Introduction

Market failure in some industries is caused by complex political, economic and social factors that affected an industry. The theoretical models provide numerous lessons about the macroeconomic effects of global changes and their impact on a particular market. To the extent that the higher current account deficits and surpluses matching increased capital flows reflect differences between domestic investment over domestic saving, the external balances themselves should not be considered problematic, in and of themselves (Cowen 1988). The main causes of market failure involve:

- Externalities,

- Public goods,

- Information asymmetries,

- Natural monopolies or decreasing cost industries.

Each of these reasons has a separate impact on industry and market and is involved in complex global processes that affected the external environment of every industry.

Externalities and Market Failure

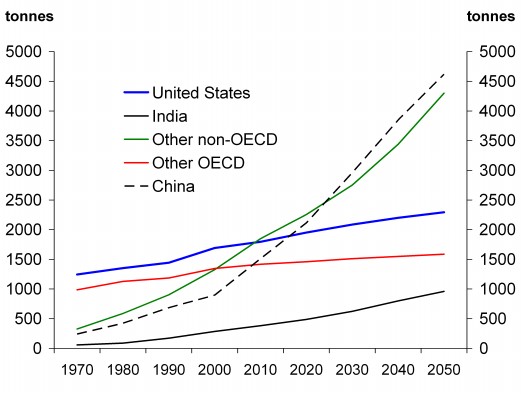

Externalities can be explained as tangible units which are not charged for in the price system. The growth of industries and cities placed a tremendous burden on the environment by introducing pollutants such as pesticides, radioactive isotopes, and heavy metals into the air, land, and water. There are now approximately seventy thousand different chemicals in the marketplace, and new ones are being produced at an accelerating rate. In addition, the use of precious supplies of energy and materials for luxuries such as motorboats, air conditioners, and hair dryers has added more stress to the environment (The Stern Report 2008). These items deplete limited resources of raw materials necessary to make such products, as well as the depletion of “clean air” in the environment. The use of natural resources at a rate higher than nature’s capacity to restore itself will result in the pollution of air, water, and land. from the standpoint of the environmental crisis. This has a direct impact on the market performance of companies and their profitability (Mankiw 2006). The Kyoto protocol prevents many industries to compete and demanding further changes, The transboundary movements of pollutants lead to unusual and complex economic and political difficulties. Individuals in one nation may suffer economic loss and health hazards as a result of the pollution that originated in another nation, yet they may not benefit from the economic activity that caused the pollution (Pindyck and Rubinfeld 2000). On the other hand, a nation or jurisdiction that acts to minimize pollution that is being transported over hundreds of miles may gain little local environmental benefit. Externalities led to market failure in pharmaceutical and chemical industries depended upon regulations but dumped tons of toxic waste into the air. The effects of pollutants can be immediate (acute toxicity). The case of the pharmaceutical industry vividly portrays possible life-threatening effects that come from toxic pollutants and ineffective waste management. The toxic effect is produced by exposure of a continuing and prolonged nature. Of concern are delayed toxic reactions, progressive degenerative tissue damage, reproductive toxicity, cancer, mutations, and various other problems (Stiglitz 2001).

Toxic wastes dumped by pharmaceutical plants result in desertification which could also seriously decrease the carrying capacity of the and lands that support human settlements and wildlife. Desertification is the process of productive environments becoming increasingly desertlike. It is characterized by the lowering of water tables, a shortage of surface water, the salinization of existing water supplies, and wind and water erosion. In arid and semiarid regions the main cause of desertification is the overuse of land, resulting from overgrazing, over-drafting (mining) of groundwater for agriculture, poorly managed irrigation, the use of soils with poor drainage, and the choosing of crops and employment of agricultural practices that neglect soil conservation. Their only option is to overharvest arid and semiarid areas for fuel and food. This is caused by the scarcity of suitable land and capital, which are essential to providing for their families. The concern for protecting these vulnerable areas, although they will not be affected for a decade or two, appears understandably small to these peasants compared with the value of feeding their families today; therefore, conservation is left to be a concern only for those few altruistic individuals who are not starving (Winston 2006).

Public Goods

The main problem of public goods is that they are non-rival and non-excludable goods. Global public goods are international financial stability, environmental sustainability and infectious disease control (Cowen and Crampton 2002). In contrast, the present framework is comprised of numerous supranational economic institutions, such as the Bank for International Settlements, the World Trade Organisation, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other United Nations-affiliated bodies. Generally speaking, these institutions advocate compatible, pro-globalization objectives. Indeed, a major rationale for these organisations, most of which under one guise or another has been operating for over half a century, is to encourage and facilitate increased global exchange (Mankiw 2006). Yet, further scope remains for integrating international goods, services and asset markets. For instance, trade-to-GDP ratios is still relatively small for many economies in the world, including large economies like the United States and Japan. Moreover, most of the investment that occurs in national economies is still funded by domestically generated savings, suggesting considerable potential remains for exploiting the gains from global finance (Winston 2006).

The pharmaceutical industry creates new demands and shifts public goods to the global market. Several factors stimulate acceptance of the marketing philosophy (Mankiw 2006). It supports AIDS programs and disease prevention around the globe. Among them are these: (1) increased production capabilities in an economy of abundance, coupled with a lack of ready-made markets to consume the goods and services produced; (2) keenly competitive conditions that force greater attention on consumers and consumption; (3) the “profit squeeze” resulting from increased costs and competitive prices, which narrow profit margins; (4) the automation of manufacturing systems which, bringing high fixed costs and continuous production capability, require mass markets to spread them; (5) the recognition of the role of innovation and the contribution of new products to corporate growth and survival; (6) the growth of mergers and multinational corporations that recognize the need for better market planning and coordination; and (7) the development of mass markets with widespread discretionary spending power, thereby providing an opportunity for developing new products to meet consumer wants and needs (Cowen and Crampton 2002).

Natural Monopoly

A monopoly must depend upon some difficulty, either natural or artificial, which stands in the way of new firms entering a trade. In conditions of free entry, if demand increases, so that price exceeds the cost, abnormal profits are made and these abnormal profits will attract new firms into the industry until profits are again reduced to the normal level (Mankiw 2006). Monopoly profits can only continue to be made if for some reason they do not succeed in attracting new capital into the industry. With the nature of these obstacles, we are not here concerned. But it may well happen that though new firms which come in cannot at once secure the custom of all purchasers who are paying prices above those at which they are able to sell similar goods, they can obtain the custom of some of these. In this case, new firms will enter the industry, so soon as the increase of demand is sufficient to attract them, and we must make allowances for this in our calculations (Cowen and Crampton 2002). Natural monopoly involves decreasing the cost of the entire output range. The pharmaceutical industry establishes a monopoly on some drugs certified by FDA. This industry will be in equilibrium if at the ruling price, there is a tendency neither for the total of the industry’s output to be expanded nor to be contracted. But any expansion may be the consequence either of an increase of output by existing firms, or of an addition to the number of firms, or of both (Mankiw 2006). The conditions of equilibrium must therefore be two. First, that each firm shall be in such equilibrium that it shall have no tendency to expand its output. Second that the firms shall be making only such profits that the number of firms in the industry will remain constant. The firm, we have seen already, is in equilibrium when marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. At that point, neither expansion nor contraction can increase its profits. The industry is in equilibrium when firms are making such profits that there is no incentive to alter. The case of the electricity market shows that this situation can lead to market failure and breakdown (Cowen 1988).

Now it is obvious that it may well happen that marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost, but that price is greater than average cost. This in fact is the normal condition of the monopolist (Mankiw 2006). New firms, we have seen, will come in, if they are free to do so. The effect of the new firms coming in is to change the amount demanded from each of the old firms at any given price, and probably also the elasticity of demand. This change in the conditions of demand for the individual firms will alter the marginal revenue of the firm and will destroy the equilibrium between marginal revenue and marginal cost (Cowen and Crampton 2002). The firm will proceed to adjust its output to the new conditions as successive new firms enter the trade so that at each point marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost, but the consequent profits will gradually fall and it will gradually achieve the double condition of equilibrium (Pindyck and Rubinfeld 2000).

Information Asymmetries

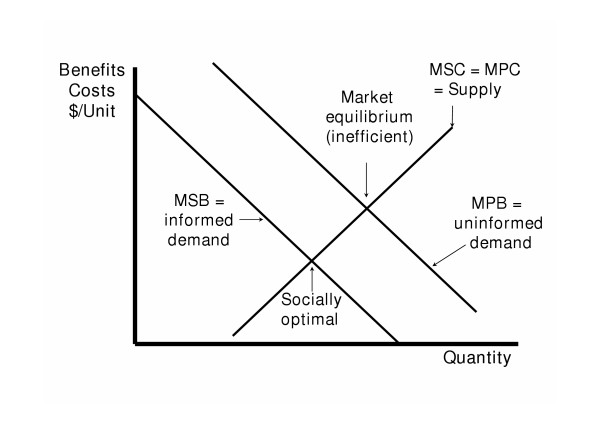

Information asymmetries are often cited as the main reason for market failure. The main problem for marketers is that they take into account advantages and opportunities proposed by the industry but do not take attention to disadvantages and threats. Adverse selection and market signalling, moral hazard and principal-agent problems lead to market asymmetry (Mankiw 2006). For the pharmaceutical industry, often the assessment of market opportunity is achieved through test markets. Yet this can be a hazardous route. The selection of test areas representative of future markets and the development of a normal marketing environment are difficult to achieve (Cowen and Crampton 2002). Though testing fundamentally new products are complicated, tests do provide much valuable information about product acceptance and the effectiveness of alternative strategies. Simulation is a mathematical technique that companies may find useful in assessing the market opportunities. It can provide a means for testing the profitability of available alternatives, thereby providing insight into future operations. The assessment of market opportunity emphasizes that business ventures begin with a study of the market, that the future of the business rather than it’s present or past is the most significant dimension, and that every company must commit itself to change and innovation (Winston 2006). Continuous assessment stresses that management does not focus on products or processes that it now possesses (Cowen 1988). Rather, management becomes concerned with satisfying changing consumer wants and needs and continuously adjusting company resources to that end. This necessitates translating the sales forecast into a specific market, customer, product, territory, and volume goals to be realized during some future period. Thus, the sales forecast becomes the foundation for marketing programs, financial budgets, purchasing plans, personnel budgets, production schedules, plant and equipment demands, expansion programs, and other aspects of management programming (Mankiw 2006).

Conclusion

That is a question regarding which the economist will inevitably have views, but on which he has no more claim to the final word than have other experts in politics, in ethics, or in religion. The industry can usefully produce for consideration the arguments which may be employed to support or to deny the claims of market failures to improve the efficiency of the economic system regarded, first, as a means of organizing the technical production of material goods, second, as a means of securing that those goods are produced in the amounts that are desirable, third, as a means of distributing to individuals the incomes which it is proper that they should enjoy. The case of pharmaceutical inductees shows that international financial flows accompanying financial globalization can change current account imbalances, interest rates, exchange rates, national expenditure, output, employment and inflation in host economies.

Bibliography

Cowen, T. The Theory of Market Failure: A Critical Examination. George Mason Univ Pr, 1988.

Cowen, T., Crampton, E. Market Failure or Success: The New Debate. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, 2002.

Mankiw, M.G. Worth Publishers; Sixth Edition edition, 2006.

Pindyck, R. S. Rubinfeld, D. L. Microeconomics. Prentice Hall; 5th edition, 2000.

The Stern Report: 2008. Web.

Stiglitz, O. Climate Change. 2001. Web.

Winston, C. Government Failure versus Market Failure: Microeconomic Policy Research And Government Performance. Brookings Institution Press, 2006.