Introduction and Background

Knowledge is considered a critical success factor for service-oriented and manufacturing-based organizations and economies (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). Indeed, today, many organizations understand the importance of intellectual capital as a strategic resource for modern-day economies. Thus, a company’s ability to generate, share and preserve intellectual capital is deemed an area of strategic competitive advantage (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). To capitalize on the strengths and importance of knowledge to modern societies, companies need to ensure it is freely shared through knowledge sharing.

Knowledge exchange is an independent discipline that falls under the concept of intellectual capital management (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). Such systems exist because intellectual capital is commonly confined within specialized domains. Different researchers have unique conceptions of the concept; however, most of them agree that it refers to the provision or receipt of information relating to a specific organizational task (Argote, 2012; Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). Others say it refers to the sharing of information relating to organizational expertise, or the generation and use of feedback pertaining to a specific product or service (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012).

Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) say that companies, which have managed to narrow their knowledge gaps are able to deliver superior value to their customers, while those that are unable to do so constantly have to recruit and train new talents – a process which leads to significant cost increments, lack of innovation, and poor service delivery. Thus, the ability of organizations to thrive in the wake of a highly competitive “knowledge industry” comes from their ability to use traditional resources in new ways (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Relative to this discussion, knowledge resources empower organizations to boost their key competencies in ways that they would otherwise be unable to, had they lost the vital resource. The same knowledge reservoir allows them to improve their competitive position in the marketplace by maximizing the value of their resources. Based on these discussions, the management of an organization’s intellectual capital is largely intended to improve its competitive position. Such an advantage would enhance an organization’s strategic position and maximize its resource capabilities as well (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

The need for intellectual capital management, as a key organizational process, partly comes from the understanding that in today’s information-centered and global economy, traditional factors of production are equally important as what employees know (Argote, 2012; Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). In other words, resource capabilities should be understood to have the same power as knowledge capabilities. Thus, prosperous companies in the 21st century are not only those which have the best access to land, factories and similar resources, but also those that are able to organize their knowledge management systems effectively.

Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) support this fact by saying that some organizations have failed to attain their goals not because of their inability to access natural resources, but because of their inability to acquire, organize and transfer knowledge. Furthermore, based on the same assessment, it has been established that most companies, which are successful at managing their knowledge platforms have a higher probability of outwitting their competitors through the adoption of superior operational practices (Meier-Comte, 2012). This statement is further augured with the success of some organizations, which have adopted total quality management (TQM) concept, which postulates that all employees of an organization should always maintain a high standard of operation for their activities. TQM is often safeguarded through succinct knowledge management processes that sometimes involve sharing the same resource. Collective learning processes and system engineering techniques are also aimed at improving organizational activities because they are often hinged on knowledge-based resource systems that generate enviable competitive advantages for companies (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). However, it is equally important to point out that some firms prefer to use centralized knowledge management systems as opposed to shared ones. For example, those that are associated with sensitive matters prefer this system to the shared one.

There are different types of knowledge shared across various organizational platforms. However, as Fawzy (2013) points out, the information shared is either explicit or tactical. Regardless of the typologies mentioned, managers are starting to acknowledge the need for knowledge sharing as a key organizational process because they say it is critical in transforming individual data into organizational resources (Fawzy, 2013). This fact is supported by several studies, which show that knowledge sharing leads to intellectual capital creation and idea generation (innovation) (Fawzy, 2013; Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). Other studies have shown that it leads to improved problem solving (Argote, 2012; Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). These findings have prompted many observers to contend that the process of sharing intellectual capital resources is a key ingredient in achieving innovation within different organizational departments (Fawzy, 2013). Other studies have associated it with team creativity and ultimately, improved organizational performance (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015).

Managing an organization that has different groups of employees may lead to conflicts and disagreements that would eventually hinder organizational productivity. In some firms, knowledge gaps are linked with knowledge-based complexities that hinder the decision-making process, making it slower and inefficient (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013). However, in others, there is a conscious decision not to share information because of the nature of operations, or any other issue relating to their performance. For example, knowledge gaps in the army are deliberately created. Therefore, discretion is often applied when managing knowledge in such contexts. It is also common to find these kinds of problems occurring simultaneously in environments characterized by significant knowledge gaps.

In extreme situations, this problem could lead to the failure of organizations to distinguish between interpretive failures and information shortcomings associated with decision-making procedures and company processes (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Here, knowledge sharing emerges as a dynamic process that requires vibrant interactions among different cadres of employees. Based on this understanding, it is important to understand the main drivers of this process and the influence of micro-level constructs of intellectual knowledge resource management on organizational outcomes.

The focus on micro-level constructs of knowledge management is deliberately selected as the premise for this paper because past research studies have often concentrated on macro-level constructs, such as dynamic capabilities and absorptive capacities, when investigating knowledge management. These macro-level attributes are often executed at a firm level and could be argued to be “out-of-touch” with some subtle aspects of operational performance, such as how employees interact with each other. Indeed, it is further argued by some observers that macro-level constructs are not firmly entrenched in micro-foundations of knowledge management (Francesca, 2017).

As mentioned earlier, micro-level foundations largely refer to the actions and interactions among individuals in an organization. They may include team-building efforts, the nature of employee relations with their supervisors, decision-making procedures, and worker appraisal processes among others (Francesca, 2017). These micro-level processes often underpin the knowledge management process. The failure of past researchers to pay attention to this important area of study in knowledge management has led many of them to question their origins and foundations. Therefore, the focus on micro-level constructs for understanding knowledge management is a different approach for investigating knowledge sharing and outlines the basis for which this study is premised on. Based on the understanding that micro-level constructs of knowledge management place workers at the center of knowledge management, differences between unique cadres of workers become central to understanding how knowledge is shared.

One of the most notable challenge organizations experience today when trying to understand knowledge sharing is comprehending the knowledge gap that exists between older and younger employees (Saleh, 2012). These two groups of workers denote the differences in intellectual capital between different generational cohorts. Indeed, researchers have observed that the seamless transfer of knowledge between different generations of workers is important in the realization of organizational success (Saleh, 2012). Pieces of evidence that support the above assertion point out to the possibility of cross-generational conflicts that could limit knowledge transfer (Shaw, 2013). Such conflicts could emerge from differences in beliefs, values, and attitudes about life (between the young and the old) that could ultimately influence how they carry out their work, or interact.

Indeed, although many organizations spend a lot of time and resources in trying to realize diversity within their workforce, with most attempts (at fostering diversity) being focused on realizing ethnic and gender differences, generational diversity has been relatively unexplored. Indeed, as Shaw (2013) points out, most organizations are struggling to balance the different needs and working styles associated with varied cohorts of employees. Contrary to the general expectation that managers should try to align the needs of these groups of employees with an organization’s needs, most of them have left workers to figure out this problem by themselves. Although most observers regard differences in inter-generational styles as a serious issue, they tend to hinder team performance, thereby leading to frustration, conflict and poor performance (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013).

Underlying the problem is a general understanding of how younger and older employees think. Many studies have tried to investigate these differences with three main ideologies representing groups of workers dominating most literatures. The first group of workers is the baby boomer population, which includes employees who were born between 1946 and 1964 (Acton, 2012). This population is often pitted against generation X, which is comprised of employees who were born in the 1965s and 1980s. The last group of workers is the millennials (or generation Y), which is comprised of employees born between 1980 and 1999. Research has pointed out that these groups of employees have different work practices that could be analyzed differently, based on their views, beliefs and values about work (Liebowitz & Frank, 2016).

Although the differences among these groups of workers will be further explored in the next chapter, Saleh (2012) says one argument touted by the “baby boomer” population against “Generation X” is the failure of the latter to use time-tested strategies because of their perceived lack of patience. Another belief about “Generation X,” cited in some literatures, is that they are often self-absorbed and too “spoilt” to appreciate what is around them (Liebowitz & Frank, 2016). Comparatively, the “Generation X” see the “Baby boomers” as being too rigid to change (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013). In other words, some of them say that the latter are “out of touch” with reality, because they are set in their ways too much to notice that they could do things in a better and more efficient way (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013).

An abundance of evidence shows how different generational cohorts have varied experiences and knowledge about organizational processes (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013). These knowledge gaps are detrimental to organizational sustainability because they could cause several problems, such as poor communication between different levels of employees and poor work coordination (just to mention a few) (Saleh, 2012; Shaw, 2013). These problems often arise because of divergent views and intellectual misinterpretations that could occur when different cadres of employees analyze the same sources of information (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

This study takes a keen look at how individual factors influence knowledge sharing in one organization – Saudi Aramco. Saudi Aramco is an energy company in Saudi Arabia. Its operations are mostly concentrated in the energy sector, with some literatures showing that its key focus is in the petroleum industry (IBP, Inc., 2015). A few of the main initiatives of the firm include optimizing the organization’s processes, building its capabilities, growing the business, and engaging the kingdom (Saudi Aramco Inc., 2015). Saudi Aramco has not had a long history of knowledge management; in fact, it only recently adopted the operational excellence management system in 2013 (Saudi Aramco Inc., 2015). After this process, all subsidiaries of the organization are supposed to operate under this banner. The company specifically operates operational excellence 12.7, which relates directly to knowledge transfer (IBP, Inc., 2015). However, this platform has not solved the knowledge gap problem between the young and older workers. This is an issue for the organization because it seeks continuity for all its workers. Details about this problem are explained in the section below.

Research Problem

After the Second World War, oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia. At the time, an American company known as Chevron dominated the global oil exploration business (OBG, 2013). This company partnered with Texaco to form what is known today as Saudi Aramco (OBG, 2013). The company’s name was simply an acronym for the Arabian American Oil Corporation. When there was a global trend to nationalize companies in the 1980s, the Saudi Arabian government bought the company’s assets and eventually controlled its majority shares (OBG, 2013). However, most of the organization’s employees were maintained from the traditional organizational structure (OBG, 2013). For more than three decades, there has not been any substantial change of key workers in the organization. This is a problem because most of the original employees are due for retirement. Based on this issue, Saudi Aramco, has experienced many challenges in its operations, including (but not limited to) poor trust in business, sustainability challenges, corporate brand and reputation issues, geopolitical/economic risk management, customer relation problems, inadequate innovation, operational excellence challenges and human capital problems (Saudi Aramco Inc., 2015).

Although the aforementioned factors affect the company’s operations, human capital problems emerge as the top concern for the firm because there is a growing body of ageing workers who do not interact openly with their younger counterparts (OBG, 2013). This concern has inhibited the realization of one of the main objectives of Saudi Aramco, which is to develop a reliable workforce that could meet the evolving technical and technological needs of its petroleum engineering processes (OBG, 2013). This is also a problem shared by most petroleum and gas companies in the kingdom because the Saudi Arabia Oil and Gas (2017) says many of such firms experience a looming problem in their human resource strategies because they lose well-trained, technically experienced, and skilled personnel because of retirement.

Many employees who work in Saudi Aramco were employed after a successful hiring campaign in the 1980s that saw many of them secure lucrative employment opportunities in the organization when the prices of oil was high (USA International Business Publications, 2015). The impending retirement of most of these workers from the workforce has made it imperative to develop a knowledge transfer program that would see older workers transfer useful technical information to the younger workers.

The knowledge gap present at Saudi Aramco is mostly characterized by the presence of a significant knowledge gap between employees who have worked for more than 23 years and those who have worked for less than a decade. Those who have worked for more than 23 years have a significantly higher level of knowledge compared to those who have worked for less than ten years.

The main problem experienced at Saudi Aramco is the lack of a knowledge transfer mechanism that would allow the organization to function properly in the event that many of its experienced employees retire at once. This issue could be problematic for the organization because it would signify a loss in knowledge that could impede the organization’s operations (OBG, 2013). This issue highlights the need for the oil company to preserve the intellectual capital resources of the organization because its operational practices require technical expertise that rests with those who have worked in the organization for a long time.

Underlying this problem is the risk that most employees who will leave the organization will take vital knowledge with them (USA International Business Publications, 2015). This risk could come at a huge cost to the firm because it has spent a lot of time and resources nurturing and teaching existing employees how to conduct critical knowledge processes in the company. To meet the challenges that bedevil the organization, there needs to be a sound plan of knowledge transfer between older and younger workers.

Purpose of Research

This study is designed to understand the predictors of knowledge sharing in Saudi Aramco and to emphasize the relevance of knowledge sharing across different employee groups that work in the oil company. Indeed, knowledge sharing could happen across different employee groups that could be divided along team lines, age differences, roles, responsibilities and other measures of organizational functions. The focus of this study will solely be on intra-organizational knowledge sharing and will emphasize on understanding the individual factors that influence knowledge sharing in the organization. This study would also strive to understand the level of employee satisfaction regarding the quality and quantity of information being transferred from older employees to the younger ones. Getting such information from workers could allow the organization to improve its formal knowledge transfer programs, such as the virtual reality tool, which allows younger workers to learn and understand the company’s plants (Saudi Aramco Oil Co., 2017).

Importance of Study

As mentioned in this paper, knowledge is increasingly emerging as an important resource for most organizations. In fact, some of the research studies reviewed in this document show that it constitutes among the most critical tools for improving an organization’s competitive advantage (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017; Argote, 2012; Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). Although its importance is rarely disputed, unless knowledge is shared freely among employees, organizations would be limited by their inability to exploit their potential for maximizing their intellectual capital. Of particular importance to this study is the need to understand how knowledge is shared across different generational cohorts at Saudi Aramco. This view is vital to the sustainability of the company because older employees are supposed to share their intellectual resources with their younger counterparts.

This study would take a keen look at how individual factors influence knowledge sharing in the organization. The individual factors include willingness to share information, motivation to share data, the quality of knowledge people are willing to share, and the level of collaboration people foster when doing so. Part of the study would also seek to understand the perceptions of the quality and quantity of information shared across cross-generational relationships. Therefore, the study would help in preserving the institutional memory of long-term employees and help transfer the same knowledge to newer workers. This analysis would help Saudi Aramco to store or preserve the knowledge held by their most experienced employees before they leave the organization.

The need to fill the knowledge gap in the Saudi-based oil company has been supported by many researchers, such as Francesca (2017), who say that the failure to do so is akin to dismantling an organization’s knowledge and intellectual assets. Here, knowledge is not conceived to be a product that could be packed and distributed, but a resource that should be shared. The transfer of current knowledge to new employees and the process of generating new ones are derived from the interaction between older and younger workers in the organization. If left unaddressed, the differences between both sets of employees could significantly affect how the organization operates (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Concisely, similar to how organizations have improved ethnic and gender diversity in their workplaces to increase their productivity, filling the gap that exists between the aforementioned groups of employees could yield the same outcomes.

Research Statement

The aim of this research is to bridge the knowledge gap at Saudi Aramco. The research goals are as described below.

Research Goals

- To provide an inventory and catalogue of Saudi Aramco’s critical activities

- To determine the risk of loss of critical knowledge, skills and behaviors at Saudi Aramco

- To prepare Saudi Aramco to minimize its knowledge gaps

- To establish knowledge transfer relationships between knowledge providers and knowledge recipients at Saudi Aramco

- To develop knowledge transfer plans for identifying at risk knowledge at Saudi Aramco

The aforementioned goals are attached to specific objectives, which are to be pursued in the study. The objectives appear below.

Research Objectives

- To identify at-risk critical activities (knowledge)

- To identify employees who have knowledge and experience of value (knowledge providers)

- To transfer knowledge as efficiently and as effectively as possible to those who need it (knowledge recipients)

Guiding the research will be a set of questions that appear below.

Research Questions

- What are Saudi Aramco’s critical activities?

- Which employees of Saudi Aramco have the knowledge and experience of value?

- What is the nature of knowledge transfer relationships between knowledge providers and knowledge recipients at Saudi Aramco?

- How could Saudi Aramco bridge the knowledge gap between the older and younger employees?

Research Hypotheses

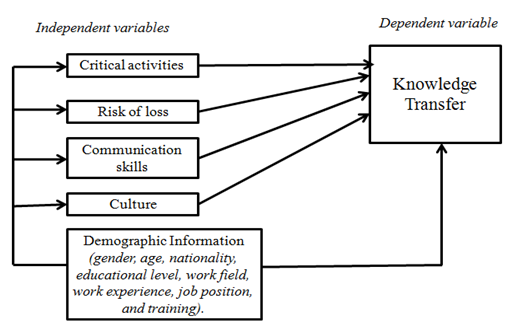

- H1: Critical activities have an effect on knowledge transfer.

Ho: Critical activities do not affect knowledge transfer

- H2: Risk of loss has an effect on knowledge transfer.

Ho: Risk of loss has no effect on knowledge transfer

- H3: Communication skills have an effect on knowledge transfer.

Ho: Communication skills have no effect on knowledge transfer

- H4: Culture has an effect on knowledge transfer.

Ho: Culture has no effect on knowledge transfer

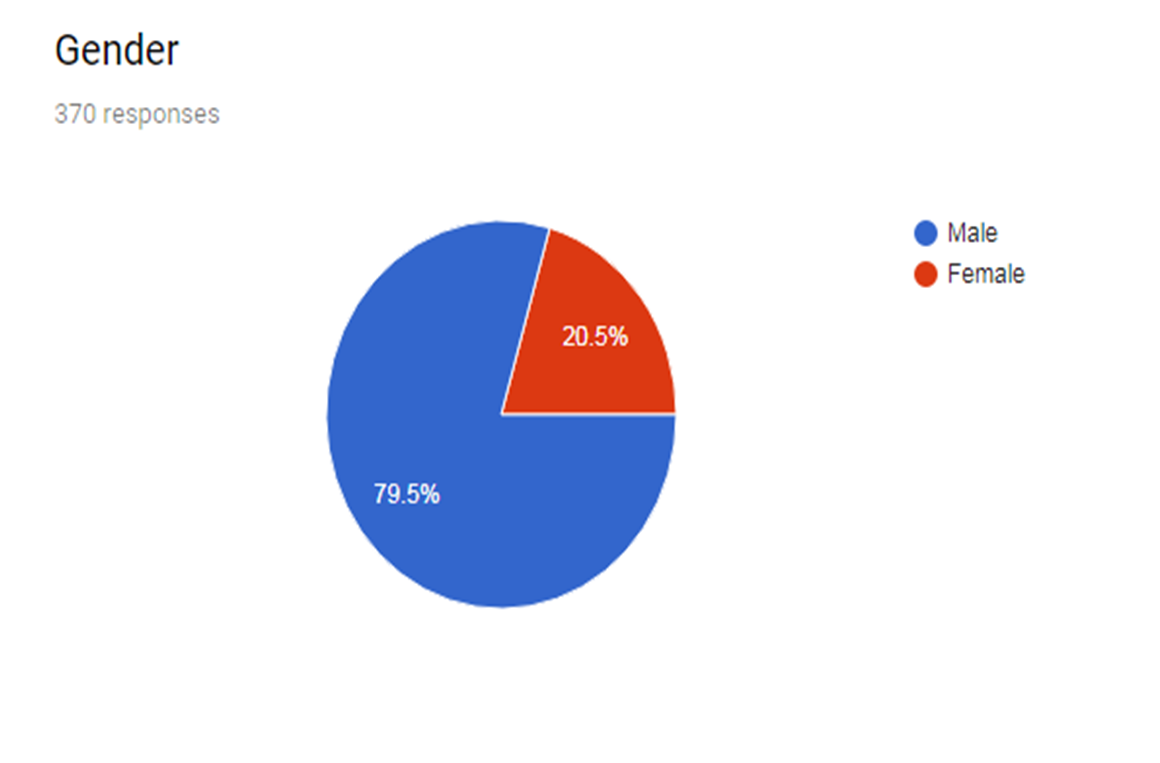

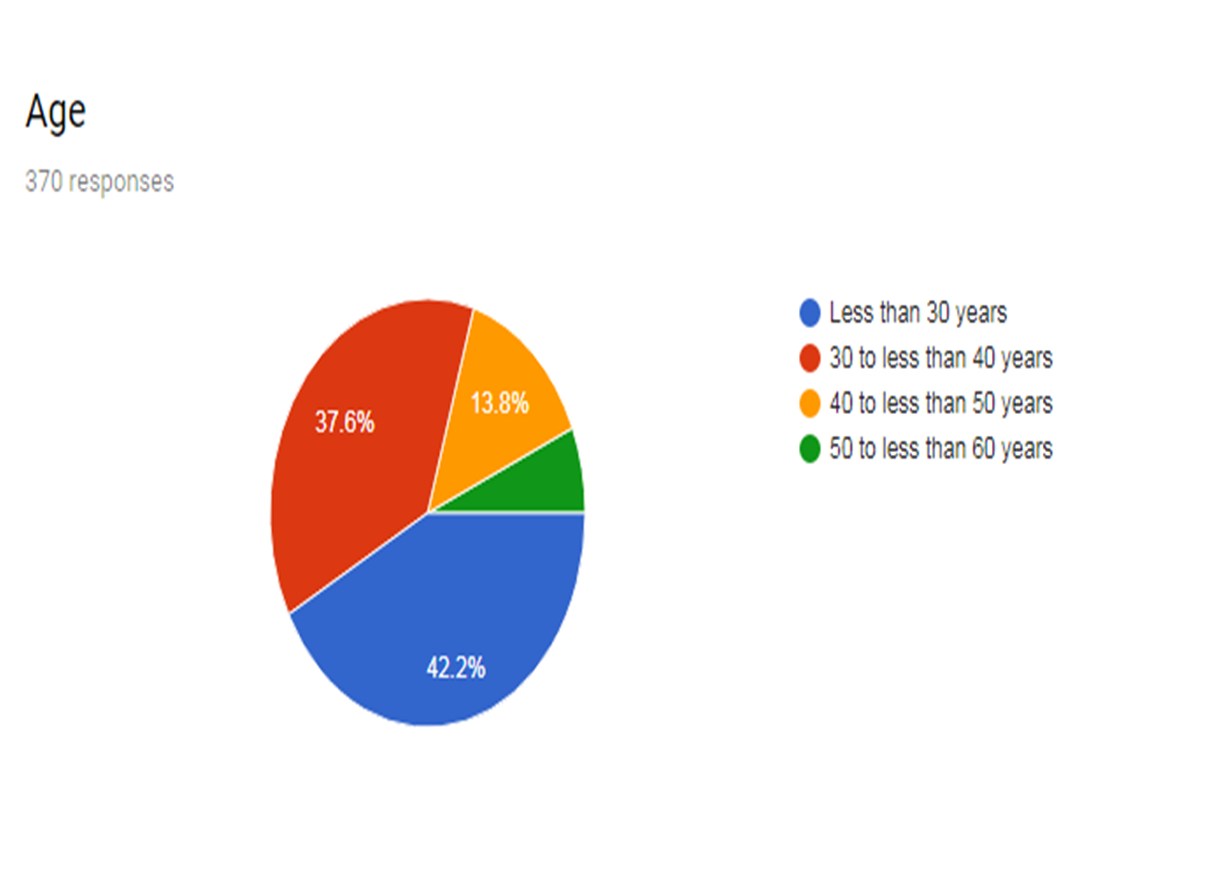

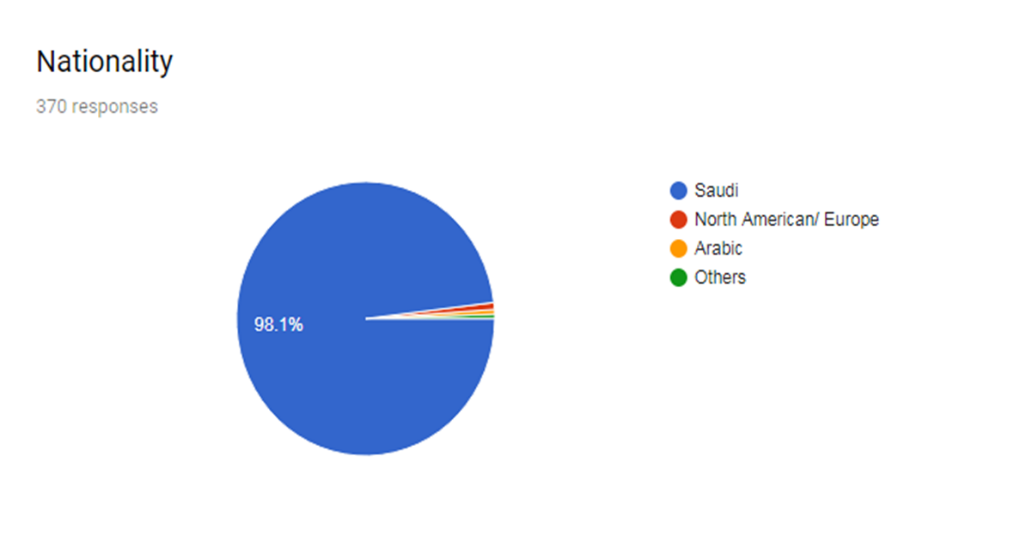

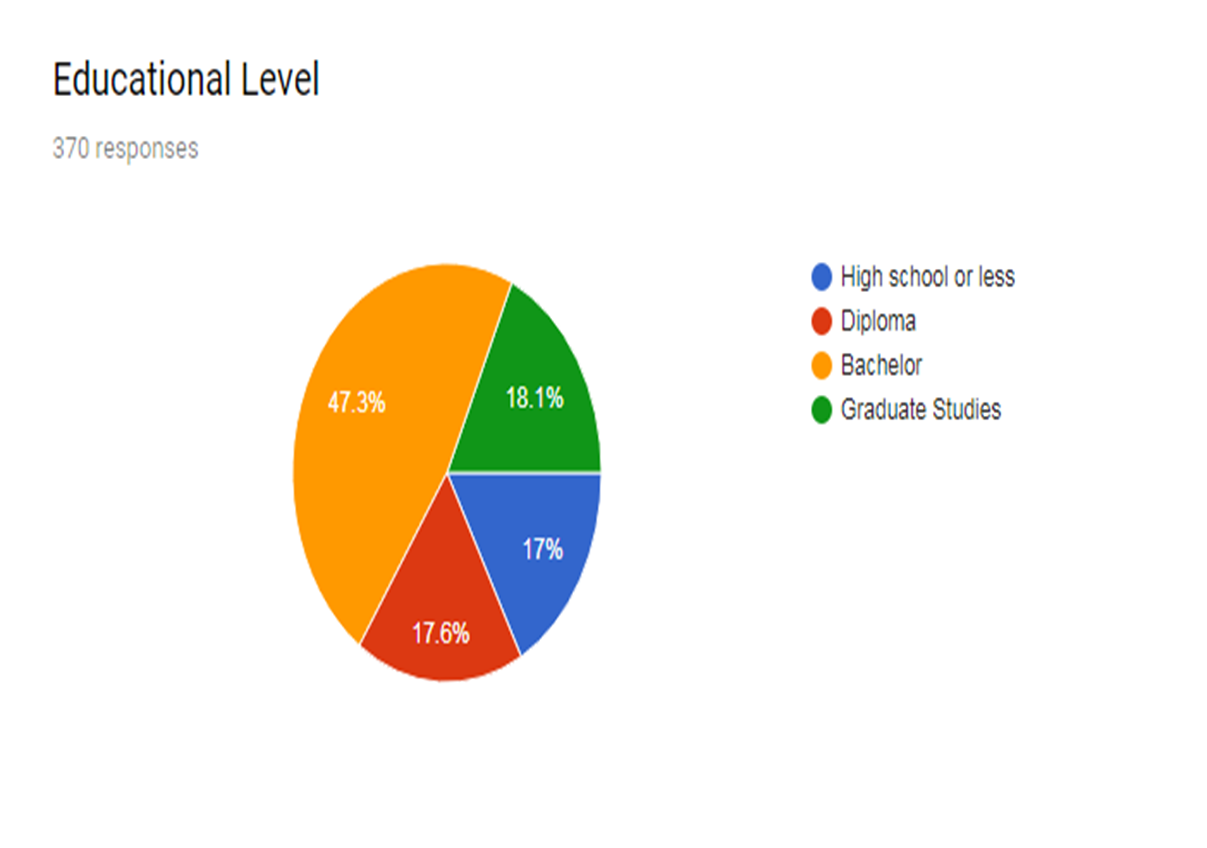

- H5: The demographic information (gender, age, nationality, educational level, work field, work experience, job position, and training) have statistically significant differences on Knowledge Transfer.

Ho: The demographic information has no effect on knowledge transfer

Expected Outcomes

The expected outcomes of the research are as follows:

- To create a cost-effective process to develop and retain talent at Saudi Aramco

- To preserve the institutional memory of long-time employees and transfer that knowledge to younger workers

- To store and transfer the lessons learned from experienced workers before they leave employment

Dimensions That Would Be Explored In the Research (Scope of Research)

Some key dimensions of knowledge management that would be explored in this study include the nature of relationships between older workers and newer employees at Saudi Aramco, knowledge transfer structures in the organization, and critical activities that are susceptible to the loss of vital knowledge in the company. These dimensions of research will address the main tenets of intellectual capital resource management in the organization, as proposed by Argote (2012).

This study will be different from many others that have investigated knowledge sharing in organizations because the above dimensions of study focus on micro-level constructs of the same issue, as opposed to macro-level constructs which have been highlighted in other studies. Four micro-level constructs will guide the researcher – willingness to share information, communication structures for sharing information, motivation to share data, and collaboration among employees when sharing knowledge. These four concepts of individual interactions define the scope of this study because they are the main catalysts of knowledge sharing in organizations (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). The scope of this study would also be limited to intergenerational knowledge transfer in one organization – Saudi Aramco.

Significance of the Research

The findings of this study will be important to the prosperity of Saudi Aramco because they could create an emphasis on employee development in the organization. Similarly, the knowledge that will be derived from this study will be instrumental in creating cost-effective processes to develop or retain talent. This way, Saudi Aramco will be better placed to preserve its institutional memory. At the same time, it will be in a position to transfer the same knowledge to newer workers effectively. Thus, it would be possible for the company to store and transfer the knowledge held by their most experienced employees before they leave the organization.

The findings of this study will not only be useful in minimizing the knowledge gap that exists in the organization, but also align individual and company goals. This way, there will be a greater focus on job-specific development and a preservation of the critical knowledge present in the organizations. Moreover, through the process, there would be a greater facilitation of efficient and effective job-specific development in the firm.

By adopting some of the recommendations outlined in this study, Saudi Aramco could also meet its short-term and long-term goals. The short-term goals include an improvement in the speed and ease through which it could undertake knowledge transfer, and an increased level of efficiency for improving existing communication styles and network operations. Other short-term goals that could be experienced by the company include improving work effectiveness in the organization (such as improved problem solving), encouraging more innovative and out-of-the-box thinking and the prevention of a “re-invention of the wheel” because younger employees would be learning from the older ones. Some long–term goals that could be enjoyed by the organization include inculcating knowledge transfer in the company’s culture and allowing knowledge management to constitute an organization’s key functions.

Definition of Terms and Key Concepts

- Knowledge – employee skills and experiences

- Knowledge Gap – The difference between what an organization can do and what it is required to do, relative to knowledge management

- Knowledge Management – The art of managing knowledge

- Knowledge Transfer – The art of exchanging knowledge among different groups of workers

- Generational Cohort – A group of workers defined by an age group

- Intellectual Capital – The intangible operational resources of an organization

Literature Review

This chapter contains a review of what other researchers have written about the research issue. In this section of the document, evidence would be provided to show how specific theories and models of knowledge management apply to the research topic and how they align with the research goals. The conceptual framework of these discussions appears below.

Conceptual Framework

Recent studies have departed from the conventional definitions of knowledge and focused on the relational nature of the concept. According to the latter view, knowledge should not only be transferred from a selected group of employees to another, but also be used to create value in an organization (Jasimuddin, 2012). In this regard, intellectual capital management emerges as a process of wanting to know more (Jasimuddin, 2012). This reasoning is regarded as the occupational community perspective and has been widely used in understanding the social and situational context of knowledge management (Abbott, 2016; King & Lawley, 2016). Within the same framework, social interaction within communities could be widely perceived as the main context, or platform, through which knowledge sharing takes place.

The occupational community perspective does not only regard intellectual capital management as a process that occurs at a social and actionable level, but also at a personal level. The focus on the micro-level interactions gives us an in-depth insight into the knowledge processes that characterize the relationships people or organizations build within this system. As Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) observe, the focus on alliance building as a unique level of knowledge management system tends to focus on knowledge management at organizational levels. Nonetheless, this analysis has also included the role of interpersonal relationships within the wider structure of knowledge management. While different studies have shown that knowledge management occurs at organizational levels, knowledge sharing tends to be more profound at an interpersonal level (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Haider and Mariotti (2017) support this assertion by saying that informal contacts were instrumental in gaining access to information that would otherwise not be available in the public domain. Haider and Mariotti (2017) also add that the exchange of information across different organizations mostly occurs through informal contacts.

The conceptual framework for this study will be based on the processual approach of knowledge management to understand how to fill knowledge gaps between different groups of employees. Jasimuddin (2012) defines process as that which involves the spread of information sharing activities over a specific period. Abbott (2016) takes a different stand on the issue and says that process refers to a specific focus on complex organizational activities that occur over a specific time. Organizational phenomena categorized this way include (but are not limited to) cultural exchanges, decision-making processes, and structural change processes (Jasimuddin, 2012). Many research studies have evaluated this conceptual framework by paying a close attention to the nature of interactions among different stakeholders as a measure of how they exchange knowledge and interact with each other (Abbott, 2016; King & Lawley, 2016). Although many processual analyses use time as the main unit of analysis, the process does not only stop at this point of analysis; instead, it extends to the conceptualization, analysis, and description of events or activities in an organization that fall within the context of knowledge management. The basic nature of the processual approach of knowledge management is the understanding that social interactions and knowledge management often occur across a specified time. Here, the period taken for knowledge exchange to occur and context, which this process occurs, are at the center of all social interactions that lead to knowledge exchanges (King & Lawley, 2016). The uniqueness of this approach is temporality, which makes it unique from other frameworks of analysis.

The driving assumption behind this conceptual framework is the understanding that social interactions often occur dynamically and not necessarily in a steady manner. From an organizational perspective, this conceptual framework recognizes the duality of agency and context when investigating knowledge transfer issues. This analysis shows that contexts have always shaped the nature of knowledge transfer, while actors are often producers of the same process. This same analysis shows that actions are the main drivers of the processes that lead to knowledge exchange. However, at the same time, the entire chain cannot only be explained by the actions of one individual. Within this analysis, people’s actions are viewed within varied, but specific, contexts that ultimately limit the kinds of information that could be exchanged. The insight and influence of information processing are also limited by the same context. The social interaction that occurs between agents and their operational context is often analyzed through a cumulative process. Although the field of processual analysis is still young and the boundaries of analysis not clearly defined, the case study approach has been commonly accepted in current research analysis because it focuses on issues and events that are integral to the understanding of a research phenomenon. This approach is also adopted in this study.

What Is Knowledge?

The historical understanding of knowledge is shaped by the work of different scholars, poets, and academicians. For example, Ferdowsi and Francis Bacon, who are well-known poets, have explained knowledge in artistic contexts, such as poems, songs and other diverse literary works (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Some literatures also point out that there was a time people were often defined by the kind of knowledge they had (Schiedat, 2012; Ray, 2013). Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) investigated the concept of knowledge and said that it has undergone a metamorphosis that is characterized by three evolutionary phases.

The first phase is one that took place before 1700 A.D. During this period, there was a general attitude among managers that meant that knowledge should be substituted for wisdom and enlightenment should be pursued at all times (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). The second phase occurred between 1700 and 1800 A.D (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). This era heralded a period where technology was pursued as the main basis of knowledge creation. This phase also heralded a stage in knowledge development where there was the systematic organization of knowledge and a resurge in the importance of setting goals to guide the process (Schiedat, 2012; Ray, 2013). The third phase of understanding knowledge happened in 1800 A.D where some researchers used scientific management principles to improve the discipline (Schiedat, 2012; Ray, 2013). These principles were meant to consolidate employee skills and experiences.

Before the post-modernist era of managing intellectual capital, managing knowledge was a concept mainly sourced from the tangible assets of an organization, such as cars, inventory, machinery and equipment (just to mention a few) (Schiedat, 2012). Most researchers termed these sources, associated with the generation of intellectual capital, as having structure and tangibility. They were also synonymously referred to as hard capital (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). However, in today’s economy, the intangibility of a resource is as important as the need for having tangible resources (Ivey, 2014). Such intangible resources include organizational culture, process systems, effective teamwork, and innovative networks (Ivey, 2014). Nonetheless, researchers agree that the concept of knowledge management stems from three key resources. The first one is religion and philosophy, which helps to comprehend the nature and role of knowledge. The second origin of the concept comes from psychology, which has helped to understand the role of knowledge in organizational behavior. The third root of the concept is economics and social sciences, which have helped researchers to understand the role of knowledge in the workplace (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

Types of Knowledge

There are two main types of knowledge highlighted by several research studies, which have explored knowledge gaps in organizations – explicit and tacit knowledge. They are discussed below:

Explicit Knowledge: Explicit knowledge is both qualitative and quantitative, in the sense that it can be described both numerically and using words. Explicit knowledge can also be easily shared across several platforms and in different forms, including files and videos (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017; Argote, 2012).

Tacit Knowledge: Tacit knowledge differs from explicit knowledge because information is often acquired through employee experiences. Such information is often not freely available for transfer because it is still held by individuals and has not been recorded or documented. Some forms of tacit knowledge that could manifest in organizations include information that is obtained from having good competence, decision-making skills, work ethics, social networks, and values (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017; Argote, 2012).

Knowledge Management Gaps

According to Allen and Beech (2013), knowledge gaps refer to “demarcate absences” (p. 56). Generally, they yield to adverse organizational outcomes, which signal a weakness on the part of the knowers and, by extension, a lack of ideas, practices and networks within an organization that lead to the negative outcomes in the first place. Since ideas, practices and knowledge are among the main constituents of an effective knowledge system, the lack of these attributes means certain domains would be inaccessible. The actor-network theory affirms this assertion through a statement shared by Allen and Beech (2013) which says, “Knowledge gaps are domains unpopulated by different actors, where enrollment becomes a practical impossibility because there is nothing or no one to enroll” (p. 13). The social network theory is also applicable here because it shows that knowledge gaps are symbols of structural holes in the organization (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). In other words, they delineate paths of greatest resistance and by virtue of doing so; they divert an organization’s resources to paths that have the least resistance. This statement means that institutional arrangements are reinforced and the status quo prevails, or questions about what could be of an organization left unanswered. Based on this assertion, knowledge gaps emerge as latent structures of different organizations. On one hand, they facilitate knowledge exchange in specific company domains and on the other hand, they foreclose possibilities in other organizations (Allen & Beech, 2013).

Based on the above assertions, knowledge gaps appear as social products that have a profound social effect on the society. In principle, both of these effects are measurable and identifiable. Nonetheless, as Allen and Beech (2013) point out, knowledge gaps are also social processes. In other words, they are shaped by human practices and interactions. Organizational practices and institutional pressures also affect the same gaps. Although these elements are variable, they are not evenly distributed in different social contexts. Therefore, in addition to describing the social features of these knowledge gaps, as highlighted by the social exchange theory, it is equally important to explain their distribution across knowledge systems, relative to the processes that lead to their creation.

Generally, knowledge management gaps often exist when there is a difference between what organizations can do and what knowledge management systems help them to achieve. Different studies have come up to explain the concept. The most notable one is by Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017), which defines the knowledge gap as what a company should do and can do with respect to knowledge management.

Some studies point out that the main types of knowledge gaps are socioeconomic and socio-specific. Tofanelli (2012) says some of the intellectual capital gaps seen in today’s organizations result from infrastructural gaps. Additionally, he says that the main effect of these infrastructural gaps is the inability for organizations to develop effective systems for managing knowledge (Tofanelli, 2012). King and Lawley (2016) add to this conversation by saying that knowledge gaps often suffice when organizations do not understand how to bridge the gap that exists between the processing and demand for current knowledge. Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) also adopt the same approach by saying that this gap exists as the qualitative and quantitative difference between existing and required knowledge.

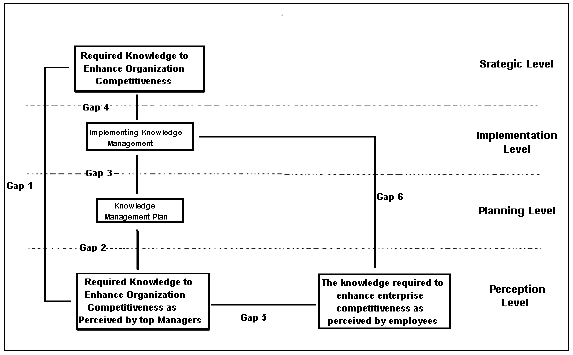

Although the above-mentioned researchers have different conceptualizations of what knowledge gaps entail, they generally agree that the gaps stem from four areas of operational management – strategy, planning, implementation, and perception. Cumulatively, the researchers point out that the failure to recognize these knowledge gaps could have significant consequences for organizations because they would be engaging in a process that is flawed, relative to the problems they will experience in the implementation stage (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Therefore, it is important to engage in different knowledge management processes, such as a requirement analysis and a risk management process, before designing or implementing knowledge management systems.

Types of Knowledge Gaps

Discussions about existing types of knowledge gaps have arisen from studies that have tried to explain how employees interact with one another (socially) to acquire new knowledge or retain existing ones. Nonetheless, it is important to understand these intellectual capital gaps because studies have shown that they are vital to the sustainability of organizations (King & Lawley, 2016; Tofanelli, 2012). A study done by Kriesi (2012) to identify the main types of intellectual capital gaps through a succinct processual review, established that there were five main types of knowledge gaps. These gaps address different intellectual capital management requirements that are central to this analysis. They are further explored below.

Physical Capital Knowledge Gaps:Physical capital gaps stem from knowledge types that are related to managing capital resources, such as the traditional factors of capital (Kriesi, 2012). Within this analytical scope, Kriesi (2012) says this knowledge gap could occur if some employees do not understand how to operate machinery, how to draw operational plans, or how to make use of existing tests required in their operational plans.

Intellectual Capital Knowledge Gaps: This category of knowledge gap refers to organizational skills that are needed to implement specific aspects of a company’s management strategy (Kriesi, 2012). Handzic and Bassi (2017) add that this type of gap emerges when there is a lack of operational skills to support management expertise. Some aspects of organizational plans that could be affected by the lack of proper organizational skills include how to manage operations, how to make decisions, and how to solve problems (Handzic & Bassi, 2017). The most important aspect of intellectual capital knowledge gap is the realization that the knowledge gap exists in the first place (Kriesi, 2012).

Relationship Management Knowledge Gap: This type of knowledge gap often exists in organizations that are service-oriented because research shows that organizations that treat their customers poorly often suffer from this type of knowledge gap (Handzic & Bassi, 2017). Poor relationships within markets, contractors and subcontractors are also other symptoms of the existence of the knowledge gap. Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) add that this gap does not only affect how organizations maintain existing relationships with their clients, but also how they could forge new ones with others.

Social Capital Knowledge Gap: This type of knowledge gap often thrives when organizations do not have a proper understanding of how to develop trust or trustworthiness with their business partners or customers (Ngeloo, 2017). How organizations treat their partners, the kinds of roles and responsibilities they assign them and the kind of independence they give them to carry out these duties partly contribute to the creation of these knowledge gaps (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Based on the key areas which this knowledge gap affects, organizations which tend to rely on successful partnerships for their success tend to be most affected (Ngeloo, 2017). One interesting angle to this analysis is that the knowledge gap also relates to the need for organizations to manage their intellectual capital management challenges by understanding their localized employee relationships. Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) have also included this gap in their research by saying that organizations often learn from their experiences with other organizations when forging new relationships with others. This way, the social capital gap decreases.

Cultural Gap: As its name suggests, the cultural gap often arises when organizations fail to understand how to navigate through a multicultural business environment (Meier-Comte, 2012). In this regard, there is a problem associated with the improvement of work practices, especially in environments where organizations want to change their culture. This gap is likely to affect different management techniques applied in organizations, such as teamwork and problem solving initiatives. According to Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017), different organizations fill the above knowledge gaps by undertaking unique knowledge processes. Some of them include collaborating with other firms, improving internal knowledge management systems, and disseminating knowledge to concerned parties (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

Knowledge Gap Model

The knowledge gap model adds to our understanding of knowledge as a critical organizational resource. It presupposes that knowledge is a type of wealth, which is unevenly distributed among people of higher and lower socioeconomic status (Sloan, 2014). In other words, it argues that as information slowly diffuses to the society through different modes (such as mass media and word of mouth communication), people of higher socioeconomic status tend to acquire it faster than people of lower socioeconomic status do (Sloan, 2014). Thus, the knowledge gap between these two segments of the population tends to increase (Ray, 2013).

The same phenomenon also happens in organizations because studies show that cohorts of employees acquire and process knowledge differently (Ray, 2013). If we use the above example, we find that managers are the same as people of higher socioeconomic status who tend to acquire knowledge faster than people of lower socioeconomic status (who could be likened to lower level employee groups). This knowledge gap model was introduced in the 1970s, and it has been implicitly used throughout mass communication literature (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015).

In the mid-1970s, there were attempts aimed at refining this model because different researchers, such as Donohue, Tichenor, and Olien, were interested in understanding how to eliminate this knowledge gap, or even to attenuate it (Ray, 2013). To this extent of interest, they started investigating national data related to understanding how to weaken knowledge gaps. Their investigation pointed out that three ways could be used to eliminate the knowledge gap and they include an increased awareness of the intellectual capital gap, decreased levels of social conflict brought about by the issue, and the level of homogeneity in a community (Ray, 2013). From these findings came the developments of the knowledge transfer triad, which is comprised of three main actors – knowledge provider, knowledge recipient, and knowledge supervisor (Brčić & Mihelič, 2015). The knowledge supervisor is always at the center of the knowledge triad because he moderates the interaction between the knowledge provider and recipient. Knowledge is often shared among the three players.

Knowledge Management

Different scholars have described the process of managing knowledge as an initiative by organizations to create, protect and preserve their intellectual property. For example, Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) say knowledge management involves the creation of information pertaining to an organization with the goal of making it readily available to other employees in an organization. The same authors describe the same concept differently by saying knowledge management involves the design of organizational structures to effectively use its intellectual capital (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

The principle of knowledge management systems largely stems from the field of “undone science” (Allen & Beech, 2013). This conception situates the production of knowledge within three realms of analysis, which are found within the institutional matrix of the state, organization, and social movements. These social movements are often used by researchers to draw attention to the undeveloped areas of research, which strive to present knowledge gaps as a tenet of “undone science.”

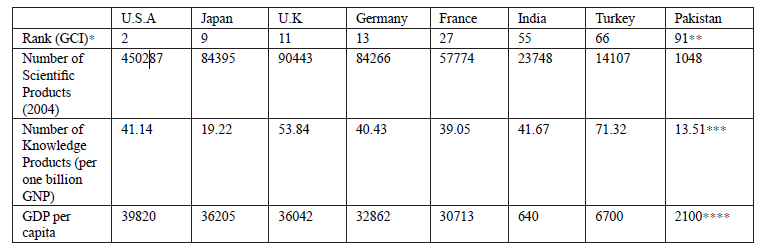

Researchers have pointed out that effective intellectual capital management is not only useful in creating a competitive advantage among organizations, but also in creating a competitive advantage among different countries (Ray, 2013). The opposite is also true because nations that often suffer from lower levels of economic, social, and political development standards often suffer from poor knowledge management standards (Ray, 2013). Figure 2.1 below affirms this situation because it shows that the most developed countries often have a high number of knowledge products.

The table above measured the development or advancement of different economies using the growth and development index, which is a measure of the economic macro-environment in different nations (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). How these countries undertake their public governance processes and their levels of technological development were also other measures involved in the analysis of national development. Similarly, total quality management was used as another index to predict the efficiency of how different countries managed their knowledge.

In the organizational context, the efficiency of knowledge management often increases when managers are experiencing the need to know their competitors’ actions and how they are formulating, designing or implementing their business strategies (Meier-Comte, 2012). Contextualized studies have shown the effect of knowledge management systems around the globe. For example, in Iran, researchers contended that the main problem associated with its organizations is a weak knowledge management system (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

They also argued that these problems have led to the failure of these organizations to manage their knowledge effectively and extract the most value from it (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Indeed, as Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) posit, organizations that fail to realize the importance of having this effective strategy for managing their knowledge suffer a high possibility of experiencing serious gaps, based on the creation of knowledge gaps that would occur from their inaction. Relative to this assertion, Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) add that such organizations could suffer different negative outcomes such as a decline in quality of operations, operational redundancies, and the occurrence of mistakes and errors in the provision of goods and services. The failure to develop proper knowledge management systems also creates the likelihood that an organization’s knowledge resource would be depleted and the time and money involved in creating it would go to waste.

Knowledge Management Approaches

As shown in this chapter, many literatures have highlighted the need for knowledge sharing, and emphasized its importance in the context of today’s complex, and dispersed knowledge environment. Edwards (2016) adds that, in today’s fast –paced society, it is difficult for organizations to rely on their internal competencies or knowledge. Thus, they need to forge alliances with other organizations to maintain their competencies (Edwards, 2016).

Researchers have pointed out that pools of information (or knowledge) often allow the participating organizations to improve their competencies, skills and strategies (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). Here, different studies point out that knowledge is not only accessed, but also internalized by organizations and stored to achieve the aforementioned goals (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). This process is multifaceted. Besides creating a common pool for accessing the knowledge, North and Kumta (2014) say that forging new alliances between companies could also help to foster the generation of new intellectual capital in them. While many studies often highlight the need for knowledge exchange to occur between knowledge providers and knowledge recipients, they may have as well presented knowledge as a tangible resource, such as land, because their analyses mirror this analogy (Francesca, 2017; Argote, 2012). These discussions have happened within the context of understanding knowledge management approaches.

Varied research studies show four types of knowledge management approaches. The first and second ones are the mechanistic and systematic approaches. The last two are the core competency and cultural approaches (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). They are discussed below.

Cultural Approach: The cultural approach to knowledge management traces its origins in the field of change management (Ivey, 2014). This approach looks at knowledge as a management issue. Although technological management is treated as a useful tool for managing this resource, proponents of the cultural approach do not view it as the only instrument for doing so. Instead, they focus more on innovation and creativity (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Thus, they do not necessarily believe in manipulating explicit resources to manage knowledge effectively.

Knowledge sharing often occurs within an institution or a company because these setups often accommodate employees who work together and share their experiences within the same settings (Ivey, 2014). As Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017) point out, such setups help organizations to share intelligence (freely) among their key employees. There are two key assumptions underlying the cultural approach. One of them is that organizations, which pursue them, are often willing to shake up their organizational cultures to improve employee behaviors. Another one is that organizational behaviors are often changed whenever businesses have exhausted the limits of their technological innovations (Meier-Comte, 2012).

Core Competency Approach: Proponents of the core competency approach say that effective knowledge management systems are often developed when intellectual capital is deemed as a key resource for organizational prosperity (Meier-Comte, 2012). However, in this context, it is pertinent to note a distinction between the ability of organizations to improve their performance and their ability to improve their knowledge management systems. This is not to deny their complementary nature because studies have also shown that they are critical tenets of organizational identities as well (Ivey, 2014). Generally, the core competency approach is a technique for using an organization’s vital knowledge to develop superior goods and services. These core competencies could also include the efficiency through which companies or organizations deliver goods or services to the market and the efficiency through which they do so as well (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). The same competencies allow organizations to develop customized goods/services and optimize their logistics, at the same time. The process of employing qualified employees and disseminating a succinct vision for the organization are also other attributes or organizational efficiency that are attributed to organizational success (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

The Systematic Approach: The systematic approach involves using predetermined systematic procedures to disseminate information among a selected group of employees. The goal of the systematic approach is to achieve desirable outcomes for an organization and not necessarily to certify or approve the processes involved. This approach comes from the philosophy that considers it impossible to retrieve value from a resource if it is not modeled well enough (Francesca, 2017). Part of this philosophy is reinforced by a belief that most knowledge resources could be explicitly modeled to provide value to organizations and that solutions could be easily found through such a process. Another assumption lies in the possibility of investigating the nature of knowledge management and solving associated problems by simply applying traditional methods of decision-making (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). Although cultural issues are critical in the same analysis, it is vital to appreciate the importance of systematic thinking. Therefore, while changes may occur among employees, organizational policies also need to support the same changes. One last assumption of this model is that technology is useful in solving knowledge management issues (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017).

The Mechanistic Approach: The mechanistic approach to knowledge management is enshrined in the philosophy that more could be done using appropriate tools or technology (Bharadwaj, 2015). In other words, more of the same could be done better than is currently done. Underlying this fact is the assumption that access to information is vital to the process of managing intellectual capital and enhances methods of accessing and using information in an organization (Bharadwaj, 2015).

Knowledge Management Models

According to Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017), two models generally represent knowledge management in organizations. They are described below.

First model: The first model highlights the difference in knowledge acquisition between people of a higher and lower socioeconomic status. The general understanding is that people who hail from a lower socioeconomic status often exhibit signs of a poor understanding of policy-relevant information (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). They also show signs of poorly understanding the importance of increasing public knowledge through mass media channels. Figure 2.2 below shows the model of knowledge management gap, as described by Simar and Rahmanseresht (2017).

Two types of explanations could apply to the aforementioned knowledge gap model. One of them is trans-situational, in the sense that the knowledge gap could be merely created from conditions associated with lower socioeconomic levels. One issue that could be associated with this analysis is the probable poor communication skills associated with people of lower socioeconomic status (Jasimuddin, 2012). A situation-specific theory has also been used to explain the same knowledge gap by demonstrating that the gap could exist if people of lower socioeconomic status do not understand the need to acquire incremental information because they deem it as irrelevant or non-functional to their lives (Jasimuddin, 2012). These two schools of thought have been historically used to explain people’s propensity to hold and seek information.

Second model: This model of knowledge management is hinged on establishing a chain of knowledge management. It has been systematically used to explain why some organizations experience management gaps when implementing knowledge management systems. These gaps have been explained in four ways, as described below:

- Strategic Perspective: The strategic perspective argues for the need for organizations (or managers) to scan their environments and seek opportunities for development, or improve their competitive advantages (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). The failure to do so creates gaps that explain why some of them are unable to keep up with their competition. These gaps are best explained by the difference in knowledge management and top management outcomes.

- Perception Perspectives: The perception perspective often points out the probability that top managers may fail to identify the knowledge required to improve their organizational competitiveness. In this regard, a gap forms between the structures present in an organization to manage its intellectual resources and the knowledge management structures that are actually desired (Birkman International, 2017). This difference may also emerge within an organization’s management structure because some employees may have different perceptions about what the organization needs to do, in terms of its knowledge management systems. The same variance may also emerge from the difference in the perception of managers and employees regarding the need to acquire, or retain, specific knowledge in the organization (Birkman International, 2017).

- Planning Perspective: Most managers often plan their organization’s processes, depending on how they understand the company’s internal and external environments. When these managers experience difficulties trying to apply the findings they get from this analysis to the organization, a knowledge management gap emerges (Simar & Rahmanseresht, 2017). The same is true if employees fail to translate this information into tangible value for the organization, especially when they fail to understand the importance of such an analysis.

- Implementation Perspective: It is vital for organizations to align their knowledge management systems with their goals. The failure to do so often results in knowledge management gaps. Within this understanding, it is essential for employees to gain the right perceptions and appreciate why such knowledge is good for the organization. Failure to do so would also create knowledge management gaps. Based on the two models defined above, we find that six knowledge gaps emerge. They are highlighted in table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1. Knowledge Gaps

Infrastructure Capabilities to Fill Knowledge Gaps

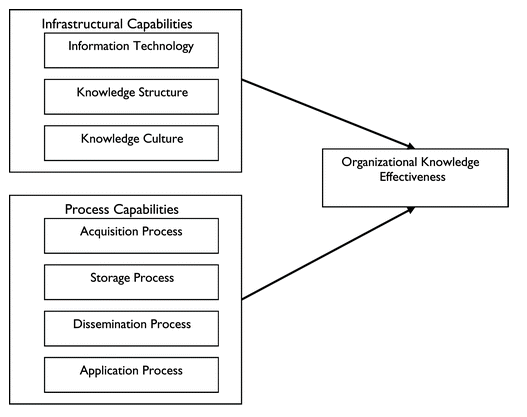

Filling the knowledge gaps that emerge in different organizations is an art that managers need to learn when designing a strong infrastructure to aid the process. There are three types of infrastructure commonly applied in knowledge management – information technology, knowledge structure, and knowledge culture. These elements of knowledge management interact through dynamic processes that include acquisition process, storage process, dissemination process, and application process. Both the infrastructural and process capabilities lead to organizational knowledge effectiveness. The elements interact as described in Figure 2.3 below.

Information technology: As shown from the diagram above, technology is a key infrastructural component of knowledge management. According to Bharadwaj (2015) technology is an important tool for mobilizing the social capital needed to make knowledge sharing systems work. This tool is superior to many others that will be discussed in this paper because it is able to transcend the barriers of space and time that often limit the other types of knowledge sharing platforms. Technology is also superior to other forms of knowledge management infrastructure because it acts as a repository for information (Bharadwaj, 2015). In this way, knowledge can be reliably stored and retrieved at any time. Thus, technology is a tangible resource for knowledge management and has been used by different organizations to support knowledge management initiatives. Bharadwaj (2015) also say that technology has many aspects to it, which include the hardware, software, middle ware and protocols. These elements of technology often facilitate encoding and information exchange in organizations.

Some of the information technology resources available in knowledge management include knowledge-oriented technologies, functional-oriented technologies, specialty-oriented technologies, and social networking technologies (Ray, 2013; Ngeloo, 2017). The most common knowledge-oriented technologies include groupware and web browsers. These resources help companies to process their knowledge management issues and, by extension, improve how they manage their intellectual capital resources (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013). Function-oriented technologies could include robotics, desktop computing technologies and such like tools of knowledge management (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013). They are mostly aimed at improving operational level practices. Such practices may include production, service delivery, and data processing. Specialty-oriented technologies are often for advanced operational processes in organizations because they are associated with facilitating specialized organizational functions (Bharadwaj, 2015). Typically, such organizations require a high level of knowhow (Ngeloo, 2017). Some of these technologies include computer-aided designs and expert systems software. Lastly, social networking technologies for knowledge management include platforms, such as web 2.0. They are important in facilitating collaborations between team members or enhancing information dissemination within the organization (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013).

Most technological tools applied in knowledge management today tend to use one or more tools, such as groupware web browsers, data mining tools and group decision support (among others). However, knowledge portals are the most commonly used tools in different organizations around the world because they have been proved to significantly improve knowledge management systems (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013). Groupware is often used to foster collaboration between different knowledge centers in an organization. According to Bharadwaj (2015), information technology tools that foster collaboration include databases and performance management systems. An integrated performance support system and knowledge platforms are other areas of knowledge sharing where collaboration can be fostered (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013). Bharadwaj (2015) believe that information technology tools play four key roles that include seeking and identifying related contents, flexibility that help express the contents of the various backgrounds where knowledge is utilized and defining and storing data (among many others).

Based on the above findings, technology emerges as the main resource for developing knowledge management solutions. Indeed, as Bharadwaj (2015) point out, technology acts as the repositories for unstructured information or knowledge exchange. It is also the platform for storing structured data using different tools such as data warehousing and management. Although technology has been touted as being the most useful resource for knowledge management, other researchers have shown that having an effective knowledge structure is also a critical part of developing a reliable infrastructure for knowledge sharing.

Knowledge structure: Bharadwaj (2015) says knowledge structure involves different elements of design that characterize the knowledge management system. They include how organizations have designed their structures of reporting, articulated their communication policies and devised their incentive provision systems (Bharadwaj, 2015). Based on this analysis, the knowledge structure consists of dynamic processes that outline how knowledge should be shared in an organization. Most organizations often have cultures that define the kind of knowledge structures exist in an organization (Kriesi, 2012). For example, most companies categorize their employees into different groups that are defined by their experiences, skills, time, output, or types of clients served (Meier-Comte, 2012). Some of these structural elements of organizational processes are often highlighted to be responsible for poor collaboration within knowledge management teams (Bharadwaj, 2015). For example, bureaucratic processes that exist within organizations often lead to slow decision-making processes and the failure of people to interact freely. Based on such outcomes, knowledge structures form a critical part of the infrastructure needed for knowledge sharing. Studies have also shown that having a supportive knowledge culture also contributes to the quest by organizations to develop strong infrastructures for managing their intellectual capital resources.

Knowledge culture: Knowledge culture is not different from organizational culture, except that it mostly focuses on knowledge as a key strategic resource. Relative to this assertion, Bharadwaj (2015) says that an organizational culture could be used to leverage knowledge management. Similar to the dual nature of organizational culture, a knowledge culture could inhibit or facilitate knowledge sharing within an organization. Indeed, as Bharadwaj (2015) points out, culture often has a significant influence on organizations because it affects the efficiency of knowledge management systems. Its power in doing so mostly stems from the ability of culture to define the values and norms that dictate employee behaviors and practices (Ray, 2013; Ngeloo, 2017). Concisely, the presence of an effective knowledge culture is integral to the success of many organizations that want to excel in knowledge management because it signals the commitment of management to knowledge sharing initiatives (Ray, 2013). In this regard, organizations benefit from a superior decision-making structure.

A sound knowledge culture should support the formal and informal sharing of knowledge. Other researchers add that an effective knowledge management culture should provide a vision that supports knowledge sharing (Ivey, 2014; Bharadwaj, 2015). For example, Bharadwaj (2015) defines an organizational culture that mandates older workers to share their knowledge with younger and less experienced ones. Nonetheless, to realize the benefits of this type of culture, there should be sound leadership at various levels of management (Ivey, 2014). Such leadership acumen should include a strong willingness of management to empower and involve employees at different levels of decision-making. Middle and front level managers have a more important role to play in nurturing such a culture because they are the points of contact between employees and management (Ivey, 2014). Nonetheless, as Bharadwaj (2015) point out, “Leadership is required to develop a desired culture and, ultimately, to develop a knowledge culture as well” (p. 423).

Mechanisms to Fill Knowledge Gaps

Haider and Mariotti (2017) conducted a case study to understand how companies manage their knowledge systems. They established that managers often interacted with technical workers, such as engineers, to fill their knowledge gaps (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). One of the methods used to do so was on-the-job training. Training courses and lectures, plus plant visits and in-house training, were also other methods used by the employees to reduce their knowledge gaps (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). The main salient features that attracted the organization to these methods of knowledge exchange was that they allowed the managers to acquire knowledge that they would have otherwise not have gotten. The arguments made for these unique types of knowledge exchange forums are explained below.

On-the-job training: It was established that employees who were on the job training were better placed in acquiring new knowledge if they worked with more experienced employees through on-the-job training processes (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). Through such a platform, it was easy to learn new information about organizational processes, such as simple information relating to machine operations. Complex processes, such as how to improve organizational practices could also be learned this way. Research studies undertaken by Haider and Mariotti (2017) also showed that this method of knowledge acquisition was the most widely accepted and used by most organizations. In most cases, on the job training often started with a three-month course that was first focused on a language course. It was mainly used in multicultural contexts. Evidence of its application exists in organizations that had both Japanese and English-speaking employees (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). Such a course was not only aimed at imparting language skills, but also educating the employees about the values, philosophies and cultures of each group of workers. In most of these sessions, workers spent time with their colleagues on the factory floor. In one of the assertions made by an employee, it was established that new workers learnt a lot from on-the-job-training because it was happening in real-time, as the job was being done.

In one session that involved training new workers in a heat treatment shop, it was established that the first step of on the job training was educating the workers about all the processes involved (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). In order of processing, employees learnt about each process systematically. For example, if the first process involved jig setting, such was done first. Later, the trainees learnt about how to operate machines, in the order of importance. Generally, the process involved on-the-spot practical training for all the workers. No classes were involved, but new employees often jotted down some notes regarding what they learned. Comprehensively, this example shows that on-the-job training is one practical way organizations have used to fill knowledge gaps. Another one is plant visits and observation, discussed below.

Plant visits and observations: Plant visits involve employees being taken to a company’s plant to observe how operations are being undertaken. These visits could involve a trip to a factory plant or to another company (Aanestad & Bratteteig, 2013). Haider and Mariotti (2017) provide us with another example of how it worked in their organization. Their training process involved understanding how their employees implemented different systems and understood how the processes were relevant to their training course. The main goal of doing so was to make sure the employees understood how operations were being carried out in their respective companies (Haider & Mariotti, 2017).

Other case studies have been cited in several multinational organizations, including Massey Fergusson and AHl which undertake case studies of their own to understand how other organizations perform their organizational processes (Schiedat, 2012). One employee at AHL said that the exercise involved evaluating quality control procedures between the organization and several others (Schiedat, 2012). Comprehensively, this attempt shows how different organizations evaluate their operational processes using a strategy that closely resembles the benchmarking process.

In-house on-the-job training: As insinuated in the name of the concept, the in-house on the job training method involves educating employees about how work is done within the confines of their organization. Therefore, unlike other training methods that include external parties, this method only involves the concerned organization (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). This reason justifies why it is called “in-house training.” However, some literatures present an opposing view to this narrative because they say that knowledge transfer could also involve external stakeholders since outside parties could come to an organization and educate their employees about operational procedures (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). This observation has been reported in an organization called MTL where engineers from another organization (Massey Ferguson) came to share their knowledge about operations processes with employees working for the company (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). Nonetheless, this method does not differ much from the other methods highlighted in this review, in the sense that training and knowledge transfer occurs on-the-job.

In-house training school: Corporations that want to internalize knowledge transfers by developing training schools within an organization have adopted this method (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). Usually, these schools involve the development of curriculums that are solely designed for a specific group of employees or department. Within this internalized knowledge transfer system, it is possible to find selected organizations inviting people from outside the organization to share their knowledge regarding a specific knowledge area (Sloan, 2014). Generally, based on the above assertions, we find that different modes of sharing information within organizations outline different forms of social interaction and knowledge exchange.

There are several cases where organizations have sought the input of third parties in intellectual capital management and in so doing have found enough supporting information to satisfy the needs of all their stakeholders (Haider & Mariotti, 2017). However, there are instances where such knowledge has been transformed to eliminate gaps in intellectual capital management experienced by specific organizations. This outcome was often visible in cases where the knowledge obtained from the external parties was deemed inapplicable to the local context. Usually, when such exchanges and transformation occur, innovation and knowledge creation also suffice. Although the knowledge transformation process happens to fit the knowledge gaps identified in specific organizational processes, it was established that the transformation occurred because employees were the first to note the need for the transformation, relative to the gaps present in their organizations (Haider & Mariotti, 2017).

The inability to transfer knowledge from the partners to the concerned organizations largely arose from differences in working environments. For instance, in the example highlighted above, pitting Japanese and English employees, Haider and Mariotti (2017) found that Japanese products and processes helped to create products that were not directly applicable to the English markets because of several demographic and environmental variations. Therefore, there was a need to introduce changes in the product specification standards. The changes to be made created some sort of knowledge gap in the organizations concerned. Although companies often deliberate on such gaps before engaging in knowledge transfer with other companies, researchers established that employees who were engaged in on-the-job-training often filled such gaps by brainstorming with their counterparts on the work floor (Haider & Mariotti, 2017).

Benefits of Knowledge Sharing