Jacques-Louis David is a famous French artist that is considered to be one of the brightest figures and initiators of the neoclassical movement in the art. His works were inspired by classical Greek and Rome paintings. From those times, he adopted techniques and some themes. However, Roberts writes, “his (Jacques-Louis David) lifetime of seventy-seven years coincides with the most tumultuous period of history that France and the Western world had yet experienced” (3).

Transforming the classical tendencies, David managed to capture and express the moods of that time in a majority of his paintings. He was very close to key figures of the French revolution and many of his works are devoted to this theme. He depicted the heroes of that Revolution giving them a bright “masculine” trait and impressive look of ancient gods.

His prerevolutionary work, as well as the works painted during the Revolution, are often interpreted as ones marked with “feminine” or “masculine” traits. It is no wonder as his works were inspired by the traditions of the Classical painters. The “femininity” and “masculinity” are expressed not only through the figures of people, but through themes, colors and other minor details that form a general image of David’s pictures.

The most “sound” in the context of “femininity” and “masculinity” are the pictures The Oath of the Horatii, The Death of Socrates and The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Songs (“masculine”) and The Paris and Helen and The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis (“femininity”). The analysis of these works gives the understanding of the neoclassical art in terms of interpretation of the classical traditions in it.

As it has already been mentioned, Jacques-Louis David was one of the first and leading neoclassical artists in France. His works were inspired by classical tradition. These traditions were expressed through antique subjects, heroes and techniques which he used in his paintings.

“More than any other painter it was David who gave artistic form to the ideas of those days and he did so as a member of the Academy. The style that he brought to maturity in the years before Revolution brought him success and fame”. (Roberts 11) David studied classics in Italy and when he returned to Paris, he promoted anti-Rococo ideas.

He became very famous. The works of this period were filled with devotion to one’s duty, sternness and self-sacrifice. He supported Revolution and many of his works express this idea being propagandistic ones. After the Revolution, David became a court painter. The works of this period glorified Napoleon (The Coronation of Napoleon). After the fall of the Republic, the artist went to Belgium.

The paintings created there were devoted to mythological scenes, “David would turn his attention so completely to the theme of love in his Brussels mythological paintings, for only twice in his entire previous career did he deal with mythical love themes in major painted compositions” (Johnson 37-38). The works of this period are the most “femininity” colored than others creations of the author.

Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces is the last of his greatest works which he finished not long before his death. If one has a look at his works, he/she will see how much the artist relied on the ancient traditions, history and ancient myths. They were the source of inspiration for almost all of his works. At the same time, we cannot say that his works are stable.

His techniques alerted and changed during his career. Actually, there were no artist in France whose works reflected the political climate of the country so clearly. The reason is that for David his paintings were the major means of communication and reflecting his ideas. In general, the works of Jacques-Louis David are the greatest works of the neoclassical movement in France.

Neoclassicism was a major art movement at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. One of the peculiarities of this movement was the addressing to the traditions and themes of the ancient classical works by Roman and Greek artists. Neoclassical movement adopted the classical ideas of moderation and order.

“Reason” directed artistic creation. There were no much emotion in these pictures and all artistic works were organized very logically. In France, the principles of the classical paintings were used and interconnected with the political concerns associated with the Revolution. The neoclassical themes were often based on the classical stories and heroic male virtues.

The themes of pictures which depicted men and women were strikingly divided. Women were mainly presented in the pictures that depicted domestic life or private sphere. In contrast, male figures were used in heroic pictures or performing certain public roles. This sharp division between male and female was reflected in the neoclassical painting style as well. Not only the subjects of the pictures were different for men and women, but the techniques and colors as well.

The “male” paintings used a very rational composition, strong severe colors and rather strict lines. The figures of male were massive and reminded the figures of antique sculptures. Conversely, the colors and techniques of the “female” paintings were softer and brighter. The figures of women were marked with more curvilinear forms.

The neoclassical art is often called “male” art. This tendency has a historical explanation. The political situation that was often reflected in the works of art, burdened the male body with political and social meaning. Men should be a fighter and woman – a keeper of piece.

The neoclassical attitude to the “male” and ‘female” pictures are also present in works of Jacques-Louis David. This tendency of division is best recognized in his works of the Brussels period when he addressed to the antique myths and those of the prerevolutionary period, the period of Academia. His new style was characterized by strict lines, symmetry and strong gestures of figures depicted on them. This style is perfectly seen in the picture The Death of Socrates.

Moreover, this is one of the works that is considered to be a “masculine” one. Each detail reflects its masculine nature: the light, colors, settings and many other artistic elements. One of the major means that David uses in order to accentuate the “masculinity” of his pictures is the light and “freeze-like” composition and serious subjects. The “femininity” of the paintings was expressed through the light colors, such as the dominance of pink and pastel-like shaped.

The outdoor setting and emotional subject are more frequent in such pictures. The best example of the “feminine” motives in the David’s paintings are the pictures of the Brussels period that depict mythological themes, “mythological episodes are the best vehicles for expression of complex psychological and emotional situations, compositions that would be pertinent and relevant to contemporaneous cultural values and concerns” (Johnson 80).

As it has already been mention, the David’s pictures reflect the tradition of neoclassicism to separate “masculine” and “feminine” paintings:

“In the year leading to the outbreak of the French Revolution, Jacques-Louis David painted a series of austere, “masculine” paintings: The Oath of the Horatii, The Death of Socrates and The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Songs. Although the precise meanings and political significance of the “austere” paintings are controversial, their moralizing content has not been questioned. The three works deal with masculine heroes engaged in high-minded self-sacrifice for transcendent value of patriotism and conscience, and they have been taken to represent the true spirit of David in those years of political unrest” (Korshak 102).

As a contrast to these pictures, The Paris and Helen and The Farewell of Thelemacus and Eucharis can be taken.

What is so “masculine” in the pictures like The Death of Socrates and The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Songs?

According to the traditions of neoclassicism, the action of the picture The Death of Socrates takes place indoors. The distribution of light and dark is very strict. Such distribution of light gives a possibility to show the Socrates’ “god features” and helps us understand that he suffered from the illness.

Despite his suffering, the man has an ideal proportions of the body and he preserves calmness and self-control(another feature of the “male” pictures). The colors are dark and the position of Socrates is tense. The position of other people in the picture also has its meaning, “in this scale, placement, color, and sensual attractiveness, the anonymous cupbearer has become a balancing element of the composition, equal to the figure of Socrates himself” (Perry and Rossington 212).

This picture had a great political context on the eve of Revolution. Another example of the “masculine” painting is the The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Songs. However, in this picture we can observe both, male and female traits, “the composition of the Brutus is streaky divided into male and female halves, so an exclusive male world remains at the left, but survives only in shattered form” (Perry and Rossington 215).

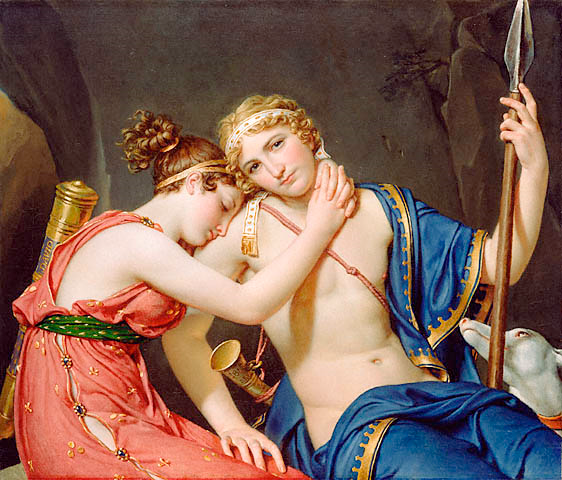

The left side is dark and calm, there are no emotions. And only the left side which depicts a woman with her children show the emotions that are possible in the female world. The colors are also bright. Such use of light on the right side elevates the emotional tense of the painting. The “female” pictures, The Paris and Helen and The Farewell of Thelemacus and Eucharis depict emotions.

As Yvonne Korshak mentions, “David’s Paris and Helena has received little attention, largely because it seem anomalously unphilosophical and “feminine” in the context of the artist’s other stoic, “virile” prerevolutionary paintings” (1). The picture is tender, it shows love of two people “in their love nest”. The presence of Cupid supports the atmosphere of love.

The couple is surrounded by an antique setting. The emotional tone, as well as compositional, are calm, in spite of the fact that Cupid and the lamp are eliminated. The colors are not bright, but soft. It is a classic “female” picture, as it shows emotions and feeling of love, the line and the colors are soft, as well as the lightning. Finally, The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis is another example of the “female” painting.

The central here is the psychology of love. The story of the picture contains a sentimental depiction of two lovers taken from the Odyssey. It is very emotional picture, “it inspired a number of lyrical, melancholy depictions of hapless mythical lovers that emphasized the psychological dimension of the narratives portrayed” (Johnson 91).

The picture shows the intimate and tender farewell in the dark cave, they are surrounded by darkness, only their figures are eliminated and it evokes the feeling of intimacy. The colors are deeply saturated: the man is in blue (cold, “masculine” color) and young girl is in red (warm, “female” color). Thus, it is a typical “female” picture with all signs of its type.

Jacques- Louis David was an outstanding French artist. He is considered to be the founder and the brightest representative of the neoclassical art movement. His works were inspired by the traditions of the ancient Roman and Greek world. He adopted the strict lines, traditions of moderation and order.

Apart from the classical techniques, David created paintings which depicted ancient myths and ancient heroes. The peculiarity of the neoclassical painting style is the division on “masculine” and “feminine” pictures. Each of these types had its peculiarity.

The “feminine” pictures depicted emotions and used soft colors and lines. Among the works of David, there are bright examples of this division. These works are The Death of Socrates and The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Songs (“male” ones) and The Paris and Helen, The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis are the examples of “female” pictures.

Works Cited

Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David: The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. Los Angeles: Getty Museum Studies on Art, 1997.

Korshak, Yvonne. “Paris and Helen by Jacques Louis David: Choice and Judgment on the Eve of the French Revolution”. The Art Bulletin Vol. 69, No. 1, (1987): 102-116.

Perry, Gillian, and Michael Rossington. Femininity and masculinity in eighteenth-century art and culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Roberts, Warren. Jacques-Louis David, Revolutionary Artist: Art, Politics, and the French .Revolution. United States of America: The University of North Carolina Press Books, 1992.