Abstract

The power of the media in shaping our societal beliefs, values and attitudes is undisputed. Behind this power is a team of media practitioners who shape the structure and understanding of everyday broadcasts. Based on a background of information and communications technology, this paper demonstrates that media operatives are today’s modern architects in facilitating cultural exchange. Evidence is gathered from different countries and the operations of state, global and digital media centres. The impact of these media centres is analyzed to evaluate how they facilitate cultural exchange in present-day society. This paper posits that media operatives have given us the freedom to freely express ourselves, thereby facilitating cultural exchange throughout the world. In addition, through such freedoms, we have been able to challenge different prevailing attitudes and assumptions regarding different social, economic and political issues in our societies. Comprehensively, this paper proposes that media operatives have altered the structure of present-day broadcasts to facilitate an intercultural agenda, but with the advent of social media and the spread of the internet, this paper suggests that we should change our idea of media operatives to include digital media pioneers as a very influential media group as well. Indeed, media operatives are modern architects in our understanding of intercultural dialogue.

Introduction

Statement of the Problem

Over the years, intercultural understanding has improved. However, the world is still a long way from being completely cohesive. Globalization has played an important role in tolerating intercultural understanding because today, people find it more useful to learn other people’s cultures, language and customs for business advantage or economic stewardship. For example, current management literatures emphasize the importance of learning and appreciating new cultures as a tenet of modern managerial curriculum. Citizens in developed countries are also more willing now to learn (at least) a second language while foreigners are equally willing to learn new cultures to facilitate daily activities. The Spanish language for example is well celebrated in the United States (U.S) and it is currently the second most spoken language after English (Ardila and Ramos 2007, p. 12).

Apart from globalization, the advent of the information age has precipitated the interaction of different cultures at a level which has never been witnessed before. These interactions have surpassed geographic, national and cultural boundaries. For example, Howard and Idriss (2012) explain that

“Immigrants to Europe and the United States comprise a growing portion of the populations in those regions, their customs and cultures mixing with the hybrid American and European cultures to create results unique from that found in either their country of origin or their newly adopted home-countries” (p. 25).

The cultural interactions within the European continent are just a shadow of the level of intercultural exchanges going on in the world today. Part of this trend has been facilitated by globalization which has not only facilitated cultural exchange but also practically made cultural commodities available throughout the world. This situation has especially been facilitated by the growing prominence of cultural industries which are mainly found in western economies. From this trend, many people have become more mixed, interrelated and interconnected like never before. The level of cultural intermix can equally be compared to the level of cultural dispersion seen within the society today.

As will be explained in subsequent sections of this paper, the high level of cultural exchanges we witness today is courtesy of the present-day marketplace which is also facilitated by a highly commercialized telecommunications and media industry (Howard and Idriss 2012). These intercultural exchanges constitute part of the debate regarding the drawbacks and benefits of a globalized society. Part of the drawbacks (reported to constitute the idea of a global village) is the inequality that intercultural exchanges brings. In other words, the benefits of intercultural exchange are reported to be unequal across different cultural divides (Howard and Idriss 2012). This phenomenon will be further investigated in subsequent sections of this study.

Abstractly, cultural exchange is observed to benefit culturally superior groups while countries which have culturally inferior groups tend to be the biggest losers in this equation. Such inequalities are normally witnessed in a market system where cultural exchanges limit the dispersion of cultural characteristics. Therefore, the benefits of cultural exchanges tend to concentrate on cultural forms that are most profitable but unfortunately, not to those cultures that represent the best values or majority views in the society. For example, American pop culture often tends to reinforce negative American stereotypes that portray Americans as sexually-obsessed, greedy, selfish, superficial and ignorant (Rehman 2011, p. 1). Furthermore, the portrayal of other cultures within these American cultural inferences tends to be unflattering because of the negative portrayal of other cultures in the American media. Rehman (2011) explains that such cultural inferences may do more harm than good by increasing cross-cultural differences as opposed to merging the cross cultural gap within different communities. This view will be further investigated in subsequent sections of this paper but it is equally interesting to note that the same people who criticize the media for the lack of amelioration are the same ones who constitute the market for such divisive media content.

Seamless intercultural communication has however not always been the dominant philosophy. In the recent past, intercultural communication was frowned upon because it was perceived to be a way to neutralize dominant cultures (Rehman 2011). There was therefore a lot of resistance from proponents of dominant cultures who practiced self-preservation by shunning other cultures. History documents gruesome accounts of massive killings and discrimination that occurred (merely) because people had a different skin colour or did not subscribe to the dominant culture. Episodes in modern history are littered with evidence of extremism such as the Hitler rule in Europe where thousands of people were killed because they did not subscribe to the dominant culture. Massacres and genocides are also well documented in historical books throughout the world, including Africa, where millions of people were killed in Rwanda merely because they hailed from a different tribe. Nonetheless, over the years, this situation has changed and the world has come to appreciate the diversity among different cultural groups.

Somewhat, there has been a consistent tolerance of intercultural dynamics not only in the business environment but also within social, economic and political spheres (Rehman 2011). Intercultural competence is therefore stronger today than in the past. More importantly, it is correct to say that people today are more versant with culture-specific concepts that are familiar with perceptions, thoughts, feelings and attitudes of foreign cultures. Indeed, many people today are freeing themselves from prejudices and stereotypes which have historically characterized intercultural communication. Many more people are now willing to learn new cultures

However, with this new appreciation of new cultures comes a very minimal understanding of the forces or structures that have promoted intercultural understanding. Current literatures focus on traditional interactive media such as tourism, marriage, colonialism and other practices as some of the main factors which have led to the relative tolerance of intercultural dynamics. However, few literatures encompass the new dynamics of telecommunication and its antecedents in promoting cultural exchange. This paper demonstrates that the media has been overlooked as a primary force that has prompted an intercultural world. This argument centres on depicting media workers as modern architects of intercultural exchange.

Purpose of the Study

“It is time to recognize that the true tutors of our children are no longer the school teachers and university professors, but the filmmakers, advertising executives and pop culture purveyors” (Howard and Idriss 2012, p. 1). This statement was made in an article analyzing the role of the media in shaping the beliefs and values of children today. It is no secret that today; technology has taken over most aspects of our lives. However, there is no better way to demonstrate the power of technology than through its influence on the media. Most of the opinions and views we hold today are shaped by the media, and if this is not the case, the media has played host to our social debates, thereby influencing our perceptions. This trend has not only been witnessed in the developed world because the heightened media attention in the developing world is also a product of the media revolution we witness in today’s global society (Howard and Idriss 2012).

Indeed, global news agencies like Cable News Network (CNN) and British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) have fuelled the ever-expanding dominance of mainstream media on the globe while Arab new agencies like Aljazeera and Al Arabiya have fuelled the same trend in the Arab world. The fast-expanding media space has largely been fuelled by the growth of the internet with global audiences now forming part of a new media dominance that is like nothing before. Partly, we can say that today’s global media has created a new political schooling that is shaping opinions all across the world (Howard and Idriss 2012). This progress has acted as a platform to challenge past ideas and philosophies because now, across the globe, people do not simply hold intellectual beliefs about other people in distant lands; instead, they hold strong reservations about some of the opinions that are being expressed in the media.

For example, there has been a deep debate about the clash of civilizations which has quickly spilled over from mainstream media to other forms of communication (Howard and Idriss 2012). This debate has especially been explosive on two fronts: the western philosophy of civilization and the Arab idea of the same. Mostly, the western culture has portrayed in bad light the Arab cultural progression by focusing on sensitive topics such as religion (Islam) and how the Arabic culture oppresses its people (like women). Defensively, Arabs have come out against western ideologies and defended their culture in emotional and somewhat demeaning rhetoric. However, the tilt has been balanced because some Arab new agencies have sometimes made a mockery of western culture in entertainment shows and similar platforms while western media has not shied away from the same treatment (Howard and Idriss 2012). These back-and-forth exchanges have been emotive (to say the least) but they represent the strength of the media in progressively advancing an inter-cultural agenda (or retrogressively doing the same).

Apart from the negative media exchanges that characterize a split society, the potential of the media to encourage global awareness is unrivalled. For example, never in the history of the world have people been more tolerable, understanding and less critical of the cultural, ethnic, religious, gender and social differences existing in the world today. Largely, the media has played a huge role in this social advancement. Unfortunately, the contribution of the media is a double-faced sword because it can reinforce negative stereotypes like it can promote intercultural exchanges.

This paper paints a simplistic scenario where media workers have acted as modern architects to bridge the cultural divide that continues to narrow every day. Evidence will be sourced from state media broadcasts such as China Central Television (CCTV) in China to show the history and progress that has been made by state media houses in intercultural exchange. In addition, this paper will also analyze the role that global media has played in fostering cultural exchange. Finally, as a complementary tool for understanding the research topic, other media platforms such as social media and blogs will be analyzed to demonstrate the extent that technology has impacted intercultural understanding in the world today. The focus on global media houses and auxiliary media platforms are only supplementary analyses to show the role that state media companies have played to facilitate intercultural understanding. Comprehensively, these analyses will show that state media workers have played a huge role in facilitating inter-cultural exchanges in the world today. The research objectives for this paper are as follows:

Research Objectives

- To investigate what media platforms are most effective in fostering cultural exchange

- To establish what roles governments have played in enabling cultural exchange through the media

- To find out what impact the digital revolution has had on state media and its effectiveness in facilitating cultural exchange

- To evaluate whether the media has played a balanced role in cultural exchange

Importance of the Study

“Why should we strive for global understanding?” (Rehman 2011, p. 1).This is a question that has often been neglected in the study of cross cultural communication. For many people, this question may seem absurd, but to others, this question directs most of the debates we have about intercultural communication. Abstractly, global understanding forms the framework for understanding intercultural communication, and by extension, it explains some of the most deeply-entrenched social, political and economic problems we face today. Rehman (2011) explains that the importance of global understanding can be summed into two categories: political conflict and international trade.

Before we dig deep into the intricacies of this study, it is important to point out that the purpose of this study will mainly be centred on these two concepts – international trade and the avoidance of political conflict. Political conflicts usually stem from philosophical conflicts which are also birthed from economic gaps that exist between countries or different parties within the community (or any other social context) (Rehman 2011, p. 1). Historically, countries have gone to war because of religious differences and other philosophical differences. This reason still hold true in today’s modern society but it also explains some of the world’s worst conflicts such as the First World War, the Second World War and the cold war. History shows us that, followers of Christ have fought with non-believers and Christians have equally fought with Muslims (Rehman 2011, p. 1).

Such religious conflicts continue today. For example, the war on terrorism has taken a perfectly religious undertone where protagonists claim that extremist religious groups are funding terror organization across the globe to wage a religious war mainly against western countries and their allies. However, some of these wars have purely been based on religious domination. For example, the religious war in Nigeria is fought by extremist Islamic groups which want to impose Sharia law in Northern Nigeria. The same war has been witnessed in Somalia and other parts of Africa. Israel is also victim to such religious wars because it is surrounded by hostile Muslim nations who are determined to ‘finish’ the nation (Howard and Idriss 2012). The disagreement between capitalist nations and communist nations has also exposed the differences in ideology among major world powers. Unsurprisingly, dominant world powers like China have historically differed with their western counterparts on important international issues because of their ideological differences. Most of the world’s major conflicts have therefore been fought along philosophical and ideological differences.

Perhaps it is human nature, but people have been slow to learn that wars do not necessarily eliminate conflict. Similarly, wars do not solve grievances or ideological or cultural differences. For example, religious and philosophical differences are almost impossible to eliminate because they are deeply engrained and form part of different cultures and belief systems (Rehman 2011, p. 1). Due to the divisive nature of such philosophical and ideological differences, Rehman (2011) points out that the main solution to some of the world’s main conflicts lies in understanding one another. Regarding this assertion, Rehman (2011) explains that

“When two intelligent people with opposing ideologies agree to a dialogue,

they usually arrive at some understanding that enables them to exist side by

side. Such understandings are not attained overnight. They require patience,

persistence, and a willingness to give and take” (p. 3).

The end of the cold war and the arms reduction resolution between Russia and the U.S is one example of the importance of mutual understanding to solve conflicts. The creation of the European community market and the ongoing peace negotiations between Israel and its neighbours are also other examples showing the importance of resolving conflicts through mutual agreements (Rehman 2011, p. 1).

Apart from solving political conflicts, the findings of this study will also be important in understanding international trade. Albeit the dominance of stronger nations over weak nations still exists, there has been tremendous progress made to provide an equal play-field for countries to contribute in international trade (Rehman 2011, p. 1). For example, colonialism was an economic tool used by developed countries to take advantage of the weak but in present-day society, countries cannot invade other countries for economic domination because there will be widespread condemnation. Often, invading countries have a lot to lose when they invade other countries. Russia’s involvement in Afghanistan and the quest by Saddam Hussein to invade Kuwait proved disastrous for Russia and Iraq respectively because they experienced severe economic problems from the invasions. Rehman (2011) suggests that since conflict cannot be completely eradicated, creating new markets and supporting global trade is a viable solution to solving some of the most pertinent international conflicts. The link between international trade and this study stems from the fact that international trade includes the understanding of people’s language, culture and customs while this study investigates the facilitation of intercultural understanding through the media.

Comprehensively, the importance of this study is depicted through the use of intercultural understanding to solve of the inherent problems in world conflicts and international trade. Through the understanding of the role of the media as modern architects who promote intercultural exchanges, a new paradigm of intercultural understanding can be fostered to alleviate some of the world’s worst conflicts which are created from philosophical and ideological differences.

Literature Review

Rehman (2011) explains that when analyzing the role of media practitioners in facilitating intercultural exchange, it is important to acknowledge the different media dynamics in various parts of the world. Representatively, this chapter starts by analyzing the role of media practitioners from the Chinese, Arab, European and Jamaican perspectives

Country Analysis

Perspective from China

With the recent emergence of new world powers, the Chinese economy has seen a rapid expansion of its middle class. This expansion has led to the rise in household income and the subsequent expansion of income per capita. The literacy levels in the country have also risen in the same regard. In China, political activism played a big role in the rapid expansion of the country’s mass media (Blumler and Nossiter 1991; Kaufman 1966). Alongside the expansion of mass media, urbanization and the urban life have equally grown. Around the 70s, there was a developing trend where many civil society bodies were becoming liberalized, thereby improving the sensitization about having one state media to increase national unity (Blumler and Nossiter 1991). Around this time, there was also a lot of fuss about the politics of economic powers which greatly revolutionized the telecommunication industry (Blumler & Nossiter 1991). This development was witnessed because the telecommunications industry was perceived to be the hub of information and knowledge exchange. These two industries were equally perceived to be the tools of power (Li and Lee 2000).

Apart from the media industry, information technology advancements have also spurred tremendous growth in international communication. In the past, telecommunication advancements were mainly confined within person-to-person, business-to-business or government-to-government communications but recently, these advancements have stretched beyond these confines (Chan 2000). Particularly, the 20th century heralded a period of evolution for international communication because broadcasting technology and wireless communication were being entrenched in the telecommunication industry, thereby avoiding some of the disadvantages of broadcasting, such as, delayed relay of information for existing broadcasters. For instance, it is during the 20th century that communication satellites and fibre optic infrastructure were established to improve the global infrastructure of telecommunication and broadcasting (Gregory & Stuart 1999). Notable organizations that were spearheading the advancement and adoption of such technologies included International Telecommunication Union and Intelsat Beijing Broadcasting Institute Press (Huang 1994). Nonetheless, it is particularly important to highlight that people were the main pioneers behind this development and not the corporations they worked for.

In a book titled Information and World Communication, Wei (2000) explores how information flows in the global mass market by focusing on unique confines such as culture, law, economy, technology, politics (among others). In the same book, Wei (2000) explores how varied communication systems have impacted the global society and most importantly, what interests have arisen as a result. Nonetheless, Blumler and Nossiter (1991) point out that a significant proportion of the advancements that have occurred in the telecommunication sector have been birthed from inter-jurisdictional competition.

The advancements in telecommunication have taken different dimensions for most countries. In China, the onset of the new millennium heralded a phase of new structures and shapes for the Chinese media industry (Donald and Keane 2002). Economic concerns have been at the centre-stage for the re-organization of the Chinese media industry because the government’s motivation for allowing a structural change of the industry has largely been motivated by economic concerns (Weber 2002). The impact of these readjustments has been unparalleled in the way the Chinese television compares to the rest of the world. Ongoing developments in other communist states across the world have also had a strong impact on the progress of China’s media industry.

For example, the fall of the former Soviet Union catalyzed the progress of Chinese media from a dictatorial entity to an economically oiled industry (Wei 2000). Notably, the Chinese economy was highly influenced by government plans but as the revolution to a liberalized market took centre-stage, there have been many market-based influences on the economy. Consequently, the Chinese television industry has equally been market-based. However, this revolution has not been smooth. The history of Chinese television shows that market failures and the failure to keep up with technological changes have greatly affected the progress of the industry. As a result, the Chinese television industry failed to have a strong or notable impact on the market (Weber 2000). This development was a strong disappointment for the Chinese people because the television industry was trusted to spear-head economic reforms. In my opinion, this concern (of the Chinese people) emphasizes the importance of discovering the bridge between cross-national communications.

Littlejohn (1996) understands the world as a process by which things change within a given period. His analysis can be effectively used to describe the evolution of the Chinese television industry. Basically, the main forces that have revolutionized the Chinese television market have been pulling in opposite directions. Interestingly, these two forces have been merged to create a common position that in Littlejohn’s understanding is the creation of a process dialect (Littlejohn 1996). Practically, this process dialect can be understood by the quest for Chinese television to accommodate the varied economic and other socio-political dynamics (Miller 2003; Atkinson1995).

For a long time, China has struggled to merge its history with its cultural identity and through such efforts; the company has been able to interact effectively with information markets around the world through the redesign of its television market (Kaufman 1966). Through this redesign, the Chinese television industry has refocused the attention of its television programming to economic and trade matters. In the interpretation of the Chinese television industry, this revolution can be termed as market socialism. In line with this vision, China Television central has developed good programs that are aimed at highlighting the retail industry. These programs are aimed to promote consumerism.

These initiatives were witnessed as early as 1998 when CCTV2 (CCTV’s economic channel) launched a pure retail program aimed at promoting consumerism. By the onset of 1999, the number of television channels in China surged considerably. At this time, it was estimated that more than 320 million television sets were in the hands of Chinese households (Weber 2000). However, at this time, CCTV was making a lot of profits from advertisements because it had already entrenched itself as China’s main television consumerism channel. Nonetheless, other regional television channels were giving the Chinese television giant a run for its money. However, because of the existing legislation, such competition could only be witnessed at the regional level because the competitors were not allowed to operate at the national level. The programs produced by such regional television channels were also aimed at targeting a local audience (Wei 2000; Xiao 2000; Xu 2000).

The Chinese television industry has since expanded to unimaginable levels. In 2006 it was reported that CCTV invested more than six million US dollars in support of the operations of CCTV6 which is a very popular national channel (Xu 2000). With such expansions in the offing, CCTV6 has promised its audience that it is going to develop many international blockbusters for the Chinese audience and broadcast them monthly (at least) (Weber 2000). This initiative is in line with efforts to elevate the Chinese viewership to international levels. Furthermore, this move is aimed at contributing to the development of the global culture in the Chinese local market. CCTV9 is also another subsidiary of the parent CCTV Company which mainly broadcasts in international language so that it can capture the international audience.

Recent reports show that the television subsidiary now hosts a blend of professional journalists from across the globe. The contribution of the television agency is also remarkable, considering it has played a pivotal role in introducing diversity and global understanding to the Chinese television market (Xu 2000). Regarding a recent remark made about Chinese business relations with Taiwan, one commentator said “it is helpful to the economy and feeling of communication between people across the straits, and it will promote mutual understanding” (Zhao 2000, p. 12). A recent production from CCTV aimed at capturing a young audience (children) has received a viewership base of about 300 million people (Weber 2000). Such a viewership base is only envied by most national television broadcasters. Such a figure also works to drive home the worthiness of producing such television shows in the first place. At this statistical level, it is only right to give credit to media people for being architects for building the bridge across the world through special charisma over economic interests that dominate modern-day television.

Arab Perspective

Predominantly, state media in the Arab world have been characterized by extreme government control. In this regard, new media has traditionally been very scarce in most Arab countries (especially in North Africa, Middle East and parts of Sub-Saharan Africa) (Kamalipour 1997). In such regions, governments have historically censored information and withheld vital public information for their own selfish interests. In turn, the public has often held their state media outlets with much contempt. Because of the scepticism held regarding state media information, other social and public places like mosques and public places have greatly rivalled information from state media houses (Howard and Idriss 2012).

Religion and community influences have also played a great role in defining the nature of state media in most Arab countries. However, this influence is slowly diminishing through the ease of regulation in press matters. Since such progress has been made, the volume of media houses offering information to the Muslim population has greatly multiplied. Consequently, the public has been offered a host of alternative and attractive media sources (different from what had been in the past). In the past, many mainstream media outlets only provided information from either the western perspective or the government’s perspective (Howard and Idriss 2012). Albeit the Arab media is slowly changing, sceptics still say that state media stations operating in this region are still incapable of promoting an international agenda (Howard and Idriss 2012).

European Perspective

In the European continent, a lot of debate has been growing regarding the production of local continent, viz-a-viz international content. Mainly, in Europe, international comparisons have been made to the American television market and more importantly, Hollywood (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). Interestingly, it is important to mention that there have been some growing concerns regarding the dominance of Hollywood over mainstream local productions. The perception here is that many local productions in Europe are increasingly copying Hollywood. While some of the barriers to attaining an international audience may be cultural, achieving this level of viewership is considered a strong ‘plus’ for local European productions (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006).

Part of the problem observed by most state media houses is the language barrier that some local European television programs experience when they want to achieve a global viewership. That said, some television producers have decided to produce their television shows in English. For example, some Danish television programs have been intentionally produced in English so that they can appeal to an international audience (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). This initiative is part of what this study aims to expose. In detail, the move to attain an international viewership is facilitated by the production of television shows in English and in this regard, the media is developing the bridge for cultural understanding. Albeit this move may be unpopular among some quarters, the production of television programs in more culturally understandable languages means that the weaker culture is paying tribute to the stronger culture, in pursuit of worldwide recognition.

Paradoxically, it is important to highlight that television has upheld its position as a host of national orientation even when the global culture continues to thrive. The argument here is that most state media stations in Europe support the production of television shows that can capture the domestic audience first. If an international viewership is attained, this is regarded as a ‘plus’. Television drama products shown in Europe today play host to the trend in intercultural understanding and exchanges because their producers are increasingly sensitive to global cultural trends. Therefore, the production, style, aesthetics and gender of such television shows are highly representative of the changes on an international level. This observation is part of the contribution that media people are building to facilitate cultural exchanges in today’s global society. As explained in earlier sections of this paper, European television productions use American television production as its common denominator because most European television shows are compared to American productions (even national channels) (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). Because of such comparisons, Michael Curtin (a media researcher) proposes that the concept of ‘nation’ should be replaced for the adoption of the concept of ‘media capitals’ such as Bombay, Cairo, Hong Kong and the likes (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). In Europe, there is no common reference to a media capital yet.

There have been many attempts to control media production in Europe so that they are more representative of the national context as opposed to the international context. Such attempts have been observed in the production of Danish television series because public service regulations often demand and encourage the production of television series that are more reflective of the national spirit. Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) acknowledge that such legislative provisions have been established because there is substantial fear that there is a lot of trans-cultural dominance in the Danish television market which threatens the very bedrock which the Danish national spirit thrives – media.

In Scandinavia, media people have created a dominant popular culture among most countries, thereby making it almost impossible to distinguish the difference between television programs made in one country from the other. However, Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) point out that in Scandinavia, most countries share beliefs and values and therefore have an almost equal standard of living which provides the framework for the acceptance of cross-cultural television programs.

To further expose the bridge that the media has created in intercultural understanding in Europe, it is notable to point out that Danes and Swedes have considerable differences in popular social and political beliefs, but Danes find it almost impossible to notice any difference between local television production and Swedish productions (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). This difference does not even arise in public debates.

The European media has gone to the extent of bridging elements of Australian popular culture into the European television system as was seen from the sitcom adaptation of Pas Pa Mor (“take care of mum”) which was adapted from a popular Australian sitcom – Mother and son (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). This sitcom was aired for ten years (1984-1994). The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) also interestingly adapted this sitcom between 1997 and 1998 by renaming it Keeping Mum. Danish television also received broadcasts of the television show with moderate ratings.

However, even though there have been attempts to introduce intercultural inferences in European television, Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) observe that the world is not often amused by the same things. In addition, Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) give an example that comedy/humour is often universal but people laugh at different things. The adaptation of the Australian television sitcom Mother and son was not well received by some sections of the British audience because the sitcom made fun of Alzheimer disease. Therefore, in as much as the sitcom was successful in Australia, it failed to capture the same level of positivity within the British market.

The overall assumption developed by observers in this regard is that comedy should be introduced to the international market with a lot of caution (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). This assumption is perceived to be part of the problem Danish television faces because it failed to factor intercultural differences and defined professional standards that could have guaranteed a positive reception among the local audience. Even though this observation portrays the extent that the media has gone to create a cultural bridge in the global society, critics of Danish television say that local media has gone out of its way to incorporate elements of British and American television at the expense of local domestic comedy traditions (Højbjerg and Søndergaard 2006). In detail, such critics point out that not enough attention is being given to domestic genre traditions such as folk comedy and satire.

Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) highlights that in commercial channels, the expectation would be that local television would consider domestic and international adaptations. In the 90s, it was extremely surprising to see that state media television stations were experimenting with global productions because the public policy at the time was to promote national and nationalistic sentiments. However, by the end of the millennium, a television revolution started where culture transfer traditions took centre-stage and domestic and international traditions merged through an intercultural bridge designed to introduce the global culture to domestic audiences.

Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) demonstrate that this dual strategy adopted by many European state media houses is not properly being implemented. Among the suggestions proposed by Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) regarding the incorporation of international culture into local television is fusing global culture (but maintaining the local format of production). For example, in Danish television, the adaptation of a police series named Skujulte Spo incorporated components of American models of television production but stayed true to the local format. The similarities in production can be seen from the selection of characters, identification of production themes, or even the production settings. Therefore, according to Højbjerg and Søndergaard (2006) domestic productions can be developed with an international appeal through the application of understood genres, myths or even the clusters of association. However, a word of caution is expressed regarding the application of domestic and universal models because there is no guarantee that such a strategy will be successful.

Jamaican Perspective

Jamaican state media has not been spared from the porosity of borders that globalization engenders. There is a lot of concern in Jamaica about the decline in national and cultural values because of the inflow or reproduction of international media content into the national mainstream media. There is however, no empirical evidence to show a cause-and-effect relationship between the decline in Jamaican national values and the consistent uptake of international and foreign content in state media television. However, Gordon (2008) points out that there is an imbalanced flow of communication and media content between Jamaica and the US or Britain. Statistically, the US is known to air commercial content based on its local productions. Due to the high number of American productions, the U.S has been reported to export at least 150,000 hours of programming to the rest of the world while it only imports 1% of its commercial television content (Gordon 2008). Interestingly, Jamaican media broadcasts about 76% of international content (most of which are imported from the U.S). Comparatively, the English speaking Caribbean population is treated to about 86% of foreign media content (a majority of which is also imported from the U.S) (Gordon 2008). A past study done by the Caribbean Institute of Mass communication depicted a situation where the country was mainly flooded by international television production, thereby tilting its national values, beliefs and attitudes towards the North American way of life.

Gordon (2008) points out that the cultural reciprocation in today’s global society is non-existent. In this regard, he demonstrates that the proliferation of international content into Jamaica’s mainstream media cannot be contextualized in the understanding of cultural hybridism. Concisely, in this light, Gordon (2008) doubts the equality that intercultural exchange is being contextualized in today’s global society. Interestingly, these observations are not factored into criticisms against globalization and its antecedents, particularly because only selective countries are reaping the benefits of cultural exchange.

In light of this observation, Gordon (2008) reports that this imbalance is particularly striking when one considers the fact that the world trade in cultural commodities has almost tripled between 1980 and 1991 from about $61 billion to $200 billion (Gordon 2008). Currently, this figure has almost doubled. What this statement signifies is that, while intercultural exchanges are being fostered through the media, just a few countries are benefitting from this exchange. Similarly, while global trade in intercultural exchanges is generating a lot of profits from revenues, national cultures and values are declining fast.

Hollywood alone is estimated to contribute more than 70% of all media content in Europe alone (Gordon 2008). Asian giants like Japan are also not alien to this trend because about half of their media content is also Hollywood-dominated or Hollywood-inspired. The contribution of Hollywood media content is estimated to be at much higher levels in Latin America (83%) (Gordon 2008). It is therefore unsurprising that domestic media productions in Mexico have declined considerably in the past few years.

The level of criticism for intercultural exchanges through state media is however minimal for countries like China and India because these countries have been able to establish a strong cultural presence in their media productions. Therefore, compared to the rest of the developing world, China and India do not have a lot of international cultural influences in their media productions. Through this observation, Gordon (2008) highlights the failure of global culture critics to show the relative success of conservative democracies such as India and China in today’s society which is dominated by consumerism sentiments (especially considering China and India have high populations). Comparatively, countries such as Jamaica have relative smaller populations (about 4 million) and therefore, they do not hold much significance in the intercultural bargaining table.

In countries where populations are relatively small, it is also not unsurprising to see that cultural exchanges are mainly one-sided. However, according to Gordon (2008) “For some developing countries, the lack of a strong base for film and television production, the absence of a large economy of scale and the lack of program innovations can be factors contributing to the influx of foreign media productions” (p. 68). Having large economies of scale is an important factor in the production of media content because it means having a large market for the consumption of goods and services. A large economy of scale also means that local media content can be produced at relatively cheaper costs as opposed to a situation where there would be no economies of scale at all. Therefore, developing countries (or even developed countries) that do not enjoy economies of scale find themselves at a competitive disadvantage in the communications industry because they have to produce quality programs at relatively high costs as compared to other media producers who enjoy economies of scale. Conversely, to support the local media content of such economies, foreign media productions have to be imported. Gordon (2008) cautions that with this trend, local media productions are going to be adversely affected in the future.

Theoretical Background

The field of communications and media is very broad. Being a relatively new and evolving field of study, media studies have tried to entrench and consolidate their findings as a new field of study. Through this analysis, media studies have been theoretically founded and consequently, theoretical developments and debates have been developed intentionally (to mean that media development theories have been designed to address something out of the theoretical confines). Part of the development process for this theoretical understanding has been influences by international theoretical conditions. To explain the role of the media as modern architects who facilitate cultural exchange, several theories can be used to explain this phenomenon. Among such theories are:

Social Exchange theory

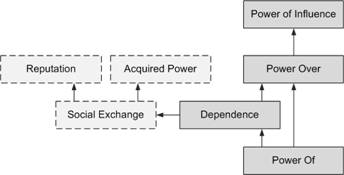

The social exchange theory has often been compared with the rational choice theory and structuralism because of their similarities (Thomas 2011). The social exchange theory infuses social psychological and sociological perspectives that explain the social construct we see today as a product of societal exchanges (Baker 2001, p. 78). Partly, through the social exchange theory, we are able to derive power and reputation. The following diagram shows this relationship

The ideologies of the social exchange theory have been borrowed from different disciplines, including economics, psychology and sociology because some of the main concepts of the theory are costs, rewards, worth (rewards – costs), satisfaction, dependence and outcomes.

The social exchange theory bases its philosophies from a few assumptions about human relationships. The main assumptions of this theory is that humans always seek rewards and avoid punishment, humans are rational beings and the standards which people use to measure rewards and costs often vary periodically (Thomas 2011). However, a few criticisms have been levelled against these assumptions. For example, the game theory has been advanced to dispute the assumption that people will often cooperate when they have something to gain because the theory posits that people may still act selfishly even if there is something to be gained from mutual cooperation (Baker 2001).

Other theorists such as Katherine Miller have expressed their reservations about the social exchange theory by stating that the theory stresses a lot of importance on the economic theory, thereby reducing human relationships to nothing but rational exchanges (Chibucos and Leite 2005). Secondly, Miller objects to this theory by stating that the theory was developed at a time when the freedom movement was dominant and therefore openness in human relationships was desirable. However, she says that there are times when openness is not desirable. The social exchange theory also suggests that the ultimate goal of human relationships is intimacy but Miller objects to this assumption by stating that this may not always hold true (Chibucos and Leite 2005). Finally, Miller criticizes the social exchange theory based on the fact that it describes human relationships in a linear structure while this may not be the case because people may go back on intimacy or may skip some steps in the linear relationship trajectory (Chibucos and Leite 2005).

To some, the application of the social exchange theory to this study may not be that open. However, this theory demonstrates the nature of human relationships which is equally defined by intercultural exchanges. In any case, for cultural exchanges to work they must be based on the successes of human relationships and therefore through the explanations that the social exchange theory gives in understanding human relationships, we can equally understand the nature of intercultural exchanges. Indeed, Pan (2012) explains that

“Social behaviour is an exchange of goods, material goods but also non-material ones, such as the symbols of approval or prestige. Persons that give much to others try to get much from them, and persons that get much from others are under pressure to give much to them. This process of influence tends to work out at equilibrium to a balance in the exchanges. For a person in an exchange, what he gives may be a cost to him, just as what he gets may be a reward, and his behaviour changes less as the difference of the two, profit, tends to a maximum” (p. 3).

Through the above assertion, it is simpler to understand how intercultural exchanges occur through the media and how existing communication tools have been used to facilitate this exchange. On a social front, we can say that the social exchange theory facilitates our understanding of why we terminate or foster mutual understanding between different groups. An article by Harumi Befu (a social researcher) also exposes the importance of the social exchange theory in understanding cultural and social norms such as marriage and gift-giving but a large application of this theory has been used in anthropology (Baker 2001).

Communications Accommodation Theory

Howard Giles developed the theory of communications association to explain why people often change their communication approaches to suit others (Dainton and Zelley 2010). This understanding also explains why people often change their vocal, speech and linguistic patterns to suit other people. The communications accommodations theory also strives to explain why people try to minimize the cultural divide among them, through verbal and non-verbal communication. Mainly, the communications accommodations theory is focused on explaining language, context and identity as the main concepts defining intercultural communications.

These concepts are mainly applied in the intergroup and intercultural contexts to explain accommodation and how power within the state and international context affect communication behaviours. The communications accommodation theory focuses on two main accommodation processes – convergence and divergence (Dainton and Zelley 2010). On one hand, the concept of convergence often denotes the adaptation of communication behaviours within two cultural groups to reduce social differences while on the other hand, the concept of divergence refers to the accentuation of speech and non-verbal differences to better facilitate communication. Dainton and Zelley (2010) points out that the problem with convergence is that sometimes people pass the boundaries and tend to over-accommodate the cultural dynamics of another group. Victims of such occurrences can also exaggerate the dynamics of another group.

The communications association theory also suggests that people often bring their experiences and backgrounds to their communication and speech styles and therefore, through this understanding, the theory proposes that speech and behavioural similarities often exist in media productions. Notably, the communications association theory proposes that accommodation is mainly informed by the perception and interpretation of messages within specific broadcasts (Dainton and Zelley 2010). Perhaps, the main distinguishing feature about the communications accommodation theory is its departure from the premise that language behaviours determine a group’s social class. Regarding this assertion, Turner and West (2010) add that “It is for this reason, that in their desire to identify with the group that has a higher social standing, individuals engaged in conversation with someone from a higher status group will usually accommodate to their interlocutor” (p. 57). Since the communication association theory is widely used to explain interpersonal and intergroup communication behaviours, it is therefore no surprise that it has also been used to explain inter-cultural exchanges (hence the relevance to this study).

For example, like the media, tourism is a well-known platform where intercultural exchanges occur. Turner and West (2010) observe that, mainly, tourism occurs between developed and developing nations where different cultural dynamics are merged. Citizens from developed nations spend millions of dollars visiting some of the best tourist destinations in the world and often, such destinations are in the third world. Millions of visitors from developed countries therefore traverse the globe each year in vacations, holidays, adventures and such like activities. However, interestingly, not many of these tourists are interested in learning the culture, language, economy and way of life of some of the inhabitants of these tourist destinations. Nonetheless, many third world citizens parade themselves to learn the culture, beliefs and way of life of these tourists. Here, there is an imbalance in cultural exchange between these two cultural groups but few take notice.

Turner and West (2010) explain this phenomenon through economic rhetoric by explaining that in the tourism circle, the inhabitants of these destination countries rely on the tourists for their economic well-being and therefore, they got out of their way to learn their culture. However, the opposite is not true. Citizens from developed nations do not depend on the inhabitants of such tourist destinations for their livelihoods or well-being. Therefore, they are not motivated to learn their culture, language and way of life. This example also coagulates with earlier assertions in this paper regarding imbalanced cultural exchanges within the media. Examples are given of Jamaica and the Caribbean where there are many imports of media content from America while America only imports about 1% of its media content from developed nations. The similarity with the tourism example is seen with the similarities of America as the culturally superior media provider while Jamaica and the Caribbean are culturally inferior. The communications accommodation theory defines this relationship by explaining the redesign of media structure to accommodate the culturally superior group in order to facilitate communication (Turner and West 2010).

Criticism against Media as Modern Architects

Like any debate, there are two conflicting sides. This paper supports the argument that the media has acted as an architect to the intercultural bridge which is evident in our present-day society. However, there are counter arguments to this understanding. These counter arguments are represented by critics of the role of the media in created intercultural understanding in present-day society. Part of the problem suggested to be created by state media and global media architects is the creation of extremist sentiments which continue to divide our society every day. Some of these divisions are discussed below.

Islamist Extremism

Today’s society is characterized by several extremist sentiments among people who share different philosophical ideals. Contrary to the argument pursued by many proponents of the media as a dominant architect to intercultural understanding, critics of the media suggest that the media is partly to blame for the role of sharply dividing the global society (Howard and Idriss 2012). Part of this argument has been supported by the deeply-rooted religious rhetoric in the Muslim world which advocates for an anti-western agenda. The role of the media in fuelling such arguments is undisputed but it is important to highlight that, just like the society, the media does not speak in one voice. Because of this reason, state media architects have designed their communication broadcasts to serve varied interests. In the past, these interests were mainly defined by government wishes but in today’s globalized society, commercial and sectarian interests are increasingly becoming dominant in media operations (Eadie 2009). For this reason, certain media architects have defended different interests while bashing others. For example, regarding the religious extremism around the Islamic peninsular, Arab media houses and western media stations have been cited to fuel the religious tensions between these two groups.

Notably, Arab media stations such as Al Jazeera have painted Muslims as victims of western agendas (thereby calling for a redemption of the status quo) (Gudykunst and Mody 2002). The situation is not any different for western media stations because they have been accused of advancing a western agenda. In detail, such agendas are criticized to be supportive of domination or unfair justice from western powers. This division is very apparent in today’s media debates and depending on whom you ask; every media empire is right in its own accord.

It is from this division that researchers, such as, Howard and Idriss (2012) paint a grim picture of societal misunderstandings in today’s global society. Their sentiments further deepen with the entrenchment of media activities in today’s society and the subsequent spread of information that is characteristic of the Muslim information and communication industry. Some of the concerns expressed by Howard and Idriss (2012) highlight the relaxation of press laws, the penetration of the internet into the Muslim society and the development of popular regional satellite televisions as some of the main dangers of a deeply entrenched sectarian media. In Howard and Idriss’s view, the entrenchment and liberalization of Islamic media signifies the entrenchment of sectarian ideals which do not add value to the global community (Howard and Idriss 2012).

The victimization of Muslim populations has especially been highlighted by such media because the Muslim population is now more aware of the events that happen in Iraq, Palestine, Afghanistan and other far-flung places of the Islamic peninsular that have had a direct interaction with western forces. The broadcast of these events appeal to other Islamic people and because they sympathize with their Muslim brothers, they are likely to develop negative attitudes about the people they believe to be inflicting harm to others. This is the basis for most global conflicts today. These media centres therefore tend to create anger among its viewers (and in this context towards western powers who are perceived to support western philosophies over countries that are either perceived to be too weak to contradict them or unsupportive of western ideas) (Howard and Idriss 2012).

A recent report, done by Nicole Argo (a journalist), presents an interview of a Muslim suicide bomber who was angered by media reports showing the victimization of Muslim populations by western nations. Sentiments from an excerpt of his interview stated that

“The difference between the first intifada (no suicide bombers) and the second is television. Before, I knew when we were attacked here, or in a nearby camp, but the reality of the attacks everywhere else was not so clear. Now, I cannot get away from Israel! The TV brings them into my living room, and you cannot turn the TV off. How could you live with yourself? At the same time, you cannot ignore the problem. What are you doing to protect your people? We live with an internal struggle. Whether you choose to fight or not, every day is this internal struggle” (Howard and Idriss 2012, p. 4)

From the above narration, the role of the media as an architect for inter-cultural understanding is greatly doubted. Through the role of the media in perpetrating negative messages, we assume that instead of the media bridging social divisions, it creates negative sentiments within the general populace, thereby creating further intercultural and inter-social misunderstandings. This view will be considered to be part of the overall understanding of the research problem but subsequent literatures will subject it to more scrutiny.

The Internet and the Digital Revolution

Like any other industry, telecommunications and media has evolved tremendously. Gone are the days when media used to be closely guarded by state media stations and different pieces of information doctored to suit the interest of only a few individuals. Over the years, the telecommunications industry has been heavily liberalized and with this new paradigm, new technology has crept into the media industry. Perhaps, there is no better way to represent this technological revolution than through the onset of the digital revolution which has been greatly fanned by internet penetration. The study of the internet and digital revolution is important to this paper because of the focus of the media as modern architects who facilitate cultural exchanges. From the earlier assertions of this paper, the scope of the media has been limited to global and state media but because of the digital revolution and the spread of the internet, the scope of state media and global media architects has spread to the digital world. Now, many media stations do not want to be left out from the digital revolution and many media practitioners are adopting existing digital platforms like social media to complement their ‘normal’ broadcasts.

Currently, most state media stations have a website and at least a Facebook page or a Twitter account (Hall and Grindstaff 2010). These media platforms have emerged as alternative communication channels that have often rivalled traditional media (largely, because of the shortcomings of mainstream media – like government manipulation). The power of digital media cannot be ignored because its impact has been proved to be more intense than even traditional media (Howard and Idriss 2012). For example, the ability of social media to mobilize people around specific issues has been epic. Indeed, social media sites such as Youtube, Facebook and Twitter create a culture salon (cultural melt point station) after they subject different pieces of information through cultural tests and culture mobs. Often, this occurs through random exposures (Hall and Grindstaff 2010, p. 605). The power of social media in promoting cultural exchange is hereby undisputed. For example, the ongoing Middle East revolution is largely attributed to the power of social media. Revolts in Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Libya and other countries which have experienced the brunt of the uprising have largely been structured around social media revolutions. In the spirit of getting a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem and understanding the complete dynamics of the role of the media as architects of cultural exchanges, it is vital to explore the role of the internet and the digital revolution.

The advent of the internet and digital media has changed the way media is produced and disseminated. Interestingly, there is a big generational divide in the manner different people view digital media and its importance in today’s world because Howard and Idriss (2012) posit that generations which were born before the 80s find it more difficult to comprehend the power and importance of new media in today’s world. However, to elaborate the importance of the internet and digital media, Howard and Idriss (2012) compare the power of the internet and digital media to Martin Luther King’s assertion that “there is a new medium that has been invented called the Television and through it we are going to show the brutality of what we have been facing all of our lives” (Howard and Idriss 2012, p. 21). Therefore, through Martin Luther King’s assertion, Howard and Idriss (2012) draw a conclusion that the advent of the television as part of mainstream media could be compared to the advent of digital media in today’s society.

The power of digital media should especially not be underestimated when promoting cultural exchanges among the youth (Dirckinck-Holmfeld and Hodgson 2011). According to a recent survey done by the Kaiser Foundation, it was reported that youth aged between 15 years to 18 years spent most of their time watching television, surfing the net or playing online games (Howard and Idriss 2012, p. 21). This statement only goes to show the potential impact of digital technology on the youth. Social networking is another platform which has almost quadrupled since the year 2000. Currently, social networking sites like Facebook, Myspace and Twitter boast of millions of users who frequent the site daily. Facebook for example is known to host among the world’s highest number of internet traffic in any given day (Howard and Idriss 2012).

Coming closer to the link between digital media and traditional media, global media stations such as CNN have reported that their web traffic has tripled over the years and currently, the global news agency boasts of more than 60 million users (Howard and Idriss 2012). According to a global new agency reported in Howard and Idriss (2012), CNN’s website was ranked to be the sixth most visited website in the world. The importance of this media platform in the understanding of this paper stems from the fact that through the global media websites, millions of people around the world are able to share videos, photos, information and other pieces of information, thereby facilitating intercultural exchange. The range of media content that is communicated across such media platforms may vary from home-made videos to amateur videos. These media contents generate a lot of interests and comments from people all over the world, thereby rivalling the kind of interest or awareness that traditional media generates. Based on the amount of attention such content generate online, traditional media has been forced to broadcast such contents on their conventional media outlets as well.

Notwithstanding the potential of digital media to create divisions within the society, the internet and the digital revolution provide among the most fertile grounds for cultural exchanges. Similarly, traditional media, which have freed itself from intense government control and cultural limitations provide good opportunities for facilitating an inter-cultural agenda that digital media seem to generate. In my opinion, these are avenues that can be used to promote accountability within the increasingly deregulated media industry because traditional media can include their professionalism in interacting with audiences on digital media platforms. More importantly, traditional media should use such platforms to encourage the exchange of alternative views which cannot be accommodated within mainstream media broadcasts to encourage alternative perspectives on state and international issues. Some constructivist perspectives which are not accommodated within mainstream media broadcasts may also find their voice here. According to Howard and Idriss (2012), this is the only way that traditional media can have a large-scale impact on national and international audiences.

Albeit the importance of digital media and the internet revolution to promote intercultural exchanges, Howard and Idriss (2012) point out that traditional media practitioners should learn from the new revolution and reduce their intercultural ignorance through face-to-face interactions and familiarizations. This attitude can also be better promoted through exchanges and skills sharing. Howard and Idriss (2012) suggest that, to improve the impact that traditional journalists have on different populations, it is very important to invest in internet access and penetration so that populations which do not have traditional media broadcasts (or those that have lost interest in the same) are reached through such platforms. Mostly, such investments can be better undertaken by governments, but it is equally important to acknowledge the input that international organizations have had on the same (such as the UNESCO’s support of the Rabat Conference on Fostering Dialogues among Cultures and Civilizations which was held in 2005) (Howard and Idriss 2012). This conference was aimed at promoting intercultural understanding and skills transfer among journalists. From hindsight, it is inevitable to point out that the advent of digital media has not only supported cultural exchanges among audiences but also among media architects (journalists) too. The commitment of governments and other state agencies to promote this cultural exchange has been unimpressive but Howard and Idriss (2012) point out that the trend is continuously being supported by non-governmental agencies.

Role of Governments in Cultural Exchanges

Since state media is perceived to account for the high number of intercultural exchanges in the world, it is important to highlight the role of governments in supporting the activities of such media corporations.

United States

In America, the production of cultural products started as part of a cold war campaign to support democracy by showing artistic products that can be produced from a democratic society (Howard and Idriss 2012). The US information Agency is a notable government organization that has contributed to the imbalanced cultural exchange we witness between the US and other nations because it has promoted artists around the globe to market the American culture. Over the years, the contribution of the US information agency in cultural exchanges has declined and its role supplemented by private entities (Howard and Idriss 2012). The functions of the US information agency have been consequently integrated into the country’s department of State (in 1999). Albeit private funding in the US is significantly higher when compared to other countries, the system still remain hugely under-funded, particularly in respect to cultural exchanges with non-conventional markets like the Arab world (particularly, the Middle east). Europe currently enjoys a bulk of the funding for intercultural exchanges because Howard and Idriss (2012) slate the European bulk of cultural products to receive 30% of all media funding. Relating to this assertion, Howard and Idriss (2012) explain that “In the US, funding for production and presentation of work has dominated international arts grant-making, while support for extended artists’ residencies, contextualization of work, and touring has been limited” (p. 6).

The above assertion is known to be true for domestic artists and international artists as well. However, it is interesting to point out that the works of foreign artists tend to dominate only a few venues, after which, it fails to spread to other parts of the country. This observation reinforces the view that there is a lot of cultural imbalance between the US and other countries.

Europe

Intercultural exchanges in Europe are not easy to demonstrate because of the differences in policies and provisions within each country of the European Union. Different countries within the E.U therefore have different views regarding intercultural exchanges (notably in their state media) (Pauwels and Kalimo 2010). These views are mainly informed by the proportion of immigrant communities, viz-a-viz the general population. For example, the U.K has a high proportion of immigrant communities and therefore, it has a more relaxed intercultural exchange policy when compared to other European countries. However, some European governments invest a lot of money in intercultural exchanges through information networks and other cultural markets in the media to even surpass some of the world’s giant producers of cultural products such as the U.S (Pauwels and Kalimo 2010).

Notable countries that give U.S a run for their money include U.K, Germany, Netherlands, and France (Howard and Idriss 2012). Some of these countries do not necessarily invest in media as their main avenue for promoting cultural exchange because they also use quasi-diplomatic options to achieve the same results such as the establishment of the Goethe Institute in Germany that promotes the German language internationally. The Alliance Francais is France’s quasi-diplomatic channel for cultural promotion while the U.K uses the British Council to achieve the same results (Pauwels and Kalimo 2010). The activities of these institutions can be equated to the role of the U.S information agency, although their mandate does not include introducing foreign cultures in their domestic markets (although this occurs occasionally).

However, there have been some initiatives within the wider European continent to promote intercultural exchanges within the European peninsular. For example, Howard and Idriss (2012) explains that

“At the regional level, while resolutions have been passed in the European Union for European cultural initiatives since the 1970s, only in 1991 did the EU officially begin to deal with culture under the Maastricht treaty; however, this focused on intra-European exchanges and preservation of cultural heritage” (p. 8).

The Euro-Mediterranean Council partnership which was launched in 1995 is one such initiative because it opened new avenues for intercultural exchanges between the E.U and the South Mediterranean countries through different social, economic and political initiatives. A similar initiative is the Barcelona Declaration (Socio-cultural and human chapter) which promotes cultural exchange through human partnerships in civil societies. The Euro-Med Anna Lindh Foundation in Egypt is also another initiative adopted by some European countries to foster intercultural understanding between Egypt and Europe (Howard and Idriss 2012).

However, the obstacles to cultural integration in Europe are largely similar to the US because both regions only promote intercultural exchanges at bi-lateral levels as opposed to regional levels (because of the diversity in perceptions and attitudes within European and American states). There is no centralized body which is mandated to facilitate cultural exchanges within the U.S but it is only until recently that Europe is making such efforts, but with different levels of commitment among different countries (Pauwels and Kalimo 2010). This move was made because there have been several opportunities for cultural exchanges that could be seized to benefit every country that is involved. Such initiatives included a past dedication of 2008 as the year of intercultural dialogue within Europe (Pauwels and Kalimo 2010).

Middle East

It is difficult to generalize efforts of intercultural exchange in Middle East like Europe. This difficulty is experienced because there is a very wide cultural and geographic breadth within the Middle East. However, it is important to highlight the fact that the infrastructure for cultural exchange within the Middle-east is very weak or non-existent (Howard and Idriss 2012). The unwillingness of state media companies to promote cultural exchange is an example of the inherently weak cultural exchange infrastructure. Alongside the unwillingness of state media to promote cultural exchange is the unflattering intention of private philanthropists to facilitate intercultural exchange. Very few private entities are even allowed to promote cultural cohesion without much government scrutiny (Sakr 2004). Since there are many structural weakness of promoting cultural cohesion, it has been very difficult for foreigners to promote foreign cultures within the Middle East. Very few partnerships have been witnessed between western partners and Middle Eastern cultural institutions and media. For example, some notable western organizations promoting cultural exchange include the Ford Foundation and the Christensen work but these organizations have to partner with private entities in the Middle East who have adequate knowledge about the local demographics (Sakr 2004). Their partnerships have mainly been confined within arts and culture.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight the unwillingness of the government to change status quo by holding on to conservative ideals in local media, thereby frustrating efforts to include foreign content in domestic media (Sakr 2007). The presence of a large and conservative Muslim population is also very discouraging to the efforts to liberalize Middle-Eastern media. Extremist sentiments within the Muslim population particularly hold strong opinions about the influence of the west in their media because they perceive western influence as a threat to their Islamic values. For example, Howard and Idriss (2012) points out that a large section of the Muslim population believe that artistic productions are products of individualism and by extension, they equate individualism to political or even religious rebellion. The overall outcome of the Middle-Eastern media is a constrained and conformist media which is muzzled by religious and governmental policies (or way of life). Artists for example, have contended with constricting their artistic voices, failure to which they will receive the wrath of the government or the society. Comprehensively, the Middle Eastern media has not played a huge role in facilitating cultural exchanges because of religious and political reasons (Sakr 2004).

Methodology

This research methodology is aimed at providing a comprehensive understanding of the research problem but more importantly, it articulates the right strategies that will be used to answer the research questions. In addition, this chapter aims to provide a broad view of the research topic so that different aspects of the research problem are better explained to have a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem. In detail, this research methodology will encompass different views from varied sources to have a holistic understanding of the research problem. Through the methodology, this chapter aims to answer: what media platforms are effective for cultural exchange, what roles have governments played in enabling cultural exchange through media, what impact has the digital revolution had on state media and its effectiveness in facilitating cultural exchange and whether the media plays a balanced role in cultural exchange. These research goals will facilitate the holistic comprehension of the research problem because they enlist the understanding of the research problem from different perspectives.

Research Design