Summary

Bilingualism has been a matter of detailed exploration for decades. The peculiarities of modern human society make this phenomenon common for many regions or populations. Globalization contributes to the increase in the number of bilinguals or even multilingual individuals as people interact with different groups in diverse settings. In addition to providing multiple advantages related to business and daily routines, bilingualism is associated with various positive effects on brain development and functioning. It is believed that bilingual people’s brain deteriorates at a slower pace compared to monolinguals, but developmental changes still occur (Whitford & Titone, 2017). However, insufficient evidence is available on the matter, and further studies are necessary. The use of technology facilitates the process, and new insights are gained with the help of imaging or EEG/ERP, which is specifically valuable when studying brain development. The proposed study will be concerned with the comparison of brain functioning with a focus on the switching of bilinguals in different age groups.

Literature Review

Bilingualism and Multilingualism

Bilingualism and multilingualism (hereafter, these phenomena will be used interchangeably) have been analyzed in terms of the peculiarities of bilinguals’ cognition and perception, as well as language processing, cognitive and perception differences between bilingual and monolingual people, and the characteristics of bilingualism in people of different ages. Bilingualism is referred to as the ability to process two languages, while multilingualism is an individual’s capacity to process several languages (Hayakawa & Marian, 2019). Hayakawa and Marian (2019) have explored the neural structure of bilinguals and monolinguals and stated that the latter have stronger and more complex neural networks, which is associated with better cognitive functioning. Notably, researchers have added that monolinguals’ and bilinguals’ performance may differ depending on the task and involved brain areas. Hayakawa and Marian (2019) have stated that multilingualism also affects the way people process languages and perform other connected tasks. It is stressed that a more comprehensive approach to multilingualism research may be beneficial and that researchers can concentrate on a combination of functions rather than focusing on a single parameter.

The research on language processing suggests that bilingualism is associated with positive changes in brain structure and functioning, resulting in people’s better cognitive performance. For example, Grey et al. (2017) have found that bilingual adults’ processing of a new language is more efficient as compared to monolinguals, and the former display cognitive processes typical of native speakers when processing languages. Structural and functional differences between the brain of bilingual and monolingual people have been analyzed in detail as well (Anderson et al., 2018). However, the peculiarities of specific functions and processes that take place in bilinguals need further analysis (Anderson et al., 2018). Language processing is a complex phenomenon, including diverse components such as switching, decoding, encoding, attention, memory, and so on.

Differences Between Younger and Older Bilingual Adults

As with any other function, language processing ability changes with age, which has been examined in relation to diverse aspects of the issue. Developmental changes lead to poorer cognition and perception in older adults. Neural networks and brain structure transform, which leads to lower processing capacity (Whitford & Titone, 2017). For instance, reading first- and second-language texts differs in younger and older adults, which is associated with the functional changes that take place when people age (Whitford & Titone, 2017). That, in some areas, such as word predictability, no meaningful difference was found, so this kind of cognitive process is not affected by developmental changes in older adults (Whitford & Titone, 2017). Therefore, some functions remain unchanged or even develop with age, which can be related to enhanced language processing capacity. At that, the studies resulting in similar findings are not numerous, which may be accounted for by researchers’ concentration on a set of processes and functions that are mainly linked to attention, problem-solving skills, and other specific language processing components.

In the domains such as subcomponents of attention, bilingual older adults display better results as compared to older monolinguals. When older and younger bilinguals are under study, the latter respond slower compared to younger bilinguals (Dash et al., 2019). Moreover, recent research suggests that multilingual perform and function differently in diverse social settings, and their knowledge and skills are not often associated with age or other characteristics (Pot et al., 2018). Therefore, further research may shed light on the differences between younger and older bilinguals in terms of different aspects of language processing and use.

Switching

Switching is one of the key tasks bilinguals perform on a daily basis when using different languages. This process encompasses the disengagement of one language and the engagement of another one (Blanco-Elorrieta et al., 2018). Switching is mainly characterized by enhanced activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex. Pot et al. (2018) have stressed that switching often occurs with the consumption of less effort in bilinguals. However, it is acknowledged that monolinguals often perform switching tasks as well when decoding diverse cues. Switching helps individuals to solve various problems in all spheres of their life. For instance, switching is an integral part of people’s routine and social interactions. Hence, this skill needs careful examination using a comprehensive approach as the analysis of the performance of particular tasks in laboratory settings can hardly compare with switching in natural contexts.

Research on switching peculiarities in multilingual tends to involve the comparison between this group and monolinguals. It is found that bilinguals display increased sustained attention as well as more rapid task-set reconfiguration as compared to monolinguals, which is attributed to the use of different processing methods monolinguals and bilinguals employ (López Zunini et al., 2019). Dash et al. (2019) also found that bilingual older adults outperform monolinguals of the same age group in task-switching, which is associated with higher attentional control and neural efficiency. Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen (2017) note that switching and overall language processing are less effortful in natural settings rather than during laboratory experiments. The researchers have claimed that bilingualism is a social phenomenon, so it may require a shift in the usage of techniques and methods.

Researchers have paid considerable attention to the analysis of the difference between the switching capacity of bilingual and monolingual older adults (López Zunini et al., 2019; Rieker et al., 2020). However, less attention has been devoted to the comparison of switching of bilinguals of different ages. At that, it is important to estimate the capacity of older age groups to trace any changes that take place with aging. A focus on switching as one of the elements of language processing can provide insights into the different aspects of brain functioning unrelated to the linguistic sphere.

Behavioral Neuroscience and Methods Employed to Analyze Bilingualism

Numerous methods and designs have been utilized to explore the peculiarities of bilingualism and related phenomena. Recently, behavioral and neuroscientific methods have prevailed and proved to shed light on numerous mechanisms associated with bilingualism and processes that take place in the human brain. The development of technology has enabled scientists to expand a range of methods and strategies they could employ. Now, researchers manage to examine participants’ behaviors and the changes that take place in brain structure or functioning in different settings (Poarch & Krott, 2019). Eye movement, reaction speed, and the ways tasks are performed provide insights into people’s behavioral patterns. These techniques were the primary research method, but now they have started playing a more complementary role as neuroscientific tools are available.

The use of electroencephalogram (EEG) and the recording of the so-called event-related potential (ERP) have been widely used in modern research of bilingualism. Brain imaging is another common technique, but it requires more advanced equipment (Grundy et al., 2017). EEG and ERP imply the use of electrodes that are placed on the scalp (in specific locations). The electrodes measure the variation of electrical brain activity associated with the functioning of the bulk of brain cells (Grundy et al., 2017). These tools help researchers to identify the exact brain areas involved in each process related to processing languages. The extent to which these areas are activated in different groups of people or in diverse situations is another domain to be explored.

This brief review of recent literature suggests that various aspects of multilingualism have been analyzed with the use of diverse methods and techniques. Nevertheless, certain gaps are still apparent and need further exploration. For instance, although the superior cognitive ability of bilingual older adults as compared to older monolinguals is properly researched, the comparison of similar functions in bilinguals of different ages (or genders or socioeconomic groups) has not been implemented in the necessary detail.

Each component of language processing in different populations among multilingual is also an important domain to be further investigated. It is possible to assume that older bilinguals may perform better in social contexts as they have developed diverse skills due to their longer exposure to such environments. For instance, Pot et al. (2018) have stressed that the intensity of language use enhances language processing skills irrespective of age. As mentioned above, a shift towards more natural contexts in research is becoming more common in academia, which is beneficial for research in bilingualism. Therefore, the present study will aim at addressing some of the gaps highlighted in this brief review of the current literature on multilingualism.

Research Questions and Hypothesis

The purpose of this study is to identify the difference between switching capacity in bilingual younger and older adults. As mentioned above, quite a considerable bulk of data on switching in older adults is available (Cargnelutti et al., 2019; Chan et al., 2020). At that, the performance of this cohort is often juxtaposed with the capacity of monolinguals of the same age group. The focus of this study is also on the performance of bilinguals in situations close to real life. Researchers’ attention to this aspect has been limited, although some studies have been implemented, such as the research by Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen (2017). The researchers included elements of real-life situation simulations and unveiled certain peculiarities of people’s switching.

Based on the previous research, it is possible to hypothesize that older adults will exhibit poorer switching capacity compared to younger bilinguals due to the developmental peculiarities of the two age groups. It is also possible to hypothesize that older bilingual adults have lower switching capacity when completing real-life simulation tasks compared to younger bilinguals as the overall brain functioning deteriorates with age. The null hypothesis can be formulated as follows: No statistically significant difference in the switching capacity of older bilingual and younger bilingual adults can be found.

In order to address the hypothesis guiding this study, the following research questions are posed:

- Do younger bilinguals perform better on switching tasks in laboratory settings compared to older bilinguals?

- Do younger bilinguals perform better in real-life simulation tasks compared to older bilinguals?

Methods

Participants

The participants will be recruited among the residents of a community that is culturally heterogeneous. Home-residing older adults and the residents of nursing homes above 65 years old will be recruited with the help of handouts and leaflets sent to nursing homes and distributed in residential areas (in parks, stores, supermarkets, non-profit organizations, and healthcare facilities). Younger adults (aged between 35 and 45 years old) will be recruited with the help of the leaflets and online advertisements. Caregivers or relatives of older participants will be able to participate in the research.

The major inclusion criteria will be the participants’ linguistic status. Bilinguals (including multilingual people) speaking English and Spanish irrespective of other spoken languages will be included. The English and Spanish languages are chosen due to the number of Hispanic people in the community. The expected sample size will be 300 people (150 younger and 150 older individuals). Ideally, approximately 70 people in each age group will be males to ensure the heterogeneity of the sample. The recruitment process will be terminated when the expected number of participants sign written consent forms. That, if the gender distribution is not met, the recruitment process will be continued.

This number of participants is sufficient for the purpose of this study. Although the generalizability of the research will be limited as the study will include the residents of a comparatively small community, the research will unveil an existing difference (if any) between the two age groups as far as switching is concerned. The research will also serve as a pilot study using a real-life simulation element that can be further developed and employed with a larger sample. As mentioned above, language has been regarded as a social phenomenon (Blanco-Elorrieta et al., 2018). Therefore, laboratory restrictions may be associated with potentially distorted (at least to a certain extent) data regarding people’s usage of languages in real-life settings.

The leaflets will contain a general description of the study and the contact details of the researcher. Those who will contact researchers will receive more detailed information in invitation letters that will include a brief description of the research and a written consent form. Although in many cases, the major goal and objectives established by researchers are not articulated in order to avoid bias. Those who will sign the form and send it via one of the methods (a letter sent via post, email, a picture sent via a mobile device) mentioned in the invitation letter will participate in the study.

Procedure

This study will encompass a combination of techniques based on the utilization of EEG/ERP technology. The participants will complete surveys containing demographic details prior to the main part of the experiment. Participants will be offered two options: they will be able to complete the questionnaire online at any time prior to the time of the experiment, or they will complete the questionnaire before the experiment. The questionnaires will include the following data: age, gender, ethnicity, spoken languages, employment status, education, marital status, residential status (home, nursing facility, and so on), and income. This approach can help in reducing the time of the experiment implementation without any negative effects.

After the completion of the questionnaires (or when the participants arrive if completed surveys are available), the samples are invited into the laboratory, where they perform two tests. The equipment will include a desktop computer (and the participants will have two white buttons on the keyboard for choosing among the alternatives) and Matlab software. The room will be deemed in order to make visuals more visible, and external noises will be minimized as the participants will complete tasks one by one. Any distractions will be removed to avoid potential distortions or errors. The participants will be asked to concentrate on doing the assignment, which should contribute to their diligence. The participants will have electrodes on their heads to measure their brain activity.

In order to address research question 1, a modified color-shape task switching used by Chan et al. (2020) will be used. The participants will be asked to categorize a colored shape by its shape (triangle or square) or its color (blue or yellow). The task cue for the color-based task will be a round shape with a color gradient on the screen. The task cue for the shape-based portion of the test will be a set of four round shapes. The participants will have 10 trials to prepare for the test and will have a mixed block of 20 shapes and 20 colors trials. The variable in this test will be the switching (non/switching) cost reaction time (RT) and global RT (mean overall RT). The latency and amplitude will be the measurements denoting switching cost. It is also possible to note the brain areas that are activated when this or that task is performed.

The real-life simulation component will imply the use of a combination of visual and audial cues based on a modified test employed by Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen (2017). Two bilinguals will be asked to have a conversation on a set of topics, and their conversation will be recorded. They will provide their consent for recording the conversation and taking a few pictures for the development of the visuals for the study. The conversation will be divided into several sets of records based on the discussed topic. The speakers will use one language (either English or Spanish) during some parts of the discussions. They will also switch languages without any external cues or transitions.

The participants will be first introduced to the speakers by viewing the pictures and listening to their introductory utterances. Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen (2017) have noted that the introduction of speakers makes the situation closer to a real-life environment where people have to meet and interact with their interlocutors. After a one-sentence introduction, the participants will be given some time to look at the picture and simply relax to prepare for the test per se which will commence with an audial cue.

The participants will be asked to choose between two alternatives based on the topics discussed. First, the participants will see a picture of the two speakers discussing an item in one of the languages. Two words will appear on the screen immediately after the audial input, and the participants will choose between two items (on the left and on the right) based on the extract they heard. The participants will listen to 30 trials (short records in two languages) that will be switched randomly. The records will be no longer than 30-45 seconds to avoid positive issues related to poor memory or attention. The participants will need to press the right or left button according to the information they hear. The participants will have five trials to prepare for the test as well. The variables will be the same as in the previous test (switching (non/switching) cost RT, global RT, latency, and amplitude).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to analyze participants’ demographic data. The calculation of the variables mentioned above will be conducted with the help of separate hierarchical multiple regressions. Statistical software will be employed to avoid errors and increase the efficiency of the analysis process. The analysis of the correlation of the participants’ age and their switching capacity will be the focus of this study. Other demographic details will be discussed briefly, and some assumptions can be made, which can serve as a background for new studies aimed at more specified cohorts. The primary attention will be paid to such aspects as age and education level. It can be assumed that people with a high-school education or higher are likely to perform better irrespective of their age.

Timeline

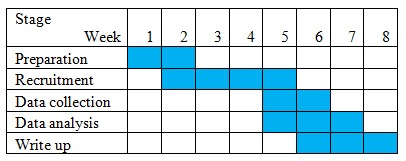

The proposed study will last from seven to eight weeks, depending on the recruitment period (see Table 1). The preparation stage will involve the development of leaflets, further refinement of the methodology, and obtaining all the necessary permissions from facilities and organizations (as well as the laboratory) to distribute leaflets. This phase will also include the recording of the conversation and material preparation (developing tests). This stage will take up to two weeks, and it can overlap slightly with the recruitment process.

The recruitment process may start on week 2, depending on the readiness of organizations to cooperate. The recruitment process may take up to four weeks, but data collection may start during week 5 only. No simultaneous implementation of these stages is possible as it will be necessary to start data collection when all participants provide the written consent forms as the recruitment process may stop after saturation as it is decided to achieve even gender distribution in both age groups. The recruitment process involves such components as reaching people, responding to calls (as well as visits, emails, and so on), and contacting the participants who have signed the written consent form in order to agree on the time of the experiment implementation.

Data collection may take up to two weeks as a considerable number of participants will take tests in a laboratory. Data analysis will last for up to three months and may start on week 5 as the measurements can be processed as far as they are obtained. The write-up may start on week 6, or even earlier, as some parts of the paper do not require the availability of the results of the experiment. These sections include literature review, theoretical foundation, and introduction, as well as some parts of the significance of the study and its limitations. These are quite tight deadlines, but the project can be conducted within this timeframe.

Significance of the Study

The Impact on the Field of Multilingualism

The proposed study can have multiple effects on the development of the field of multilingualism research. First, the research will provide insights into the mechanisms of bilingualism in a particular area of language processing. Switching is an important aspect of language processing, as well as overall cognitive function (Zhang et al., 2020). People’s ability to switch is critical in diverse settings, so it is pivotal to explore this skill in detail.

As mentioned above, the current research is mainly associated with the comparison of bilinguals and monolinguals of different ages or gender. Some studies are concerned with the analysis of the difference between younger and older bilinguals. However, little is known about such differences in each aspect of language processing. Switching is one of the areas characterized by the lack of evidence regarding the differences in the performance of younger and older bilinguals.

It is still unclear whether the functioning of the brain differs in laboratory settings and natural contexts. The present study can shed light on these areas and offer a sound methodology for this analysis. This study contributes to the investigation of switching in laboratory and semi-laboratory (or real-life) settings. This area is still underdeveloped and needs substantial exploration. Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen (2017) have emphasized that language should be analyzed in natural contexts as people processing languages are often affected by multiple factors that shape their behaviors and their brain functioning. The researchers have found that the use of real-life simulations uncovers these effects, so this method can be used in further research.

The proposed study also employs similar techniques, so people’s switching in more natural settings can be measured in terms of neuroscientific methods. Clearly, it is difficult to assess some brain functions in truly natural settings that are characterized by various distractions, making it difficult to trace the changes in the chosen variables. However, this study, using the simulation tried in another research, can be instrumental in the creation of an atmosphere close to real-life social interactions. The use of records can be further developed, and the benefits of speakers’ introduction can be verified. This study offers new insights into the blend of behavioral and neuroscientific tools.

The Impact on Society

The effects the proposed study can have on society are also manifold as important data on multilingualism can be obtained. In addition to the obvious benefits of being able to interact with people of diverse linguistic backgrounds, people can acknowledge the positive influence of multilingualism on brain functioning. This research will become another piece of evidence supporting the claim that studying languages can help in preventing brain functioning deterioration associated with aging. If switching capacity does not deteriorate with age in bilinguals, and this ability is associated with other cognitive processes not related to language processing, studying languages can be seen as a way to prevent the development of different mental health issues as well. Recent studies show that bilinguals are better at switching and performing diverse tasks compared to monolinguals. However, this study can be instrumental in gaining insights into the extent to which bilingualism affects people’s cognition at different developmental stages.

This study can become another important source of empirical data to facilitate the development of various programs for adults and older adults to enhance their cognitive capacity. These projects can involve learning a foreign language or training skills multilingual people use (such as switching). The understanding of neurological patterns typical of multilinguals’ language processing can help in creating effective programs for language learners pertaining to different age groups. The programs can be developed for use in education (colleges and high schools) or healthcare settings (nursing homes, community-based health organizations). Thus, the present study can contribute to the development of the educational and healthcare spheres.

Finally, the dissemination of the results of this study can facilitate the discussion of the benefits of multilingualism or learning foreign languages in society, which can be beneficial for many people. Policymakers, practitioners in the fields of education and healthcare, non-profit organizations, and individuals can collaborate to create effective educational incentives and promotional campaigns. It can be beneficial to develop a promotional campaign using empirical data and motivating people to learn at least one foreign language.

References

Anderson, J. A. E., Grundy, J. G., De Frutos, J., Barker, R. M., Grady, C., & Bialystok, E. (2018). Effects of bilingualism on white matter integrity in older adults. Neuroimage, 167, 143-150.

Blanco-Elorrieta, E., Emmorey, K., & Pylkkänen, L. (2018). Language switching decomposed through MEG and evidence from bimodal bilinguals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(39), 9708-9713.

Blanco-Elorrieta, E., & Pylkkänen, L. (2017). Bilingual language switching in the laboratory versus in the wild: The spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptive language control.The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(37), 9022-9036.

Cargnelutti, E., Tomasino, B., & Fabbro, F. (2019). Language brain representation in bilinguals with different age of appropriation and proficiency of the second language: A meta-analysis of functional imaging studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 1-19.

Chan, C. G. H., Yow, W. Q., & Oei, A. (2020). Active bilingualism in aging: Balanced bilingualism usage and less frequent language switching relate to better conflict monitoring and goal maintenance ability.The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(9), e231-e241.

Dash, T., Berroir, P., Joanette, Y., & Ansaldo, A. (2019). Alerting, orienting, and executive control: The effect of bilingualism and age on the subcomponents of attention.Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 1-12.

Grey, S., Sanz, C., Morgan-Short, K., & Ullman, M. T. (2017). Bilingual and monolingual adults learning an additional language: ERPs reveal differences in syntactic processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(5), 970-994.

Grundy, J. G., Anderson, J. A. E., & Bialystok, E. (2017). Bilinguals have more complex EEG brain signals in occipital regions than monolinguals. Neuroimage, 159, 280-288.

Hayakawa, S., & Marian, V. (2019). Consequences of multilingualism for neural architecture. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 15(1), 1-24.

López Zunini, R. A., Morrison, C., Kousaie, S., & Taler, V. (2019). Task switching and bilingualism in young and older adults: A behavioral and electrophysiological investigation. Neuropsychologia, 133, 1-10.

Poarch, G. J., & Krott, A. (2019). A bilingual advantage? An appeal for a change in perspective and recommendations for future research. Behavioral Sciences, 9(9), 1-13.

Pot, A., Keijzer, M., & de Bot, K. (2018). Intensity of Multilingual language use predicts cognitive performance in some multilingual older adults.Brain Sciences, 8(5), 1-27.

Rieker, J. A., Reales, J. M., & Ballesteros, S. (2020). The effect of bilingualism on cue-based vs. memory-based task switching in older adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 1-11.

Whitford, V., & Titone, D. (2017). The effects of word frequency and word predictability during first- and second-language paragraph reading in bilingual older and younger adults.Psychology and Aging, 32(2), 158–177.

Zhang, H., Wu, Y. J., & Thierry, G. (2020). Bilingualism and aging: A focused neuroscientific review. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 54, 1-18.