Introduction

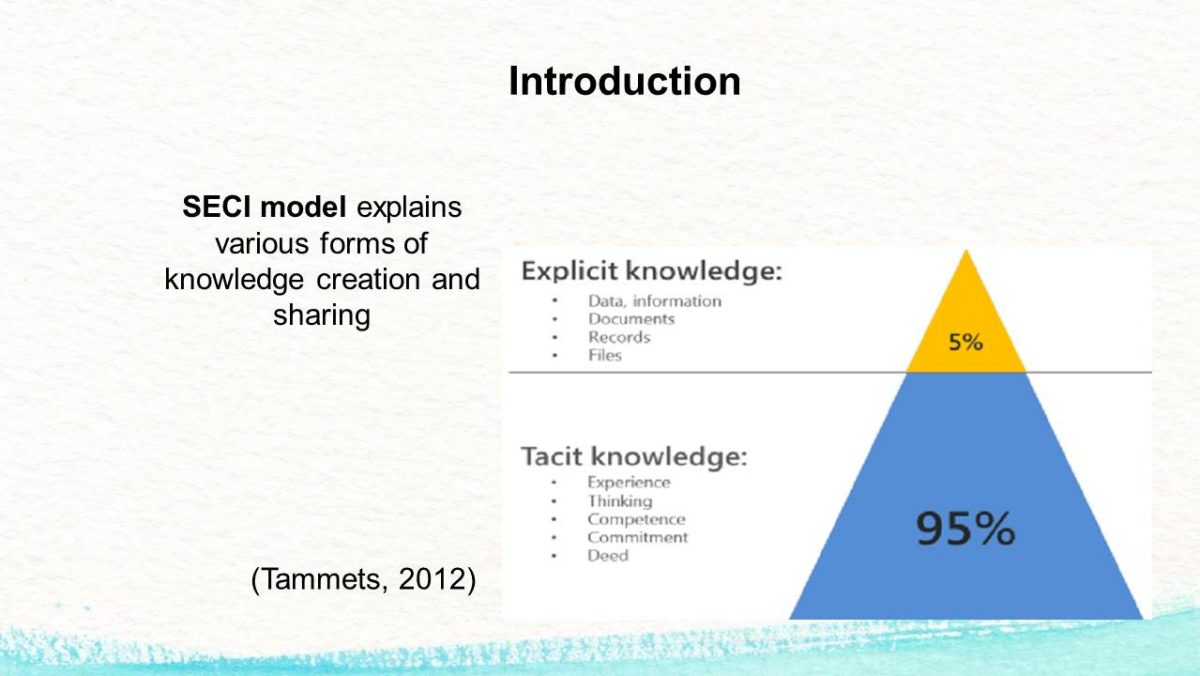

SECI model explains various forms of knowledge creation and sharing:

- Explicit knowledge:

- Data, information;

- Documents;

- Records;

- Files.

- Tacit knowledge:

- Experience;

- Thinking;

- Competence;

- Deed.

This presentation focuses on the description of the mentioned concept. In particular, such issues as the origin and the essence of the model, different knowledge conversion processes as well as advantages and limitations will be considered. More to the point, the presentation will include some real life examples to illustrate the SECI model and make it comprehensible to the viewers.

What is the SECI model?

According to Nonaka, the originator of the model, the creation of knowledge is an abstract spiral process of interaction between explicit and implicit (tacit) knowledge, which leads to the emergence of the organisational knowledge (Tammets, 2012).

In 1995, Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi described a model of knowledge creation process for understanding the dynamic essence and ensuring its effective management. On the basis of the classical division of knowledge into explicit and tacit modes, the professor Nonaka assumed a theory of knowledge creation called the SECI model.

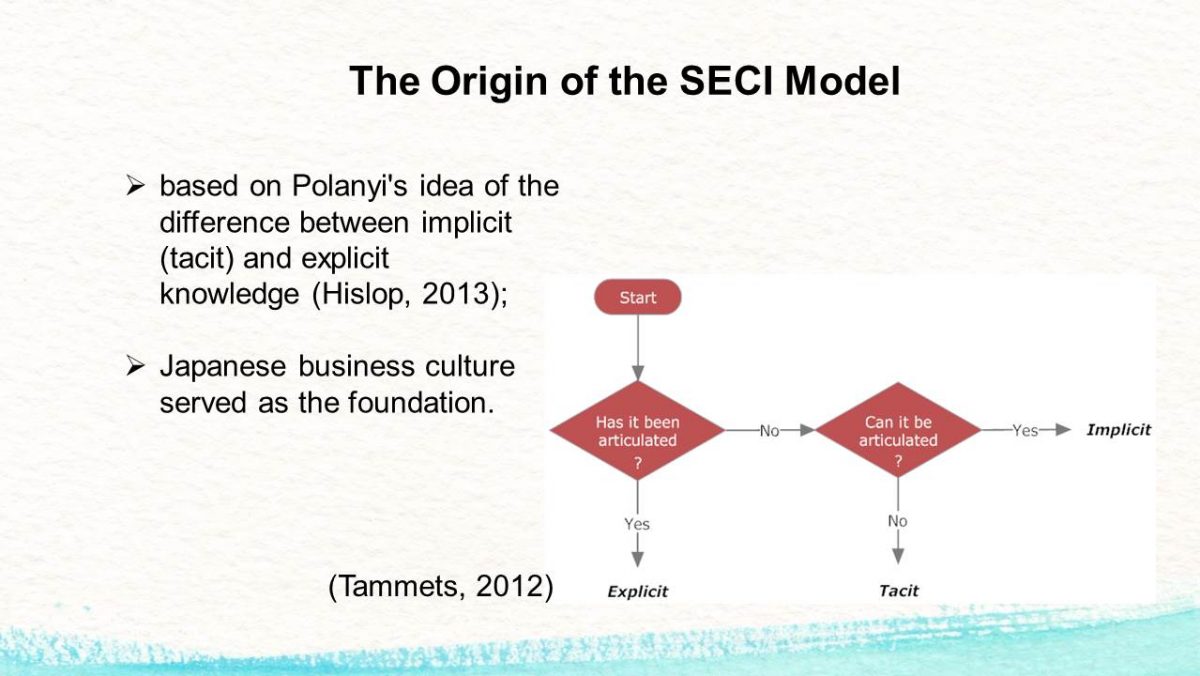

The Origin of the SECI Model

- based on Polanyi’s idea of the difference between implicit (tacit) and explicit knowledge (Hislop, 2013);

- Japanese business culture served as the foundation.

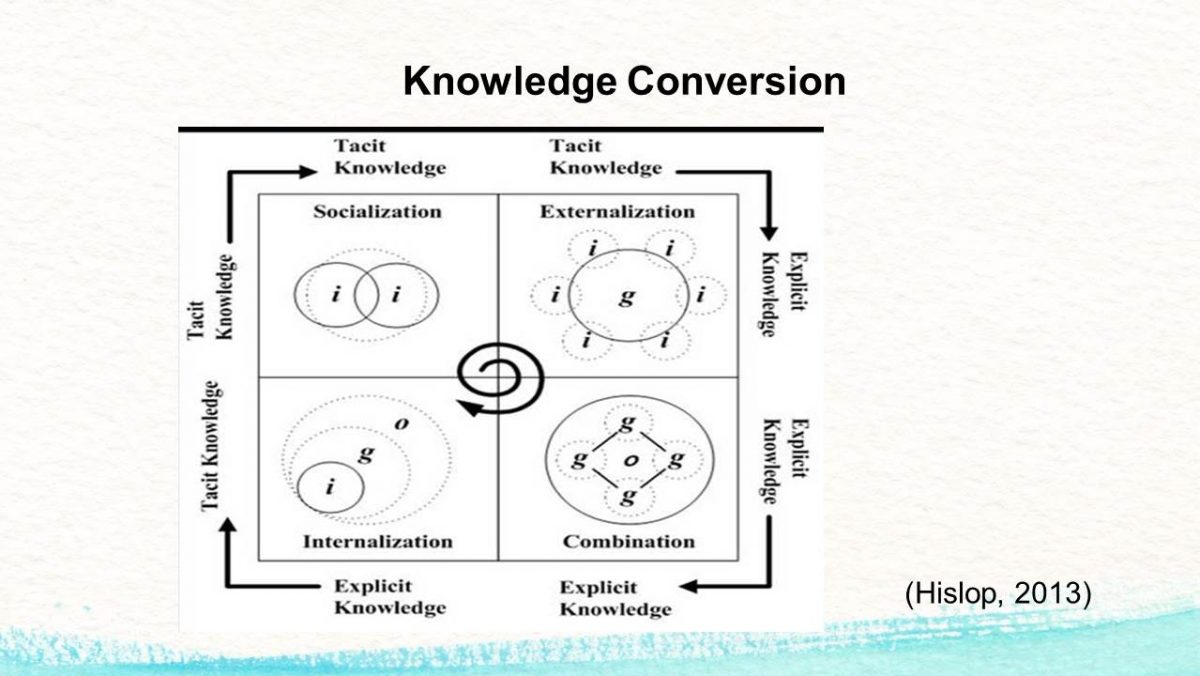

Knowledge Conversion

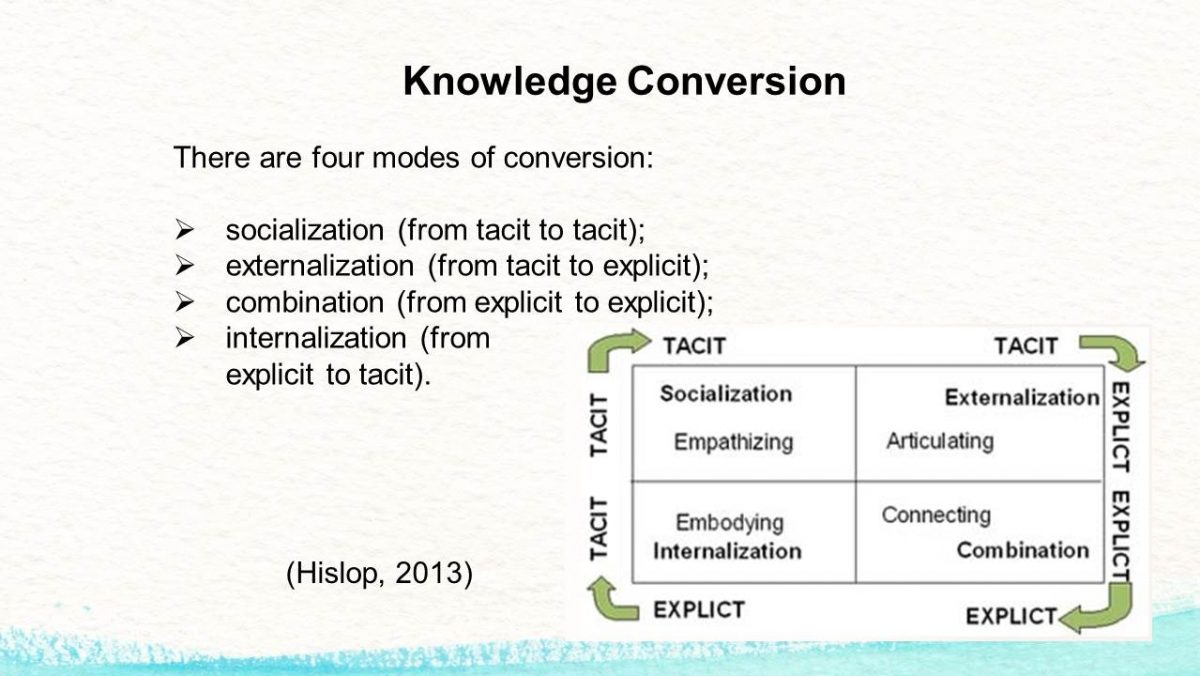

There are four modes of conversion:

- socialization (from tacit to tacit);

- externalization (from tacit to explicit);

- combination (from explicit to explicit);

- internalization (from explicit to tacit).

Nonaka called the social processes occurring between individuals the conversion of knowledge. The creation of knowledge is a continuous process of the dynamic interaction between implicit (tacit) and obvious (explicit) knowledge. Four knowledge transformation modes interact in knowledge creation spiral. The spiral grows in scale as it moves through the organisational levels and can trigger new spirals of knowledge creation (Lindlöf, Söderberg, & Persson, 2013). In this case, there are four options for transforming one type of knowledge into another: socialisation (from tacit to tacit), externalisation (from tacit to explicit), combination (from explicit to explicit), and internalisation (from explicit to tacit). The first letters of the names of processes compose the name of the model.

Socialisation, the transformation of knowledge from the tacit into the similar, implies the transmission of knowledge to other people. An example is training. For instance, tacit knowledge may include beliefs, values, ideas, and the very way of thinking – some abstract concepts that are difficult to formalise. Therefore, to implement the process of socialisation, according to Gavrilova and Andreeva (2012), it is necessary to create such conditions for the exchange of experience, in which both senders and recipients of implicit knowledge can spend more time in terms of open communication.

Externalisation is the process of transforming implicit knowledge into explicit one, which is accomplished by means of offering the former knowledge in such a way that would be understandable to other people. For externalisation, it is necessary to possess special techniques that help to express explicit knowledge. It can be models, metaphors, visual forms, etc. In addition, externalisation is initiated by dialogue or collective reflection, using analogies that help team members to reveal their informal knowledge and create conceptual knowledge.

- Socialization. It refers to sharing knowledge through direct communication or common experience.

- Externalization. Development of concepts that contain the combined implied knowledge and ensure its communication.

- Combination. The combination of various components of explicit knowledge.

- Internalization. It is close to the concept of learning in action.

Combination, the transformation of knowledge from explicit to explicit knowledge, is a process, in which clearly expressed and systematised knowledge takes on even more complex forms by becoming a part of a larger system. For example, the creation of a prototype involves various models. People exchange knowledge via meetings, telephone conversations, communication in computer networks, and due to the combination of the above.

At the mode of internalisation, explicit knowledge becomes a part of knowledge base of the individual (for instance, the mental model) and the asset for the organisation (Richtnér, Åhlström, & Goffin, 2014). Internalisation is the transformation of explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge. It implies the interpretation of explicit knowledge, the inclusion of the acquired knowledge in the system of thinking, and the acquisition of additional experience. Internalisation is closely connected with training in practice. When experience through socialisation, externalisation, and combination is internalised into informal knowledge in the form of a common intellectual model or technological know-how, it acquires value, and knowledge from an individual level moves to the level of the organisation. Thus, the cycle of creating knowledge begins a new turn.

Examples: Socialisation

- Matsushita Electric Industrial Company (MEIC);

- a serious problem of the mechanization of the kneading skill;

- Ikuko Tanaka and several engineers voluntarily started training with the senior baker of Osaka International hotel;

- after many unsuccessful attempts, Tanaka realized that the baker not only rolls out, but also twists the dough;

- as a result of socialization, MEIC enhanced its operation.

A new employee learns from a supervisor by not listening to him or her, but observing, imitating, and practising. Tacit knowledge is perceived through experience. Without the perception of experience, it is rather difficult for a person to comprehend the thinking process of another person. The example that demonstrates socialisation of informal technical skills is from the practice of Matsushita Electric Industrial Company (MEIC) can be noted. In the company’s office in Osaka, when developing an automatic bread maker in the late 1980s, management encountered a serious problem of the mechanisation of the kneading skill, which is the informal knowledge of bakers (Easa & Fincham, 2012). Observing experience of the baker, she socialised the informal knowledge of the baker through observation, imitation, and practice. Socialisation occurs between the product developers and owners. The interaction with employees before the product development and after its release on the market is a continuous process of dissemination of non-formalised knowledge.

The socialization process I observed in the workplace was characterized by:

- design of the workplace (job design) allowing employees to share experiences, monitor performance, and imitate others;

- the mentoring system;

- internship with more experienced colleagues;

- creation of an interaction field.

Personally, I observed how socialisation occurred in the workplace. It was characterised by design of the workplace (job design) allowing employees to share their experiences, monitor performance, and imitate others. Moreover, the mentoring system was introduced to help new employees in understanding the job requirements and goals of the organisation. For example, in order to learn how to effectively conduct meetings, a novice manager had an internship with more experienced colleagues, attended their activities, and acquired their tacit knowledge based on informal knowledge of colleagues. Thus, socialisation in this organisation began with the creation of an interaction field. This field promoted the dissemination of experience and intellectual models of employees. Sharing knowledge with team members allowed expanding the boundaries of innovation processes to open access to new knowledge.

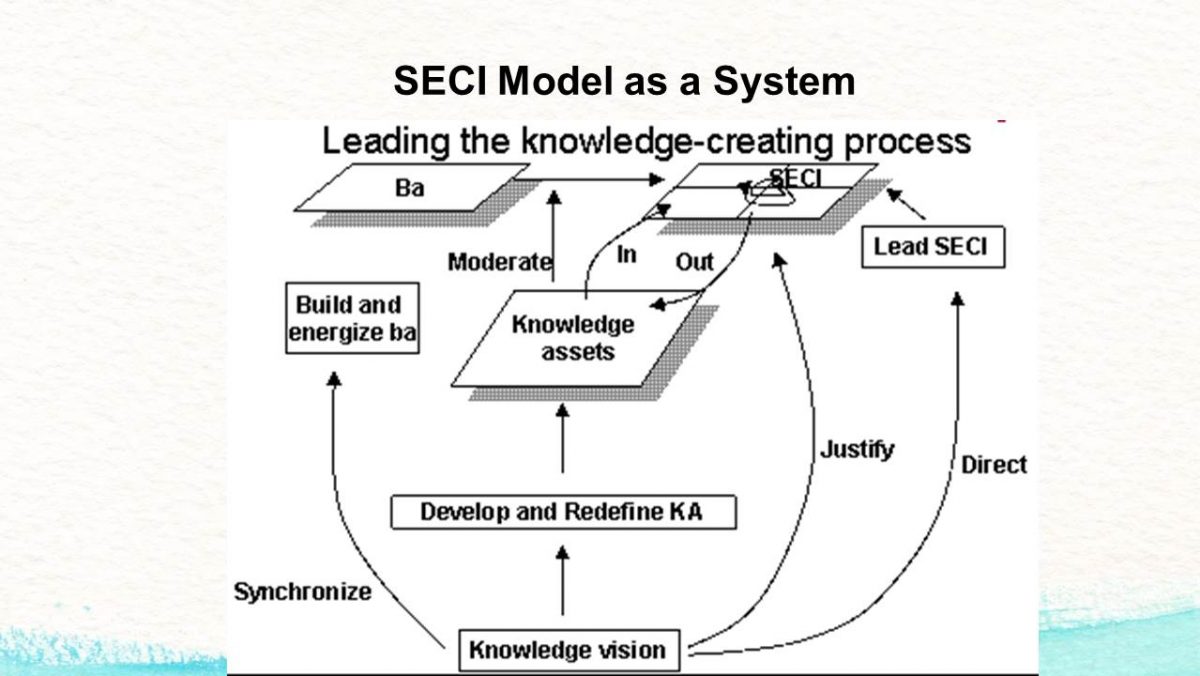

SECI Model as a System

As it was already stated in the definition by Nonaka, the processes described by the SECI model are spiralling in nature. This means that the transformation of knowledge forms a spiral that grows with each new mode conversion passing through all four processes, both in the horisontal and vertical planes, thus embracing new people and knowledge. The space in which this spiral is located, Nonaka calls “ba”, and the knowledge that accumulates as a result of the model’s action is called “assets of knowledge”. These components interact with each other organically and dynamically. The assets of knowledge of the organisation are mobilised and exchanged in ba, whereas the implied knowledge of individual people is transformed and amplified by a spiral of knowledge through socialisation, externalisation, internalisation, combination. The mentioned components should be integrated with clear leadership, so that the organisation can continuously and dynamically create knowledge. They should compose a discipline for the members of the organisation.

Advantages

- Considers the essence of knowledge and the creation of knowledge in a dynamic format (Becerra-Fernandez & Sabherwal, 2014; Meihami & Meihami, 2014).

- Offers a concept for the management of relevant knowledge creation and sharing processes.

Limitations

- The SECI model is based on Japanese organizations that primarily focus on implied knowledge: employees often have a lifetime employment in a certain firm (Hong, 2012).

- Linearity of the concept. It is unclear whether the spiral can jump over the stage and go counter-clockwise or not.

The assumptions regarding the cultural universality of this knowledge management model have been heavily criticised in recent decades. However, the existence of the potential influence of culture, both national and organisational, on the effectiveness of knowledge management cannot be overestimated.

Conclusion

The issues discussed in this presentation can be considered fundamental for the study of knowledge management problems in the organization.

They give an understanding of the essence of knowledge as an object of research, its characteristics, and the principles of its emergence and transformation.

To conclude, it should be emphasised that the theory of knowledge creation and sharing developed by Nonaka has received a huge spread and recognition among experts in the field of knowledge management. The existing approaches to the study of knowledge management were created on the basis of the mentioned ideas about knowledge. Organisational knowledge is created at different levels of the firm. Each employee of the company has valuable knowledge for the firm, which, under certain conditions, can be transformed into knowledge of the department, team, or unit.

References

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2014). Knowledge management: Systems and processes (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Easa, N. F., & Fincham, R. (2012). The application of the socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation model in cross‐cultural contexts: Theoretical analysis. Knowledge and Process Management, 19(2), 103-109.

Gavrilova, T., & Andreeva, T. (2012). Knowledge elicitation techniques in a knowledge management context. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(4), 523-537.

Hislop, D. (2013). Knowledge management in organizations: A critical introduction (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hong, J. F. (2012). Glocalizing Nonaka’s knowledge creation model: Issues and challenges. Management Learning, 43(2), 199-215.

Lindlöf, L., Söderberg, B., & Persson, M. (2013). Practices supporting knowledge transfer–An analysis of lean product development. InternationalJournalofComputerIntegratedManufacturing, 26(12), 1128-1135.

Meihami, B., & Meihami, H. (2014). Knowledge Management a way to gain a competitive advantage in firms (evidence of manufacturing companies).InternationalLettersofSocialandHumanisticSciences, 3(1), 80-91.

Richtnér, A., Åhlström, P., & Goffin, K. (2014). “Squeezing R&D”: A study of organizational slack and knowledge creation in NPD, using the SECI model. JournalofProductInnovationManagement, 31(6), 1268-1290.

Tammets, K. (2012). Meta-analysis of Nonaka & Takeuchi’s knowledge management model in the context of lifelong learning. JournalofKnowledgeManagementPractice, 13(4), 1-18.

Von Krogh, G., Nonaka, I., & Rechsteiner, L. (2012). Leadership in organizational knowledge creation: A review and framework. JournalofManagementStudies, 49(1), 240-277.