Executive Summary

Being characterised by its innovative approach, Nestlé has been popular since the day of its creation. Even the imminent change in the information management ensuing from the technological breakthrough of the 21st century did not make the organisation shrink away from the spotlight.

Nowadays Nestlé remains a big name in the food industry, and the company obviously owes its success to the specific management approach that it adopts in order to market its services to the target audience, as well as the approach towards motivating the staff towards a better performance and a set of strategies aimed at innovativeness.

However, it seems that Nestlé should put a stronger emphasis on its network strategy used as the framework for its R&D approach, as it allows for making the company even more conspicuous in the realm of the global market and attract new customers.

Nestle Management Introduction

If there was a list of the companies that should have become a household name decades ago, Nestlé would definitely top it. Founded in the 19th century (1866, to be exact) (Ryland 2013), the organisation evolved very soon and very smoothly into a powerful conglomerate with millions of customers, thousands of opponents and very few honestly successful rivals (Boyd 2012).

Nestlé has never evolved intermittently; apart from the 2010 crisis (Coombs & Holladay 2011, p. 411), the company has been known for its steady pace of development. As a result, Nestlé remains unmatched to date in terms of its power, marketability and unforgettable brands.

While some assume that a set of clever marketing strategies is the key to understanding the company’s efficiency, and others believe that the company’s HRM system is the superior element that defines its triumph, it will be reasonable to say that Nestlé owes its success to marketing, R&D approach and leadership strategies. When combined, the three serve as a powerful enhancer for Nestlé’s further progress (Rae 2007).

Company Evaluation

Even though the progress of Nestlé has been comparatively smooth, the transition from one type of environment into another one, i.e., the transfer from the traditional market into the globalised environment, has had a major impact on Nestlé. The organisation was to be inured to facing extremely harsh competition and tread the precarious track of creating international partnerships.

It would be wrong to claim that Nestlé’s leaders never carried out similar steps before; it was that the relationships of such type were not common for the organisation and, thus, viewed as precarious at first (Ryland 2013). However, a closer look at the assets and problems that the company displays in the global economy realm will reveal that Nestlé, in fact, entered the global market quite prepared.

SWOT

A brief SWOT analysis of the organisation will reveal that the company’s ability to incorporate modern tools into its production and marketing process, as well as the aptitude for galvanising the employees with new ideas, is an obvious asset of Nestlé.

Table 1. SWOT Analysis of Nestlé

Porter’s five forces (Hales 2001).

- Threat of new entrants: low

Nestlé being a powerful competitor, new entrants rarely succeed. - Threat of substitute goods: high

What used to be the clones of Nestlé’s products have developed into high quality substitutes. - Bargaining power of suppliers: high

Nestlé has developed strong relationships with a range of suppliers. - Bargaining power of customers: high

The quality of Nestlé’s products defines its position in the global market. - Competitive rivalry within the industry: low

Holding colossal power in the food and beverage industry, Nestlé has very few competitors.

Value chain

Picture 1. Value chain (Nestlé n. d.)

The company leader explains that the value chain provided above specifies the key stages of food production process in the organisation (Nestlé n. d.). More to the point, the process of food creation is coupled with the concepts of “innovation, creation and development” (Nestlé n. d., para. 2). As a result, the final product is characterised by a distinct set of unique gustatory characteristics and is destined to leave an impact on the consumer.

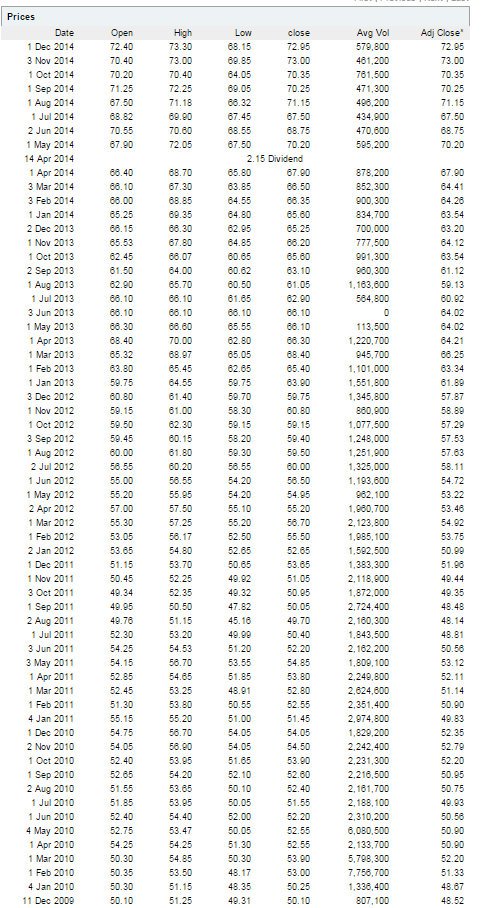

It should also be born in mind that the stock share price of the organisation has been remaining consistent throughout an impressive amount of time. Even the imminent crisis that followed the scandal related to the dubious ethics of the company and the use of improper components for children food did not make the situation as dreary as it might have been for any other organisation.

Indeed, one may notice that the stock shares price moved to 49.34 on October, 3, 2010 (‘NESTLE N’ 2014), yet the prices for the stock shares did not get any lower, which was quite an accomplishment for the organisation in the food industry.

Picture 2. Nestlé’s Stock Shares: Historical Prices (2009–2014) (‘NESTLE N’ 2014)

As the table above shows, except for the 2011 FDA related issue, the price for a Nestlé stock share has only been rising. It would be wrong to attribute this phenomenon to mere luck; Nestlé’s success was far from inadvertent. What seemed an accidental chance that the leader of the firm managed to use to his advantage turns out to be a well thought out plan and a result of the chemistry between the three key components of the company’s management.

Company’s Management Analysis

Though Paul Bulcke, the company’s CEO, is very reticent when it comes to determining the marketing strategies of the company, claiming that Nestlé’s marketing approach is based on the idea of segmentation almost entirely would not be a mistake. The company’s vision determines complete customer satisfaction and meeting the demands of every single buyer the firm’s main concern, which defines the methods of marketing extensively.

Largely presupposing that an in-depth analysis of the customers’ preferences and desires should be conducted on a regular basis (Vevey 2014), the above-mentioned approach has become the trademark asset of the company; however, in the modern environment of global economy, the company obviously finds it hard to split the target audience into groups that could share similar tastes in food.

The incorporation of the geographic principle of segmentation, however, prevents the exacerbation of the problem at the given point in time. Combined with the behavioural, demographical and psychological bases for segmentation, the aforementioned approach proves to be rather efficient even in the diversified realm of the global market (Hassan & Craft 2012, p. 346).

Research and Development Managing

The fact that Nestlé puts the stake on research and development shows clearly that the company is ready for entering the realm of the global market (Lasserre 2012). Reports show that the R&D department of Nestlé swarms with ideas concerning the improvements to be made to the company’s brand goods, as well as the creation of new brands (Fu et al, 2006).

The scale that the R&D department of Nestlé has gained is beyond impressive. Integrating the concept of information technology into its operations, the R&D department of the organisation has been the basis for Nestlé to grow and become more influential in the global market (Barnard et al. 2014).

The fact that the company was among the first organisations to introduce food science and technology into its R&D operations (Nestlé 2014) speaks for itself; Nestlé is clearly ready to come up with original inventions and experiment with flavours and ingredients for its products. However, corporate ethics has been left out of the organisation’s focus a few times, which nearly doomed the company (Boyd 2012).

Leadership Management

However, when it comes to choosing the feature that characterises Nestlé in the most positive light, one must recall its unique leadership strategy. The transformative leadership approach, which Bulcke prefers, proves rather efficient in terms of galvanising the staff members for efficient performance.

The official statement of the company’s employee relations policy incorporates the idea of togetherness and cooperation, therefore, making it clear that the leader and managers of Nestlé treasure relationships with their customers and co-workers the most: “Nestlé is committed to promoting a greater knowledge and understanding as well as an integral implementation of its Corporate Business Principles as the basis for being trusted by employees and stakeholders” (Nestlec, Ltd. 2010).

Management Issues Viewed from a Theoretical Perspective

The choices that Nestlé has made over the years of its development, especially the ones that relate to 2000s–2010s, may seem sporadic. A deeper insight onto the changes, which the Nestlé Company has undergone over the course of its existence, however, will show that the organisation leader has been quite consistent in his choice of the road that the organisation development should take. The further evaluation of the alterations, which Nestlé has suffered, as well as the principles which the firm is guided by, will shed some light on the specifics of Nestlé’s management specifics.

Emergent thinking as the key tool for Nestlé to evolve

When analyzing the concept that the company’s management is guided by, the theory of emergent thinking should be brought up. Defined as the aptitude to carry out the analysis of the existing assets and disadvantages and the following transfer from the process of understanding to actual action taking for addressing a specific issue (Torkar & McGregor 2012, p. 67), the theory in question allows one to get a deeper insight on the mechanism of Nestlé’s operations. In other words, Nestlé displays the ability of not merely evolving, but also to be conscious of the processes that it undergoes, as well as taking a firm grip over these processes, thus, making them controllable.

From differential to aggregation advantage

In its attempt to cater to the needs of much more diverse demographics, Nestlé has conjured a peculiar strategy based on aggregation as the key to shaping the firm’s value proposition. Though the company attempted at attracting customers from different tiers of society and different cultures in the past as well, this is an impressive foot forward for Nestlé, as it involves the transfer from a differential marketing strategy to an aggregation one.

Much to the credit of Bulcke, the company’s CEO does not pursue the goal of assimilation, allowing the company to retain its unique culture. However, the fact that the company is targeted at various cultures now is a sufficient proof for a major change.

Industry structure and government policy

Because of the need to transfer its production and organisation processes into the globalised environment, Nestlé has also experienced the necessity to shift from maintaining a strong industry structure to keeping an eye on the adherence to the government policies. In a retrospect, the progress that the company has made in terms of reconsidering its values and getting its priorities straight is truly fascinating.

It is hard to adapt towards the new requirements and, therefore, alter the traditional production process and marketing principle. However, Nestlé has handled the challenge that it was facing with impressive dignity and came up with a viable strategy for its further operations within the EU environment.

Particularly, the need to alter the retail system, as well as incorporate the principles of diversity into the corporate values of the firm and adopt the concept of shared value (Porter & Kramer 2011), deserves to be mentioned as the key steps towards entering the global market freely.

Resource disposal

The shift from the traditional to the globalised market environment has also heralded the era of a new approach towards resource disposal for Nestlé in accordance with the theory of emergent thinking. While previously preferring to state the possession of specific resources, Nestlé has shifted towards seeking new and more sustainable ways of resource disposal; the improvisation approach was the result (Campbell et al. 2011). Consequently, the company is fully capable of adopting a teleological approach towards the acquisition and the further use of resources

Network theory as a framework for evaluating Nestlé’s strategy

Seeing that Nestlé’s current strategy revolves around the usage of modern media as the tool for maintaining research and development processes at a decent level, it is pertinent to talk about the R&D approach from the perspective of the network theory. In accordance with the latter, the R&D department must be characterised by a well developed system of collaboration and are “represented by a network” (König, Liu & Zenou 2012).

It is only with the help of efficient cooperation with other departments and by feeling the pulse of the current R&D tendencies that an R&D department may succeed in designing the product that will become easily recognisable and popular among the target audience. Given the plenteous realm of the food industry, this is a very hard task, yet Nestlé manages to revive whenever its brand product becomes stale.

The company owes this aptitude of quick resurgence to its R&D strategy, which is obviously based on the tenets of the network theory. According to the official reports issued by the organisation, Nestlé has given its R&D centres the “global role” (Nestlé 2014, para. 9) in exploring new opportunities, particularly, the technological ones. With its zeal in providing “scientific expertise in plant science” (Nestlé 2014, para. 6), the organisation has found a way to vivify its R&D potential on a regular basis.

Key tool for keeping the sustainability rates intact

Thought the idea of synapse between the networking approach adopted by the company and the sustainability of Nestlé might seem somewhat farfetched, the connection established between the departments of the company, as well as between the organisation’s R&D departments all over the world, does affect the integrity of the corporate mechanism.

A closer look at the way, in which the company operates, will reveal the ambivalent nature of the phenomenon: by enhancing the networking system within which the members and partners of the company operate, Nestlé galvanises the process of information transfer. As a result, conclusions and necessary decisions are made faster, which reinforces the development of new brands and the search for new solutions (Fu et al. 2006).

Modern media at the service of the company

Seeing that the R&D process is related closely to the information management process, it will be reasonable to touch upon the latter, outlining the essential elements of the company’s approach. Despite the fact that the company is much more famous for using modern media for marketing purposes, the incorporation of networking tools into the company’s operations and the creation of a single network, within which the organisation operates, may also be viewed as one of the key achievements of the company.

The specified approach complies with the basic tenets of the networking theory, which claims that innovation and a business model (BM) of networking must go hand in hand: “The traditional brain-storm can used to find idea for creating BM that cater to new value forms, by supposing that the BM research process is infinite and creative” (Fu et al. 2006, p. 83). It is the possibility for an immediate and efficient exchange of ideas facilitated by the corporate network that allows for the R&D department to thrive and produce fruitful ideas on a regular basis.

Possible issues – technology inhibiting creativity

One must admit, though, that relying on the technological progress solely may inhibit the creativity of the employees, thus, turning the company stale. Therefore, one must bear in mind that the technological update of the corporation is only one of the essential steps to reaching excellence in information management.

On the one hand, the idea of technology being the block on the path of the employees exploring their creativity seems absurd, as technology provides the staff with additional opportunities in terms of information retrieval and the following processing. However, technology also seems to simplify the process of data management to the point where it acquires the air of everyday routine and a commonplace procedure, which it should not. Consequently, additional tools for spurring the staff’s creativity are desirable for Nestlé at present.

Path–goal theory of leadership and Nestlé

The particular characteristics of the Nestlé Company and the leadership approach that its CEO adopts is that it is very malleable, which is a positive characteristics for a company, yet an annoying puzzle for researchers. Indeed, it is very hard to identify the company leadership style with any of the existing ones, which also complicates the choice of a theoretical framework to view it from.

A range of researchers blame the organisation for its inconsistent leadership manner and dubious leadership ethics (Jallow 2009), specifically, the lack of control over its Chinese affiliates (Zutshi et al. 2009, p. 48). Official papers report the use of child labor in the specified region (Alvarez et al. 2010). However, the strategy in question seems to fit the tenets of the path–goal theory rather well.

Leader’s Behaviour

One of the key elements that determine the efficacy of the management principles utilised by Nestlé, leader’s behaviour described above is beyond reproach. As it has been stressed above, a new organisational dimension, strategic transformation and organisational transformation are the key characteristics of the leadership style of the company’s CEO.

These features correspond to the key tenets of the path–goal theory of leadership in general and its first stage, i.e., the design of a leadership behaviour that is directive, supportive, participative and achievement-oriented (Wafler & Swierczek 2013), in particular (McFerran et al. 2014, p. 469). By creating a new organisational dimension, Nestlé’s CEO creates the environment appropriate for the redesign of the stale corporate model adopted by most organisations and the introduction of achievement-oriented behaviour.

The fact that the new leadership approach allows for steering the company towards nutrition, health and wellness serves as the breeding ground for the provision of support and encouragement to the staff, as well as inviting every member to participate in the decision-making process (Mullins 2010).

Finally, the imperious yet emboldening manner of giving directions, which the organisation’s CEO manifests in his action plan and which the company’s managers mimic, fits the definition of directness as spelled out in the part–goal theory (Beek & Grachev 2010, p. 323).

Employees’ Motivation

It is essential that the approach adopted by Nestlé’s leader allows for motivating the staff fast and efficiently. Even the staff members that are prepossessed for a certain model of organisational behaviour are provided with an opportunity to mould different behavioural and attitudinal principles in order to be compatible with the company’s standards for performance and organisational values.

The way in which the company motivates its staff is nothing new, but its simplicity and solidness creates the environment for the company’s staff to thrive and evolve. Unexceptionable in terms of ethics and efficacy, the approach adopted by the organisation aligns with the key tenets of the part–goal theory in that it represents a well thought out process of turning the employees into devoted and responsible staff.

Implementing a transformative leadership strategy, the company’s managers set an example for the employees, which aligns with the stage of exposing the employees to proper leadership behaviour (Malik et al. 2014). As a result, the personal characteristics of the subordinates are taken into account, and they are assigned with the roles and tasks that they can handle.

The amount of trust, which the company’s managers put into the staff, serves as a powerful incentive for the staff to be perceptive and motivated according to the third stage of the part–goal theory. As a result, the staff accepts the assignments and responsibilities handed to them and experience job satisfaction feeling needed and important. Thus, Nestlé’s idea of putting people before systems proves quite efficient in accordance with the part–goal theory.

Goals and Their Attainability

From the tenets of the part goal theory Nestlé’s approach towards motivating the staff seems immaculate. Cavilling for the disadvantages of the chosen approach, though, one may assume that the specified leadership approach makes it difficult for the members of the company to attain the goals that have been set.

While the idea of “leading to win” (Nestlec, Ltd. 2014, p. 3), which Paul Bulcke, the company’s CEO, promotes, is quite reasonable, its vagueness might make the company’s leadership concept seem somewhat commonplace. As a result, the actual ways of meeting the objectives set in the course of compiling an action plan may become far too general to be implemented.

While this might be a minor nitpick, the specified characteristics of the company’s leadership approach is a reason for concern. It seems that Nestlé could benefit from following the part–goal theory closer and spelling its goals to the company staff in a more detailed manner.

Nestle Management Conclusion

Judging by the fact that the company has been maintaining sustainability within the organisational structure, production process and leadership domains, it can be assumed that Nestlé is on the right track. Therefore, unless the current leadership model, which leads to questioning the efficacy of defining the roles of responsibilities of each staff member, invite the threat of a possible misinterpretation of what the brand product must look like.

The company may have made several wrong steps in defining the patterns of organisational behaviour, et the overall assessment of the current state of affairs within the firm does not display anything egregious; quite on the contrary, Nestlé seems to have been thriving since the day that it was founded and has entered the environment of the global market dominated by the impact of information technology rather surely.

Indeed, it is obvious that Nestlé should align its current leadership strategy in accordance with the path–goal theory so that no misunderstanding should emerge in the process. In addition, the lack of emphasis on the culture in general and the diversification of the company in particular should be noted and addressed.

Recommendations

Apart from the need to take a better care of the organisation culture issues and rethinking the process of roles and responsibilities distribution among the staff members, Nestlé needs to improve its reputation by raising its quality standards and taking a better control over the production processes in its different affiliates.

Specifically, the child labor issue in China must be addressed immediately for the company to get rid of the stain blemishing its reputation. This presupposes that the leadership model should be altered slightly; luckily, the current leadership model is quite malleable and can be enhanced with the help of several more stringent control strategies.

Moreover, it is advisable that Nestlé should update its segmentation strategy in accordance with the demands of the target audience. Seeing that a range of parents are concerned with the accessibility of some of unhealthy Nestlé products to their children, the company should split its target customers into more specific age groups. Nevertheless, one must admit that the aforementioned considerations are mostly nitpicking.

Nestlé is a prime example of an organisation that has its processes under control and maintains a consistent sustainability rate. In a retrospect, one must admit that the company has made a gargantuan progress in terms of transferring from the product-based to the customer-based economy, integrating both traditional and new media in order to attract new audience. Deserving the success and attention that it receives, Nestlé is bound to remain in the top list of the most efficient organisations of the 21st century.

Reference List

Alvarez, G., Pilbeam, C. & Wilding, R. 2010, ‘Nestlé Nespresso AAA sustainable quality program: an investigation into the governance dynamics in a multi‐stakeholder supply chain network,’ Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 165–182.

Barnard, J. A., Wershil, B. & Balisteri, W. 2014, ‘Nestle nutrition young investigator research development award: NASPGHAN Foundation report on a 13-year partnership,’ Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 153–154.

Beek, M. v & Grachev, M. 2010, ‘Building strategic leadership competencies: the case of Unilever,’ International Journal of Leadership Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 317–332.

Boyd, C. 2012, ‘The nestle infant formula controversy and a strange web of subsequent business scandals,’ Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 283–293.

Campbell D., Edgar, D. & Stonehouse, G. 2011, Business strategy: an introduction, 3rd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK.

Coombs, W. T. & Holladay, S. 2011, ‘The paracrisis: the challenges created by publicly managing crisis prevention,’ Public Relations Review, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 408–415.

Doppelt, B. 2010, Leading change toward sustainability: a change-management guide for business, government and civil society, Greenleaf, Sheffield, UK.

Fu, R., Qui, L. & Quyang, L. 2006, ‘A networking-based view of business model innovation: theory and method,’ Communications of the IIMA, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 81–86.

Hales, C. 2001, Managing through organisation: the management process, forms of organization and the work of managers, 2nd ed., Thomson Learning, London, UK.

Hassan, S. S. & Craft, S. 2012, ‘Examining world market segmentation and brand positioning strategies,’ Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 344–356.

Jallow, K. 2009, ‘Nestlé as corporate citizen: a critique of its Commitment to Africa report,’ Social Responsibility Journal, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 512–524.

König, M. D., Liu, X. & Zenou, Y. 2012, ‘R&D Networks: Theory, empirics and policy implications,’ Discussion Paper, no. 13-027, 1–83.

Lasserre, P. 2012, Global strategic management, 3rd ed, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK.

Malik, S. H., Aziz, S. & Hassan, H. 2014, ‘Leadership behavior and acceptance of leaders by subordinates: application of path goal theory in telecom sector,’ International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 170–175.

McFerran, B., Acquino, K. & Tracy, J. L. 2014, ‘Evidence for two facets of pride in consumption: findings from luxury brands,’ Journal of Consumer Psychology, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 455–471.

Mullins, L. 2010, Management & organisational behaviour, 9th ed., Pearson Education, Harlow, UK.

Nestlé 2014, ‘Our global network,’ Nestlé. Web.

Nestlé, ‘Value chain,’ Nestlé. Web.

‘NESTLE N’ 2014, UK Finance. Web.

Nestlec, Ltd. 2010, ‘The Nestlé employee relations policy,’ ’ Policy Mandatory. Web.

Nestlec, Ltd. 2014, ‘The Nestlé management and leadership principles,’ Policy Mandatory. Web.

Porter, M. E. & Kramer, M. R. 2011, ‘Creating shared value,’ Harvard Business Review, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 1–13.

Rae, D. 2007, Entrepreneurship from opportunity to action, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK.

Ryland, P. 2013, ‘Reinventing Nestlé,’ Investors Chronicle, The Financial Times Limited, London, UK. ISSN: 02613115.

Torkar, G. & McGregor, S. L. T. 2012, ‘Reframing the conception of nature conservation management by transdisciplinary methodology: From stakeholders to stakesharers,’ Journal for Nature Conservation, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 65–71.

Vevey, V. 2014, Nestlé S. A., Switzerland, Geneva, Nestlé Company.

Wafler, B. H. & Swierczek, F. 2013, ‘Closing the distance: a grounded theory of adaptation,’ Journal of Asia Business Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 65–80.

Zutshi, A., Creed, A. & Sohal, A. 2009, ‘Child labour and supply chain: profitability or (mis)management,’ European Business Review, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 42–63.