolkits and references to ensure the continuity of the project even in the absence of the main implementer and for educating new residents. The toolkits contained information and resources to assist the homeless people residing in the shelter in improving their overall health on different levels – physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual.

The project targeted between 35 and 45 homeless individuals at Hope House (note that it was not difficult to find all homeless people at the shelter on a specific day). One general approach to assess learning in the educational package was to administer a pre-test and a post-test examination (Boston University, 2013). The pre-test was administered at the start of the instruction to assess pre-existing knowledge of the content program, including medication management, diabetes and hepatitis C management, self-neglect, oral health management, and vision management. Dr. Jaana Gold (my advisor) and Mrs. Lisa Field (my preceptor) approved the questionnaire before I gave to the residents. Later on at the end of every instruction program involving oral presentations and group discussions, a post-test assessment was administered in an effort to show measurable achievements in homeless persons’ knowledge. The entire practicum lasted 24 weeks (see the table below).

Impact evaluation was used at the end of the interventional educational program to determine the degree to which the practicum met its main goal of knowledge acquisition in homeless persons at Hope House. It was an important instrument to improve the quality of program and improve the outcomes. In this case, pre-test and post-test assignments was used for the practicum evaluation.

Collected data were analyzed using frequencies and percentage to determine changes in knowledge following implementation of the project for homeless persons. Changes in percentage prior to and following the practicum determined potential new knowledge acquired.

Sufficient resources, such as time, funds, instructional materials, and others, were provided to facilitate the implementation of this practicum. The overall interventional educational practicum addressed the following topics: medication management, diabetes and hepatitis C management, self-neglect, oral health management, and vision management within 24 weeks. The topics were divided into different weeks to facilitate the implementation of the practicum through oral PowerPoint presentation, group discussions, pre-tests, post-tests, and brochures to reinforce learning.

Data Analysis

Data analysis involved determining the difference between pre-test scores and post-test scores of homeless men who took part in the integrated educational program to improve their oval health. Analysis was done by examining the change in scores of individual participants to determine if there were any indications of a gain because of education provided. For each participant who took part in both pre-test and post-test, a variation in score (the value of post-test score less the value of pre-test score) for the entire topics covered during the program. This is generally the appropriate way to interpret the impacts of a training program in a given pre-test post-test test, since it allows the researcher to determine the extent of the difference in scores. Scores are displayed in graphic formats and tables for clarity.

Individual improvements of a given point show enhanced thinking (diminished weakness to basic thinking mistakes) and improvements of many points are great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the training program. These increases in the whole score demonstrate significant changes in learners. The variation in percentile score depends on where the learner’s score is found in the curve. It is imperative to recognize that scores of an individual may drop if the individual is not sure or lacks consistency when they select the best responses for the tasks. However, a drop in scores of many points is normally a characteristic of poor effort at post-test without some other influencing factors, for example, cognitive damage, exhaustion, or testing conditions. Data were analyzed using Excel.

Results

It is important to recognize that the number of participants in who participated in this program in different educational topics were not the same because of homelessness status of participants. For each educational topic, the participants ranged between 35 and 45 (hence, n = 35 – 45). The program was delivered over the course of five months. Only homeless men sheltered at Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio and aged between 18 years old and 75 years old took part in this educational program.

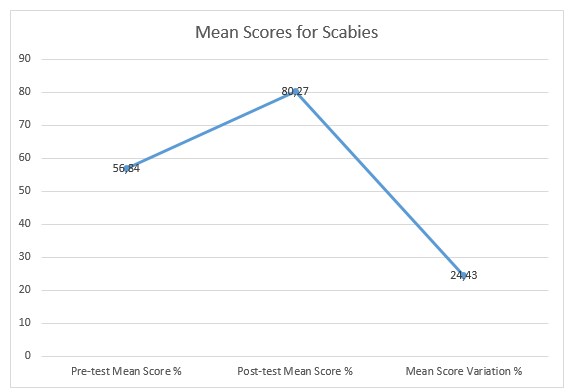

For educational program on scabies, the number of participants was 45. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was also administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 56.84, and the mean score percentage for post-test was 80.27. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 23.43, indicating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

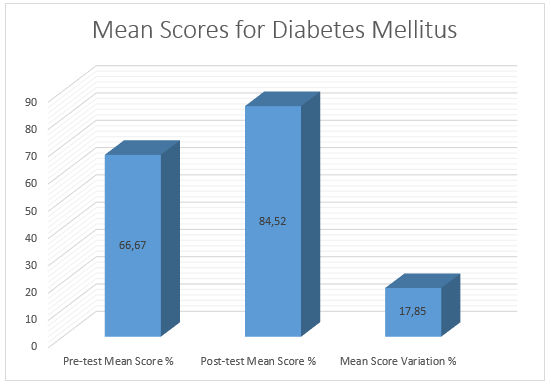

Participants were also tested on diabetes mellitus after the educational program. There were 42 learners who took both pre-test and post-test tests. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 66.67 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 84.52. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 17.85, indicating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

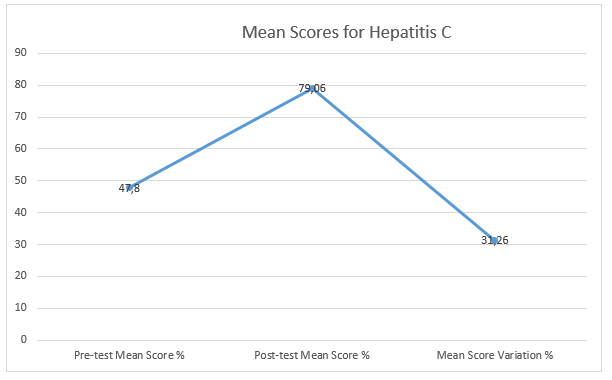

Learners’ change in knowledge was also tested following educational program on hepatitis C. This class had 35 participants who took both pre-test and post-test tests. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 47.8 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 79.06. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 31.26, demonstrating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

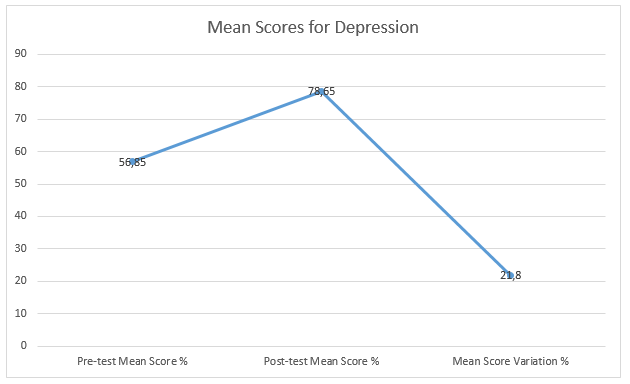

Learners’ change in knowledge was also tested following educational program on depression. This class had 40 participants who took both pre-test and post-test tests. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 56.85 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 78.65. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 21.8, demonstrating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

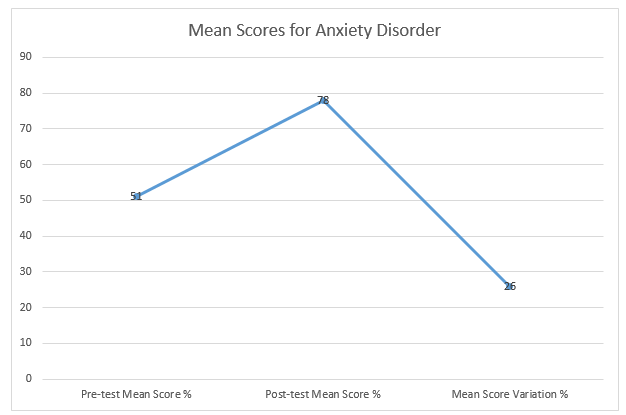

Participants’ change in knowledge was also tested following educational program on anxiety disorder. This class had 45 participants who took both pre-test and post-test tests. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 51 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 78. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 26, demonstrating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

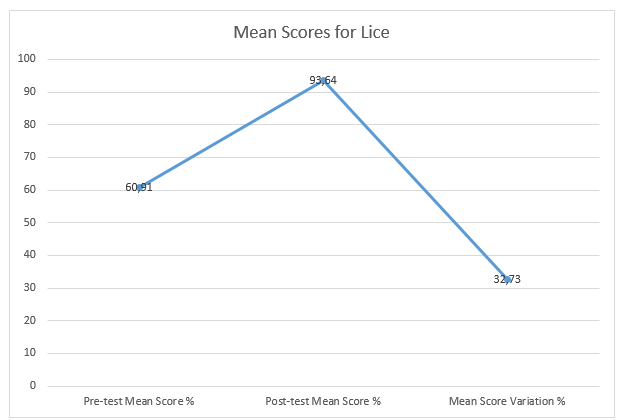

Participants’ change in knowledge was also tested following educational program on lice. This class had 45 participants who took both pre-test and post-test tests. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 60.91 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 93.64 Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 32.73, demonstrating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

For educational program on nutrition, the number of participants was 45. Pre-test was administered before the start of the educational program and post-test was also administered at the end of the educational program. The mean score percentage for pre-test was 48.04 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 77.02. Tests administered in the pre-test assessment were the same tests used in the post-test assessment. The mean score percentage difference between pre-test and post-test was 28.98, indicating an improvement of many points, which was a great confirmation that learners actually benefited incredibly from the educational program.

Summary of the Results

The above findings demonstrated that participants who took part in the educational program to improve overall health of homeless male at Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio did exceptionally well. For educational program on scabies, the mean score percentage for pre-test was 56.84, and the mean score percentage for post-test was 80.27, indicating a percentage gain of 23.43. Test scores for diabetes mellitus showed the mean score percentage for pre-test as 66.67 and the mean score percentage for post-test as 84.52, showing a percentage gain of 17.85. Additionally, for educational program on hepatitis C, the mean score percentage for pre-test was 47.8 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 79.06, which showed a percentage gain of 31.26.

Assessment results for showed that the mean score percentage for pre-test was 56.85 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 78.65, reflecting a knowledge gain of 21.8%. For anxiety disorder, the mean score percentage for pre-test was 51 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 78, depicting an increment in knowledge by 26 percent. The results of the assessment for lice showed that the mean score percentage for pre-test was 60.91 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 93.64, reflecting a change of 32.73 percent. Finally, The mean score percentage for pre-test was 48.04 and the mean score percentage for post-test was 77.02, showing a gain of 28.98 percent in the case of nutrition.

The participants who received this educational program gave overwhelming responses and enjoyed the educational materials left for references and future programs. They were delighted to have these classes and looked forward for more.

Discussion

This project focused on improving the overall health of Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio. Its mission was to provide wide-ranging programs and services designed to achieve long-term, sustainable life transformation for homeless men aged between 18 years old and 75 years old. The overall objective of the project was to ensure that men who reside in the shelter were encouraged to take care of their own health through access to the necessary knowledge. A holistic approach to public health was adopted for this educational program.

It should be clear that limited literature is available to provide empirical evidence for health educational programs for homeless individuals. In fact, a more comprehensive work was done in 1994 by May and Evans, and they too observed little report in research specifically for health education targeting homeless persons. Instead, current literature tends to focus on health promotion, which is a wide scope approach for interventions for health education for homeless populations. Nonetheless, the past research determined that healthcare educational programs for the homeless persons in shelters were often delivered by volunteer instructors, such as nurses, who offered lessons on health promotion, disease prevention, and self-care (May & Evans, 1994).

In light of the review of assessment results for a year and a half, it was found that 50 volunteer educators, the greater part of whom were nurses, provided 49 healthcare topics in 176 classes (May & Evans, 1994). Learners showed that the classes were useful, and they expressed their desires for future studies. This research conducted in 2017 still reflects findings established more than two decades ago by May and Evans. It confirms that health educational programs are hardly available to homeless individuals in their shelters, although they always express their desire to have search services.

Homeless is a complex, far-reaching issue in the United States (Coles, Themessl-Huber, & Freeman, 2012). Current health promotion underscores the ideas of lifestyle change, risks, and preventive health behavior, as well as the more extensive societal issues of the environment, public policy, and cultural influences. Therefore, the focus has shifted to a more planned way to deal with health promotion for individuals who are socially excluded, stressing behavioral change by focused interventions at the level of community settings, including homeless shelters.

Research concentrated on homelessness and related health challenges (Costa et al., 2012; Grabovschi, Loignon, & Fortin, 2013; Knowlton et al., 2015), and findings demonstrate the need for urgent action, yet little consideration has been given to the health promotion needs of homeless persons, and there is no clear proof of evidence-based outcomes following interventions. One issue for health promotion is to create and deliver suitable educational activities to a heterogeneous populace that is not generally simple to classify but rather has an extensive variety of health needs. As such, this study settled on a holistic approach to address multiple health concerns of homeless men.

For instance, the healthcare needs of a young fellow without a shelter vary widely from those of an old homeless man with other conditions related to advance age. To be destitute goes beyond a lack of a shelter alone, and it includes other health-related issues among other challenges. Homelessness has as much to do with social exclusion as with housing, and requires a wide range of health promotion methodologies.

Due to lack of earlier interventions and exclusion (Campbell, O’Neill, Gibson, & Thurston, 2015), homeless persons are more probable than other populations to present with a severe illness and regularly utilize accident and emergency units for their healthcare needs. As a result, they are frequently missed by essential care health promotion initiatives.

Usually, healthcare services focused on homeless persons incorporate visiting care providers, community workers, health advocates, and occasional specialists, for example, general practitioners and community nurses, who have given intervention in homeless facilities and day centers (Jego et al., 2016). This study supports a more sustained implementation of educational programs for homeless persons as constituents of health promotion programs. Given these results, health promotion ought to be created with regard to how homeless persons look for care services. As such, this may include significant adjustment of, or specifically a move away from, conventional cases of care delivery, for example, in primary care setting situated in main hospitals.

Many intervention programs aimed for homeless persons have concentrated on illness prevention and are to a great extent not published (Jahan, 2012). These interventions incorporate immunization programs, mobile screening facilities, and the dissemination of condoms, but educational programs are not generally common because of resources (Ba-Essa et al., 2016; Knowlton et al., 2015). Intervention programs also tend to focus on youthful homeless living in the streets, in hostels, or other forms of accommodation facilities. Groups, for example, elderly individuals and families living in temporary settlement have largely been disregarded.

Even in this study, the focus was only on male, leaving out female homeless persons irrespective of their needs. Homeless care services are frequently engaged in emergency services provision and, thus, the long-term care of homeless persons is not generally a priority. Undoubtedly, health may not be a need for homeless persons themselves. Rather, basic survival needs, for example, food, water, and shelter may occupy their thoughts more than the likelihood of diseases. Hence, one valuable intervention may just be to inform such an individual where the closest shelter offering food and drink is. Thus, health promotion ought to likewise give useful help, for example, food, drink, and clothing. In the meantime, information can also be given about how to avoid some health risks and improve general hygiene.

The main objective of the homeless health educational program is usually to offer health information to homeless people and families in an unmistakable, precise, socially acceptable way to advance understanding, involvement, motivation, empowerment, and constructive health behavior change. This aim is successfully realized by applying different techniques drawn from the areas of health education and social or community work.

Engaging homeless persons is extremely important to service delivery because offering specific health information and supportive solution can only take place when individuals have expressed their concerns openly to care providers. Once educational programs have been provided, it is imperative to explore the recommendations and implement them. For instance, shelter providers should now strive to improve the provision of health information by organizing many formal educational and interventional classes and individually focused sessions on health subjects or topics important to needs of specific groups.

Health instructors give training and support around a wide scope of themes, for example, hypertension, nutrition, asthma, diabetes, hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, condom use, pregnancy, tuberculosis, physical activity, cancer, tumor, smoking, alcohol abuse and other substance abuse, oral health, and stress management, to give some examples. This demand for health educational programs demonstrates a complex system that requires a holistic approach.

This study was based on the formal needs of homeless persons at Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio. Irrespective of the lack of published findings, there are cases of specific issues that healthcare promoters consider great practice. These strategies account for national campaigns designed to meet local health needs, health fairs and other group based health promotion events, and outreach programs specifically designed for homeless persons. Strategies relying on peer interventions, concentrating on counselling and rapport building have also been effective. Many experts have now established services to cater for health needs of homeless individuals.

Training materials, especially those concentrating on chronic disease, such as HIV and AIDS information tend to target young homeless people while other health information on diabetes, heart conditions, obesity and others are have been targeted for older homeless persons (Culo, 2011; O’Toole et al., 2016). This demonstrates attempts to reach specific segments of homeless individuals. Health promoters have additionally focused on the significance of practical solutions.

As such, instructing homeless individuals about dental care might be inconsequential simply because they a toothbrush and toothpaste, and care for personal hygiene may not generally be practical for individuals sleeping in the streets. Thus, straightforward, practical help may occasionally be the most suitable type of health promotion. Health promotion efforts, therefore, should be accompanied by some quick and practical solutions. For instance, homeless alcohol and drug abusers might be more amiable to general health promotion activities once they are some forms therapies.

It is also important to recognize that health promotion efforts targeting homeless individuals may not record the best success rates (Jahan, 2012). This implies that multiple barriers are faced before homeless individuals can receive the intended health promotion initiatives. These barriers have been linked to multiple issues. First, health educational initiatives or educators are often isolated. As such, little collaboration or coordination is noted between stakeholders. In fact, it is recommended that any interventions targeting homeless individuals should be an integrated, multidisciplinary approach (Maness & Khan, 2014).

Second, public health departments have largely ignored health promotion and education for homeless persons. Third, some health promotion materials are written in technical languages, which usually need high levels of literacy or specialized knowledge. Hence, homeless persons feel excluded by such materials. Finally, while homeless persons may eagerly seek care, low self-esteem and diminished expectations often inhibit them from involving health promotion initiatives.

Some challenges are more complex. Numerous organizations do not have the capacity to implement health promotion without support. An essential factor is to gather the right resources and workforce, and design a framework for health promotion (Jahan, 2012). Health promotion also faces vested interests of various stakeholders. Powerful entities, such as businesses, are most likely to influence health promotional outcomes, for instance.

There is an increasing acknowledgment of part of ethics and, thus, stakeholders are expected to emphasize the practical reasons and benefits for health promotion. Educational programs are the best interventions engage homeless persons to determine what they value and how they can embrace practical approaches to reduce health risks and management existing conditions. To accomplish this goal, particular interventions to local circumstances are required as opposed to treating all groups similarly. Another issue is to develop a long-term rapport with marginalized individuals, such as homeless persons.

As poverty and inequality escalate in society, homeless persons and other disadvantaged groups may fail to appreciate any messages associated with health promotion. It will require some efforts, time to stakeholders offering related services, and find the right homeless persons. More importantly, this study revealed that homeless persons in different setting require different approaches. As such, the study strives to enhance access to health care for marginalized, underserved persons in society, and this should be a matter of public health policy. There are difficulties identified with research in the field of health promotion, specifically for health education for homeless persons (Jahan, 2012).

There is absence of implementation evidence in health promotion practice and absence of use of evidence while developing promotional strategies. There are specialized challenges in assessment of health promotional strategies. For performing assessment of health promotion outcomes, it is essential to characterize and gauge the results of the intervention, as was done in this case. Suitable approaches for assessment of intervention outcomes should be developed and embraced. To enhance the quality of studies in the health educational programs, researchers and other stakeholders should enhance the quality and number of published works, specifically for homeless persons and other marginalized groups.

Despite these drawbacks, health promotions have positively influenced health care outcomes in both private settings and public health initiatives (Jahan, 2012). Various public health accomplishments are credited to health promotion. Some of the most incredible health promotion accomplishments of include immunization; more secure work environments; infectious disease control; diminished mortality rates associated with chronic conditions; safer and more beneficial diets; family arranging and enhanced maternal and child health; fluoridation of drinking water and fortification of some foodstuff; and acknowledgment of health risks associated with tobacco use.

None of these accomplishments would have been conceivable without health promotion (Jahan, 2012). In these examples, clearly, specific achievements associated with homelessness are not defined. Nonetheless, health promotion is a necessary intervention strategy, and empowers individuals to adopt practical solutions to their health needs. Health promotion should be implemented in a team with individuals and requires their committed involvement. It assists communities in enhancing their capacities and their skills to take activities, which promote healthy living. They act in groups to bringing about change and improve outcomes.

While challenges exist for health promotion initiatives, opportunities have also been identified for the same (Jahan, 2012). Various agencies, organizations, and individuals around the globe are focused on health promotion for their communities. World organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and others, continuously highlight the plight of homeless individuals as among the most vulnerable in society. As such, they respond by developing strategies, projects, and activities designed for health promotion. Any health care related visits for different reasons for existing are open doors for wellbeing advancement exercises.

It is particularly critical for homeless individuals who may face difficulties gaining access to care facilities. As such, when they are visited at their shelters, the visits should be used to advance health among the most vulnerable population. Visits for any purpose are an opportunity for health promotion to enhance health outcomes of the target groups. Although immense opportunities for promoting health can be found the existence of current advanced technology and electronic modes of communication, these tools are largely not accessible to homeless persons. Nonetheless, health educators can exploit them to deliver their topics.

As previously noted, it is important that any health promotion initiative ought to be implemented following an evaluation of health needs of the target group. This strategy will not just help distinguish needs but will help with planning and creating interventions as indicated by the needs of the target group and different settings.

The difference of specific groups of homeless persons is clear. In comparison with general health promotion efforts, directed interventions can concentrate on the specific needs of homeless groups, for example, persons without shelter, single parents, adolescent, women, or seniors. It is imperative to conduct further research to determine the key health promotion needs of various homeless groups. Identification of informal communities, networks and the engagement of homeless persons in developmental assessments will identify the places and best methods for delivering health promotion. In this study, the researcher had to identify the best venue to reach homeless persons with health educational promotional program.

That is, it is extremely difficult to offer any interventions for homeless persons without prior planning. Social networks and peer educators, and sources of food and drinks can significantly contribute in health promotion for homeless persons. It all requires any creative strategies, which require careful implementation and assessment. Education appears to be the best initial strategy for homeless persons, who lack basic knowledge on self-care.

The numerous needs of homeless individuals force them into contact with many different support organizations. However, the response of a given organization is frequently narrowly focused and determined by emerging cases, rather than long-term approaches. Yet, the different qualities of these multiagency facilities introduce a genuine chance for collaborative health promotion. For instance, health educators can work with shelter home operators to deliver educational programs to homeless individuals, for instance. These organizations can ensure long-term health promotion for homeless persons by coordinating with relevant stakeholders. Novel primary care stakeholders may offer a perfect discussion to establish procedures, supported by sufficient resources to improve interventions. Shelter services may well take part in health promotion to ensure that many homeless persons are reached during their stay.

Recommendations

Results from this study showed that participants who received this educational program gave overwhelming responses and enjoyed the educational materials left for references and future programs. They were delighted to have these classes and looked forward for more. However, from the discussion, it was established that limited literature is available on health education for homeless persons. Much literature tends to concentrate on multiple health issues homeless persons face, but do not look at educational interventions. As such, researchers should focus on impacts of health education programs targeted at homeless persons as a constituent of health promotion to enhance general health.

Research ought to show that health education programs are important for improving health among homeless persons. It is also shown that delivery and promotion for homeless persons require coordination. Hence, researchers should also work together. There is additionally a need to promote collaboration among all stakeholders.

The health promotion initiatives ought to be research based and target specific groups, for instance, vulnerable men. It is important to appreciate the role of evidence in health care settings. Hence, failure to publish findings on health promotion programs is a major drawback to stakeholders who rely findings to make recommendations on policies. In fact, only one old source, in this case, was directly linked to the subject under homeless health education.

The study shows that health care professionals play a major role in health care promotion among underserved populations. Hence, adaptation to clinical practice ensures that health care professionals play a critical part regarding treatment and education of patients and in promoting enhanced health care outcomes within vulnerable groups. Findings provide a practical basis for implementing policies that support physician engagement for the medically marginalized, underserved homeless persons. Improving the health outcomes of homeless individuals is an important initiative to reduce cases of morbidity and mortality in society. General practitioners, family physicians, and nurses are preferably appropriate to offer care, all-inclusive, and sustained care for homeless patients and to guide multidisciplinary teams.

Strengths and Limitations

Given the limited research on health education programs for homeless persons, this research was extremely useful. The learning was conducted in a normal setting (shelter for homeless persons) and, thus, the results were reliable and not prone to any external influences. It might not be possible to generalize the findings of this study to other homeless facilities because only descriptive statistics was used. It was not always easier to find all participants and, thus, their number kept on fluctuating for every topic across the four months of the study.

Conclusion

The aim of this health educational program was to improve overall health of homeless male at Hope House Residents in Middletown, Ohio. The educational program was implemented for four months using a holistic approach. The results showed an exceptional performance in knowledge gain among participants. The participants who received this educational program gave overwhelming responses and enjoyed the educational materials left for references and future programs. They were delighted to have these classes and looked forward for more. Across the seven areas evaluated, results were excellent demonstrated the desire among homeless persons to learn. As such, these results will enable the development of a new model of primary care for health education programs to improve access to healthcare for underserved homeless individuals.

Health care professionals and researchers could effectively advance to the improvement of health care and outcomes for homeless persons, if homeless shelters and other stakeholders can coordinate their efforts. It is necessary to establish a group of multidisciplinary to support vulnerable people in society.

While outcomes were positive and participants were delighted, limited works exist on outcomes of education programs targeting homeless persons. As such, it was difficult to find current empirical data to support the findings of this study. This study therefore recommended further studies in health care educational programs specifically targeting homeless persons.

References

Ba-Essa, E. M., Mobarak, E. I., & Al-Daghri, N. M. (2016). Hepatitis C virus infection among patients with diabetes mellitus in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 313. Web.

Boston University. (2013). Choosing the right assessment method: Pre-test/post-test evaluation. Web.

Campbell, D. J., O’Neill, B. G., Gibson, K., & Thurston, W. E. (2015). Primary healthcare needs and barriers to care among Calgary’s homeless populations. BMC Family Practice, 16, 139. Web.

Coles, E., Themessl-Huber, M., & Freeman, R. (2012). Investigating community-based health and health promotion for homeless people: A mixed methods review. Health Education Research, 27(4), 624-644. Web.

Costa, S. M., Martins, C. C., de Lourdes, C. B., Zina, L. G., Paiva, S. M., Pordeus, I. A., & Abreu, M. H. (2012). A systematic review of socioeconomic indicators and dental caries in adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(10), 3540–3574. Web.

Culo, S. (2011). Risk assessment and intervention for vulnerable older adults. British Columbia Medical Journal, 53(8), 421-425.

Grabovschi, C., Loignon, C., & Fortin, M. (2013). Mapping the concept of vulnerability related to health care disparities: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 94. Web.

Jahan, S. (2012). Health promotion: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Health Education Research & Development, 1, e105. Web.

Jego, M., Grassineau, D., Balique, H., Loundou, A., Sambuc, R., Daguzan, A.,… Gentile, S. (2016). Improving access and continuity of care for homeless people: How could general practitioners effectively contribute? Results from a mixed study. BMJ Open, 6(11), e013610. Web.

Knowlton, A. R., Nguyen, T. Q., Robinson, A. C., Harrell, P. T., & Mitchell, M. M. (2015). Pain symptoms associated with opioid use among vulnerable persons with HIV: An exploratory study with implications for palliative care and opioid abuse prevention. Journal of Palliative Care, 31(4), 228–233.

Lin, W.-C., Bharel, M., Zhang, J., O’Connell, E., & Clark, R. E. (2015). Frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations among homeless people with Medicaid: Implications for Medicaid expansion. American Journal of Public Health, 105(S5), S716-S722. Web.

Maness, D. L., & Khan, M. (2014). Care of the homeless: An overview. American Family Physician, 89(8), 634-640.

May, K. M., & Evans, G. G. (1994). Health education for homeless populations. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 11(4), 229-37. Web.

Noel, C. W., Fung, H., Srivastava, R., Lebovic, G., Hwang, S. W., Berger, A., & Lichter, M. (2015). Visual impairment and unmet eye care needs among homeless adults in a Canadian City. JAMA Ophthalmology, 133(4), 455-460. Web.

O’Toole, T. P., Johnson, E. E., Aiello, R., Kane, V., & Pape, L. (2016). Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: The Veterans health administration’s “homeless patient aligned care team” program. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E44. Web.