Introduction

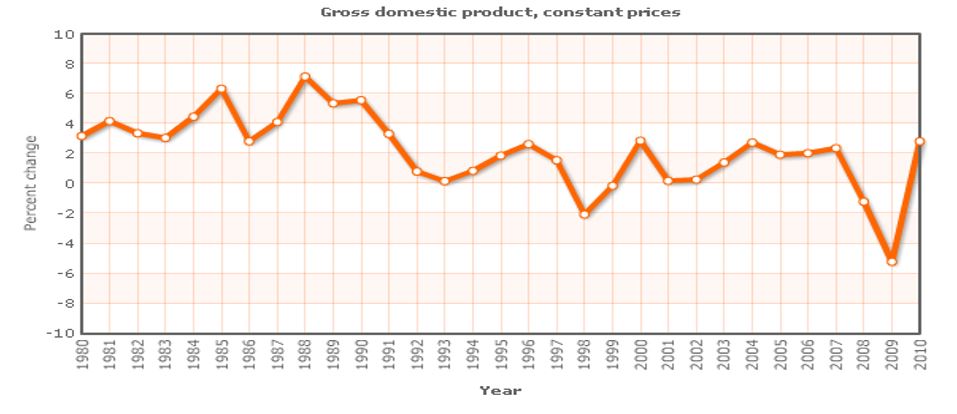

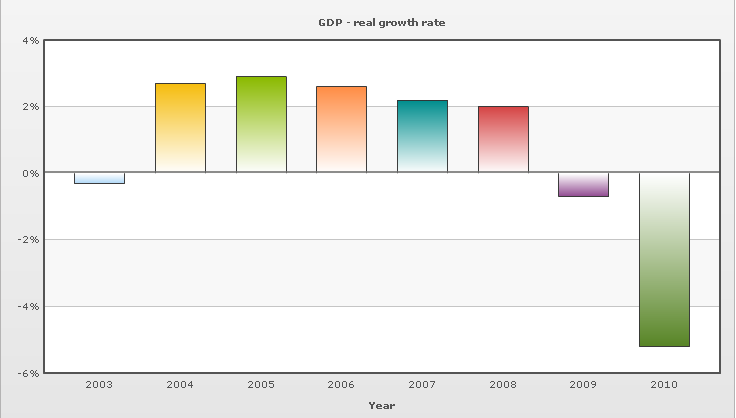

The economy of Japan is considered the most controversial still a rather captivating and educative aspect of Japanese development. Japanese achievements are not that higher in comparison to those of the United States of America and China, still, the history of Japanese economic development has to be considered. According to Teranishi (2005), the economy of this particular country has become noticeable due to “various Japanese-style properties: a firm system based on seniority wages and life-time employment, a bank-dominated financial system with an active role for main banks, heavy government involvement through industrial policy” (p.3). There are three main periods in the history of theJapanese economy after the World War Second: the time when “the Japanese economy lay in total ruin” (Maswood 2002, p. 1), the “economic miracle” (Kopstein & Lichbach 2005), and the lost decade that is known as the period of considerable economic slowdown with numerous inability to take the control over the banks’ actions. The changes which are observed with the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to predetermine the economic well-being help to realize how significant each period for Japan was. In the Table One, the graph of how GDP varied during the period between the 1980s and the 2010s aims at showing how dramatic the changes could be: unbelievably high rates were observed in 1988 as a result of the post-war miracle that contained effective cooperation of distributors, manufacturers, and banks, numerous unions of powerful enterprises, and lifetime employment and gradual decline that was inherent to 1998 due to the already supported ideas of bank speculations and inabilities to cope with massive borrowings. However, the results achieved tin 2009 prove that the slowdown observed in 1998 was not the most terrible period in Japanese economy.

This is why it is very important to evaluate and to understand the essence of the idea offered by Klingner & Scissors (2009) who admitted that to call the period of 1990s as the lost decade in Japan “is a mistake – the loss has extended well beyond the 1990s. The economy is now smaller than it was the first quarter of 1991, so Japan is actually approaching its second lost decade”. Of course, it is important to choose the steps and make everything possible to overcome the current crisis. However, it is also necessary to realize how to support the recovery for some period of time and overcome the challenges the way they will never bother the country in the nearest future. Japan introduces the example of how radical steps may negatively influence the development of the country’s economy.

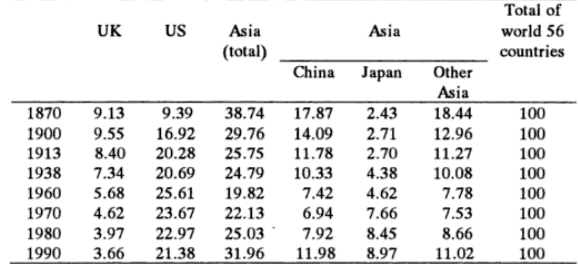

In comparison to other countries which may compete with Japan to take the leading position, it is necessary to define the United States as the world leader and China as the Asian leader. As Teranishi (2005) pointed out that “the Japanese economy experienced a relatively high rate of economic growth, as evidenced by an increasing share of world GDP” for a long period of time (p.11). In Table Two, it is possible to observe the rates of Japan GDP as well as the rates of different countries during more than a century. These calculations show that Japan is one of the countries that did not take some catastrophic and unpredictable steps. Their rates are always gradually arranged:

In fact, it is evident that the ‘lost decade’ expanded considerably during the last years, and it is difficult to define its boundaries. This is why it seems to be effective to investigate the macroeconomic and microeconomic aspects over the last decade and explain the essence of structural and monetary activities taken by the Japanese representatives to save their economic sphere and gain benefits from their investments. Japan has evaluated the conditions under which it has to be developed and found out that certain changes have to be made on a microeconomic basis: the implementation of the structural reform should lead to numerous benefits which help to revitalize the Japanese economy, to enhance the growth, and to secure the desired recovery within the shortest periods of time. In spite of the fact that the Japanese economy remains to struggle with the structural reforms which are dated from the beginning of the 1990s, the existed deflationary gap becomes an intrinsic dilemma in the economic order. As Gao (2001) says the chosen economic dilemma has to reveal the mechanism with the help of which the institutional change and some kind of exogenous shock may be linked logically.

Main Body One

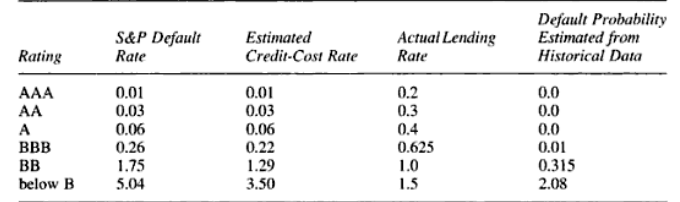

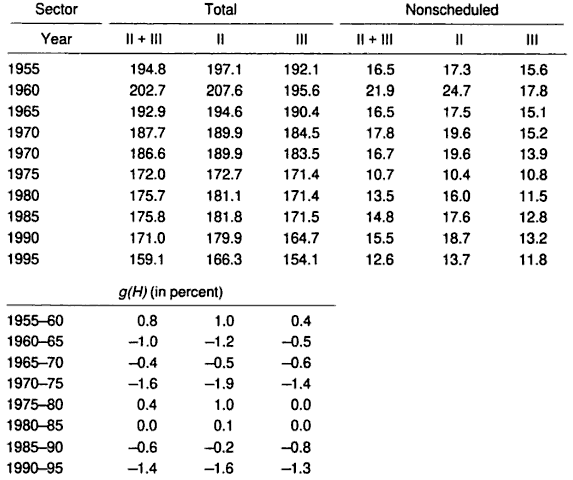

Numerous microeconomic activities in Japan are usually based on the reforms which aim at improving the productivity and changing the structural aspect of the economy (Sato 1999). Japan as many other countries like the USA, the UK, or even Australia made an attempt to rely on the best practice microeconomic policy and open up different markets to competitions with the help of which the process of restructuring could be possible. The example of the most successful structural reform was offered by Lin in 2005. The ideas introduced were based on the possible cooperation between the American and Japanese representatives in the form of an interior equilibrium (Lin 2005). This equilibrium is formed by means of the weakest keiretsu that are the banks, manufacturers, and distributors which have been united during the period of the Japanese economical miracle united in order to improve the economy (Australian Government 2005). In the Table Three, the results show that banks of different levels underwent considerable changes during the post-war period, and the actual lending rates which are based on the borrowings offered are not stable.

Numerous keiretsu unions are able to ensure the collaborations to invest in the development of the Japanese economy. Still, they are not powerful enough to provide the member with long-term profitability (Kim 1998), this is why it is necessary to make use of the main bank that has governmental support as well as a good reputation on the world market.

To struggle with the structural problems, Japan should also evaluate overseas markets in order to compensate for the necessary amount of domestic industries. Export and import of Japan were small during the ‘lost decade’, and it was obligatory to increase the rates of trade both export and import. And it is possible only in case of transformation of the industry and the structure of the trade in order to become more reliant. It is not enough to focus on the automobile or electronic industry that is popular in Asian and European countries. However, the improvement of cosmetic, food and sundries manufacturing will be more appreciated by the competitors.

To understand better the essence of the economic problems and choose the most appropriate steps, it is crucially important to realize the reasons and the challenges which made Japan neglect the success of the bubble-driving miracle, be overwhelmed with the speculations as well as suffer because of stagnation. The observations made by Dasgupta (2009) help to understand that the period of ‘lost decade’ is considered to be an economic as well as socio-cultural change in Japanese history, this is why the changes and difficulties should be evaluated from all these three perspectives. Collective socio-cultural anxiety is one of the reasons why Japan could not continue its economic development during the 1990s. At the beginning of the 1990s, Japan lost its national confidence; this is why certain shifts took place. In addition to personal uncertainty, Japan has to solve the challenges which came from the United States. “America’s comeback was bound up with an orthodox economic strategy of fiscal prudence and continued economic openness, reinforcing central premises of the tree traders” (Kunkel 2003, p. 193). Constant American involvement in Japanese economic activities prevented the required development and improvement of the conditions under which the lost decade was able to develop considerably. It was hard to control the financial activities which predetermined the relations between different keiretsu as well as between the international potential partners. It was clear that some American demands could not be understood and considered by the Japanese representatives, still, it was defined that American pressure may lead to the required success and productivity. “With Japan no longer much of an economic competitor and the U.S. also grappling with the financial crisis, Tokyo could offer reciprocal proposals with some chance of seeing them accepted by Washington” (Klingner & Scissors 2009). In other words, the American push may be of formal or informal nature in order to reduce the dependence of the Japanese economy on the weak export and focus on the domestic economy.

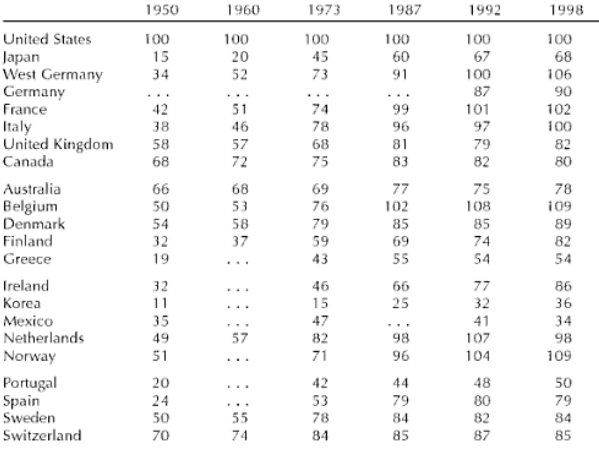

Still, the investigations show that American impact on different countries remains to be a serious challenge for such OECD countries like Japan. Even if Japan takes first place among other countries evaluating the productivity levels, the manufacturing levels remain to be smaller. The potential impact of structural reforms on productivity growth is not easy due to the problems with the regulations on the economic performance from America’s side. Still, a number of attempts have been already made to support the economic development; though the results are a little bit sensitive (Callen, Ostry, & International Monetary Fund 2003), Table Four shows that Japanese attempts are still the most successful.

Main Body Two

Microeconomic reforms taken during the lost decade to improve the conditions got were usually directed towards considerable improvement of living standards. The way of how this improvement could be achieved was closely connected to the increasing of productivity and efficiency and some macroeconomic impacts which have to be admitted. During the 1990s, Japanese account deficit and growing debts due to constant borrowings attract attention. Many people truly believed that microeconomic reforms will reduce the deficit spreading over the county. Taking into consideration the changes which took place with the Japanese banks and corporations at the microeconomic level, it was important to take the steps which could improve the conditions from the inside at the macroeconomic level. This is why in addition to the outside structural changes; the decision to change the working conditions was made. Macroeconomics is the field that deals with the economic behaviour, and the change of Gross National Product is usually predetermined by the changes in employment and working conditions. Microeconomic change based on working hours may lead to the desirable changes of macroeconomic policy, this is why much attention was paid to the working hours. Sato (1999) admits that “when the slow growth period started, hours declined to around 175 hours per month or 2,100 per year” (p. 35); and before that period, working hours were about 200.

The chosen reform should make some Japanese tradeable industries more competitive: costs were reduced, workers’ needs were met so that they were inspired enough to offer more brilliant ideas for improvement.

Unfortunately, it seemed to be very difficult for the government that has a significant portion of control to take the steps and improve the macroeconomic policies such as monetary and fiscal reforms (Itoh 2010). The point is that the Japanese people will hardly allow some uncontrolled tax increase in case they are not confident in the possibilities of their government to cut down all wastes sufficiently. This is why the government should create a proper plan to encourage fiscal restructuring and to promote long-term sustainability that will touch upon all aspects of the Japanese economy. Such confidence is required to promote appropriate recovery as well as support the country after the recovery is successfully passed.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the makers of macroeconomic policies in Japan underwent certain challenges which have domestic and international origins. Japanese fiscal policy was characterized by numerous economic weaknesses caused by passivity and the desire to avoid risks within a short period of time. However, Japanese indecision in the economic field deprives this country of making some decisions independently. This process is based on the investors’ opinions who find the way and remain to be large shareholders (Cohen 2001). Grimes (2001) admits that “Japan’s macroeconomic pathologies have included an excessive reliance on monetary policy to solve large-scale macroeconomic problems and an extreme aversion to loosening fiscal policy”, and it is very important to underline that all “these pathologies were not the result of incompetence or corruption on the part of policymakers; rather, they were structural in nature” (p. xviii).

The last decade was rather educative for Japanese economic policymakers. First, their mistakes made them re-evaluate their possibilities and their relations with different countries. What the Bank of Japan did was wait until it was too late to take some steps and improve the situation about the incipient deflation problems (Siebert 2004). The results of such inabilities to evaluate the current conditions and learn from the activities taken and the mistakes made were expected: the real growth rate decreased considerably within a short period of time. In Table Six, a dramatic fall may be observed.

Taking into account the results identified and the conditions under which the Japanese people have to live today Flath (2005) and some other researchers are bothered with one and the same question: whether such mistaken macroeconomic policies did cause the mess. Well, it is true that fiscal policy and the changes within it may cause fluctuations in aggregate demand that leads to recessions. It becomes clear from the following example how aggregate demand may be changed: interest rates are bid up, and citizens are not that interested to be enriched by means of non-interest-bearing money (Flath 2005). And such ignorance of money-making results in a significant increase in aggregate demand. And in case the interest rate falls suddenly, the desire to hold wealth in the money form increases, and aggregate demand decreases. And the Japanese government failed to act quickly as soon as the Bank of Japan got into trouble: disclosure of loan problems should gain priorities to define the correct measurements (Matsuda 2000).

Conclusion

In general, the lost decade in Japan serves as one of the most educative and captivating period to deal with. A number of macroeconomic and microeconomic policy-making processes are observed, and the purpose of each policy is unique. Still, all of them aim at improving the economic situation of the country and identifying the weaknesses which prevent the development. The nature of the lost decade is rather clear: after a considerably growth in numerous spheres at the same time, the Japanese people believed that they had huge powers and the banks believed in their abilities to provide many people with the required economic support and financial aid. However, the banks failed to protect the economic bubble developed, and the result was evident: the termination of the bubble and the huge crash in stock markets. It was not enough for the country to choose the most effective steps and take all of them quickly. It was much more important to take the leading position in the world arena and make other countries admit the power of Japan economy. And the Japanese people made a decision to enrich themselves due to the existed low interest rates and huge land values; and as a result of such actions, a number of borrowings were taken at the expense of foreign stocks and the banks had to under the governmental control. Taking into consideration the borrowings offered, it was hard to overcome the debt crisis: banks became unable to cope with the borrowings, this is why they was obliged to bailed out by the Japanese government. The outcomes were evident: rise of unemployment, necessity to take reforms, and change of working hours. People were in need of some changes to understand their worth and to realize their abilities, and the period called the lost decade was the time when it was obligatory to identify the changes and the needs of the Japanese people. The way of how the Japanese government was able to react to the crisis was all about the revival of growth. The activities chosen by different organizations such as investments and money-making by means of interest rate are the most successful examples of how policymakers may improve the situation. The structural reforms are taken, numerous deregulations and resolutions of the financial crisis are considered to be important elements of the period under discussion. These ideas help to remove the obstacles and cope with the challenges which are usually based on economic globalization. It is difficult to avoid the economic challenges from time to time, still, it is always possible to choose the most effective approaches and take them into account each time the innovation or reform is offered.

Reference List

Callen, T, Ostry, JD, & International Monetary Fund 2003, Japan’s Lost Decade: Policies for Economic Revival. International Monetary Fund, Washington.

‘Changing Corporate Asia: What Business Needs to Know’, 2005, Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs Trade. Chapter 6: Japan. Web.

Cohen, SI 2001, Microeconomic Policy. Routledge, New York.

Dasgupta, R 2009, ‘The Lost Decade of the 1990s and Shifting Masculinities in Japan’, Culture, Society, and Masculinities, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 79-95.

Flath, D 2005, The Japanese Economy. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gao, B 2001, Japan’s Economic Dilemma: The Institutional Origins of Prosperity and Stagnation. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Grimes, WW 2001, Unmaking the Japanese Miracle: Macroeconomic Politics, 1985-2000. Cornell University Press, New York.

Itoh, M 2010, ‘The Japanese Economy: Tackling Structural Problems’,East Asia Forum. Web.

‘Japan GDP: Real Growth Rate’, 2010, Index Mundi. Web.

Kim, AK 1998, ‘A Test of the Two-Tier Corporative Governance Structure: The Case of Japanese Keiretsu’, Mark Journal of Financial Research, vol. 21.

Klingner, B & Scissors, D 2009, ‘Japan’s Economic Weakness: A Security Problem for America’,The Heritage Foundation. Web.

Kopstein, J & Lichbach, MI 2005, Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Kunkel,J 2003, America’s Trade Policy Towards Japan: Demanding Results. Routledge, New York.

Lin, C 2005, ‘The Transition of the Japanese Keiretsu in the Changing Economy’, Journal of Japanese and International Economies, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 96-109.

Maswood, SJ 2002, Japan in Crisis. Palgrave MacMilan, New York.

Matsuda, K 2000, ‘Lessons from Japan’s Lost Decade’, ABA Banking Journal, vol. 92, no.9, p. 128.

Sato, K 1999, The Transformation of the Japanese Economy. East Gate Book, New York.

Saxonhouse, G, Stern, RM, & Saxonhouse, GR 2004, Japan’s Lost Decade: Origins, Consequences and Prospects for Recovery. Blackwell Publishing, Malden.

Siebert, H 2004, Macroeconomic Policies in the World Economy. Springer, New York.

Teranishi, J 2005, Evolution of the Economic System in Japan. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton.