Introduction

Once known as a British colonialist trade station, Singapore has evolved into a great South Asian city-state. This is owing to its thriving economy and cultural diversity, which has helped it to become a global financial center. Singapore, blessed with political stability and safety, has had a 7.7% GDP growth since its independence (Abbass et al., 2022). This republic has also been able to sustain constant population growth, with an average of 5.3 million people and a 2% growth rate (McGee, 2019).

As stated by the Singaporean government, this population growth will continue in the next years, as will the cultural variety based on a trade-driven economy that includes a substantial number of foreigners. According to McGee (2019), by 2030, the expected demographic composition will be 50% of immigrants. Singapore may be regarded as an adventure that is evolving and establishing a successful framework and innovativeness for the future.

The Rationale for Choosing Singapore

In addition to its exhilarating and inventive culture, Singapore offers a conducive economic climate for other nations. Contractor et al. (2020), states that just as it is in any other country, it is important to analyze the necessities and protocol within the culture before starting any business in the country. Singapore, luckily, provides various benefits to investment startups. Singapore has created a solid basis for enterprises, making it one of the most suitable and competitive Asian marketplaces (Chiu et al.,2019). Furthermore, according to Chiu et al. (2019), its geographical position is also advantageous since it provides a strong worldwide footprint.

Aside from a strong commercial framework, Singapore has developed user-friendly procedures for founding and running firms (Double-tax agreements in Singapore: Complete guide, 2021). Companies with headquarters in Singapore benefit from a variety of factors, including double-duty avoidance treaties and well-regulated intellectual property laws. As a result, investors frequently choose Singapore seeking low operating expenses, peace of mind, and protection of ideas and techniques that enhance competitiveness in a dynamic worldwide market.

In the majority of nations throughout the world, registering a foreign firm is fraught with difficulties. On the other hand, Singapore has devised a simple procedure for establishing new firms or outlets, allowing them to easily deal with the three branches of government that manage business registration in the country. Singapore’s financial authority has been properly formed to satisfy the standards for various banking, insurance, and other financial company entry (Vives, 2019).

The Legal Service Authority simplifies services in the legal business. Singapore’s all-inclusive global enterprise supports the seamless processing of registration paperwork for any firm. Singapore has also been recognized for its success in building rigid commercial agreements. By effectively overcoming impediments erected by other countries, Singapore has created a framework that promotes inter-agency collaboration rather than confrontation to help companies expand and thrive.

Cultural Analysis of Singapore

Communication

Singapore is a cosmopolitan country with several ethnic groups. According to Wang and Yang, (2022), the Chinese occupy around 77% of the population, Malay constitute approximately 15%, Indians constitute about 6%, and experts comprise around 2%. As a result, the country has four official languages: Mandarin Chinese, Malay, Tamil, and English (Wang & Yang, 2022). Since most Singaporean schools follow the English curriculum, English is the chosen language for conducting international commerce. According to Wang and Yang (2022), the concept of multi-ethnicity leads to different communication viewpoints. It might be low-context or high-context, vocal or nonverbal, and it can include linguistic and cross-cultural difficulties.

Verbal Communication

The most common types of verbal communication in Singapore are indirect communication, refusals, and voice. Verbal communication is communication in which people communicate with actual words. Singaporeans are motivated to use indirect communication because it contributes to maintaining harmonious relationships. To convey meaning, they pay more attention to tone, expression, and posture than words (Yeo & Pang, 2017). They also admit that they frequently understate their views and rely heavily on communication. Indirect communication is favored to preserve conversation coherence and avoid face loss between exchanges.

On the other hand, refusals are portrayed as a type of verbal communication employed by Singaporeans owing to their obsession with politeness and saving face, which leads to the majority of them delivering a negative response to questions to which they do not know the correct answers. They frequently express themselves honestly and are apprehensive about engaging in concept competitions (Yeo & Pang, 2017). On the contrary, Singaporeans dislike conversing with strongly projected voices, viewing them as overwhelming and impolite.

Non-Verbal Communication

Nonverbal communication involves communication through body language and facial expression. According to Yeo and Pang (2017), Singaporeans employ various nonverbal communication techniques, including eye contact, physical contact, body language, rude stroking of someone’s head, and silence. They regard pointing with the index finger as impolite and prefer to nod or use their entire hand in the targeted direction. In Singapore, nodding the head is a prevalent method of nonverbal communication; nonetheless, body language is modest, with movements constrained and uncommon. Many individuals are uncomfortable receiving physical love from strangers; hence physical touch is rarely often employed. Physical contact, such as caressing, embracing, and backslapping, is reserved for close friends (Yeo & Pang, 2017). In most situations, Singaporeans see eye contact as a sign of attentiveness and confidence.

However, certain Singaporeans, such as Hindus and Muslim Malays, frequently divert their eye when talking with superiors. They see extended eye contact as difficult or unfriendly. Silence is one of the most important and deliberate communication instruments in Asian cultures. When someone pauses before addressing a question, it is assumed they have given it due care and thought. Touching someone’s head is likewise considered impolite and disrespectful among Singaporeans.

Religion

Religion is the behavior or activity that represents a belief in, reverence for, or desire to please a divine ruling authority. It may also be defined as the practice or performance of observances or ceremonies suggesting a particular system of worship and religion (McCutcheon, 2018). Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and Islam are the most prevalent faiths in Singapore (Tay, 2019). Multiple rules govern the operation of houses of worship for many religions. For example, people cannot wear shoes in temples or mosques. Similarly, Hindus are required to wash their hands and feet after visiting temples.

Manners

Manners may be defined as people acting in socially acceptable ways and respecting the sentiments and comfort of others. Dining, entertainment, and greetings may all be used to demonstrate Singaporeans’ manners. Any host must make dish orders when in a restaurant in the country. Similarly, before commencing a dinner with a Chinese, an individual must get an invitation from the host. It is also recommended that chopsticks be placed in their proper dumpsites after completing a meal. Discarding the chopsticks suggests that the person still needs to finish their meal (Lim, 2021). It is also customary to always arrive on time while visiting a Malay home. This is because they usually serve dinner first, without any beverages or appetizers. Likewise, visitors are given a water basin and a towel to wipe their hands before serving supper. After meals, Indians want visitors to stay for an extended period to converse with the host family.

Business Culture; Singapore Versus Hong Kong

Dress Code

Singapore is hot and humid all year due to its location on the equator. Business dress codes match the weather and are more casual than in many Western nations or Asian countries such as Japan and Korea (Baker, 2020). As a result, males frequently wear shirts and pants without a tie (jackets are not usually worn.) Colors can be milder than the gloomy blues and greys found in the United Kingdom and Japan. Work-appropriate clothing for women includes skirts, pantsuits, traditional button-up shirts, pumps, and heeled shoes. Accessories should be of high quality but not overbearing (Baker, 2020). In Hong Kong, the dress code varies somewhat depending on the size of the organization and the industrial sector. It is generally best to err on caution and dress professionally. Men wear dark suits, shirts, and ties, and women wear conservative business suits, but pants are typically worn on casual occasions.

Working Hours

In Singapore, the average working day is 9 hours long, or 45 hours a week, with a maximum of 12 hours per day. Singaporeans are workaholics who routinely work 2 hours of overtime every day. The work climate is very competitive and fast-paced, and employees must be willing to work overtime weekly. Working hours in Hong Kong are not fixed. However, normal business hours are usually from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Government offices are normally open from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., while banks are open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (Baker, 2020). Retail store hours and closing times vary, although business districts normally shut around 6:30 p.m., while those in commercial areas typically close at 9 p.m.

Hofstede Cultural Dimension

Power Distance Index

This dimension expresses the degree to which individuals in society recognize that power is allocated unequally, and those lower in the food chain accept and expect this to be the norm. Societies with a large power distance acknowledge the existence of a hierarchy in which everyone has a position (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Lower power distance societies always attempt to equalize power distribution and require that any inequities in power distribution be explained.

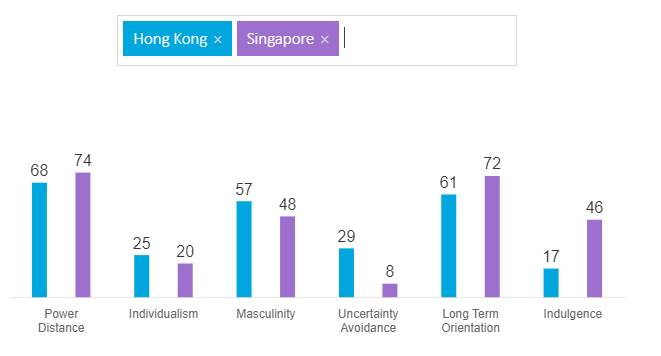

When comparing Hong Kong and Singapore in terms of power distance, Hong Kong has a lower power distance index (PDI) than Singapore. A businessperson from Hong Kong who is accustomed to centralization and unequal power distribution will thus find it simple to succeed in Singapore since they are free to express their thoughts and participate in decision-making. A manager from Hong Kong needs to share responsibility and include the other team members in decision-making to succeed in Singapore.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

Individualism is the preference for a scenario in which people are solely responsible for their well-being. On the other hand, collectivism is a state in which society is close-knit, and individuals rely on family or friends to look after them in exchange for loyalty (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Individualism in Hong Kong is higher (25) than in Singapore (20) (Hofstede-insights.com, 2022). For a Hong Kong businessperson to function well in Singapore, they must address concerns such as appreciating individual successes, avoiding interweaving social and professional life, and fostering discussions and voicing members’ ideas.

Masculinity vs. Feminity

Masculinity, in this context, refers to a society’s preference for achievement, heroism, and monetary incentives for success. A culture like this is extremely competitive. Femininity, on the other hand, is a situation in which individuals favor collaboration, humility, generosity, care for the weak and impoverished, and high quality of life for all (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Hong Kong has a higher MAS than Singapore (57 and 48 respectively) (Hofstede-insights.com, 2022). As a result, a Singaporean businessperson must be aware of distinct gender roles. Singapore is highly competitive, and a Hong Kong businessperson must be tenacious and willing to face severe competition to thrive. This is due to Singapore’s ‘tough’ culture, in contrast to Hong Kong’s sensitive’ culture.

Uncertainty Avoidance

This is a dimension that reflects how comfortable one is with uncertainty and ambiguity. Countries with a high UAI have strict belief and conduct rules, and they do not tolerate negative behavior or ideas. On the other hand, societies with a lower UAI score are more easygoing and preoccupied with practice rather than ideals (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Hong Kong has a better rating of 29 on Uncertainty avoidance, whereas Singapore has a value of 8. This suggests that life is made as predictable as possible, and when they cannot control it, they leave their fate “in God’s hands.” As a result, foreigners in Singapore must be clear about their objectives and set attainable targets. They should also promote collaborative thinking and consultation. It is also important to know that undefined cultural expectations need to be learned.

Long Term Orientation

The pragmatic vs. normative (LTO) component, often known as long-term orientation, refers to the degree to which individuals are required to explain perplexing current and future difficulties. Low LTO index cultures seek to hold to their traditions and are cautious about embracing social change (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Higher indices accept change and promote contemporary education as a method of preparing for the future. Singapore has a higher LTO index (72) than Hong Kong (61) (Hofstede-insights.com, 2022). Foreign businesspeople must consequently not sell themselves to be viewed seriously and be less likely to compromise because this is regarded as a weakness.

Indulgence vs. Restraint

Indulgent societies provide emotional fulfillment of human desires to enjoy life and have fun. On the other hand, restrained cultures repress gratification and manage it by stringent social rules (Gallego-Álvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2021). Singapore has more indulgence vs. restraint dimension (46) than Hong Kong (17). As a result, Hong Kong businesspeople who want to succeed in Singapore should respect arguments during meeting decision-making procedures.

In conclusion, the business cultures of Singapore and Hong Kong differ somewhat. A corporation must understand a host country’s culture and change its operations accordingly. Similarly, the organization must understand the cultures of both the home and host countries to establish appropriate strategies that promote long-term success.

According to the Hofstede cultural dimension, both countries exhibit low individuality and uncertainty avoidance levels. Some prominent variations worth noting are the power gap, masculinity, and long-term orientation, all of which differ significantly between the host and home nations. Since a corporation cannot alter the national culture of the host country it is critical for the firm and its management to devise ways to align its operations with its prevalent national culture. If the company intends to deploy professionals from its home nation to work in the new branch, they should be instructed on how to properly conduct themselves.

References

Abbass, K., Song, H., Mushtaq, Z., & Khan, F. (2022). Does technology innovation matter for environmental pollution? Testing the pollution halo/haven hypothesis for Asian countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(59), 89753-89771. Web.

Baker, J. (2020). Crossroads: Popular History of Malaysia and Singapore. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd.

Contractor, F. J., Dangol, R., Nuruzzaman, N., & Raghunath, S. (2020). How do country regulations and business environment impact foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows?International Business Review, 29(2), 101640. Web.

Chiu, S. W., Ho, K. C., & Lui, T. L. (2019). City-states in the global economy: Industrial Restructuring in Hong Kong and Singapore. Routledge.

Double-tax agreements in Singapore: Complete guide: Acclime. Acclime Singapore. (2021). Web.

Gallego-Álvarez, I., & Pucheta-Martínez, M. C. (2021). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and R&D intensity as an innovation strategy: A view from different institutional contexts. Eurasian Business Review, 11(2), 191-220. Web.

Hofstede-insights.com. (2022). Compare Countries. Web.

Lim, C. (2021). O Singapore! Stories in celebration. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd.

McGee, T. (2019). Urbanization in an era of volatile globalization: Policy problematics for the 21st century. In East-West Perspectives on 21st Century Urban Development (pp. 37-52). Routledge. Web.

McCutcheon, R. T. (2018). Studying religion: An introduction. Routledge. Web.

Tay, D. (2019). Death in a multicultural society: Metaphor, language and religion in Singapore obituaries. Cognitive Linguistic Studies, 6(1), 84-102. Web.

Vives, X. (2019). Digital disruption in banking. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 11, 243-272. Web.

Wang, Z., & Yang, L. (2022). Multilingual Singapore: language policies and linguistic realities: edited by Ritu Jain, Abingdon and New York, Routledge, 2021. Web.

Yeo, S. L., & Pang, A. (2017). Asian multiculturalism in communication: Impact of culture in the practice of public relations in Singapore. Public Relations Review, 43(1), 112-122. Web.