Data Analysis

Revisiting Initial Design

This research project involved a mixed-method analysis based on a quantitative and qualitative data collection, analysis, and interpretation approach. Preliminary data collection strategies based only on semi-structured interviews proved inadequate and, in some ways, uninformative in terms of academic breadth. Nine respondents with direct ties to civil aviation were interviewed within the qualitative paradigm. These included three flight attendants, three pilots, and three flight mechanics, sometimes combined with pilots.

The semi-structured interview was a dialogue diagram with participants in which they were asked questions about anti-terrorism security on board the aircraft. These questions included descriptions of their experiences, clarification of some of the security strategies they use, and international differences they may have been aware of. Although the semi-structured interview method was beneficial, it could not provide a complete academic study and reflect representative data in isolation.

For this reason, it was decided to modify the design by adding a quantitative analysis section to expand the current project. In general, the quantitative research paradigm enables the discovery of relationships between variables, the identification of general statistical trends within a dataset, and the prediction of potential changes (Leavy, 2022). The motivation for this choice, in which qualitative research was modified by the addition of quantitative research before being transformed into a mixed-methods study, was driven by an attempt to collect as much relevant and useful data as possible from the perspective of the research question, which could find practical application in civil aviation. In brief, the point of the quantitative analysis in this project was to conduct an online survey [Web] among respondents who polled their opinions on aspects of counterterrorism security. The analysis involved using IBM SPSS software to provide descriptive statistics and conducting an inferential analysis to identify patterns between groups within the sample.

Mixed Research Paradigm

Neither quantitative nor qualitative paradigms alone could provide a reliable breadth of collected data. Nevertheless, combining them for this project proved to be the most advantageous strategy, as it simultaneously incorporated the benefits of both approaches. The current design is built on the convergent idea that data from both strategies are collected simultaneously and then subjected to analysis.

The clear advantage of this synthesis is to increase the overall validity of the study by mitigating the limitations of each approach, especially if the results reveal consistency (Leavy, 2022). Another motivation for choosing a mixed paradigm was the assumption that the results of each paradigm would be interesting to place within the framework of the other approach. For example, the results of semi-structured interviews can show intriguing insights when viewed within a quantitative analysis framework, and vice versa.

It should be understood that mixed-methods research is not rare in academic discourse but instead finds multiple applications. The widespread use of such a paradigm is particularly evident in the sociological and behavioral sciences, where authors attempt to study abstract and intangible patterns inherently subjective in perception (Leavy, 2022). It is fair to refute this by saying that anti-terrorism security is not subjective but based on rigid regulations and rules.

In fact, this is only partially true: different countries and airlines use their own regulatory frameworks, which creates a plurality of data. None of the individual research approaches could outline this data extensively, but their synthesis allows us to do so and uncover connections that can only be found by integrating paradigms. For this reason, a mixed design is a feasible strategy for the current research project.

Approach to Semi-Structured Interview Analysis

In contrast to quantitative research, which deals with numerical variables and combinations, qualitative data analysis can seem more complex. For this project, the data for this approach consisted of summarized responses from flight attendants, pilots, and mechanics to questions in semi-structured interviews, totaling three summaries. Since this data collection was conducted through written dialogue on social media, the raw materials did not require transcription.

Still, data did require some processing for the best possible analysis. For this purpose, all responses from respondents of the same category (e.g., three flight attendants) were compiled into a single text document, and semantically repetitive parts were deleted. For example, if all three respondents stated in different wording that they had not dealt with the threat of a terrorist attack on board, instead of listing all three responses, a single generalized, semantically indistinguishable response was created. In other words, the primary processing of the data involved intelligent verbatim transcription, allowing for more convenient analysis.

Analysis of responses to semi-structured interviews, including their summaries, is standardized through either thematic analysis or content analysis. Thematic analysis is based on carefully reading all the data and identifying common themes, ideas, and reflections given by different respondents (Braun and Clarke, 2021). For example, suppose respondents responded differently to the question of what strategies flight attendants use to identify potentially dangerous passengers.

In that case, thematic analysis can smooth out these differences and identify common themes. Two approaches to such analysis should be distinguished: inductive and deductive (Braun and Clarke, 2021). The inductive analysis assumes that the data determines themes; that is, themes can only be identified with a thorough review of the data.

In contrast, the deductive strategy relies on some preconceived themes to explore the data. For example, suppose some common patterns in civil aviation counterterrorism security emerge after a literature review. In that case, these are the ones that can be used to review the data. Regardless of the chosen approach, the thematic analysis proceeds with coding, resulting in the identification of themes.

The other side of semi-structured interview data analysis is content analysis. Traditionally, content analysis is conducted to identify common patterns for qualitative and quantitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2021). For example, this approach can identify the frequency of occurrence of particular words in a text or specific descriptions for particular categories. The same type of analysis can also determine the overall sentimentality of textual material by examining the content of the marker words.

Thematic analysis was chosen as the most appropriate and feasible approach to analyzing respondents’ responses in this research project. Analysis of the materials involves reading them carefully, identifying common patterns and keywords, deciphering codes, and categorizing them into individual components. The thematic analysis applied to the semi-structured interview data will determine how respondents of different professional backgrounds described aspects of counterterrorism security. Searching for common yet overarching themes will ensure that essential details are not overlooked in the analysis.

Approach to Online Survey Analysis

The quantitative paradigm of the current study was implemented through an online survey consisting of several blocks. The main questions of the questionnaire were based on a Likert scale, requiring participants to rate their level of agreement with a statement or to assign a level of significance to categories. The interpretation of such data is based on IMB SPSS statistical software, which allows all calculations to be performed automatically.

The general logic of the analysis can be divided into two stages, namely descriptive and inferential statistics. It was interesting to examine the common surface patterns in the dataset within the descriptive analysis. This is implemented by calculating frequency distributions and looking for measures of central tendency and variation (Mishra et al., 2019). While descriptive statistics provide an initial assessment of the data set, a more in-depth examination is required.

For this reason, turning to inferential statistics is a reasonable strategy. For this purpose, a parametric one-way ANOVA test was conducted to assess the significance of differences in responses between groups of respondents. By such groups, it is meant their professional backgrounds, in particular, whether flight attendants tend to rate passenger safety higher than pilots, as an example of a question in such an analysis.

One of the assumptions of the ANOVA is the continuity of the dependent variable, which is violated when choosing a Likert scale that measures responses on an ordinal scale (Blanca, Alarcón, and Bono, 2018). To ensure this assumption, it was initially necessary to compute new scale variables based on topic blocks. Thus, online survey questions about the experience of encountering threatening situations were combined into a single ‘Danger’ variable, which was created as a means of assigning ordinal values. This overcame the difficulty of assuming an ANOVA test, thus making it possible to use it for data analysis.

Hypothesis testing is also essential when conducting statistical analysis. Hypotheses are research assumptions that postulate relationships between variables or their behavior (Giacalone and Panarello, 2020). For example, in the context of a research question, one would hypothesize that respondents tend to choose risk management as their primary counterterrorism security principle more often, on average, than other suggested principles.

Another variation on the hypothesis is the assumption that the 1963 Tokyo Convention is the most frequent association when respondents are asked to think about such security regulations. Hypotheses are vital for inferential analysis because they set and guide the vector for processing and interpreting data. At the same time, such hypotheses are always accompanied by their opposite, namely alternatives (Giacalone and Panarello, 2020). Thus, some of the author’s initial preconceived ideas about the variables can be formulated into an alternative hypothesis, and the opposite hypothesis would be the null hypothesis, which postulates an inverse relationship.

An alternative hypothesis might be that mechanics, on average, were less likely to prioritize passenger safety as a top concern than other groups of respondents. Then the null hypothesis would be the inverse: the idea that there was no difference between the groups in preferences.

To evaluate the hypotheses, the significance level, alpha, is a numerical value that determines the probability of Type I error. In this case, the null hypothesis will be rejected, but it is true. Alpha determines the possible level of such an error, while it is clear that researchers should strive to lower it (Lakens et al., 2018). The optimal and most common choice for the level of significance is 05, which implies that there is a 95% probability that the results obtained are actually accurate.

Overall Representation of Results

One of the most critical steps in academic work is presenting results competently. For qualitative data, the results will be presented as textual findings for each of the themes found. For quantitative data, the results will be presented in tables, charts, and textual values, allowing fact-based judgments to be made about the variables. When reporting results in this manner, it is crucial to maintain consistency to ensure clear and competent communication between findings.

Results

Semi-Structured Interview

The first data collection phase consisted of semi-structured interviews with respondents in three professional roles: flight attendants, pilots, and mechanical engineers. One of the first themes found for all participants was an absolute acknowledgment of the rigor of airport screening that takes place. Crew members, like passengers, can be recruited, so they are also required to undergo pre-screening — they are not allowed to bring prohibited items on board. Respondents were unanimous that their screening experience was not significantly different from passenger screening, and they never observed any regulations being violated due to bias or leniency on the part of the screeners.

The entire crew is trained in antiterrorist protection before embarking on their first flight. One of the skills of such training is to resist a terrorist physically, that is, to disarm and apprehend him. The training also includes learning about the differences in counterterrorism security measures in the airspace of different countries.

Such training cannot be called a one-time thing, as the crew undergoes refresher training. A vital pattern seen here is the recognition that the rules, timing, and mechanics of such training likely differ for different airlines, but in general, they should be similar. The need for regularity of such training, as stated by respondents, is driven by the “ever-increasing number of terrorist attacks.”

A second important theme during the interviews was determining how different crew members detect a potentially dangerous passenger, that is, what gives them away. It was stated that respondents do not use profiling tactics but do examine passenger behavior. Identifying a potentially dangerous passenger through their behavior can be done by observing their emotions. Typically, individuals who are overly severe or tense, as well as those who are silent and vulnerable, are perceived by flight attendants as posing a danger.

It has been clarified that a risk check is an attempt to make contact with the person, and if they are not inclined to respond, it reinforces suspicion. Flight attendants tell pilots about all their suspicions via telephone. Still, the pilots do not use sensors to examine passenger behavior on board because they “have more important things to do” in the cockpit.

The third topic was a discussion of the crew’s strategies in the event of a detected terrorist threat. Even before takeoff, flight mechanics and the crew conduct a safety and security check to ensure all equipment is functioning properly. Further check-in is suspended if any threats are detected at this stage, and security personnel are invited on board.

No problem should be ignored, and the crew follows the informal three D’s rule: “Don’t Touch. Don’t Move. Don’t Leave Unattended.” An important note is that each crew member has their own area of responsibility during the inspection, and the board inspection is conducted according to the eye movement pattern. If a suspicious object is detected during the flight, the pilot informs the air traffic controllers, and together, they make decisions about landing at the nearest airfield.

The crew uses the three-question technique to determine if an object is truly dangerous. This involves determining the intention of the object left behind, the intention behind hiding it, and the potential for harm. If two of the three answers are positive, it is considered a dangerous object that could lead to an act of terrorism. In doing so, flight attendants ensure that all passengers are seated as far away from the location of such an object as possible and move it to a safe area if possible.

Each aircraft design has a different maximum safety zone in the event of an explosion, which depends on the aircraft type. The object is carried by a volunteer crew member accompanied by another crew member for backup. If carrying the object is impossible, flight attendants must surround the dangerous object with pillows, seat fragments, and plaids to create a protective screen. When a suspicious object is detected, full communication is always ensured between crew members, dispatchers, and management, so the responsibility is delegated.

In the case of a dangerous passenger, a verbal warning is initially given, followed by a written warning signed by the pilot if the passenger does not calm down. In extreme cases, when a passenger continues to exhibit defiant behavior, they must be arrested and isolated from others. Information about such a passenger is given to airport security at the landing airport so that he can be detained on the spot. It has been said that threats to the plane are made regularly, and they fall into two categories, green and red.

The difference between the two is understanding the passenger’s intentions: if they are jokes, the green signal tells them to watch. However, if the intentions are apparent, the red signal goes into effect: the information is transmitted to the pilot, and the passenger is detained. Unique checklists are used for all such procedures and are written for each likely situation.

If there is a hijacking threat, flight attendants must give the pilots a veiled signal so they can quickly contact security. The entrance to the cockpit, accessed through an armored door, is closed to all unauthorized personnel and remains open only to those who have entered the itinerary card before the flight. Notably, there are two strategies for dealing with terrorists, namely obeying their demands or physically resisting them, and it depends on the airline.

Online Survey

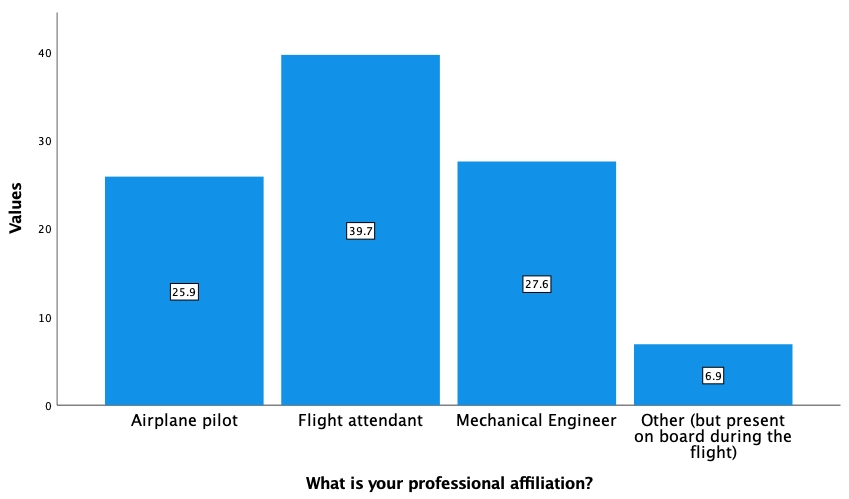

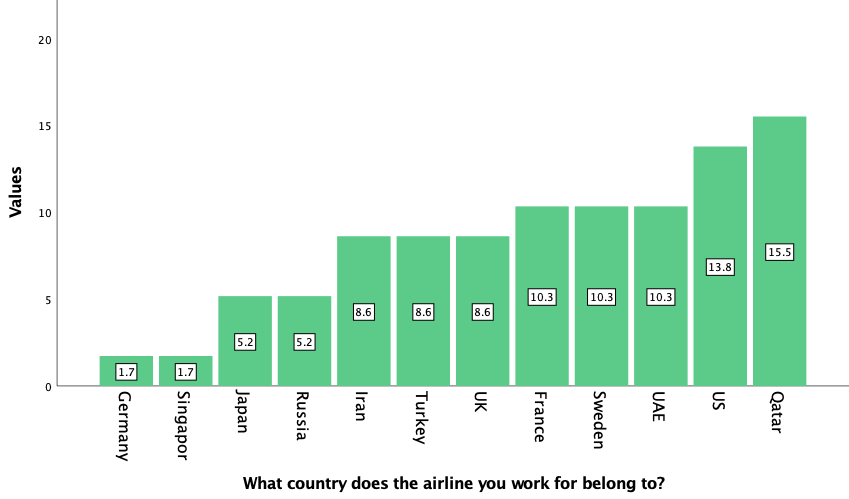

The sample collected (n = 58) consisted predominantly of flight attendants (39.7%) and was roughly equally divided among pilots, flight mechanics, and other participants, as shown in Figure 1. In terms of respondents’ geographic origin, the largest number of participants were from Qatar (15.5%, n = 9), the United States (13.8%, n = 8), and France, Sweden, and the UAE (each with 10.3%, n = 6). Figure 2 reports the other countries to which the respondents’ airlines belonged.

For the ANOVA test, respondents were divided into groups based on their professional role. The results (Table 1) showed no significant differences in how respondents answered the different blocks of the central part of the questionnaire. It follows that none of the groups were inclined to prefer any of the answers, and on average, general trends were true for all of them.

Accordingly, posterior tests are not required in this case. Table 2 shows the specific frequency values for the responses of the entire sample. Thus, approximately 2/3 of the respondents had never experienced an incident of terrorist acts on board, and approximately 45% said they had dealt with potentially dangerous passengers. Regarding the most crucial principle that respondents saw as the basis for counterterrorism security strategies, the majority (55.20%, n = 32) agreed that a systems approach was the most important. However, integration into international security systems was identified as the least important, with 51.70% (n = 30) of respondents disagreeing with it as a core principle.

Table 1: Results of the ANOVA test showed no significant differences between the groups

Table 2: Frequency distributions on the Likert scale

Respondents were also asked Likert scale questions to assess not only the level of agreement but also the level of importance of the suggested values. Table 3 reports that most respondents considered flight attendants (70.7%, n = 41) and pilots (65.5%, n = 38) to be responsible for anti-terrorism security, with flight engineers being assigned markedly lower importance in this regard. Notably, in the context of identifying the highest priority on board, namely, whose security is more critical, the passengers or the crew, respondents answered similarly on average: 51.7% (n = 30) and 44.8% (n = 26) agreed that passenger and crew security was an absolute priority, respectively.

Table 3: Frequency distributions on the Likert scale

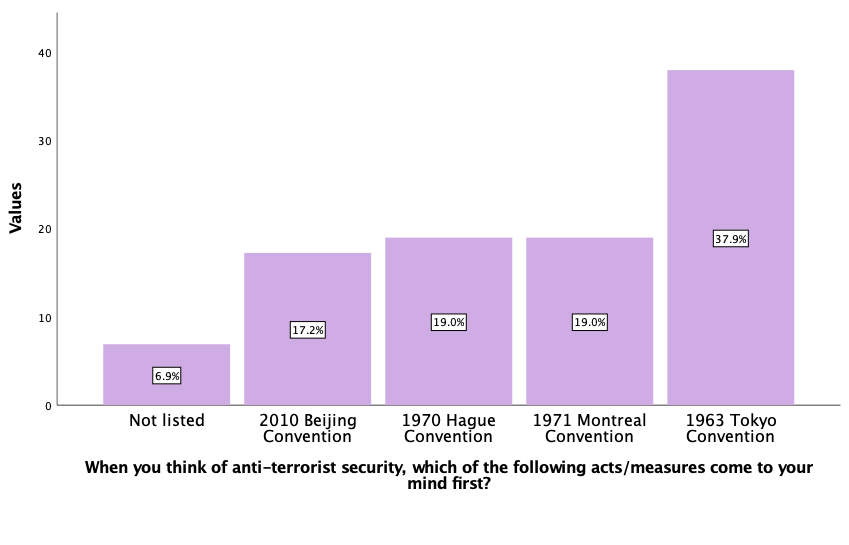

In the context of general questions that were not rated on the Likert scale, it was found that the 1963 Tokyo Convention was the most obvious association for respondents when discussing international antiterrorist aviation security regulations. The other most prominent conventions, as shown in Figure 3, had roughly equal ranks. When asked about profiling, approximately ¾ of the sample (74.1%, n = 43) responded that they did not use the technique. Finally, when asked if they would resist the terrorist or comply with his demands, 69.0% (n = 40) of respondents chose resistance.

Findings and Recommendations

This study explored critical strategies and gaps in civil aviation security and terrorism protection. With the ever-growing air travel market, the likelihood of terrorist attacks on board is increasing, as was confirmed by one of the interview respondents. Accordingly, there is an increasing need to improve existing tactics and strategies, including detecting potential pattern problems. To this end, interviews were conducted with flight attendants, pilots, and engineers, as well as an online survey of individuals involved in civil aviation.

The study had the advantage of being global because respondents belonged to different airlines from different countries worldwide. One of the main results showed that civil aviation is associated with extensive delegation of responsibility and communication, which means there is no possibility of making changes to the aircraft design that others will not notice in charge. The increased likelihood of such attacks in a growing market also leads to the need for ongoing training and retraining of employees, as noted in the interviews.

The crew responded effectively and reacted to any detection of suspicious items or passengers on board, continually using checklists and questioning strategies to identify the threat. It follows that they need to balance passenger comfort with a timely response to the problem: if a threat is detected, they will not ignore it, but will initially try to determine whether it poses a danger to the flight. In addition, preventive protection strategies include preventing unauthorized individuals from entering the cockpit, issuing verbal and written warnings to troublemakers, and closely monitoring passenger behavior. Notably, profiling tactics have yet to be identified among the data collection methods that are widely used. Likely, crew member observation of passenger behavior is not labeled with this term, but, in fact, has the same functionality.

When discussing further strategies to be undertaken by decision-makers to improve counterterrorism security, most respondents identified the systems approach as the essential principle. The basic concept of the systems approach is to view the system as holistic, hierarchical, structured, and multifaceted in its manifestations, with emergent properties (Hermans, 2019). In this approach, the output from a process leads to the formation of feedback that influences further inputs. In other words, the results of the tragic outcomes of a terrorist attack should not only determine its causes but also legitimately lead to the question “What was done wrong?” and “How to fix it next time?” With respect to civil aviation security, this means not making decisions dictated by individual predictors, but rather considering all components holistically.

For example, suppose it were known on the A321 flight over Sinai that terrorists were able to plant explosive devices in the baggage compartment. In that case, this does not mean that all other companies should immediately impose the strictest sanctions for baggage requirements on passengers overall. On the contrary, it means that such a problem represents a loophole open to terrorists that must be exploited and evaluated in the context of all civil aviation. Those in charge must make informed decisions to maintain the business’s profitability, the comfort of the flight, and safety. This could include implementing more advanced baggage screening methods, enhancing access control to aircraft structures, and conducting regular screenings of all airport employees.

Another attribute of the systems approach is the interconnectedness and openness of such systems. In the case of civil aviation, it follows that implementing positive change requires the participation of all parties involved who can contribute to decision-making. For example, suppose the need to implement stricter baggage screening systems is discussed. In that case, all stakeholders, from airport management to representatives of the passenger community, should be invited to discuss the benefits of doing so. The views of everyone in the systems approach must be considered and heard so that the final decision is balanced, comprehensive, and not destructive.

Interestingly, the choice of the majority of respondents —a systematic approach —fits well with the results of the interviews, in which participants stated the existing system of assigning responsibility. Any decisions made by employees are typically controlled by their management, indicating the existence of a hierarchical structure (Hermans, 2019). To date, the civil aviation system is based on some of the fundamentals of the systems approach, but has room for improvement. For example, implementing an independent security audit for every flight could be a smart strategy for total anti-terrorism security, although it would undoubtedly entail increased wait times and costs.

An extremely intriguing result was obtained regarding the prioritization of security on board. It could be said that respondents were unable to give a definitive answer as to whose safety was more critical: passengers or crew. However, roughly the same number of votes were cast for each option, proving the impossibility of a specific choice. This may be because both passengers and crew find themselves in the same position in a terrorist attack, so it is impossible to save the lives of one to the exclusion of harm to the other.

On the other hand, the result may indicate that the crew members who form the basis of this sample view passenger safety on the same level as their own lives, suggesting the ability to make selfless decisions. This result also confirms the need for a systems approach that guarantees the interconnectedness of all system elements. However, it is still interesting to determine this pattern if respondents could not assign passengers and crew to the same categories of importance; that is, they would be forced to make a choice.

Limitations and Opportunities

This research project yielded excellent results regarding the implementation of anti-terrorism security policies on board civil aviation. Meanwhile, it had several limitations, one of which was a challenge to further develop the entire project. First, the sample sizes for both data collection approaches needed to be bigger, which could have led to bias in the results. Second, the online survey implied anonymity in data collection, and there is no guarantee that only individuals with civil aviation-related interests participated. At the same time, there is also no guarantee that the same respondent only participated once.

Third, some of the information provided by the flight attendants was deliberately withheld at the time of the interview, which appears to have been a trade secret and subject to an NDA obligation. It needs to be determined exactly what the respondents concealed and how it may have influenced the results. Nor should one ignore the Hawthorne effect, which could lead to unconscious distortion of the results due to direct interaction with respondents.

Addressing the limitations described above is part of further work on this research project. At the same time, several modifications are suggested that would expand its scope. This refers to adding variables that could lead to statistically significant differences in response. For example, age, gender, or ethnicity are used to observe how these factors affect perceptions of antiterrorist security. Moreover, adding a specific airline affiliation factor to the analysis would also help investigate precisely what differences exist in providing this security.

Recommendations

One of the key recommendations based on the findings of this analysis is the need to implement a systematic approach across the board that addresses most of the problem areas in civil aviation. Such a solution is expected to favorably modify existing organizational structures to achieve interconnectivity, open communication, and accountability. At the same time, airlines must develop policies for regular employee training and retraining to continually improve counterterrorism skills. The intriguing result that ¼ of respondents would make concessions to terrorists suggests a lack of unambiguity for crew members in this context.

Airline regulations should be structured so that, in a critical moment, the crew does not hesitate and clearly follows the regulations, demonstrating the highest stress tolerance, on which the lives of all people on board depend. It is worth emphasizing that if integration into international aviation security systems has been chosen as one of the least essential principles of antiterrorist security, airlines should invest in developing their own reliable and sustainable regulations, while recognizing and appreciating the experience of their international competitors.

Reference List

Blanca, M.J., Alarcón, R. and Bono, R. (2018) ‘Current practices in data analysis procedures in psychology: what has changed’, Frontiers in Psychology, 9, pp. 1-12.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2021) ‘Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches’, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), pp. 37-47.

Giacalone, M. and Panarello, D. (2020) ‘Statistical hypothesis testing within the generalized error distribution: comparing the behavior of some nonparametric techniques’, Book of Short Papers SIS, pp. 1338-1343.

Hermans, T. (2019) Translation in systems: descriptive and systemic approaches explained. London: Routledge.

Lakens, D., et al. (2018) ‘Justify your alpha’, Nature Human Behaviour, 2(3), pp. 168-171.

Leavy, P. (2022) Research design: quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York: Guilford Publications.

Mishra, P., et al. (2019) ‘Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data’, Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia, 22(1), pp. 67-72.

SL (2021) One-way ANOVA in SPSS Statistics. Web.