Marginal productivity in relation to wages is the change in total revenue earned by a firm from employing one more unit of labour. According to Keen, a firm may hire many employees at prevailing wages. However if the input is fixed in the short run, then output will be subject to diminishing returns. This is because each additional worker adds a less amount to output than the preceding worker. The effort applied by that extra worker to the firm may be variable while the wage per unit remains constant. Therefore as long as the wage is equal to the additional employees output that is sold, a firm will continue hiring. Furthermore, if a firm is competitive the extra unit may be sold without reducing the firms’ price. The returns an industry will gain by hiring its prior employees is equal to the price it sells its output, multiplied by marginal product of the last worker (2004, 112-113).

Benjamin, Gidde and Gunderson (2002) argue that “a firm can vary the quantity of labour by either hiring more employees or increasing working hours”. If it opts to increase working hours, then it has to pay higher wages for overtime hours. However, non wage benefits like pensions and medical plans will not fluctuate with each extra working hour. Therefore, it is more cost-effective for a firm to extend working hours for current workers than to hire new employees. Hiring will result in a firm incurring some “quasi fixed” costs that are independent of the number of hours worked. Moreover, non wage benefits costs will be incurred. Furthermore, recruitment and personnel costs, training and termination costs will also be included.

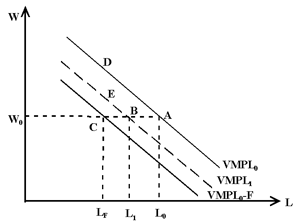

Benjamin et al (2002) suggests that by representing the “quasi fixed” cost of employing a new worker by a constant F. A firm will hire a worker up to the point where the cost of hire is F plus discounted current and future wage payment W, is equal to the current and future Value of Marginal Product of Labour (VMPL).Thus, hiring takes place at F+W=VMPL. Moreover, in an infinite time it will hire labour up to a point where F+W/r=VMPL/r; where r represents discounted interest rate. However, the wage received W will be less than VMPL because a portion of VMPL is used to pay the cost of hire. This can be represented in the diagram below (Para. 1-2).

According to Benjamin et al (2002), for” zero fixed cost” at W0 and VMPL0 a firm hires L0 employees at point A. during recession it will loose L0-L1 employees due to layoffs. For “positive fixed cost” at W0 the firm hires Lf employees at point C. As a result, the fixed cost of hiring shifts the demand curve downwards or backwards to the left. During recession when a firm hires Lf workers layoffs may be avoided. As a consequence, the schedule will shift back to the left. Furthermore, the fixed cost associated with regulating the number of employees generates a lodge between VMPL and the wage rate. This will reduce the rate of layoff for a worker. In addition, a trained worker is important to the firm even if the rate of VMPL is more than the wage rate. This is because the firm will be recovering some of the sunk fixed cost. Therefore, if a firm layoff a skilled worker then W+F will be great than VMPL; this will result into a loss. Hence, a firm tends to hire more skilled workers than unskilled workers and does not dispose of them easily (para.2-4).

Reference

Benjamin, D. Ride, C & Gunderson, M. (2002). Labour market economics: labour Demand, non wage benefits and quasi- fixed cost. (5thE.d). Web.

Keen, S. (2004). Debunking economics: the naked emperor of social sciences (3rdE.d). Zed books. London. New York. United States of America.