Abstract

The paper looks into the stakeholders and the reasons behind the trend of adopting green operations. It also examines the limits of environmental management in business. The study revealed that people get into green business practices for cost savings, to build innovative cultures, increase shareholder value, attract and maintain customers and to enhance employee retention or satisfaction.

Some businesses have chosen not to pursue solid environmental strategies, and have selected for green washing. However, this dishonest approach could harm them in the long and short run. It was also found that green strategies will become more imperative for businesses in the future. Firms will become more proactive and governments more carefully observant.

Introduction

Environmental sustainability has gradually entered the ordinary business environment. Organisations are finding new and creating ways of going green. Furthermore, a number of them now know that the there is a business case for environmental management. All organisations have certain responsibilities due to the fact that they have many stakeholders which have an interest in their operations.

Even the most basic organisation will have more than just the owner as a stakeholder. The larger the organisation, the greater the number of stakeholders that it has, the more complex will be the decision-making process (Huff, 1982), This is due to the fact that decisions need to bear in mind various influences and pressures affecting many stakeholders (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991).

These issues become more complex because some stakeholders may have different demands and expectations from the organisation. As the world becomes more environmentally conscious, the demands of stakeholders are more emphasised on ensuring environmental sustainability (Orlitzky, Siege & Waldman, 2011).

Purpose

The purpose of the study is to determine who are stakeholders and what is their reaction to environmental sustainability and why many businesses are going green. It essential to determine the motives and goals behind the strategy in order establish whether this is a reasonable approach. Additionally the report will clarify the wrong and right approaches to environmental management through an analysis of its effects.

Scope

With reference to the above purpose, the scope of the report will be around the stakeholders as well as the reasons behind managerial consideration of stakeholders’ views, the monetary and non monetary incentives for going green, and the effects of green washing on environmental sustainability. Aspects that do not relate to business outcomes will not be covered in the report.

Literature review

Why managerial decisions are affected by many stakeholders

Businesses do not operate in isolation; they belong to communities that could be local or global. Consequently, their activities and decisions have a direct impact on their direct partners as well as isolated contacts. Therefore, flexibility is imperative in ensuring that the voices of all stakeholders are incorporated into a company’s business practices.

If expectations about a certain aspect of business change, then managers ought to change with it. Policy makers, buyers, shareholders and non-governmental organisations may raise concerns about the importance of a certain issue, such as globalisation. It is the right of the concerned institution to ensure that it listens to these players or else its short term and long term prospects for continuing in business may diminish (Sommer 2012).

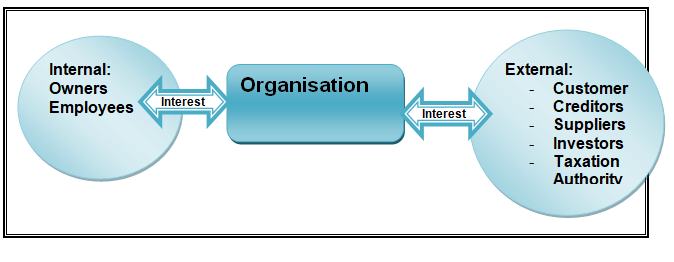

Each organization has a number of stakeholders and those organization are affected by their stakeholders such as employees, customers, consumers, advertisers, investor, suppliers, creditors and government, taxation authorities (see Exhibit 1).

Each one of those stakeholders have different interests due to their different purposes towards an organization. Orlitzky,Siegel and Waldman(2011) provided an example “multinational firms are increasingly pressured by numerous stakeholders to engage in social and environmental responsibility” (p. 6).

A manager’s key responsibility is to his shareholders, as he is obligated to make decisions that will increase shareholder returns. In the past, corporate social responsibility and environmental management were regarded as ethical initiatives. They were seen as strategies that gave businesses a humane side, but were not directly linked to the bottom line.

However, in recent times, many administrators have realised that there are positive business gains to be made when pursuing such initiatives. If a manager has the opportunity to increase both long term and short term prospects for staying in business, then he ought to seize those opportunities seriously (Carroll & Buchholtz 2012).

Growing trend among organisations to be green

Numerous organisations are going green owing to the cost savings that come from the practice. Gone are the days when stakeholders regarded such strategies as little more than benevolent work. Now, companies have realised the monetary benefits of environment sustainability. Cost savings root from the use of fewer raw materials or resources as green policies advocate for minimisation of waste.

Several green organisations often reduce the energy they consume and spend less of water. Furthermore, a number of them may get their raw materials from close suppliers, which saves fuel.

Additionally, savings come from the reduction in operational costs as only the most necessary processes in a firm are maintained. Numerous mid-level and large enterprises have reported cost savings of millions of dollars annually. However, initial investments must be made in order to realise these benefits (Willis 2009).

Many organisations are incurring numerous losses due to fines that come from environmental mismanagement. The Australian government has strong environmental conservation laws that can attract heavy penalties if broken. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, they may even lead to closure of the business.

Aside from that, wasteful ways of doing business always lead to unnecessary expenditure or procedures (Damall et. al. 2006). For example, a company that responsibly handles its waste will not have to spend a lot on disposal fees or licenses required to discharge certain amounts of sewer water. A case in point is Inercell, which is a bleaching product manufacturer in Poland.

It went green by buying water reducing and pollution reducing equipment. Within the next 7 years, the organisation realised annual water reductions of 7%. Additionally, the COD (chemical oxygen demand) of the sewer water from the manufacturing plant reduced by 70% in this period of time. The organisation also enjoyed an 87% reduction in the amount of hydrogen sulphide in its waste.

Because of this initiative, the plant no longer had to pay external partners a lot of money to handle their sewer water (Sustainability and IFC 2002). The organisation reduced waste discharge fees by 300%. The general savings enjoyed by the organisation within a five-year period were $ 12 million. Therefore, going green can lead to savings in this way.

Other large organisations like Xerox have saved about 18 million dollars worth of expenditure owing to a 21% reduction in energy use. A firm like British Petroleum has reduced its emission expenses by about 650 million dollars between 2001 and 2010. P&G saves about $380, 000 annually from the recovery of waste water and lighting savings.

Dell also saved 3 million dollars within a period of 3 years due to energy savings while Herman Miller enjoyed a 32% return on green investment. Shown below is a summary of energy consumption changes in buildings over time.

Source: Jawls (2010)

Environmental sustainability also assists businesses in attraction of new buyers or maintenance of their clients. A number of consumers have become increasingly conscious about their environment. Some are willing to pay more for green products or can select a green item if it costs the same as a non-green one. Therefore, businesses that want to draw into new markets or attract a wide range of clients should try green alternatives.

Several western markets are becoming saturated; consequently, successful organisations ought to hold on to their respective consumers. One way of achieving this objective is though green business practices. Companies with a strong environmental reputation often have a loyal customer base because this decision strongly affects buying decisions.

It should be noted that perceptions among consumers concerning the environment depends on their age. The group of individuals who are between the ages of 11 and 33 (the Millenials) have been found to be more environmentally conscious than any other age group. 83% of these members will trust a business more if it is green, according to a research by Cone. Inc.

Additionally, the latter study also indicated that 69% of these consumers think about environmental commitment when buying products (Jawls 2010). Therefore, organisations that focus on green strategies will have a much higher chance of succeeding in the market than those who do not.

Green buyers simply want to take their business to environmentally responsible firms. Shown below is a summary of the case for environmental sustainability as seen through various supporters

Jawls (2010) carried out a case study on how companies realise cost savings and found the following

A case in point was that of an Indian textile maker known as Century and Textiles Industries. The organisation had international markets in various parts of Europe, such as the UK and Germany. At the time, a German-based client called Eco-Tex demanded that Century Textiles use environmental dyestuffs. This requirement was in accordance with green standards developed in Europe.

The Indian company complied with its customers’ demand even though it had to spend slightly more money in the short term. However, the changes caused the plant to increase its prices by 10%. Sales volumes increased by the same level (Sustainability and IFC 2002).

Century Textiles was able to draw into a previously ignored market in the UK and US. It was the first Textile Company to ever have such strict environmental laws and this led to their success. The brand differentiated itself from its competitors through green strategies.

Small organisations that sell their commodities to local economies may find that they are able to increase customer loyalty within such groups. If a company pursues a base of green strategy, then chances are that it may choose to source its commodities from the local community and get its employees from the same location and even develop the local economy.

This is good public relations for the organisation as it integrates into the fabric of its community. Such efforts may translate into higher revenue flows for concerned organisations because when they empower a community, then the community’s spending power also increases for the benefit of the green company (Sustainability and IFC 2002).

Companies also use green strategies in order to get and maintain the right employees. Employees often look out for companies that are firmly committed to the environment or who at least consider this as part of their portfolio. Jawls (2010) explains that 40% of all the MBA graduates said that they regarded environmental sustainability as a vital part of their job-hunting strategies.

Furthermore, those employees who already belong to an organisation have higher chances of being productive if their employers have a green policy. Many of these employees have great satisfaction and will be characterised by low turnover. Part of the reason for these high rates of success is the high level of engagement by the employees.

Most of them will be highly motivated and will also feel like their contribution to the company matters. A Globescan report indicated that 83% of the employees interviewed were motivated by the pursuance of a corporate social responsibility model.

Organisations must frequently look for new fields in order to keeping growing. Environmental sustainability is one of the field for this continued growth. For instance, a company that revises its energy use for green objectives is likely to minimise its costs of operation and overall bottom line. Continually, pursuing such a strategy can lead to greater profit margins and thus higher company growth.

Sometimes certain companies literally benefit from reduction of their environmental impact as this preserves the raw materials. For instance, a manufacturer that uses fewer amounts of a rare material will have more to use in the future and can thus continue to stay in business (Dyllick & Hockerts 2002).

Several companies are going green because it helps them innovate. Businesses that pursue environmentally sustainable strategies often focus on making their operations improve. Many of them use weak approaches to modify and alter their processes, people or products. Such firms develop an ability to look at things differently and respect their leaders.

They also engage employees because such individuals are often looking for ways of improving their current systems. Sometimes these innovations may not just revolve around green products; they may also initiate improvements in genial business. Organisations can then get an opportunity to offer exceptional customer solutions, and thus meet their demand in the future (Elkington 2007).

Going green also promotes a firm’s shareholder value as well as its profitability. Profit increments of 25-30% have been reported by several companies that have stuck to their green strategies.

Most financial success roots from the attraction of productive employees, reductions in operating costs and having a culture of improvement at all times. Certain businesses view environmental management as a new revenue stream. In this regard, they may turn their waste into commercial by-products (Sharma et. al. 2010).

Green washing and its effects on sustainability

Several organisations have learnt about the benefits of going green, although some of them are not willing to invest in the capital required to fully realise these advantages. As a result, many of them have decided to use green-washing as a shortcut to getting the business rewards of environmental management.

These organisations often engage in environmental reporting or marketing, where any slight green initiative is advertised to the public. They also sponsor events or distribute educational material in the name of promoting green living. Some organisations take it to the extreme by promoting themselves as environmentally-friendly organisations when evidence indicates otherwise.

The main objective of green-washing is to create an impression that a company is dedicated to environmental sustainability in order to get positive responses from consumers or other stakeholders even when this is not true. (Kewalramani & Sobelsohn 2012)

The above strategy may seem beneficial to an organisation in the short term, but it is not good or harmful to the process of environmental sustainability. Any company that does green-washing is misleading or dishonest with the public.

It is conducting business unethically and making people believe that their version of environmental sustainability is actual and true. This is dishonest, and it destroys the main principles of business success (Davis 1992).

These green washing organisations may also face immediate financial loss if discovered by the public. One way of losing market share would be through diminished exposure and reduced consumer confidence. People would associate the brand with a lie and thus question others aspects of the company’s products. Alternatively, some businesses may face litigations from angry or frustrated consumers.

They may have to pay a lot of legal fees and compensation for making these false claims. A case in point was a plastics bottle manufacture called Enso Plastics in California, USA. The complainant – Kamal Harris – filed a suit against the bottling company because the firm claimed that its bottles were biodegradable.

The customer found out that they were not so he sued them for violating the country’s laws on false marketing (Kewalramani & Sobelsohn 2012). The plastic manufacturer had to pay the complainant party a lot of money and also had to deal with a bad publicity.

If green-washing continues randomly, then chances are that it will create self-satisfaction among regulators as well as consumers. Companies will get away with their unethical practices and their competitors will also join them. This will create a situation where major industries base their practices on magic.

Most of these actions will cause severe effects on the environment as the objectives of sustainability will not be realised. More resources will keep being used and future generations will struggle to meet unbearable living conditions (Elkington 2007).

Green washing may also lead to a general doubt for all environmental initiatives. If going green will simply be regarded as an avenue for self congratulations, then consumers will grow cold towards the whole initiative (Davis 1992).

Many of them will write off any environmental campaign as false and misleading even when this is not true. Therefore, legal organisations will not get an opportunity to inform consumers about their green efforts (Davis 1992).

Discussion

Expected future developments in environmental sustainability

In the future, it is likely that businesses will move away from green washing and publicity to more solid strategies of sustainability. It will no longer be enough to tell customers about what one is doing, but one will need to walk the talk. Consumers are likely to become more cautious about dishonest businesses, so those who insist on misleading them will be outcompeted by the genuine ones (Milne et. al. 2010).

Some companies still think of environmental sustainability in the reactive sense. In other words, they depend on their clients to make it easy for the way for sustainable practices. Most of them wait for consumers to demand green practices prior to adoption of the strategy. In the future, it is likely that businesses will take on a more proactive role in environmental management.

Companies will appreciate the quantifiable and unquantifiable benefits of going green in their businesses. Therefore, many of them will lead from the beginning. They may create new standards for green technology. Alternatively, a number of them may use green strategies to create by-products that may make them money (Sustainability and IFC 2002).

It is likely that green intermediaries will have a huge demand in the future. Many of them will provide the information and expertise needed to be environmentally sustainable. Additionally, companies that provide environmental consultation services or sell green products are likely to have a lot of demand.

For instance, architects that design green buildings or electronic manufacturers that have energy saving light bulbs will be in great demand. In fact, there will be a time when wasteful products will lose market share or even be pushed out of the market by green alternatives (Gray & Bebbington 2000).

The government is likely to play a larger role in green strategies. It will probably create more elaborate or clear standards about environmental responsibility for businesses (Gray & Bebbington 2000). Therefore, individuals will not have an excuse to flout these laws.

Additionally, consumers may also expose those who try to break these rules through green-washing and other negative approaches. In the future, it is likely that businesses will treat environmental regulations in the same way that they treat other legal aspects of conducting business (Kewalramani & Sobelsohn 2012).

Conclusion

This report should have shown and explained that the reasons why there has been a growing trend of organization becoming more “green” in operating in a way that is environmentally sustainable has been in large part due to the environmental movement which has not only taken on a fashionable role in society, but also had a significant impact on sensitising and educating individuals to environmental issues.

Companies are adopting green strategies because it protects them from unnecessary expenditure and facilitates cost savings. In addition, it increases shareholder value, enhances employee productivity, creates an innovative culture and attracts new clients.

These benefits are enough of an incentive to warrant consideration of environmental sustainability. However, companies must avoid practicing their environmentally harmful practices by green-washing as this will backfire on them.

References

Carroll, A & Buchholtz, A 2012, Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management, South Western Cengage learning, Ohio.

Damall, N, Jolley, J & Handfield, R 2006, ‘Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: complements for sustainability? Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 17 no. 1, pp. 30-45.

Davis, J 1992, ‘Ethics and environmental marketing,’ Journal of Business Ethics, vol.11 no. 2, pp. 81-97.

Dyllick, T & Hockerts, K 2002, ‘Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability’, Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 11 no. 2, pp. 130-141.

Elkington, J 2007, ‘Partnerships from cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st C business’, Environmental Quality Management, vol. 8 no. 1, pp-51.

Gioia, DA& Chittipeddi, K (1991). “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation”, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 12, iss. 6, pp. 433 – 448.

Gray, R & Bebbington, J 2000, ‘Environmental accounting, managerialism and sustainability: Is the planet safe in the hands of business and accounting’, Advances in Environmental Accounting & Management, vol. 1, pp. 1-44.

Jawls, K 2010, The business case for environmental sustainability. Web.

Huff, AS (1982). “Industry influence on strategy formulation”, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 3, pp. 119 – 131.

Kewalramani, D &Sobelsohn, R 2012, Greenwashing: Deceptive business claims of ecofriendliness. Web.

Milne, M, Kearins, K & Walton, S 2010, ‘Creating adventures in wonderland: The journey metaphor and environmental sustainability’, Organisation Journal, vol. 13 no. 6, pp. 801-839.

Orlitzky, M, Siegel, DS & Waldman, DA (2011). “Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability”, Business & Society, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 6 – 27.

Sharma, A, Iyer, G, Mehrotra, A & Krishnan, R 2010, ‘Sustainability and business to business marketing: A framework and implications’, Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 39 no. 2, pp. 330-341.

Sommer, A 2012, ‘Environmental sustainability in business’, Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management, pp. 23-47.

Sustainability and IFC 2002, Developing value: the business case for sustainability in emerging markets. Web.

Willis, B 2009, The business case for environmental sustainability. Web.