Abstract

This research study examines the economic efficiency and operating of different microfinance institutions (MFIs) and that are based in China. In carrying out a comparative analysis of economic and operating efficiencies, the researcher used the Input Distance function in evaluating allocative and technical efficiencies as part of the input factors and Data Envelopment Analysis to comprehend the technical efficiencies into scale function. The study also carried out a comparative review of sectoral microfinance institutions about the best practice microfinance institutions to identify factors affecting efficiencies. The findings suggested that there exists no difference between microfinance institutions and commercial banks in China in terms of their technical efficiencies. Moreover, the comparative analysis between the agriculture-based MFIs and other microfinance institutions indicated that the former have relatively higher scale, pure technical, and technical efficiencies levels than the latter. The findings further indicated that the efficiency variations in Chinese microfinance institutions are swayed by factors defining institutional operational frameworks. Generally, the Chinese microfinance institutions need to improve on their economic and operative efficiencies to have a suitable and sustainable impact on the capital needs of middle and low-income households.

Statement of Originality

“I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by myself and has not been presented or accepted in any previous application for a degree. The work, of which this is a record, has been carried out by myself unless otherwise stated and where the work is mine, it reflects personal views and values. All quotations have been distinguished by quotation marks and all sources of information have been acknowledged using references including those of the Internet. I agree that the University has the right to submit my work to the plagiarism detection sources for originality checks.”

Statement of Secondary Use

“This report may be made available for photocopying and inter-library loan. However, secondary usage is limited to academic research.”

Introduction

Across the globe, low-income households are often excluded from the borrowing clientele base for most formal financial institutions. The level of exclusion ranges from partial in developed nations to full isolation in developing countries. Dissociated from borrowing capital from formal financial institutions, this group has come up with alternative informal financial arrangements aimed at meeting their financial needs (Waters 2013). These plans are managed within a community of low-income people in the form of groupings that pull together financial resources for members. Before the establishment of formal microfinance institutions in developing nations, low-income households heavily depended on unreliable private and informal lenders with exorbitant interest rates (Gupta 2014). Instead of improving the financial position of these low-income households, these expensive lenders made the situation worse since the arrangement does not benefit the borrower (Jamali, Lund-Thomsen & Jeppesen 2017). Microfinance institutions in China are relatively immature since they have been around for less than two decades. However, in the last ten years, there have been improvements in the capacity and coverage of these institutions among middle and low-income households.

Research Background

Often referred to as the solution to low-income households’ capital or financial needs, microfinance is a complex plant intended to provide affordable financial services to persons in the population categorized as poor (Jeffrey 2013). The microfinance institution is a movement that has comprehensive, broad, and encompassing financial programs that go beyond the provision of microcredit to low-income households. Factually, the organization of the microfinance movement encompasses targeting middle and low-income households that are isolated from access to formal financial services due to their non-creditworthy status (Guo & Guo 2016).

The development of microfinance institutions in China is relatively a new phenomenon, that is, it was inaugurated by the government less than 20 years ago. Specifically, the process began in the early 1990s following successes of similar arrangements in neighboring countries in South Asia (Gras & Nason 2013). The setbacks in the development of microfinance institutions in China are unique due to excessive government involvement and expansive regulatory framework, especially in rural areas.

At present, the Chinese microfinance institutions are organized within a three-tier finance system comprising of the Agricultural Bank of China, Rural Credit Cooperatives, and Agricultural Development Bank of China (Ghosh 2013). These lenders are active in supporting farmers through affordable credit facilities. Specifically, the Agricultural Development of China and the Agricultural Bank of China both support the highest number of small scale agricultural enterprises across China. Moreover, Rural Credit Cooperatives concentrate on the provision of affordable financial credit services to households within rural areas of China (Gervasi 2016).

This research study is created to comprehend the challenges of inefficiencies of microfinance institutions in operating China under the lending regime. Specifically, the proposed study will approach these challenges from the perspective of operating efficiency. The listed literature sources suggest that China’s microfinance institutions are grappling with inefficiency challenges and there is a need for focused development and improved operational framework. Therefore, this report will attempt to propose solutions that would make microfinance institutions more efficient and suitable.

Research Problem Statement

In the last three decades, the formal financial system in China has experienced a paradigm shift to improve resource allocation and operational efficiencies. Under the previous planned-economy model practiced by China in the late 1970s, financial sector efficiency was not a major concern (Gasmelseid 2015). Interests in sectoral efficiency merged during and after the financial reforms. For instance, the structural changes as a result of the reforms affected the financial system, especially the banking industry, in terms of performance (Founanou & Ratsimalahelo 2016). Therefore, it is important to carry out a study on operational and performance efficiencies within the financial systems in China to establish policies, expand the performance of managerial strategies based on best practices and examine how efficiency can be quantified. Unlike microfinance institutions, commercial banks are focused on the integration of strategies for optimizing profits while minimizing losses or operational costs (Forcella & Hudon 2014).

Therefore, financial institutions have adjusted their operational strategies in line with the regulatory and economic environment. Although there are studies that have been carried out to add to existing empirical knowledge on the performance and efficiency of financial institutions in China, most of these researches were focused on the commercial or formal banking sector. Therefore, there is a need to carry out this proposed study to fill this literature gap by establishing the performance and operational efficiencies of the microfinance institutions. Performance efficiency is an instrumental element in the traditional formal agricultural lending institutions in China that target low and middle-income households (Estapé-Dubreuil 2015).

Unlike commercial banks, these institutions are concerned about their liquidity since their targeted markets consist of relatively poor borrowers with the unpredictable capacity to repay (Ensari 2016). In China, the Agricultural Development Bank of China and the Rural Credit Cooperatives have not been able to diversify their clientele base to incorporate other borrowers from non-agricultural sectors such as light and service industries (Dimitrieska 2016).

The inability to expand the clientele base could be associated with limited funds and complex government regulations. Due to the focused and specialized lending operational framework, these institutions are currently exposed to uncertainties and other operational risks (Dhliwayo 2014). In line with this argument, it is to state that result of efficiency review within the commercial bank’s framework might not present the actual picture of the occurrences within the traditional small-scale agricultural lenders. This is because is it not possible to draw parallel conclusions due to variances in lending operational styles (Dhitima 2013). For instance, traditional small scale agricultural lenders in China do not make decisions using economic or financial market rationale as the commercial banks (Waters 2013). This means that the drive for traditional lenders is policy-driven as opposed to maximization of profits and minimization of losses as is the case with commercial banks (De Melo & Guerra Leone 2015).

These policy-driven lending mechanisms are not perfectly aligned to any conventional principles of risk and returns. Moreover, the traditional agricultural lenders’ ability to optimize profits is heavily influenced by the productivity of the agricultural activities of the borrowers (Daidj 2016). This means that the traditional agricultural lenders in China are exposed to great risk of loan default due to bad harvest or reduced market prices for agricultural produce. These risks make the traditional agriculture-based lenders have inconsistent operational strategies and objectives when compared to stable and predictable approach by commercial banks (Cozarenco, Hudon & Szafarz 2016). Given the discussed challenges in operational objectives and strategies of microfinance institutions in China, it is important to compare and analyze efficiencies of different microfinance institutions at the sectoral level to reveal their operational strategies that might improve the short and long-term efficiency conditions.

Research Objectives and Questions

The primary objective of this research study is to carry out a comparative review of the economic and operational efficiencies of microfinance institutions in China. The study will fulfill this objective by examining the efficiency performance of selected microfinance institutions in comparison to commercial banks between 2013 and 2017. Therefore, the specified objectives are;

- To perform a comprehensive comparative allocative and technical efficiency analysis of three microfinance institutions in China to establish the relative efficiency.

- To compare and decompose the existing technical efficiencies of microfinance institutions in China to establish specific inefficiency sources in operations across different sectors.

- To evaluate the Chinese microfinance institutions’ efficiencies by examining the effects of structural variations across different sectors

Based on the above objectives, the following research questions were generated to address the primary aim of a comparative review of the economic and operational efficiency of microfinance institutions in China.

- What are the allocative and technical efficiencies of three microfinance institution sectors in China in comparison to one another?

- What are the existing inefficiencies of microfinance institutions and their sources in China?

- What are the effects of structural variations across different sectors of microfinance institutions from an efficiency perspective?

Research Significance and Rationale

The proposed study will attempt to fill the identified literature gap in the economic and operational efficiency of microfinance institutions in China. This means that the findings of the research will present vital insights into primary sources of economic and operational efficiencies and inefficiencies of Chinese microfinance institutions. Specifically, the proposed comparative review of sector-based microfinance institutions in China will expound the impacts of government interventions and direct involvement on the efficiency in costing the microfinance loans. The researcher will also review the impacts of agricultural and micro-lending components of microfinance institutions’ efficiency in managing the lending operations.

Through the integration of commercial banks as the primary efficiency comparative matrix, the proposed study will examine the aspect of concentration of agricultural and microloans within the lending portfolios of microfinance institutions when implementing strategies for enhancing efficiencies. Since scarcity of funds is the primary expansionary challenge facing microfinance institutions in China, the proposed study will highlight key insights on how to sustain the viability and ultimate survival of the microfinance institutions that provide capital to low and middle-income households.

Research Conceptual Framework

Analysis of efficiency instruments can be done using approaches such as the semi-nonparametric approach, parametric approach, and a non-parametric approach. Factually, the parametric approach functions on the assumption that specific institutional function form is strict as opposed to a flexible regime as proposed in the semi-nonparametric approach (Couchoro 2016). This means that using either parametric or semi-nonparametric approaches would mean that the functional restrictions will be maintained at a minimal level to ensure nonbiased estimations (Cooper 2015). The requirement of assuming functional form makes the semi-nonparametric and parametric approaches relatively inflexible.

This means that the proposed study will adopt the nonparametric approach since it can function without a specific explicit functional form. Despite this strength, this framework has several drawbacks such as an excessive focus on technological optimization at the expense of economic optimization and assumption of the deterministic route as opposed to the stochastic approach (Cincotta 2015).

However, a simple simulation would minimize the impacts of these setbacks on the final results. The nonparametric method will be used by the researcher to measure the efficiency of matrices during the study. The researcher will also integrate the Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) to identify the allocative and technical inefficiencies (Chinomona 2013). Also, the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) will be used in the study to decompose any technical inefficiency identified into the scale and pure technical inefficiencies.

The identification of allocative inefficiency and technical inefficiency will involve decomposing operational. This action aims to use stochastic Translog input functions in evaluating the operational efficiency while estimating the allocative and technical inefficiencies for three groupings of microfinance institutions in China (Bumacov, Ashta & Singh 2014). The distance function is a key instrument in estimating the input production technologies and multiple-output characteristics when the price information is scanty or blank. Moreover, the distance function would be ideal when the profit maximization and cost minimization assumptions are not appropriate (Brière & Szafarz 2015).

Within the banking or formal financial sector, it is a common occurrence that maximum profits or minimum costs are not set as primary objectives, especially for the microfinance institutions and other policy-based banks. Moreover, the formal financial sector does not have full control of outputs as opposed to inputs (Braun, Clarke & Terry 2014). Based on this argument, the proposed stochastic input distance function will be ideal in carrying out efficiency analysis for microfinance institutions (Cope 2014). This research study will introduce the Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) application to quantify the allocative and technical efficiencies of selected microfinance institutions in China (Boyd & Solarino 2016). This method will be applied to approximate the actual stochastic Translog input distance function and compute technical inefficiencies.

Decomposing technical efficiency will involve separating the scale efficiency (SE) and pure technical efficiency (PTE). Reflectively, the PTE measures the degree of variation from a standardized production frontier off a Decision-Making Unit (DMU) (Bos & Millone 2015). This means that the pure technical efficiency explores the potential input reductions a DMU might achieve by integrating ideal production practices (Cronin 2014). The scale efficiency (SE) instruments the input usage reduction proportion realized by a DMU while functioning at a constant level of return to scale (Boehm & Hogan 2014). This means that the computation of decomposition will enable the researcher to identify factors that contribute to technical inefficiency.

Scope of the Research Study

This research study is focused on comparing and evaluating measurements of technical efficiency derived from the data envelopment analysis (DEA). As an instrument for measuring technical efficiencies in financial institutions, the DEA will facilitate the construction of an ideal performance benchmark using the observed bundles of inputs and outputs from the sampled firms. According to Biswal and Patra (2016, p. 134) “a DMU’s efficiency is a relative measure that compares performance to the best practice benchmark form the observed data on input-output combinations”.

This means that the DEA method will be applied first to estimate the measure of pure technical efficiency (PTE) followed by solving the DEA modeling using different constraints to obtain the technical inefficiency (Beskow, Check & Ammarell 2014). The third step will be the estimation of technical and pure technical efficiencies with the scale efficiency being derived as a ratio of pure technical efficiency and technical efficiency. The last step will be a sample investigation of DEA estimators and performing efficiency measure inference (Berlage & Jasrotia 2015).

The operational frameworks of microfinance institutions in China vary from those of best practice institutions across the globe due to variations in the policy environment. Across the globe, the microfinance institutions are often subjected to a myriad of private and government regulations (Berger 2015). However, the China-based microfinance institutions are subjected to stricter government policies that are restrictive and impact their operations and decisions.

In this study, the researcher intends to use the DEA conceptual framework to compare and evaluate the current technical efficiency in Chinese microfinance institutions (Bereznoi 2014). The technical and pure technical efficiencies will then be estimated using the DEA framework using different constraints. The derived technical efficiency ratios will be subjected to Seemly Unrelated Regression (SUR) to establish any differential characteristics in the technical efficiencies of microfinance institutions in China against the best practice models (Battisti, Dodaro & Franco 2014).

Research Organisation

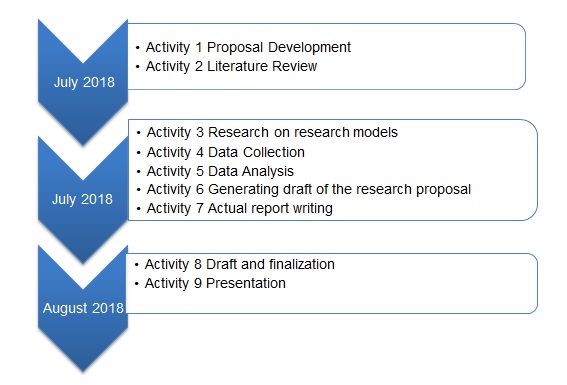

- Week 1: Research Commencement involved reviewing the research topic for relevance.

- Week 2 & 3: Choosing the case study. Choosing the case study microfinance sectors within China is expected to be challenging because the researcher is targeting all the regions.

- Week 4 & 5: Background research. Due existence of a lot of literature on the topic, this stage will be accomplished within the set time.

- Week 6, 7, & 8: Conducting the literature review. The research will perform a theoretical and empirical review on the topic to establish the current information available.

- Week 9, 10, & 11: Collecting data and analyzing data. Data collection and analysis will take three weeks since the researcher will have to examine several published datasets and use mathematical tools to analyze and interpret the same.

- Week 12 & 13: Research conclusion. The researcher will then compile the report and draw inferences based on literature review and statistical analysis (see chart 1).

Literature Review

This section of the research study explores the overview of the Chinese microfinance sector about the finance industry. The chapter traces the growth and reforms within the microfinance institutions within China and current programs in place to support the microcredit facilities targeting low and middle-income households. The section also presents empirical evidence from past case studies on the same or relevant topic. This chapter concludes by examining the literature gap and what should be done to fill the identified gap.

Historical Background of Global Microfinance Institutions

The global microfinance movement began in the late 1970s through organizational and individual grouping efforts. For instance, in 1971, David Bussau founded a microloan organization in Indonesia. The same year, Al Whittaker established a similar institution in Colombia (Bateman 2014). These individuals later founded Opportunity International, which was an organization that offered affordable loans to low and middle-income households in Canada, Australia, the US, and Great Britain (Baskarada 2014). By 1973, another worldwide institution called the Accion International was established to pilot a microcredit facility that targeted the poor households in Brazil (Bansal & DesJardine 2014). By the end of the year 1977, this institution had issued more than 850 loans with an average successful repayment rate of 94% (Banker, Mashruwala & Tripathy 2014). Over the years, Accion International has expanded into other regions such as Africa, Central America, the US, South America, and some parts of Asia.

Another interesting era in the development of microfinance facilities was in 1974 when a renowned entrepreneur and initiator of the Grameen Bank started an institution that would offer loans to start-up businesses in Bangladesh in the amount between $25 to 45 dollars (Banerjee & Jackson 2016). The success of this program catalyzed the formation of the Grammer Bank later in 1976. Over the years, the Grameen Bank has been able to provide microloans amounting to about $ 5 billion and is currently perceived as the best practice institution in the development and provision of affordable loans to poor and middle-income households (Bandura & Lyons 2015). In the 1980s, the microcredit program experienced a paradigm shift in its operational framework following the introduction of modifications directed at increasing effectiveness and efficiency (Baklouti & Baccar 2013).

During this era, regular financial institutions such as commercial banks began noticing the success and apparent feasibility of microfinance or microcredit institutions (MFIs). The positive feedback on microfinance institutions by low and middle-income household beneficiaries exposed the untapped potential of offering a viable lending system for the poor in a formal manner. In the 1990s, the microfinance institution experienced another rapid shift towards a globally recognized financial structure away from the previous grassroots approach (Bagnoli & Giachetti 2015).

In the last three years, many microfinance institutions have transformed into fully functional commercial banks. At the same time, many commercial banks across the globe have integrated microfinance services as part of their product charter to increase competitive advantage and built a large clientele base (Azzi et al. 2014). Moreover, many grass-root microfinance institutions are at the forefront in creating direct linkages with international, national, and regional markets. At its inception, the microcredit facility provided a standardized loan product that could not meet the needs of all brackets of low-income households (Ault & Spicer 2014).

For instance, the product did not include important insurance and saving instruments, could not support the building of assets, and exposed the lenders to all market risks. Over the years, the microfinance institutions have been grappling with the challenge of the best mix of strategies to be able to establish a reliable and efficient approach to the provision of a myriad of affordable and competitive microfinance services (Assefa, Hermes & Meesters 2013). In 2005, the United Nations made a declaration proclaiming this as the internal year of microfinance services and the Grameen Bank received a Nobel Peace Prize for its contribution to the growth and development of global microfinance institutions (Annim & Alnaa 2013).

Development of Microfinance in China

The inception of microfinance and microcredit facilities in China began in the 1990s and its development can be placed into three phases. The first phase was between 1994 and 1996 characterized by funding from soft loans and international donations void of any capital infusion from the Chinese government (Ashta, Khan & Otto 2015). During this phase, the primary focus was the possibility of replicating the Gammon Bank model in China. The second phase began towards the end of 1996 and the beginning of 2000 (Anney 2014). During this phase, the Chinese government began developing an interest in the provision of manpower, capital, and organization management practices. The government noticed the feasibility of poverty alleviation in China through the microcredit facilities within the microfinance institutions.

The last phase began towards the end of 2000 and is still ongoing (Angelucci, Dean & Jonathan 2015). The third phase is characterized by the development of Rural Credit Cooperatives to integrate microfinance services, especially in rural regions of China. At present, these rural cooperatives are the main credit providers to households in rural areas in need of microloans. Moreover, other international organizations such as IFAD, UNIFEM, and UNFPA have programs that support the provision of affordable microfinance services with the aim of agricultural development and poverty eradication in China. International non-governmental organizations such as USAID and WorldVision have also come up with affordable and flexible microloan services at the community level to help in fighting poverty (Anderson & Eshima 2013).

After prolonged research on the successes of the Gammon Bank microloan model, the Chinese government adopted a standardized microfinance operational model in 1994 called the funding poor cooperatives. This policy framework was implemented through the government-sponsored Institute of Rural Development through microcredit projects within six regions in China (Alshatti 2015). The success of these projects is expanding coverage of the institution to all other rural parts of China. Through public-private partnerships, the government of China was able to expand its microloan coverage. For instance, the China Qinghai Community Development project supplemented the government’s efforts towards eradicating poverty by pumping more than 14 million Yuan (Ammar & Ahmed 2016).

Over the years, the UN-funded microloan facilities have been successfully introduced in all 17 Chinese provinces and more than 48 counties (Allet 2014). Through the evaluation of the performance of these microloan projects, the Chinese government initiated an institution-based microfinance project in 1997. The project was aimed at supporting poverty alleviation programs by offering discounted lending for persons interested in microloans. These loans by heavily subsidized by China’s Central Treasury and their distribution was coordinated by the Funding Poor Cooperatives under the Agricultural Bank of China (Al-Shami et al. 2013). The program ended in 1999 and distribution activities were awarded to the Agricultural Bank of China in the same year. This model later experienced challenges associated with variations in the operational scale.

At the beginning of 2000, the Rural Credit Cooperatives commenced offering microloan services in the microfinance sector (Alhassan, Hoedoafia & Braimah 2016). At the start, these cooperatives were funded by the People’s Bank of China in the form of capital funds at affordable interest rates as part of the preferential costs. The launch for co-guarantee and microloans targeting the poor rural households was done in 2002. Over the years, these cooperatives have become the primary source of formal microloans for Chinese rural households (Alasadi & Al-Sabbagh 2015). At present, the Chinese microfinance organizations are segmented into;

- Non-governmental organizations running microfinance facilities to fight poverty through the provision of affordable and flexible microloan services. Among the notable institutions within this category are the Oxfam Hong Kong and the Poverty Alleviation Association (Akpala & Olawuyi 2013).

- Multi- and bilateral projects aimed at disbursing and managing donated funds within the regulations of donor-based organizations. Among the notable projects falling under this category are the UNICEF project, the UNDP project, the Xinjiang project, and the Quighai project among others (Akhavan, Ramezan & Moghaddam 2013).

- Microcredit projects operated by commercial and other financial institutions in China. For instance, the Australia-aided microfinance project managed by the Agricultural Bank of China was the main guarantor for loans provided to rural households by the Rural Credit Cooperatives (Aggarwal 2015).

- Specific microfinance projects are established by the government to operate and manage programs that provide discount lending to the poor. For instance, the myriad poverty eradication projects in Yunnan, Shaanxi, Sichuan, and Guangxi fall into this category (Adusei 2013).

Despite functional variations, these categories of microfinance institutions are controlled by different DMUs, depending on the lending regime and operational goal. For instance, the Rural Credit Cooperatives’ (RCCs) microloan services are not necessarily based on the poverty alleviation model. The lending model for the RCCs is based on the classification of the borrower households in different classes of credit rating, which is used to determine the microloan limit within the range of ¥1,000 to ¥20,000 (Adjei & Denanyoh 2016). The microloans provided by the RCCs must be repaid in full through a single installment arrangement towards the end of a loan cycle. Using a similar model practiced by the Grameen Bank, this lending scheme uses the group guarantee that ensures that the borrower is subjected to social pressure to repay his or her loan within the acceptable time range.

Chinese Financial System and the Rural Microfinance System

To comprehend the role of microfinance institutions in China, it is imperative to understand the Chinese rural financial and banking systems. Over the years, the financial sector has been boosted by the lending directed at farmers and the general agricultural industry (Adams & Vogel 2014). Moreover, policymakers at government and other regulatory authority levels have consistently encouraged the channeling of capital, especially in the agricultural sector to stimulate the raising of incomes in rural households and improve productivity (Ab-Rahman, Hassan & Said 2015). Between 2010 and 2016, the aggregate loans farmers are exposed to double. Although the policy changes are characterized by the motivation of credit cooperatives and rural banks to mold into financial intermediaries, there are strict government regulations that are restricting their expansion.

The policy-driven nature of these development initiatives has slowed-down lending practices. The reforms within the banking system in China commenced in the mid-1970s with the separation of the People’s Bank of China from the Finance Ministry (Abdulrahman, Panford & Hayfron-Acquah 2014). This was followed by the establishment of the China Construction Bank, Bank of China, and Agricultural Bank of China. The rationale for founding these institutions was to encourage diversification within the financial lending industry. The present banking system in China is categorized into four government-owned commercial banks, three specialized banks ten nation-wide commercial banks, several region-based commercial banks, rural and urban credit societies, investment and trust firms, leasing companies, financial companies, and international financial institutions (Adusei 2013).

Most of the financial needs of the poor and middle-income households are served by the Rural Credit Cooperatives, especially within the agricultural sector (Adams & Vogel 2014). Factually, by 1995, more than 90% of rural households in China were active members of the RCCs, which provided affordable and consistent microloans for personal and agricultural activities (Aggarwal 2015). The interest rates, management systems, deposit procedures, and loan terms of these RCCs have transformed by a pure government policy-driven approach to a more expanded commercial bank model (Ensari 2016). For instance, the RCCs collect deposits directly from farmers in addition to extending microloan support in productivity within the agricultural industry. They also hold the mandatory 20% deposits with the Agricultural Bank of China (Estapé-Dubreuil 2015).

Although the RCCs were empowered to have special interest rates on loans below the official government rate capping, they offer more or less the same services as other commercial banks and financial institutions. The only variation was a wider network of clientele stretching across the seventeen provinces, especially in rural areas (Founanou & Ratsimalahelo 2016). At present, these RCCs have branches in the grassroots in most village settings. The efforts to affect positive reforms in the RCCs commenced in 1984 to institutionalize democratic management, mass recruitment, and the creation of flexible operational frameworks (Guo & Guo 2016). The reforms in financial and banking sectors catalyze the changes within the RCCs such as reconstruction and separation from the Agricultural Bank of China to independent institutions under the supervision of the China Banking Regulatory Commission and the People’s Bank of China (Gupta 2014). For instance, the microloan scheme under these reforms expanded the RCCs loan access in rural households. However, the new system was characterized by a myriad of challenges such as financial losses accumulation and expanded demand for limited microloans (Forcella & Hudon 2014).

Agricultural Lending as a Function of the Microfinance Sector

As established in the previous section, the RCCs, ABC, and ADBC are the primary traditional microloan lenders in the Chinese agricultural sector. For instance, the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) is the main provider of microloans to rural cooperatives, agriculture-based enterprises, and village-based organizations within minimal financial services to individual households (Estapé-Dubreuil 2015). Although established in the 1970s to advance the rural empowerment policy, this institution was transformed into a commercial bank with expanded market coverage to include urban regions (Gras & Nason 2013).

On the other hand, the Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC) was established by the government as a policy-driven institution to provide loans for rural infrastructure, agribusiness, and commodity purchase. Moreover, the RCCs offer loans to businesses and individual households in addition to accepting deposits from this clientele base (Cooper 2015). At present, more than 35,000 RCCs are serving the 40,000 plus townships in China. The government has been effective in controlling these traditional lenders who are expected to follow strict development strategies and policy initiatives in their lending decisions or DMUs. As a policy persuasion, there is a general belief in China by policymakers that rural poverty alleviation is possible through the consistent infusion of affordable microloans (Cincotta 2015). Loans designed to make available production credit and improve infrastructure are also categorized in the policy-driven decision meant to boost productivity.

To solve the ‘three rural problems’; raising rural income, developing rural areas, and improving agricultural production, the RCCs are catapulted to make more loans available to the poor households in the rural regions, especially within the rural infrastructure and agribusiness projects (Dhitima 2013). As noted by Daidj (2016), the fixed assets investment and input expenditures within the agricultural industry increased from $135 billion in 2010 to $245 billion in 2015. At the same time, agricultural loans rose from $120 billion in 2010 to $278 billion in 2015. The substantial variation in the margin between agricultural expenditures and agricultural loans suggests that most of the agricultural loans are utilized for other non-agricultural needs such as healthcare, education, construction, and various business expenses (Guo & Guo 2016). For instance, the primary regulator of microloans called the People’s Bank of China suggests that usage of these loans includes “agricultural production; purchase of small farming machinery; services before, during or after agricultural production; or housing, medical service, education and consumption” (Ensari 2016, p 78).

The resent reforms within financial institutions in China have minimized the magnitude of institutional officials’ influence in the DMUs surrounding lending, which resulted in the expansion of nonperforming microloans in the early 2000s (Chinomona 2013). However, the RCCs and other agricultural banks are still tightly controlled by the government directives and Communist Party (Bos & Millone 2015). For instance, the Agricultural Bank of China is fully owned by the state and board members are government officials and Communist Party representatives. Moreover, activities within the ABC must be approved by the China Bank Regulatory Commission, which is a state organization. This means that agricultural banks and other financial institutions still consistently receive instructions from the government in line with policies that support affordable microloans (Ghosh 2013).

For example, in 2013, the government issued directives to the RCCs on how to control and expand the group lending program and group guarantee (Guo & Guo 2016). In China, capital risk and scarcity are not reflected by interest rates since they are preset by the central bank. Moreover, the RCCs credit rates are the lowest compared to other private lenders, which is an indication that the rates are lower than the market-clearing capping. Another interesting rule is that the RCCs can only operate within the boundaries of their home county to monopolize lending (Founanou & Ratsimalahelo 2016). However, the regulations allow a planned and government approved mergers of the RCCs, especially between a weak and strong institution.

Chinese Microfinance Institutions and Rural Credit Cooperatives

Since their inception in the late 1970s, the RCCs are the primary source of rural microloan financial systems in China, especially for low and middle-income households. The RCCs have launched a series of microloan products and co-guarantee systems consistently for the rural folks with their funding source originating from the PBC with backup from the central government. Over the years, the government has released more than $20 billion to absorb nonperforming loans to cushion these cooperatives (Guo & Guo 2016).

The RCCs also use customer deposits to finance lending, especially at the small scale level. However, over the years, the RCC microloan facilities have been liberalized to use a more or less similar lending mechanism as commercial banks in addition to the expansion of the clientele base beyond rural households. Since the RCCs service loans for the agricultural sector, their scope has expanded to offering lending services to agribusinesses and rural enterprises.

In the urban areas, the RCCs provide microloans to urban dwellers as capital for start-ups. By the end of 2014, 45% of the RCCs outstanding loans were from microloans issued to the agricultural sector (Jeffrey 2013). There is a formal formula for classifying the rural households before they are issued with a loan by the RCCs. Depending on credit rating, the average loan amount issued by the RCCs ranges from ¥1,000 to ¥20,000 (Gras & Nason 2013). The beneficiaries qualify for additional loans as many times as they want as long as the previous microloan is fully repaid.

In contrast, the Chinese microfinance institutions (MFIs) are solely focused on the rural regions, especially in the central and western parts of China. Through the provision of affordable micro-credit services to poor households, these programs are policy-based on alleviating poverty. The sources of funds for MFIs are many from the donor organizations in addition to domestic poverty alleviation funds (Cooper 2015). Through consistent provision technical and loan capital support, these donor organizations have catalyzed the expansion of MFIs across China. For instance, donor agencies such as Oxfam, AusAID, USAID, the World Bank, and UNDP have pumped billions of dollars in support of MFIs in China.

Under the domestic arrangements, the Chinese government has established the Poverty Alleviation and Development Offices to provide funding to MFIs from the year 1996 (Cincotta 2015). These offices are spread across provinces such as Yunnan, Sichuan, and Shaanxi. At their inception, the MFIs programs followed the same model as that of the Grammer Bank through group collateral. However, the reforms initiated by the government have made the MFIs more flexible in their operational model through the extension of the repayment period for loans from a weekly to a monthly program (Gupta 2013). Moreover, some MFIs in China are now liberalized to offer individual loans under the group guarantee model.

Microfinance Institutions in China

Evaluation of Chinese MFIs’ performance is complex and should integrate a reliability vantage point through a comparative review of different categories of these institutions. In this case, the vantage point will be the Grameen Bank model because of its best practices over the years (Dhliwayo 2014). The operational model for MFIs in China varies from that of the Grameen Bank model due to variations in the policy environment. For instance, the Grammer Bank model is characterized by loosened interest rates control, which enables this microcredit institution to package its credit facilities in a self-sustainable model. The policy environment where the Grameen Bank operates is liberalized through government facilitation of a self-governing approach towards the management of MFIs (Dhitima 2013).

This means that the Grameen Bank and other MFIs in its market are encouraged to develop collaborative financial institutions. The situation is different in China since MFIs are solely sponsored by a unit within the government in the form of state-controlled NGOs instead of fully fledge non-governmental organizations. This means that the Grammer microcredit model has an extensive reach as compared to the MFIs in China. Moreover, the Chinese policy environment is over-restrictive (Estapé-Dubreuil 2015). For instance, all NGO-based MFIs in China are required by the law to have at least a single government sponsor unit when applying to be registered under the social organization. The Civil Affairs Bureau has the responsibility of approving or declining such applications. This means that there are no pure NGOs offering microfinance services, despite having a more or less similar functional equivalence to pure NGOs (Daidj 2016).

The performance of MFIs has been impressive in China over the years. From the Funding Poor Cooperative (FPC) initiative in 1994, many microcredit projects have been launched with a low-interest microloan approach. International donor organizations have also established more than 400 regional microfinance programs in the western and central regions (Forcella & Hudon 2014). Through public-private partnerships, these programs have been organized into limited lifespan initiatives as opposed to the sustainability MFI model. For instance, in rural districts across China; where the majority of poor households are located, microfinance programs are initiated periodically with clear benchmarks for success after which the projects shift to other regions. As an example, the off-farm microloan facilities are periodical and limited to a specific region (Gervasi 2016).

However, these limitations are disadvantageous since they aggravate borrowing and operational costs. Moreover, the hostile geographic constraints have made it difficult for the MFIs to access their clientele base when processing loans on following up on repayment. Using a similar model as the Grameen Bank, the MFIs in China also disburse microloans to individuals using the group guarantee repayment plan (Ghosh 2013). Also, the primary focus of most microfinance institutions in China is to provide microloans to farmers or those within the agricultural industry. At present, urban clientele based such as the unemployed have not had adequate access to the MFIs services (Bos & Millone 2015) unlike the situation in the Grammer Bank where all poor households are covered.

Empirical Literature Review

A lot of research studies have been carried over the years to highlight the challenges, goals, and operational structures of microfinance institutions. To begin with, Ensari (2016) established that the main state-owned financial institutions in China are the least efficient as compared to privately owned financial institutions. In another study by Dhliwayo (2014) to examine the primary determinants of effective performance of banking institutions in China, the findings revealed that the net interest margin and value-added are dependent variables while return on equity, return on assets, and profitability are the ideal conventional measures.

This study also noted that foreign equity investment and bank listing are significant indicators of reforms that do not directly impact on the performance of financial institutions. In a study to compare risk organization and risk management practices within randomly selected banking institutions, Dhitima (2013) observed that there is no correlation between these measures. The author also noted that the content of the information for risk management organization and practice can be revealed through a DEA analysis framework. Unfortunately, the above studies were carried out in the context of commercial banks with a slight mention of MFIs.

In an attempt to understand the framework of microfinance institutions, a study by Daidj (2016) revealed that more than 300 million poor households have benefited from microloans in China in the last 5 years. The study also ascertained that these microfinance institutions play a vital role in the proactive development of financial capacity in rural households. However, the authors concluded that the MFIs are still struggling in China to balance social outreach and profit maximization. According to Forcella and Hudon (2014, p. 67), the microfinance institution is an organized movement that allows “many poor and nearly-poor households to have permanent access to an appropriate range of high-quality financial services, including not just credit but also savings, insurance, and fund transfers”. Moreover, Gras and Nason (2013) noted that profitability goals have been elusive for many microfinance institutions due to their short-term project nature. The study also ascertained that only 5% of MFIs in China are sustainable.

This means that 95% of the microfinance institutions in China are not efficient. The large margin of inefficiency has motivated a series of case studies using the outreach approach (Cooper 2015; Cincotta 2015; Chinomona 2013; Bos & Millone 2015) and financial efficiency model (Founanou & Ratsimalahelo 2016; Gervasi 2016; Ghosh 2013; Gasmelseid 2015; Gupta 2014; Guo & Guo 2016). Since financial services are an instrumental aspect of the operational module for MFIs in China, the efficiency analysis approach is justified in these past studies. A recent study by Guo and Guo (2016) found that financial capital, physical capital, and labor are determinants of MFIs’ financial efficiency in China. Daidj (2016) further contended that output and input specification affects the outcome of efficiency analysis of MFIs. Specifically, through a comparative analysis of 30 MFIs in China, this study concluded that none of the microfinance institutions could manage a high score in the combination of outputs and inputs as part of the efficiency matrix.

Several studies have also been carried out to examine the microfinance model in China. For instance, Founanou and Ratsimalahelo (2016) established that the microfinance model is characterized by organizational management, targeting a clientele base, operational scale, and mode, funding sources, and development projects. In a study by Ghosh (2013) to examine the scope of microfinance institutions towards eradicating poverty, the results indicated that a restrictive regulatory environment; uncertainty in the operation of the MFIs, and limited capacity to effectively manage finances impacted the level of efficiency. Other studies have covered threats, opportunities, policy and legal frameworks, market demand and supply, and how the microfinance movement in China has grown over the years. The studies established that most of the MFIs are inefficient in accomplishing the profit maximization and social outreach goals.

Literature Review Gap and Filling this Gap

Despite the existence of a lot of literature on assessment of efficiency within MFIs across the globe, there is little evidence of recent studies on the same within China. Therefore, this research study will fill this gap by performing a comparative review of the economic and operating efficiencies of microfinance institutions in China between 2013 and 2017.

Methodology

This section of the study aims at applying the stochastic Translog input distance function in estimating the allocative and technical inefficiencies and evaluating the operational efficiency scores for three MFIs categories in China. The allocative efficiency (AE) will measure MFIs’ ability to optimally use inputs to achieve the least costs at specified production technology and respective prices. On the other hand, technical efficiency (TE) will examine the MFIs’ ability to realize optimal outputs from a specified input bundle (Ahmed & Ahmed 2014), as summarized in the following formula.

Productive Efficiency (PE) = Allocative Efficiency (AE) × Technical Efficiency (TE)

Research Design

The study will rely on secondary data through a quantitative approach using distance functions to approximate the traits of multiple inputs and outputs void of price information in instances when the profit maximization and cost minimization hypotheses are inapplicable. The Stochastic Frontier Analysis will be used to compute a sample of Chinese MFIs in terms of allocative and technical efficiencies (Bell 2014; Chan, Fung & Chine 2013).

Variables and Data

The study will attempt to decompose and derive measures of efficiency across MFIs and best practice commercial banks in China. Specifically, the study has included four MFIs and 12 commercial banks. These microfinance institutions are PATRA Zahughan, PATRA Hunchun, Chifeng Zhaowuda Women’s Sustainable Development Association, and China Fund for Poverty Alleviation. Data on the financial and operational performance of commercial banks were obtained from annual reports and the Almanac of China’s banking and finance information between 2013 and 2017. Moreover, data on MFIs were mined from the Chinese official MixMarket.org for the same period.

The inputs in this study are the number of employees (x2), total assets (x1) while the gross loan portfolio (y) is the output. The input costs are denoted by c2 and c1, respectively. The c2 are expenses related to labor such as employee benefits and salaries while c1 are administrative and operating expenses (Bryman 2015). Computation of input price (p1) will involve summing administrative and operation expenditure then dividing the outcome by total assets. The input price (p2) will be derived by summing the employee benefits and salaries then dividing the result by the number of workers (Caruth 2013). This will be followed by computation of the cost shares (si) by summing the costs and dividing by a reciprocal of c1.

Findings and Analysis

Empirical Results

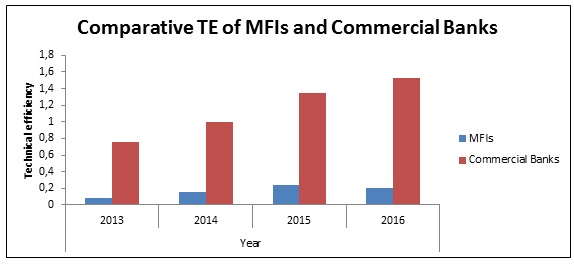

Comparative Technical Efficiency of MFIs and Commercial Banks in China

The researcher performed a comprehensive comparative review of the efficiency performance of the MFIs and commercial banks to establish consistency in the financial environment conditions that affect management and operating levels. The commercial banks have higher inputs than MFIs (table 1). However, labor cost share for MFIs is higher than commercial banks, which is an indicator of inefficiency compared to the outputs.

Table 1. Statistics of MFIs and commercial banks in China between 2013 and 2016. (Source: Self-generated).

Despite variations in inefficiency level over the period of the study, there is general existence of allocative inefficiency in MFIs and commercial banks in China alike, especially in terms of managing the inputs for optimal outputs (table 1).

The input distance function estimates were summarised in a tabular form (table 2). As earlier explained the function form has an impact on estimates consistency. The estimates coefficient for microfinance institutions in China is insignificant, which is an indication of similarity in technical efficiency levels in microfinance institutions and commercial banks (table 2).

Table 2. Estimates of the input distance function. (Source: Self-generated).

NB: „***‟ significant at 0.01, „**‟ significant at 0.05, „*‟ significant at 0.10

The differences in efficiency over the years were observed and the findings summarised in a tabular manner (table 3). ANOVA was used to establish the correlation between levels of technical efficiency in microfinance institutions and commercial banks in China. As captured in table 3, the results suggested that MFIs and commercial banks in China are not efficient technically.

Specifically, the commercial banks’ level of efficiency is 51%. On the other hand, MFIs recorded a 50% efficiency level. A further statistical correlation in the results indicated that levels of technical efficiency in Chinese MFIs and commercial banks are insignificantly different (p-value of 0.8307) (table 4). In general, Chinese commercial banks had a higher level of allocative efficiency as compared to MFIs.

For instance, the microfinance institutions’ allocative inefficiency indicated that these institutions have over-utilized the aspect of labor as input since their k function is less than one in all the years of study. Moreover, a graphical representation of the performance indicated that the MFIs’ performance was below the level of efficient labor and asset input utilization. The surveyed MFIs only managed an average of 20% allocative efficiency.

The allocative inefficiency in commercial banks in China fluctuated across the period of study (chart 2). However, it is important to note that the k function for commercial banks was equal to 1 in 2014 (table 3). This is an indication of a continuous effort to make adjustments in asset and labor input towards more effective operational modeling. In summary, it is to state that the Chinese commercial banks have a relatively stronger tendency to adjust the asset and labor inputs than the MFIs.

Table 3. Comparative summary of the asset to labor efficiency of MFIs and commercial banks in China. (Source: Self-generated).

NB: is the deviation of (P1/P2) market price ratio from (P1s/P2s) shadow price ratio, where P2 represents the expenditure in labor while P1connotes physical expenditure).

Table 4: ANOVA summary for technical efficiency between MFIs and commercial banks in China. (Source: Self-generated).

Evaluation of Technical Efficiency of MIFs in China

China is a developing country with a population of more than one and a half billion. A significant portion of this population consists of rural dwellers within the middle and low-income household bracket (Guo & Guo 2016). The low economic and rural demographic matrices make China an ideal environment for operating MFI programs. From their inception in the 1990s, the MFIs in China have had a myriad of challenges in their bid to implement microcredit projects and programs aimed at alleviating poverty. Due to a strict policy environment characterized by excessive government involvement, MFIs in China are struggling to achieve their goal of a wider and stronger impact in terms of social outreach in the backdrop of sustainable operations (Gupta 2014).

To understand the technical efficiencies of MFIs in China, the researcher carried out an estimative comparative analysis of efficiency scores among different MFIs using the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR). Specifically, the analysis was focused on establishing the primary factors that might explain significant variations among Chinese MFIs. The researcher concentrated on the scale efficiency and technical efficiency to gauge the MFIs on how they integrated the DMUs in balancing the input and output functions. The DEA function was used to calculate the efficiency by considering a Cadmus as the sample space, with each decision-making unit producing [y1, y2….yk] = m outputs using [x1, x2…xk] = n inputs. In this case, they are the output vector while x is the input vector. In using the DEA method, the inputs and outputs will be represented by the k column.

The inputs used are a risk, funding, and fixed assets. The rationale for the exclusion of labor as an input was informed by the small nature of MFIs, which means that it cannot significantly influence the return on investment or borrowers. The researcher used the gross loan portfolio to compute the MFI size instead of labor. Due to limited access to updated balance sheet data of Chinese MFIs, the researcher estimated the fixed asset variable as gross loan portfolio subtracted from total assets. The debt-to-equity ratio was used as the funding variable since it captures the primary sources that MFIs use to fund their programs or projects (Guo & Guo 2016).

Moreover, this ratio explains how funds are managed in terms of debt management. The variable of risk was included in the equation to examine the precautions taken by MFIs to cushion again bad loans. This means that the loan-loss provision ratio was used to evaluate the risk variable since it explains the perception of the MFIs towards the repayment ability of the borrowers. In this study, a higher ratio will signify low levels of confidence in the ability of borrowers to service their loans within the stipulated time.

The study surveyed 12 Chinese MFIs that had financial information in the MixMarket site. The descriptive statistics for Chinese MFIs, the Agriculture-based microfinance institutions dominated the other MFIs in the measures of return on investment and the number of active borrowers (tables 5 and 6).

Table 5: Statistical summary of agriculture-based MFIs and other MFIs in China. (Source: Self-generated).

Table 6: Summary of technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency and scale efficiency of agriculture-based MFIs and other MFIs in China. (Source: Self-generated).

Moreover, the agriculture-based MFIs had a larger deviation and average in all the variables (Table 7). The negative return on investment ratio in other MFIs in China signifies negative operating net incomes.

Table 7: Summary variables for the period of study

Discussion and Recommendations

The input distance function used to estimate the allocative and technical efficiencies of MFIs in China established that these institutions are generally inefficient. Moreover, the allocative inefficiencies varied across the period of study. When compared to commercial banks, the findings indicated that MFIs have wider inefficiencies in asset and labour inputs management. The data envelopment analysis using the nonparametric approach indicated that agriculture-based MFIs had higher technical efficiency levels than MFIs in the ‘others’ category. Due consistent government funding and risk cushion, the agriculture-based MFIs operate in a more competitive environment than other donor-funded microfinance institutions in China (Guo & Guo 2016).

The Seemingly Unrelated Regression used by the researcher to establish primary factors explaining significant variations in efficiency levels between agriculture-based and other MFIs confirmed that the former had better operational and financial structures than the latter. For instance, the agriculture-based MFIs have lower personnel allocation ratio and prolonged experience in offering microloan services than other MFIs (Gupta 2014). This is an indication that MFIs in the ‘others’ are less experienced or younger in managing large transaction volumes (Allet 2014). The findings also indicate that the agriculture-based MFIs have expanded operations in terms of assets, thus, more efficiency than other microfinance institutions. In terms of output variables, the results suggest that Chinese MFIs should target more women borrowers to improve on their pure technical efficiency (Al-Shami et al. 2013). Specifically, this recommendation is confirmed by the fact that women had impressive repayment scores in the Chinese MFIs.

Conclusion

The findings and conclusion of this research study have highlighted the challenges of MFIs in China’s face. The governmental intervention has created a restrictive policy environment that has affected the quest for these MFIs to maintain financial sustainability and ultimate survival. Moreover, limitations such as capping of the interest rates, geographical terrain, and restriction on clients to target have made it difficult for MFIs to adequately function and deliver microloans to poor and middle-income households in China.

Commercial banks in China have managed to realize a higher level of operational efficiencies as compared to MFIs due to lesser restrictions from the government. Since most agriculture-based MFIs are either operated or owned by the government of China, they have higher levels of efficiency than the other donor or group-owned MFIs. Specifically, these agriculture-based MFIs have access to significant funding from the state in addition to a risk cushion in the form of government writing off their bad loans and absorbing the cost.

Moreover, the agriculture-based MFIs are more flexible with longer operational experience as compared to younger and poorly funded microfinance institutions in China, thus, variations in efficiency levels. Based on the above challenges, it is to state that the establishment and optimal operation of MFIs in China is a technical affair since government interests and restrictive policy environment must be balanced. Moreover, financial sustainability is not easy to attain due to the short nature of microloan programs or projects. Also, interest capping has made loan pricing for the MFIs to be non-competitive.

Empirical literature confirmed this argument by stating that the greatest impediment to the establishment and operation of MFIs is the inability to attain financial sustainability. In China, many MFIs that are not owned by the government have to struggle to secure adequate funding, yet must remain as competitive as the state-sponsored counterparts. Moreover, the inflexible loan pricing regime as a result of the government ceiling on rates of interests has made the operational environment inefficient.

Area of Future Research

This research study has presented the current predicaments faced by MFIs in China. Due to challenges in accessing updated data due to the restrictive financial system in China, the researcher was not able to gather information on some variables comprehensively. Therefore, there is a need for further research that expands the output and input datasets to integrate other lending operation parameters. This proposed study might analyze the inefficiency challenge from the perspective of the borrower to provide inferences that could substantiate the current findings.

Reference List

Abdulrahman, UF, Panford, JK & Hayfron-Acquah, JB 2014, ‘Fuzzy logic approach to credit scoring for microfinance in Ghana: a case study of KWIQPLUS money lending’, International Journal of Computer Applications, vol. 94, no. 8, pp. 11-18.

Ab-Rahman, NA, Hassan, S & Said, J 2015, ‘Promoting sustainability of microfinance via innovation risks, best practices and management accounting practices’, Procedia Economics and Finance, vol. 31, pp. 470-484.

Adams, DW & Vogel, RC 2014, ‘Microfinance approaching middle age’, Enterprise Development & Microfinance, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 103-115.

Adjei, K & Denanyoh, R 2016, ‘Micro business failure among women entrepreneurs in 82 Ghana: a study of Sunyani and Techiman municipalities of the Brong Ahafo Region’, International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 1050-1061.

Adusei, M 2013, ‘Determinants of credit union savings in Ghana’, Journal of International Development, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 22-30.

Aggarwal, VK 2015, ‘Role of commercial banks in microfinance’, SAARJ Journal on Banking & Insurance Research, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 11-19.

Ahmed, SP & Ahmed, MTZ 2014, ‘Qualitative research: a decisive element to epistemological & ontological discourse’, Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 83, pp. 298-313.

Akhavan, P, Ramezan, M & Moghaddam, YJ 2013. ‘Examining the role of ethics in knowledge management processes’, Journal of Knowledge-Based Innovation in China, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 129-145.

Akpala, PE & Olawuyi, OJ 2013, Microfinance certification programme: a study manual, CIBN Press Limited, Lagos.

Alasadi, R & Al-Sabbagh, H 2015, ‘The role of training in small business performance’, International Journal of Information, Business and Management, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 293-311.

Alhassan, EA, Hoedoafia, AM & Braimah, I 2016, ‘The effects of microcredit on profitability and the challenges of women-owned SMEs: evidence from northern China’, Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 29-47.

Allet, M 2014, ‘Why do microfinance institutions go green? An exploratory study’, Journal of Business Ethics, no. 122, pp. 405-424.

Al-Shami, SS, Majid, IB, Rashid, NA & Hamid, MS 2013, ‘Conceptual framework: the role of microfinance in the wellbeing of poor people cases studies from Malaysia and Yemen’, Asian Social Science, vol. 10, pp. 226-241.

Alshatti, AS 2015, ‘The effect of the liquidity management on profitability in the Jordanian commercial banks’, International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 62-71.

Ammar, A & Ahmed, EM 2016, ‘Factors influencing Sudanese microfinance intention to adopt mobile banking’, Cogent Business & Management, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-20.

Anderson, BS & Eshima, Y 2013, ‘The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs’, Journal of Business Venturing, vol. 28, pp. 413-429.

Angelucci, M, Dean, K & Jonathan ZJ 2015, ‘Microcredit impacts: evidence from a randomized microcredit program placement experiment by Compartamos Banco’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 151-182.

Anney, V 2014, ‘Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: looking at trustworthiness criteria’, Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, no. 5, pp. 272-281.

Annim, SK & Alnaa, SE 2013, ‘Access to microfinance by rural women: implications for poverty reduction in rural households in China’, Research in Applied Economics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 19-41.

Ashta, A, Khan, S & Otto, P 2015, ‘Does microfinance cause or reduce suicides? Policy recommendations for reducing borrower stress’, Strategic Change, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 165-190.

Assefa, E, Hermes, N & Meesters, A 2013, ‘Competition and the performance of microfinance institutions’, Applied Financial Economics, vol. 23, pp. 767-782.

Ault, JK & Spicer, A 2014, ‘The institutional context of poverty: state fragility as a predictor of cross-national variation in commercial microfinance lending’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 1, pp. 1-41.

Azzi, A, Battini, D, Faccio, M, Persona, A & Sgarbossa, F 2014, ‘Inventory holding costs measurement: a multi-case study’, International Journal of Logistics Management, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 109-132.

Bagnoli, C & Giachetti, C 2015, Aligning knowledge strategy and competitive strategy in small firms’, Journal of Business Economics & Management, vol.16, pp. 571-598.

Baklouti, I & Baccar, A 2013, ‘Evaluating the predictive accuracy of microloan officers’ subjective judgment’, International Journal of Research Studies in Management, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 21-34.

Bandura, RP & Lyons, PR 2015, ‘Performance templates: an entrepreneur’s pathway to employee training and development’, Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 37-54.

Banerjee, SB & Jackson, L 2016, ‘Microfinance and the business of poverty reduction: critical perspectives from rural Bangladesh’, Human Relations, no. 1, pp. 1-29.

Banker, RD, Mashruwala, R & Tripathy, A 2014, ‘Does a differentiation strategy lead to more sustainable financial performance than a cost leadership strategy?’, Management Decision, no. 52, pp. 872-896.

Bansal, P & DesJardine, MR 2014, ‘Business sustainability: it is about time’, Strategic Organization, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 70-78.

Baskarada, S 2014, ‘Qualitative case studies guidelines’, The Qualitative Report, vol. 19, no. 40, pp. 1- 2.

Bateman, M 2014, ‘The rise and fall of Muhammad Yunus and the microcredit model’, International Development Studies, vol. 1, pp. 1-36.

Battisti, C, Dodaro, G & Franco, D 2014, ‘The data reliability in ecological research: a proposal for a quick self-assessment tool’, Natural History Sciences, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 75-79.

Bell, J 2014, Doing your research project: a guide for first-time researchers, 6th edn, McGraw-Hill, Berkshire.

Bereznoi, A 2014, ‘Business model innovation in corporate competitive strategy’, Problems of Economic Transition, vol. 57, no. 8, pp. 14-33.

Berger, R 2015, ‘Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research’, Qualitative Research, vol. 15, pp. 219-234.

Berlage, L & Jasrotia, NV 2015, ‘Microcredit: from hope to skepticism to modest hope’, Enterprise Development & Microfinance, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 63-74.

Beskow, LM, Check, DK & Ammarell, N 2014, ‘Research participants’ understanding of and reactions to certificates of confidentiality’, AJOB Primary Research, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 12-22.

Biswal, A & Patra, SK 2016, ‘Problems in operational efficiency and responsiveness of the microcredit institutions: a case study’, Indian Journal of Applied Research, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 196-201.

Boehm, DN & Hogan, T 2014, ‘‘A jack of all trades’: the role of PIs in the establishment and management of collaborative networks in scientific knowledge commercialization’, The Journal of Technology Transfer, vol. 39, pp. 134-149.

Bos, JW & Millone, M 2015, ‘Practice what you preach: microfinance business models and operational efficiency’, World Development, vol. 70, pp. 28-42.

Boyd, BK & Solarino, AM 2016, ‘Ownership of corporations: a review, synthesis and research agenda’, Journal of Management, vol. 42, pp. 1282-1314.

Braun, V, Clarke, V & Terry, G 2014, ‘Thematic analysis’, Qualitative Research Clinical Health Psychology, vol. 2, pp. 95-114.

Brière, M & Szafarz, A 2015, ‘Does commercial microfinance belong to the financial sector? Lessons from the stock market’, World Development, vol. 67, pp. 110-125.

Bryman, A 2015, Social research methods, 5th edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bumacov, V, Ashta, A & Singh, P 2014, ‘The use of credit scoring in microfinance institutions and their outreach’, Strategic Change, vol. 23, pp. 401-413.

Caruth, GD 2013, ‘Demystifying mixed methods research design: a review of the literature’, Mevlana International Journal of Education, vol. 3, pp. 112-122.

Chan, ZC, Fung, YL & Chien, WT 2013, ‘Bracketing in phenomenology: only undertaken in the data collection and analysis process?’, The Qualitative Report, vol. 18, no. 30, pp. 1-9.

Chinomona, R 2013, ‘Business owner’s expertise, employee skills training and business performance: a small business perspective’, Journal of Applied Business Research, vol. 29, pp. 1883-1892.

Cincotta, D 2015, ‘An ethnography: an inquiry into agency alignment meetings’, Journal of Business Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 95-106.

Cooper, L 2015, Small loans, big promises, unknown impact: an examination of microfinance, Web.

Cope, DG 2014, ‘Methods and meanings: credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research’, Oncology Nursing Forum, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 89-91.

Couchoro, MK 2016, ‘Challenges faced by MFIs in adopting management information systems during their growth phase: the case of Togo’, Enterprise Development & Microfinance, vol. 27, pp. 115-131.

Cozarenco, A, Hudon, M & Szafarz, A 2016, ‘What type of microfinance institutions supply savings products?’, Economics Letters, vol. 140, pp. 57-59.

Cronin, C 2014, ‘Using case study research as a rigorous form of inquiry’, Nurse Researcher, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 19-27.

Daidj, N 2016, Strategy, structure and corporate governance: expressing inter-firm networks and group-affiliated companies, Routledge, New York, NY.

De Melo, MA & Guerra Leone, RJ 2015, ‘Alignment between competitive strategies and cost management: a study of small manufacturing companies’, Brazilian Business Review, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 78-96.

Dhitima, PC 2013, Ten risk questions for every MFI board: a running with risk project expert exchange, Web.

Dhliwayo, S 2014, ‘Entrepreneurship and competitive strategy: an integrative approach’, Journal of Entrepreneurship, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 115-135.

Dimitrieska, S 2016, ‘How to gain competitive advantage in the marketplace’, Entrepreneurship, vol. 4, pp. 116-126.

Ensari, MS 2016, ‘A research related to the factors affecting competitive strategies of SMEs operating in Turkey’, International Journal of Business and Social Science, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 73-80.

Estapé-Dubreuil, G 2015, Management information systems for microfinance: catalyzing social innovation for competitive advantage, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle.

Forcella, D & Hudon, M 2014, ‘Green microfinance in Europe’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 135, pp. 445-459.

Founanou, M & Ratsimalahelo, Z 2016, Regulation of microfinance institutions in developing countries: an incentives theory approach’, Centre De Recherche, vol. 3, pp. 1-17.

Gasmelseid, TM 2015, ‘Empowering microfinance processes through hybrid cloud based services’, International Journal of Systems and Service-Oriented Engineering (IJSSOE), vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1-17.

Gervasi, M 2016, East-commerce: China e-commerce and the Internet of things, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, NJ.

Ghosh, J 2013, ‘Microfinance and the challenge of financial inclusion for development’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 56-79.

Gras, D & Nason, RS 2013, ‘Exploring the tension between strategic resource characteristics: evidence from Indian slum households’, Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1-15.

Guo, X & Guo, X 2016, ‘A panel data analysis of the relationship between air pollutant emissions, economics and industrial structure of China’, Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, vol. 52, pp. 1315-1324.

Gupta, S 2014, ‘Empowering women entrepreneurs through microfinance: a way to gender equality’, International Journal of Research in Management & Social Science, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 24-30.

Jeffrey, MC 2013, ‘“The silent revolution:” how the staff exercise informal governance over IMF lending’, The Review of International Organizations, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 265–290.

Jamali, D, Lund-Thomsen, P & Jeppesen, S 2017, ‘SMEs and CSR in developing countries’, Business & Society, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 11-22.

Waters, RD 2013, ‘Tracing the impact of media relations and television coverage on US charitable relief fundraising: an application of agenda-setting theory across three natural disasters’, Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 329-346.