Introduction

Like many art forms, the architecture may be viewed as a way of mirroring the specifics of national identity. The identified phenomenon is especially evident in Asia, where different cultural traditions mix. Incorporating the concepts of colonisation and following independence (Singapore) with the trials and tribulations of a people traumatised by war and cataclysms (Japan), the architecture that makes up the background of Asia, the grandeur of the urban landscape, creates the impression of a search for a lost identity.

Since World War II and the continuous conflict with Europe and America, as well as the military confrontation, witnessed during 1939-1945, Asia has been trying to revive its culture and regain the national identity that was lost at the time. Some of the states went even further in their endeavour to regenerate the national cultural traditions. Japan, for example, focused on designing an architectural approach that could surpass Western achievements and, therefore, become a tool for taking over Western culture, at the same time heralding a new era in the economic development of Japan.

Singapore, in its turn, has been struggling to find in truth a unique manner of artistic expression in architecture because of the Japanese and the British influences under which it had existed up until 1965. The drastic difference in the experiences of Singapore and Japan predisposed the difference in their approaches to galvanising the process of searching for their national identities in the post-WWII era. As a result, the artistic choices that the Japanese and the Singaporean architects made when creating their works clearly have very few similarities. The identified phenomenon can be witnessed across Asia: though the propensity for the search for national identity is evident in most Asian countries, the approaches in architectural expression are strikingly different. Nevertheless, both states managed to retain their culture and restore their national identity.

What Is National Identity?

The concept of a national identity is rather broad and, therefore, rather difficult to define in exact terms. In fact, the process of locating a national identity within the boundaries of a single state or even a single culture is likely to spawn numerous conflicts and confrontations due to the differences in the intrinsic understanding of the subject matter by the residents. Additionally, the concept of a nation and national identity is often confused with ideas of nationalism, which limits the opportunities for the state and its residents to accommodate to the changes in the political realities.

Traditionally, the concept of the national identity is defined as the sense of unity within a nation, which manifests itself in a unique language, a specific set of traditions, authentic culture, etc. However, the suggested interpretation of the phenomenon of national identity can be deemed as rather broad. Another way of understanding the concept of the national identity involves viewing it as a combination of “continuity over time and differentiation from others.” The suggested approach, however, begs the question whether there is a way to draw the line between the “others” and the members of the population who are defined as the nation. In the context of architecture, the idea of national identity is embedded in the national memory. Since architecture is supposed to represent a specific era or event, or certain events that marked the identified time period, it should be viewed as a part of the national identity. Thus, the art forms related to the specified area can be viewed as a means of reconstructing the national identity and representing the culture of the state in which they were built.

Case Study

Case Study 1: Singapore

The process of redesigning the architecture of Singapore started as soon as the state seceded from Malaysia. Forty years was enough time for the state to evolve into a country with a distinct and unique economic strategy, sensible policies in both the home economy and foreign affairs and an unbelievably high GDP. The promotion of free market principles in the trading process has also contributed to the rapid progress of Singapore. However, the economic and political success was overshadowed by the fact that, while fast, the pace of the state’s progress was still slower than that of the globalisation process. Unless the Singaporean authorities had come up with a solution that could enhance the speed of the process, the state could have lost an opportunity to gain a share of the global free market. The following rivalry between different regions of Singapore nearly turned out to be detrimental to the further progress of the state since it ruined the chances for successful cooperation between the regions and, instead, focused on the rivalry between them. The focus on preserving the national identity through branding the state’s historical landmarks was an automatic response to the effects of gglobalisation.

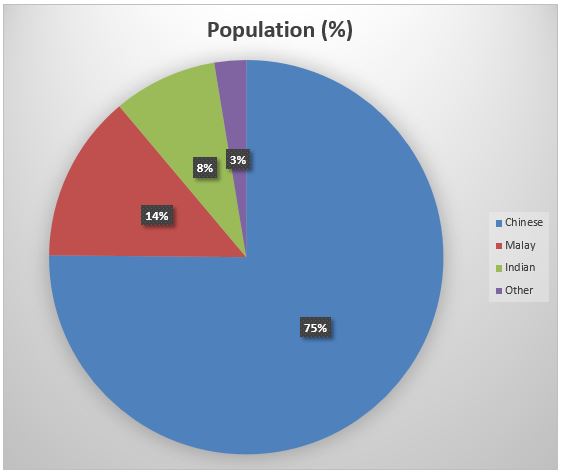

In its attempts to revitalise the national identity, the residents of Singapore realised soon enough that there is a direct link between tradition and national identity. For instance, the high level of cultural diversity that could be witnessed in Singapore at the time (see Fig. 1) allowed merging the concepts of the Asian identity and the Singaporean identity into a cohesive whole.

It should be noted, though, that the architecture of Singapore was also extensively influenced by the postmodernist tendencies of the 20th century.

Esplanade Theatre and Singapore’s National Identity

When considering the artefacts that can be deemed to be specimens of the Singaporean culture, one must mention the Esplanade Theatre as one of the most graphic representations of this kind. In fact, it can be considered the spatial interpretation of the economic and cultural changes that Singapore was undergoing at the time it was built.

At present, the building includes two round space frames with triangular glass ornaments at the top. The sunshades, in their turn, create an environment in which the audience can enjoy the landscape without the ssun-blockingtheir view. The innovative decisions made to redesign the building in the 20th century can be considered a compromise between the necessity to update the architecture and complaints about the style changing toward the Western aesthetic. As a result, aluminium sunshades were introduced as an additional feature of the new design. Furthermore, the shades allow adjusting the amount of sunlight so that visitors can get a proper view of the area, including the Esplanade and the waterfront. Although the use of neo-tropical elements in the building transfers the audience to an era that came much later than the artwork had originally been created, the identified elements add a unique sense of simplicity and nostalgia for modernism to the luxurious background, thus creating a delicate balance. Therefore, the building represents an authentic mixture of the Singaporean culture and the architectural traditions of the rest of the ethnicities by which the target area is represented.

Similarly, the shape of the building can be viewed as inconsistent with the local cultural traditions. For instance, the introduction of the glass elements into the overall design of the building, particularly, in its central part, can be viewed as a digression from the traditional concept of Singaporean architecture. However, taking a closer look at the building, one will have to concede that the inclusion of the glass elements allows the form to coexist with the function. Similarly, the use of timber and banana, which create a “fish-scales” pattern, should be interpreted as not only an attempt to smash the traditional and innovative approaches together in an endeavour to be original but also a way to reduce the impact of heat, which is typical for tropical areas like Singapore.

The wooden struts, as well as the wood tones, contribute to the creation of an atmosphere of the tranquillity that is embedded in Eastern philosophy. The hall owes its Asian flair to Michael Wilford, who contributed significantly to the design of the building and the choice of the materials. It is remarkable that the traditional elements reminiscent of Eastern philosophy and the local traditions were suggested by the Singaporean government. As a result, both the interior and the exterior were shaped to remind the beholder of the local culture and traditions, whereas the foundation for the building was made of modern materials so that quality standards could be upheld.

As Vikas, the DPA director,explained after the construction was finished, the building was supposed to embody the propensity for the Asian culture to evolve into something completely unique. As a result, the building does not resemble the typical Western approaches to architecture since it is not supposed to. Instead, it is a unique thing in itself and a landmark of the evolution of architecture in the tropical landscape of the Eastern culture.

Case Study 2: Japan

Post-War Japan: Metabolism in Architecture

Although the same tendency to revive the elements of the Japanese culture can be traced in the local architecture, the reasons for the Japanese people to go back to the traditional forms of expression and the revival of their culture had a much darker back-story than that of the Singaporean population. Torn apart by war, Japan was literally in shambles by the 1950s. Suffering a tremendous defeat, Japan decided to delve as far into the culture foisted onto it by West as possible, thus causing the national identity and the Japanese culture to resurge.

More to the point, drastic social changes affected the Japanese national identity to a considerable extent. In contrast to Singaporean society, which was influenced significantly by other cultures that dominated the Singaporean one for several centuries running, the Japanese population was literally in shambles after the Second World War. Therefore, the sense of a national identity vanished without a trace, leaving the Japanese population to wander in search of the means of self-expression.

It would be wrong to assume that the changes to Japanese architecture had no points of contact with the alterations that the Singaporean population experienced. Aside from the trend to re-establish Japanese traditions, there was a noticeable tendency to support the Metabolism movement by creating artworks that were very much in vein with the artistic style in question. For instance, the World Design Conference in Tokyo in 1960 showed that the Japanese culture was open to exploring futuristic ideas that challenged the cultural traditions of the state. As a result, the prerequisites for shaping a national identity that was comfortable with the influences of other states were created. Particularly, artists such as Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa and Fumihiko Maki should be credited for building an environment in which new life could be breathed into Japanese architecture.

It could be argued that the concepts of Metabolism could not add much to Japanese architecture since the movement had flaws at its very foundation. Indeed, according to Schalk, the proponents of the movement suggested the concept of the resilience utopia that could not possibly be sustained by the realities of the post-WWII world. However, it could be argued that the introduction of Metabolist elements into the context of Japanese architecture could work as a tool for bridging the West and the East after a long and convoluted confrontation that had exhausted both parties. Indeed, according to the existing evidence, Metabolists “strove to mediate between an urbanism of large technical, and institutional infrastructures and the individual freedom with an architecture of customised cells and adaptable temporary configurations of dwellings, which could expand and shrink according to need.”

Therefore, the philosophy of Metabolism was not only inevitable but also crucial to the further evolution of the state. Predisposing the further attitude of its residents to the idea of introducing the elements of other cultures into the environment of their architectural traditions, the identified innovation can be viewed as an essential step in the state’s progress.

Furthermore, the technological innovations that were the driving force behind not only the cultural progress but also the economic growth and the intensity of social progress could be promoted in the context of the Japanese environment with the help of the Metabolism movement. Allowing the representatives of the Japanese culture to accept the alterations of their traditional environment and interactions and making the process of a cultural integration considerably simpler, the Metabolist movement should be viewed as one of the essential factors in addressing the psychological and cultural crisis that enveloped the country at the time. In other words, Metabolism in architecture, as well as in art in general, became a coping technique for Japan, which had a burden of economic and political issues to address, in contrast to Singapore. It helped manage the tragedy of losing the national identity, which the Japanese population experienced at the end of the WWII.

Metabolism as the Tool for Restoring the National Identity of the Japanese Population

As stressed above, the principal tenets of the Metabolist movement created prerequisites for handling the trauma of losing the national identity completely. Furthermore, it created the premise for building a new one that could be more resilient toward outside influences and survive a major crisis. A closer look at the way in which the phenomenon of Metabolism allowed altering the landscape of the Japanese artistic environment will show that the movement, in fact, allows viewing art from two perspectives, i.e., the cultural origin of the artwork and the need to create a spatial environment that can be flexible enough to accept change. For war-torn Japan, the oopportunityfor building its cultural framework from scratch and making it more resilient toward outside influences was a crucial stage in rebuilding its national identity.

Comparison: Reasons for Difference

As the analysis carried out above has shown, there is a significant difference between the way in which architecture as an art form developed in Singapore and Japan. Particularly, the socio-political factors need to be revisited first when addressing the issue. As explained above, the geographical isolation of Singapore, as well as the impact of British rule that the state had been under up until the 20th century, allowed for rather rapid progress yet inhibited the evolution of a national tradition.

By adding the elements that embodied the topical characteristics of Singapore, the architects made the style distinct and recognisable. The emphasis on the ergonomics of the houses built based on the specifics of the local climate can be deemed as a reference to the Malayan culture, particularly, their houses that were indigenous to the people inhabiting the area. One must admit, though, that the current interpretation of architectural traditions is influenced heavily by the British colonial style. The combination of the historicist and the deconstructivity principles that can be viewed as an integral part of the postmodern art serves as the foundation for creating unique artwork.

Japanese architecture, in its turn, suffered irreparable damage during WWII. As a result, Japanese people had to reconstruct their national and cultural identity from scratch. Surprisingly enough, the new approach toward the development of culture allowed incorporating a range of Western elements, at the same time making artwork, especially in the domain of architecture, easily recognisable and admittedly original. The changes in the Japanese cultural environment also incorporated the indigenous architectural style and the influences of the West. As a result, the opportunities for embracing the globalization movement and retaining the cultural identity at the same time were created. Therefore, the architecture of both Japan and Singapore portrays the compromise between keeping traditions and exploring new opportunities.

Conclusion

The Eastern culture, in general, and its architecture, in particular, has been evolving in an environment that was filled with social and economic obstacles. Posing a threat to the existence of the national identity of the specified nations, the external forces affected the sense of national identity in both states, the Singaporean acquiring a range of international features, and the Japanese having been completely destroyed. Nevertheless, choosing their own path of development, both Japan and Singapore managed to survive the crisis and restore their architectural traditions.

The pathway to change was admittedly complicated, as a range of artworks in Japanese and the Singaporean architecture shows quite graphically. Acquiring numerous elements of the Western tradition, these buildings, however, also represented the propensity among the representatives of the specified nations to work towards the revival of their culture. Incorporating elements of the Eastern and the Western traditions in an attempt to marry the two philosophies, artists from both states made an array of important changes. The promotion of the concept of a form being directly connected to a function is, perhaps, among the essential concepts that the alterations to the specified cultures promoted. In addition, the significance of technological progress, which the specimens of the new architectural styles in Singapore and Japan emphasise, also needs to be credited as an essential change.

Therefore, despite years of desolation and destruction that Japan suffered and the influence of British rule that Singapore experienced, both countries managed to restore their national identity and reflect it in art, particularly, in architecture. While strikingly different, the two cultures bear a distinct resemblance to each other. They echo the key events of the 20th century, the struggle to maintain national integrity, and the need for artistic self-expression. At the same time, they point to the possible paths that Japanese and Singaporean residents may choose for their further progress and ensure the safety of the people’s national identity.

Bibliography

Guibernau, Montserrat. The Identity of Nations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Kam, Ronald L. K. “Singapore: Identity and Architecture.” Academica. Web.

Penrose, Jan and Richard C. M. Mole, “Chapter 16: Nation-States and National Identity.” In The SAGE Handbook of Political Geography Nation-States and National Identity, edited by Kevin R. Cox, Murray Low, and Jennifer Robinson, 271-285. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2008.

Quek, Raymond. “The Mirror of Territorial Identity in Singapore Professional Architecture 1923-1969: Colonialism, Nationalism, Separation, and Independence.” Academica.edu. Web.

Schalk, Meike. “The Architecture of Metabolism. Inventing a Culture of Resilience.” Arts, vol. 3 (2014): 279-297. Web.

Seligmann, Ari. “Japonisation of Modern Architecture: Kikuji Ishimoto, Junzo Sakakura and other precursors.” Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 31, Translation, 177–187. Auckland: SAHANZ, 2014.

Wilson, Christopher S. Beyond Anitkabir: The Funerary Architecture of Atatürk: The Construction and Maintenance of National Memory. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Zszczyrba, Szymon Lukas. Human and Nature Symbiosis: Biomimic Architecture as the Paradigm Shift in Mitigation of Impact on the Environment. Oxford: Miami University, 2016.