Abstract

This paper takes a critical look at market efficiency as well as the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). The three forms of market efficiency are defined and illustrated while a correlation of the three forms of market efficiency proportionate to analysis is also identified and discussed.

Effective market hypothesis is further discussed and illustrated and academic evidence regarding the different stands and viewpoints on market efficiency is examined. In addition, different financial analyst’s explanation in relation to the role and impact of an investor in the financial market is examined and discussed.

The prices of shares are also discussed together with the elements in the market that greatly influence the prices of shares and securities in general. The stability of various stock indices is also looked at and relevant factors that contribute to the alteration of the indices either through speculation or economics are discussed from different analytical perspectives.

Finally, examples of market inconsistencies are discussed in order to identify instances where the share prices of particular firms have deviated greatly from the standard equilibrium. The paper goes ahead and further identifies and discusses the prevailing circumstances that led to the abnormal deviation of share prices and the subsequent corrective measures taken.

Introduction

In order to be in a position to discuss the three forms of market efficiency, it is very important to comprehend the fundamental nature of market efficiency which is usually a major component of capital market efficiency. By definition, market efficiency is the level at which the present value of a given asset correctly replicates the existing information of the asset in the market place (Taleb, 2008).

Market efficiency necessitates a well organized capital market given that it is in such a market that new information on an asset is rapidly and accurately reflected in share prices and the current price is an objective estimate of its accurate economic value based on the revealed data.

Efficient Market Hypothesis on the other hand requires that all relevant information is in total and instantaneously mirrored in an asset’s market price, therefore presupposing that an investor will acquire an equilibrium rate of return (Shiller, 2003). An investor should therefore anticipate generating a standard return through the application of both technical analysis and fundamental analysis.

The three forms of market efficiency

Three forms of efficiency have been identified and grouped according to the nature of information which is replicated in prices.

Weak-form efficiency

This efficiency means the information contained in historic price action of a share can be recognized in the current share prices though analyzing the historic prices has no predictive effect on the future prices since different information will be released in the future.

A number of varieties of fundamental analysis techniques are apt to offer surplus returns in Weak-form efficiency, whereas most technical analysis systems will fail in this form of efficiency or intermittently produce surplus returns (Keynes, 1936).

This is largely owing to the fact that the historical share prices in addition to other historical data cannot be utilized for an extended period of time in investment strategies to make surplus returns. Share prices have no price patterns that can assist in the assessment of current prices and hence lack serial dependencies.

Future price movements are for that reason determined entirely by the information disclosed at that particular time which is not currently enclosed in the price series (Fama, 1998). The history of share prices can therefore not be studied so as to forecast the future in any unusually gainful approach. Serial correlation in daily stock returns is close to zero as shown in the table below

Table 1. Serial Correlation of Daily Returns on Eight Stock Markets

Source: Solnik, B. A Note on the Validity of the Random Walk for European Stock Prices. Journal of Finance (December, 1973).

Semi-strong-form efficiency

Entails that share prices fully and rapidly mirror all the major publicly available information in a neutral manner thus investors cannot earn excess returns through the trading on that information (Fama & French, 1988).

Neither fundamental analysis nor technical analysis systems are capable of consistently generating surplus returns in a semi-strong-form efficiency since information such as dividend announcements, rights issues and change of leadership among others is relevant as past price movements.

Furthermore, the market absorbs the publicly obtainable information after it has been exposed into the price and therefore nether technical or fundamental analysis will generate profit (Summers, 1986).

Strong-form efficiency

Share prices in this efficiency are dependent on all applicable information in spite of whether the information is for public or confidential scrutiny. Insider trading is a major factor in strong-form efficiency, since a small number of fortunate individuals for instance the directors of a company take up certain market positions in the trade of shares, since they are privy to private information that the normal investor is unaware of in the market (Taleb, 2008).

However, there are cases where private information cannot be publicized such as legal barriers that deal with insider dealing laws where strong-form efficiency is rendered unachievable (Keynes, 1936). According to Kleinberg & Tardos (2005), market where investors cannot always make surfeit profits over a long period of time needs to exist in order to activate strong-form efficiency.

Stock markets are as a result not a strong form of efficiency since it is likely for an investor to make unusual profits through the trading of shares through the analysis of confidential information that is not yet released or restricted from the public domain (Malkiel, 2003a).

Table 2. Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR) of Insider Trading

Source: Meulbroek, L. An Empirical Analysis of Illegal Insider Trading. Journal of Finance (December, 1992).

Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) states that the price of an asset mirrors every existing relatable information about the inherent value of the asset and any emerging information is included into the share value rapidly and plausibly with indication to the movement of the share price and the size of that movement (Fama & French, 1988).

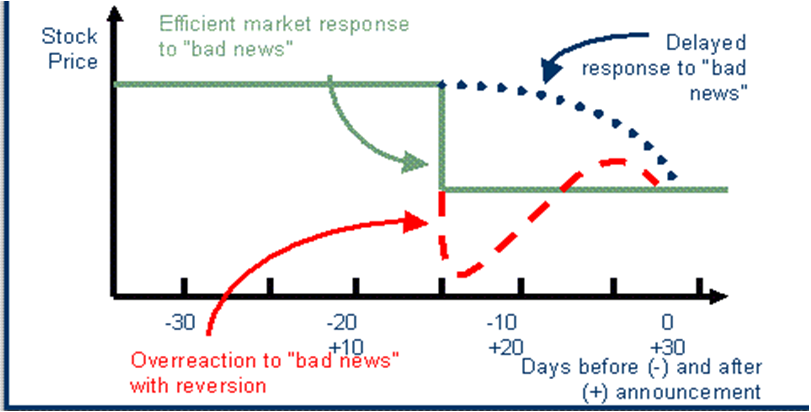

Graph 1. Reaction of stock prices to new information in efficient and inefficient markets

Source: Fama, Eugene F. Market Efficiency, Long-Term Returns, and Behavioral Finance. Journal of Financial Economics (March, 1998).

Investors in an efficient market are as a rule presented with opportunities for making returns on a share or security that are equal or less than the reasonable returns for the risk associated with that share or security (Kendall, 1953, p.14).

The lack of anomalous profit potential occurs due to the fact that the existing and precedent data is instantaneously revealed in current prices therefore making new information the only determinant which cause prices to change.

Forces of supply and demand are primarily responsible for setting the global prices in the major stock markets but hypothetically, investors are prompted to trade by the persistence of underrated and overvalued stocks which present profit opportunities (DeBondt & Richard, 1985, p.798).

The consequence of investor trading is the progression of stock prices in the direction of the present price of future cash flows. Analysts are principally in charge for spotting mispriced stocks and the consecutive trading of these stocks create an environment that makes the market competent and make prices to disclose central values (Samuelson, 1965).

Therefore, in an efficient market, fluctuation of stock prices should be unsystematic since new information is arbitrarily favorable or unfavorable depending on the expectations (Kleinberg& Tardos, 2005).

Literature Review

Eugene Fama (1991) associates market efficiency with a continuum where a more efficient market is determined by the lower transaction costs in that market. For instance, accurate information about firms in the United States is relatively cheap to obtain and thus trading in securities is considered to be relatively inexpensive consequently making the U.S. security markets to be viewed as relatively efficient.

The effectiveness of information in stock prices is vital to investors and firms because the different trading strategies investors use are all dependent on the information in order to generate excess returns (Grossman&. Stiglitz, 1980). Furthermore according to Malkiel (2003b), new investment capital is effectively utilized by the firms when the stock prices correctly reveal all information.

The first thorough examination of stock market takings was conducted by Louis Bachelier in 1900 and with reference to his dissertation; current returns have no indication or effect on the magnitude of future returns. According to Kleinberg (2005), stock returns bore statistical independence which allowed the French mathematician to posit stock returns as an indiscriminate occurrence.

Louis Bachelier’s study was supported by John Burr Williams who asserts that stock prices are subject to economic fundamentals in his study of intrinsic value. The other viewpoint illustrated by John Maynard Keynes is that of speculation where stock analysts propose trade on the stocks which they think the majority of other analysts consider being the greatest.

Research by Keynes (1936) shows that stock prices are mainly influenced by speculation and economic fundamentals play a relatively minor role in altering the prices. Prices determined by speculation may ultimately meet the prices that would exist based on economic fundamentals in due course.

Kendall (1953) recorded statistical independence in weekly proceeds from a multiplicity of British stock indices in 1953. Harry Roberts (1959) established almost equivalent results from the Dow Jones Industrial Index ahead of Eugene Fama (1965) who offered ample substantiation of statistical independence in stock returns.

Fama (1998) also provide substantial attestation to support his hypothesis that the different techniques used in technical analysis has no prognostic clout. According to Samuelson (1965) and Mandelbrot (1966), current stock prices replicate the prospect of investors who hold all the available information and hence future price will only change if investors’ expectations change. In addition, such stock prices changes ought to be arbitrarily positive or negative on condition that investors’ prospects are impartial.

Investing in stocks is considered a fair game and therefore an investor requires some informational advantage so that he/she can be in a position to beat the market or profit consistently. Fama (1998) in his publication identified the three different forms of market efficiency which are the weak form, the semi-strong form, and the strong form (Malkiel, 2003a).

Empirical research carried out in the 1970s supported the continuation of semi-strong market competence with only slight discrepancies that is to say the small-firm effect and the January effect. These indiscretions revealed the inclination of small-capitalization stocks to build up uneven returns early in the year, particularly in January (Taleb, 2008).

Recent studies have revealed that the different inconsistencies are due to misspecification of the illustration of asset values before market frictions. For example, the small firm and January effects are at present generally viewed as disbursements essential to balance dealers in small stocks, which have a proclivity to be illiquid, for the most part of the commencement of the year (Summers, 1986).

Observations that the irregularities at times concerned underreaction and overreaction and as a result could be supposed as arbitrary phenomena that were often offset when diverse timeframes or analysis were applied (Samuelson, 1965).

A case identified by Robert Shiller (1981) argued that stock index returns are very unpredictable when compared with comprehensive dividends, which was evidently in support of Keynes’s study that stock prices are determined by speculators instead of fundamentals.

Readings by DeBondt and Richard (1985) offered new data that showed perceptible overreaction in specific stocks over extended periods of time that he referred to as reversion to the mean or mean reversion normally of 3 to 5 years.

The stocks prices that had performed rationally well over a 3 to 5 year period in particular were predisposed to regress to their averages through the subsequent 3 to 5 years that led to negative surplus profits (DeBondt& Richard, 1985, p.782).

Conversely, the prices of stocks that had performed fairly poor had a tendency to go back to their averages which led to positive excess returns. Summers (1986) illustrated that, prices could take lengthy, and slow deviations away from fundamentals that would be inconspicuous with short time frame returns.

Supplementary empirical data regarding mispricing according to Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) exposed a continued trending of stocks as long as the stocks grossed with elevated or low profits over 3 to 12 month durations.

The perceptible contradiction in returns ideology led to the materialization of a novel school of thought identified as behavioral finance that studies behavioral economics. Behavioral finance analysts oppose the hypothesis of rational prospect and derived their argument from the field of psychology asserting that individuals have a propensity to make systematic cognitive errors when structuring prospects (Malkiel, 2003b).

An example of systematic cognitive errors that may possibly explicate overreaction in stock prices is the proposition that traders endeavor to distinguish trends even in situations lacking trends and that assumption is capable of purporting the erroneous conviction that future patterns will be similar to patterns of the recent past (Fama, 1998, pg 289).

The drive in stock proceeds may also be elucidated through affixing with the partiality to center on preliminary beliefs and disregard the implication of new information.

Momentum studied over intermediary timeframes can be extrapolated over longer durations in anticipation of the development of overreaction. Fama and French (1988) provide opposition to the hypothesis that stock prices analytically overreact with their view that stocks gross better returns when economic conditions are more difficult, Capital is comparatively insufficient and even the normal risk payments are high relating to interest rates.

Pricey interest rates will at the outset push prices down but with enhanced business conditions; prices ultimately improve and for this reason comply with the average lapse pattern in aggregate returns(Grossman &. Stiglitz, 1980).

Furthermore, the cognitive failure of particular people would have a very small effect on stock markets in view of the fact that mispriced stocks ought to magnetize cogent investors who as a principle buy underpriced and sell overpriced stocks (Roberts, 1959, p.15).

Poterba and Summers (1987) responding to the data presented by Fama and French disputed that the standard lapse model in complete indicator profits is very irregular to be elucidated using just recurring economic circumstances.

Poterba and Summers (1987) maintain that disproportionate mean reversion was caused by the divergence of prices from fundamentals, hence supporting Shiller’s excess volatility theory.

Moreover, Shleifer and Robert (2003) observed that mispricing can continue since it presents a small number of opportunities for low-risk arbitrage trading considering market efficiency demands that traders acquire and translate information fast due to fear of losing their lead in timing.

The most prominent paradigms of perceptible variations are the stock market crash that took place in 1987 along with the progress of stock prices starting in the final parts of the 1990s.

Mitchell and Netter (1989) perceived that the sudden colossal market decline days prior to the 1987 market crash was caused by a primarily normal reaction to an unexpected tax proposal, which sequentially set off a transient liquidity crisis owing to increased sales volumes which exceeded the market’s buffer capacity.

The constructive market environment for technology stocks in the late 1990s exemplifies the stock market’s significant position in resource distribution. Conducive conditions also facilitate privately owned firms with the opportunity to increase funds using an initial public offering (IPO) of stock (Mitchell & Netter, 1989).

Any firm whose stock has swiftly increased in value raises supplementary funds more easily by using a secondary offering since elevated prices signifies a lesser proportion of the firm’s ownership is to be offered to acquire a specified sum of capital (DeBondt& Richard, 1985).

In addition, a new and attractive IPO market draws organizational investors and investment companies which inject funds in industries and sectors with the intention of developing the sector then selling their shares for profit. Such positive market surroundings are considered to be dependable and are viewed as the rousing support formulating the fund-pooling division of venture growth (Mitchell & Netter, 1989).

The technology and Internet-based stocks market seems to have worked up investor appetite in the late 1990s and through retrospection channeled surplus investment capital toward the sector (Roberts, 1959, p.24).

Favorable market conditions in a new industry can draw the investment capital; the returns an investor in the technology and Internet-based division could have understandably projected had plummeted lower than what economic conditions could substantiate, and below what most investors essentially expected (Shiller, 2003).

Conclusion

Although stock value prices may at times have divergences from fundamentals, the EMH is helpful over short timeframes where it can be employed to clarify the movement of stock price alterations. The stock prices react to new information plausibly the same way as the variation as in the basic value of equity. EMH also acts as a standard reference point as to how prices should be executed if finances and supplementary resources are to be distributed competently.

The simplicity of information, the usefulness of instructions as well as the prospect that cogent arbitragers are key determinants of the standard the markets set with reference to the EMH benchmark. It has also been documented that a high intensity of market competence is delimited by random circumstances that prevent the gainful opportunities.

Consequently, the costs of analysis and trading together with organizational costs are largely accountable for discouraging market efficiency. Different markets result to adopting different echelons of market efficiency mainly because of the costs associated with analysis and operation in the diverse markets and countries.

References

DeBondt, F. M., & Richard, T., (1985) Does the Stock Market Overreact? Journal of Finance, 40 (4), pp.793–805.

Fama, E., F., (1998) Market Efficiency, Long-Term Returns, and Behavioral Finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 49(3), pp.283–306.

Fama, E. F., & French K. R., (1988) Dividend Yields and Expected Stock Returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 22 (3), pp.3–25.

Grossman, S. J., &. Stiglitz J.E., (1980) On the Impossibility of Informationally Efficient Markets. American Economic Review, 70 (6), pp. 393–408.

Jegadeesh, N., & Titman S., (1993) Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency. Journal of Finance, 48 (3), pp. 65–91.

Kendall, M., (1953) The Analysis of Economic Time Series, Part I: Prices. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 96 (5), pp. 11–25.

Keynes, M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. 2nd ed. New York: Harcourt.

Kleinberg, J., & Tardos, E., (2005) Algorithm Design. 3rd ed. London: Addison Wesley

Malkiel, G., (2003a) The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17 (1), pp. 59–82.

Malkiel, G., (2003b) A Random Walk down Wall Street. 8th ed. New York: Norton.

Mandelbrot, B., (1966) Forecasts of Future Prices, Unbiased Markets and ‘Martingale Models. Journal of Business, special supplement, 12 (1), pp. 242–255.

Mitchell, M., & Netter, J. (1989) Triggering the 1987 Stock Market Crash: Antitakeover Provisions in the Proposed House Ways and Means Tax Bill? Journal of Financial Economics, 24 (9), pp. 37–68.

Poterba, James M., & Summers, L., (1987) Mean Reversion in Stock Market Prices: Evidence and Implications. Journal of Financial Economics, 22 (7), pp. 27–59.

Roberts, H., (1959) Stock Market ‘Patterns’ and Financial Analysis: Methodological Suggestions. Journal of Finance, 14 (6), pp. 11–25.

Samuelson, P., (1965) Proof that Properly Anticipated Prices Fluctuate Randomly. Industrial Management Review, 6 (8), pp. 49.

Shiller, J. (2003) From Efficient Markets to Behavioral Finance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17 (1), pp. 83–104.

Summers, L., (1986) Does the Stock Market Rationally Reflect Fundamental Values? Journal of Finance, 41 (7), pp. 591–601.

Taleb, N., (2008) Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets. 2nd ed. New York: Random House.