World oil markets are currently undergoing a fundamental change, reminiscent of the break-up of the Standard Oil Trust in 1911 (Jain 1). Some argue that the petroleum industry is not only in a down cycle, but that it has been permanently changed.

The high volatility and competitiveness of this global market have encouraged the restructuring of the petroleum industry. Another factor that has contributed to the need for restructuring is that the oil market is now drastically reduced. There is a decline in some parts of the globe due to some factors not only in the downstream or upstream production, but there is also an increase in other regions. The decline is a contributing factor to this so-called restructuring (Jain 2).

Problem Statement & Description

Authors and risk management experts have indicated that the risk of investing in the oil and gas industry has increased dramatically. The evidence is clear and can be cited here:

- the Arab Spring and its effects, including terrorism and conflicts in Syria and Iraq, which show the risks associated with even seemingly stable governments,

- forced contract renegotiations and expropriations in the sector, including mining in various resource-rich countries (Venezuela, Argentina, and Russia) and

- recurring financial crises and the need for more regulation of financial organizations.

More generally, after a period of relatively low investment claim losses, there is a renewed awareness that investment risk, driven by political events, is still difficult to predict.

In the oil and gas sector, there are incidents of bargaining power over the life of a project between the country supplying the natural resource, the transit countries through which the export pipeline passes, and the multinational companies providing the financial capital and the technical expertise needed to develop and export the resource. Until exploration is completed and the field development facilities and pipeline infrastructure are built, superior bargaining power lies with the multinational companies, because the host government often does not have the financial, technical, and marketing resources needed to find and produce the oil and natural gas.

However, after the investment in the facilities and export infrastructure has been made by the foreign investors, the bargaining power shifts to the host government and the transit countries because they have the power to interrupt operations, pass legislation that impairs the value of the investment or in the worst case, expropriate the project assets (Wood 243).

Bilateral Treaties

Studies have shown that oil and gas contracts usually include a clause specifying the use of host country law in the resolution of disputes. Bilateral investment treaties also include a provision specifying the use of the law of the host state in international court proceedings and arbitration tribunals, but they also refer to other sources of law. Most bilateral treaties refer to four sources of law: (1) the bilateral investment agreement itself (the treaty); (2) the municipal (domestic law) of the host state; (3) the provisions of the contract relating to the investment between the parties; and (4) general principles of international law (Mucci 73).

Minimum Standard of Treatment

Minimum standards of treatment provide a treaty defined baseline or, in the words of one international investment tribunal “a floor below which treatment of foreign investors must not fall, even if a government was not acting in a discriminatory manner” (Newcombe and Paradell 233).

The range of economic interests that international investment agreements protect depends on the definition of “investment,” which most IIAs define broadly. Under customary international law, both tangible property (i.e. land, equipment, and inventory) and intangible property (i.e. company shares, dividends, bank accounts, contract rights, intellectual property, and goodwill) can be expropriated (Mucci 77).

Bilateral investment treaties typically contain a provision prohibiting either country from expropriating the investments of national of the other country without due process or just compensation or in violation of international law. The majority of expropriation cases in international law have involved deprivation of a foreign investor’s acquired rights and a corresponding acquisition, or appropriation, of those acquired rights by the state or a third party designated by the state (Mucci 77).

The international law presupposes a deprivation (expropriation) in the case of state interference in either the control of the land and other assets or the appropriation of financial benefits of owning property without changing its legal title (Mucci 77).

Most disagreements between the parties to a contract are resolved by the parties themselves, but when a disagreement cannot be resolved by the parties, the legal instrument most often referenced in the legal proceedings is the bilateral investment treatment between the country of the claimant and the country of the respondent.

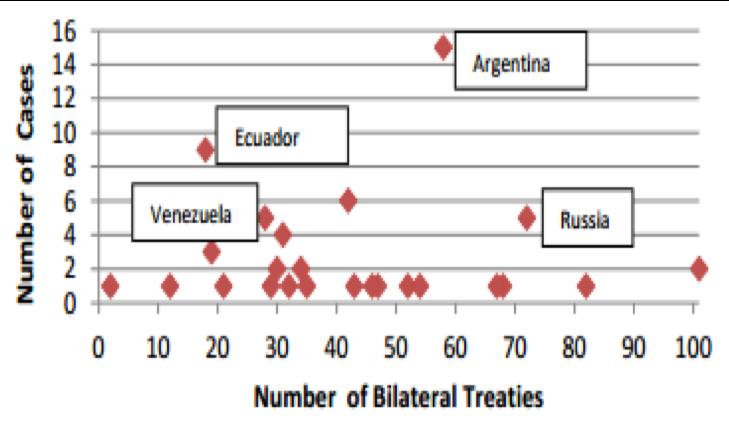

For example, Argentina has signed 58 bilateral investment treaties and had 15 cases brought against it by companies in the oil and gas industry. The Russian Federation has signed 72 bilateral investment treaties and had 5 cases brought against it. On the other hand, Ecuador has signed 18 bilateral investment treaties and had 9 cases brought against it; and Venezuela has signed 28 bilateral treaties and had 5 cases brought against it.

Also, 14 countries were involved in one case, yet the number of bilateral treaties a country has signed is not a reliable predictor of how many cases will be brought against it in an international court or tribunal (Mucci 80). An explanation is that, in a particular country, one regime may sign a large number of bilateral investment treaties to attract direct foreign investment and a subsequent regime may place more emphasis on wealth redistribution and resource nationalism. So that the large number of treaties a country has signed becomes an institutional artifact of the previous regime, but have no connection to the policy of the current regime. Figure 1 shows the number of bilateral treaties vs. Number of Cases (Mucci 81).

Oil consumption, Foreign Direct Investment, and Bilateral Investment Treaties

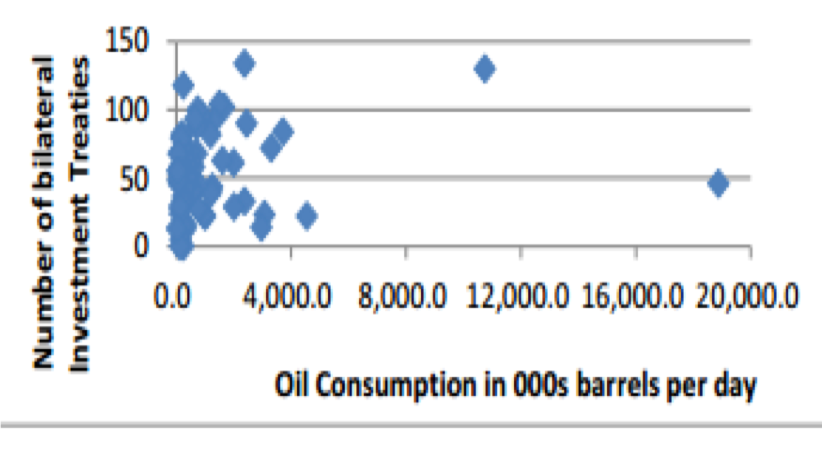

Does a relationship exist between the amount of oil a country consumes and the number of bilateral treaties it has signed?

According to studies, there is no observable relationship between the amount of oil a country consumes and the number of bilateral investment treaties it has signed. However, a statistical analysis of the data might show that a country’s oil consumption is statistically and substantively significant, even though it may be only one of several variables determining the number of bilateral treaties a country has signed. Figure 2 shows the number of bilateral investment treaties vs. oil consumption (Mucci 83).

Fairness and Effectiveness of International Courts and Tribunals

Given the general proposition that institutions develop and are sustained because they reduce risk and expand the range of economic possibilities, it is reasonable to think that international courts and tribunals are at least marginally effective, otherwise, there would be little reason for them to exist. The question is not whether they are effective, but how effective they are. Of the 68 oil and gas cases in the UNCTAD database, 16 have been resolved by a court or tribunal (8 were in favor of the plaintiff and 8 in favor of the defendant). These sixteen cases are not sufficient to conclude that international courts and tribunals are mostly impartial, but the fact that court or tribunal decided in favor of the plaintiff as often as they decided in favor of the defendant is encouraging (“United Nations Conference” par. 1-10).

Sources of Financing

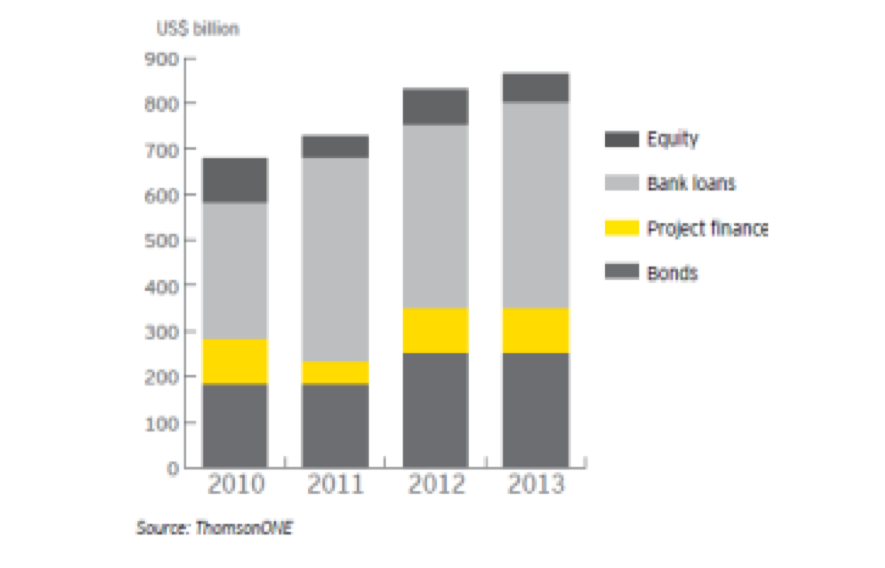

In 2013, capital expenditures and exploration expense (CAPEX) in the oil and gas industry were $682 billion and is expected to reach $723 billion in 2014 (Barclay’s par. 1). Figure 3 presents an estimate of the funds (financial capital), raised by oil and gas exploration companies and the source of those funds between 2010 and 2013 (Barclays par. 2).

Two observations are worth noting:

- the number of funds raised in 2013 was approximately $850 billion and the amount of CAPEX (not shown) was $682 billion in 2013. This implies that the industry raised capital in 2013 in anticipation of even higher capital expenditures in 2014;

- there is no explicit mention of internally generated cash flow from operations in this chart. Net cash flow from operations would, therefore, need to be added to these figures to estimate the total sources of financial capital (Paraskumar 3).

Equity Financing

Companies can acquire capital and investors can make equity in a company in two ways, publicly or privately. Public companies’ shares are traded on a stock exchange and can be purchased by anyone, at any time. The IOCs and many of the major NOCs are traded publicly, either in New York, London, Tokyo, or Hong Kong. Many of the medium-sized companies and even the “juniors” in the oil and gas industry are also publicly traded.

Common Stocks

A common stock gives its holders ownership in an oil and gas company that is proportional to the number of shares each common stockholder owns. Common stockholders also have a proportional claim on the net income of the firm after the obligations to all of the firm’s suppliers and creditors have been met. In this sense, the common stockholders bear the ultimate risk of failure or success of the enterprise. In the United States, the net income of the company is taxed at the company level, and any dividends that are paid to the stockholders are taxed again at the individual shareholder level.

Private Equity Investment

Investors can invest in a privately owned company only if the existing owners agree to expand the ownership of the firm. The potential investors must reach an agreement with the current owners regarding the amount of capital they will contribute and the proportional ownership the new investors will have in the expanded firm.

Private equity capital can come from individual private investors, institutional investors, mutual funds, and sovereign wealth funds. Private equity investors frequently hold the investment until it has attained significant value and then sell the company to another investor group or take it public in an initial public offering (IPO) (Paraskumar 3).

Hundreds of small oil and gas firms rely on private equity capital to fund their operations. These firms often have significant potential but have limited access to other forms of capital because they have little operating cash flow and few assets, in the beginning, to present to a commercial bank as collateral for a loan. And although advances in technology have improved the odds of finding oil and gas, success is still elusive; three-quarters of all exploration wells are “dry holes,” either because there is no oil there or because geologists have been unable to accurately identify the location of the oil or natural gas.

However, ninety percent of the petroleum produced in North America is produced by independent producers, not IOCs. Many of them are private companies that rely on private equity investment to finance their operations.156 Private equity groups made significant investments in the oil and gas industry in 2012 (1,590 private-equity-backed deals valued at $152.3 billion) (Rosa par. 1).

Debt Financing

Debt financing is available in two forms, commercial bank loans and the issuance of bonds. The most common form of oil and gas financing is senior debt obtained from a bank or a syndicate of banks, (see Figure 7 above) through a revolving credit facility or a term loan credit facility. (A revolving credit facility is a line of credit for which the customer pays a commitment fee and is then allowed to borrow money from the lender up to the agreed limit.

It is usually used to fund ongoing operations and the amount of the borrowing changes each month depending on the customer’s current cash flow needs). If the loan is made to provide an oil and gas producer with working capital or funds to develop existing oil and gas properties, a revolving credit facility is used. However, if the loan is made to purchase oil and gas properties, a term loan facility is typically used.

Banks usually secure the loans with a mortgage or deed of trust on the oil and gas properties that are being acquired or developed using the proceeds of the loan. These mortgages or deeds of the trust permit the bank to foreclose on the oil and gas properties in the event of a default by the borrower under the credit agreement. If it becomes necessary for the bank to foreclose on the borrower, the bank can sell the oil and gas properties and recover part of the funds it loaned (Muñoz 223).

Most small and medium-sized firms in the oil and gas industry rely on commercial banks for short-term and medium-term loans to finance their operations, but the availability of long-term commercial bank loans and access to the bond market has historically been limited if these firms specialize exclusively in the exploration and production segment of the industry. In that case, these firms must rely on public and private equity for capital.

In contrast, the super-majors (Chevron, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, BP, and Royal Dutch Shell) and other IOCs have continuous access to commercial bank loans and the bond market, because of their vertical integration; more diverse lines of business; diversity of their exploration and production projects; the long history of operation; and their overall size.

Check Sheet

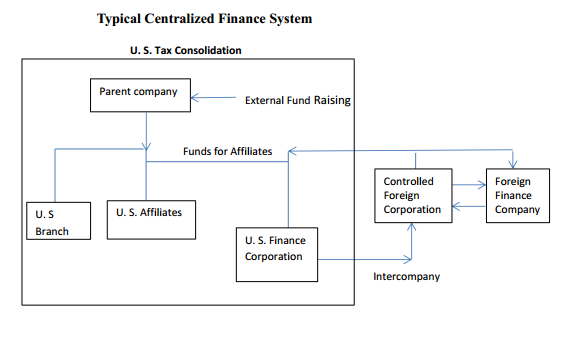

Figure 4 shows the centralization of the financial system in the U.S. (Razawi 102).

Recommendation and Conclusion

Managing Financial Risks

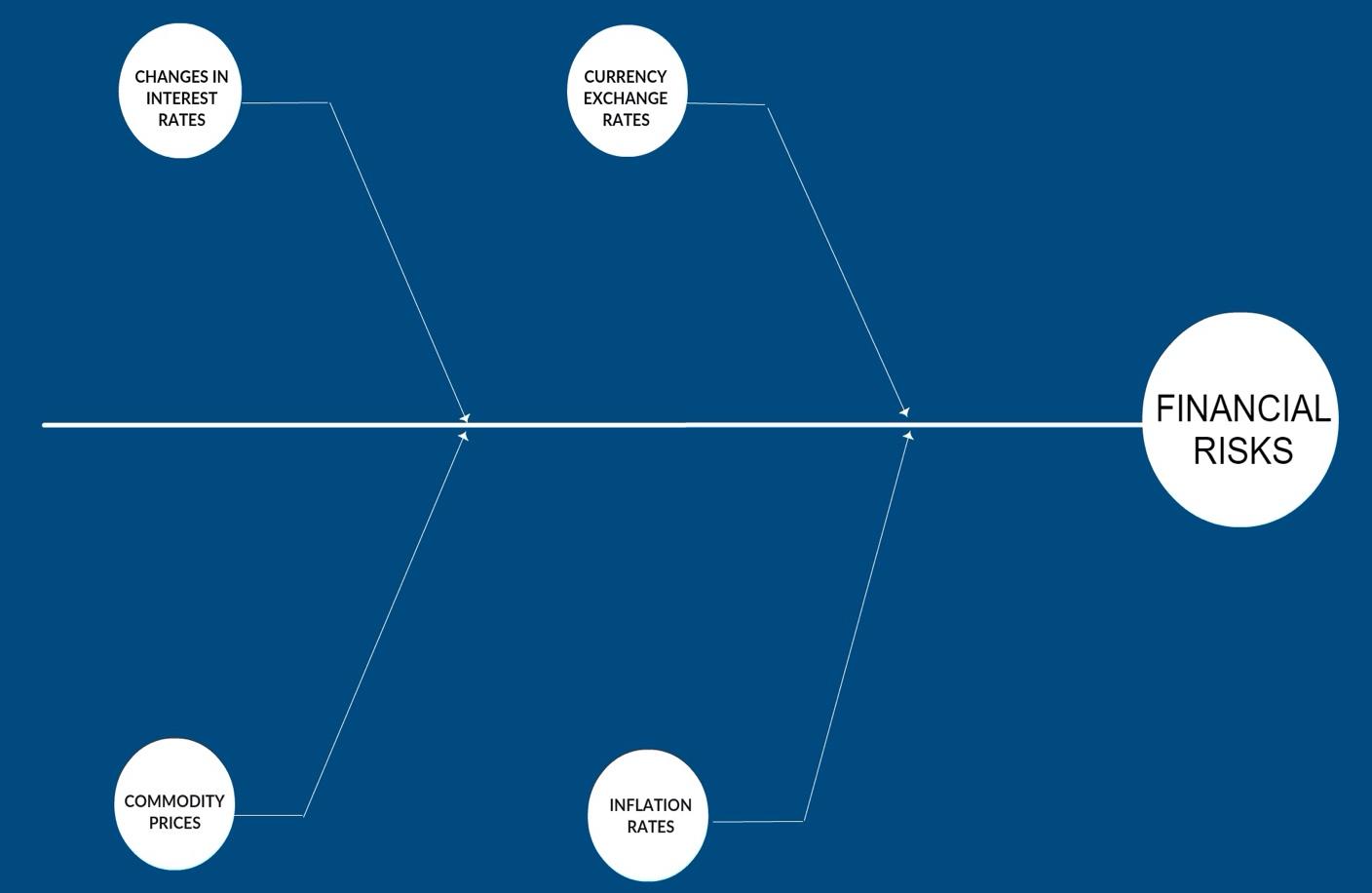

Financial risks include

- changes in interest rates;

- currency exchange rates;

- commodity prices; and

- inflation rates.

Financial risks can be managed through a combination of derivatives and long-term purchase agreements. Derivatives include commodity futures, forward contracts, options, and swaps. Long term purchase agreements are usually negotiated before the development of an oil or gas field to secure a market for the future output from the field. Figure 5 shows the fishbone diagram of financial risks

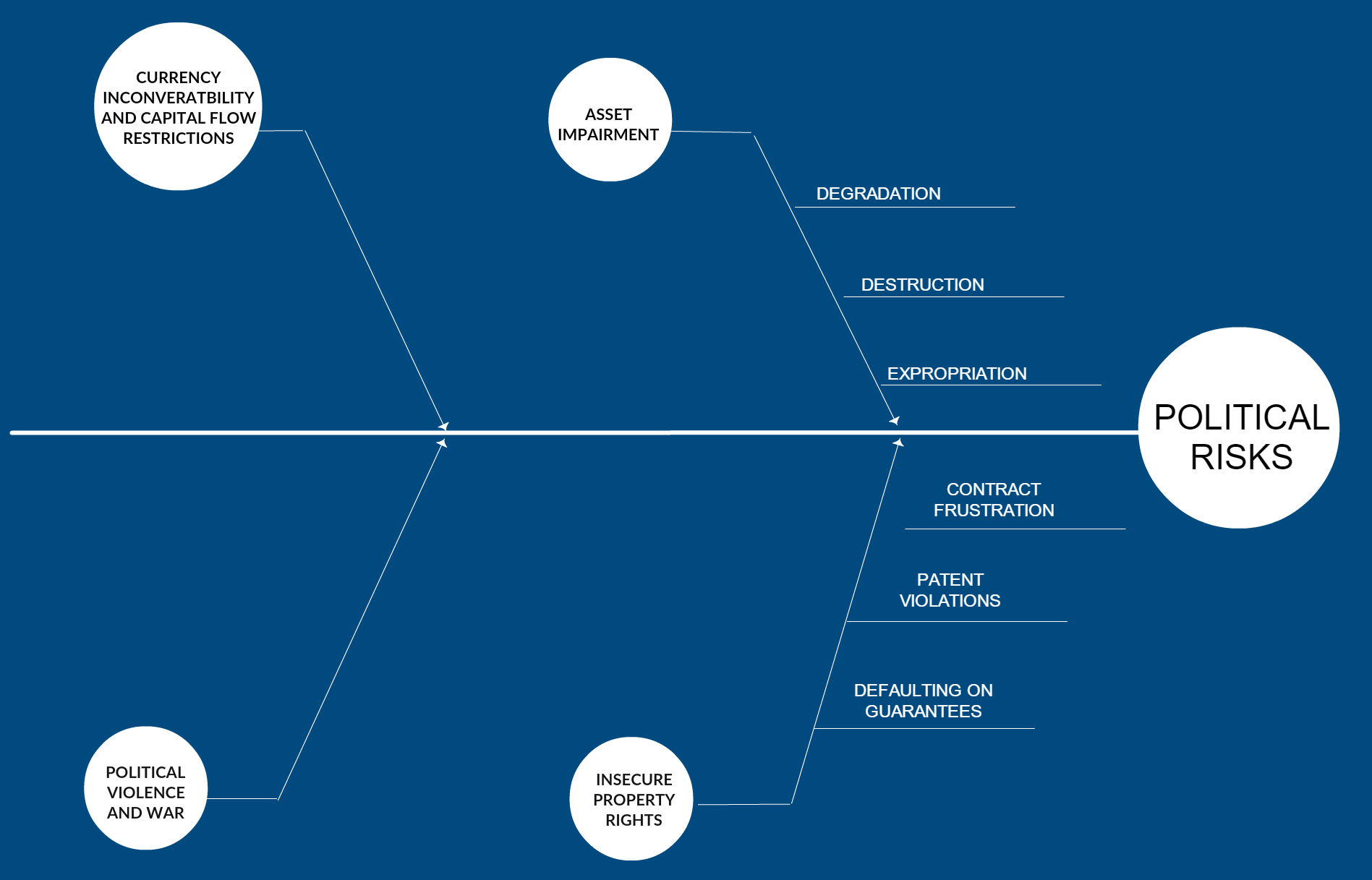

Managing Political Risks

Political risks include

- asset impairment (degradation, destruction, and expropriation);

- currency inconvertibility and capital flow restrictions;

- political violence and war; and

- insecure property rights (contract frustration or abrogation, patent violations, host country failure to honor guarantees and changes in host country laws) (Popovic and Lathrop par. 1-5).

Political risks cannot be easily managed; therefore, before the investment in a foreign country, it is necessary to assess the degree to which it is exposed to political risks by assessing “the stability of politics and attitude towards foreign investment” (Hou 28).

Moreover, the investor should assess the current economic condition of the foreign country to better understand how it might change in the future. To this end, it is necessary to evaluate the country’s GDP, inflation, unemployment rate, and consumer price index (CPI), and the structure of its financial markets (Hou 28). Rating agencies like Moody and S&P could also provide information about the political climate of the country of interest. Other instruments of hedging political risks are political risk insurance, joint business ventures, lobbying, and prominent alliances and community initiatives among others. It will help to minimize the political risks associated with foreign investment. Figure 6 shows the fishbone diagram of political risks.

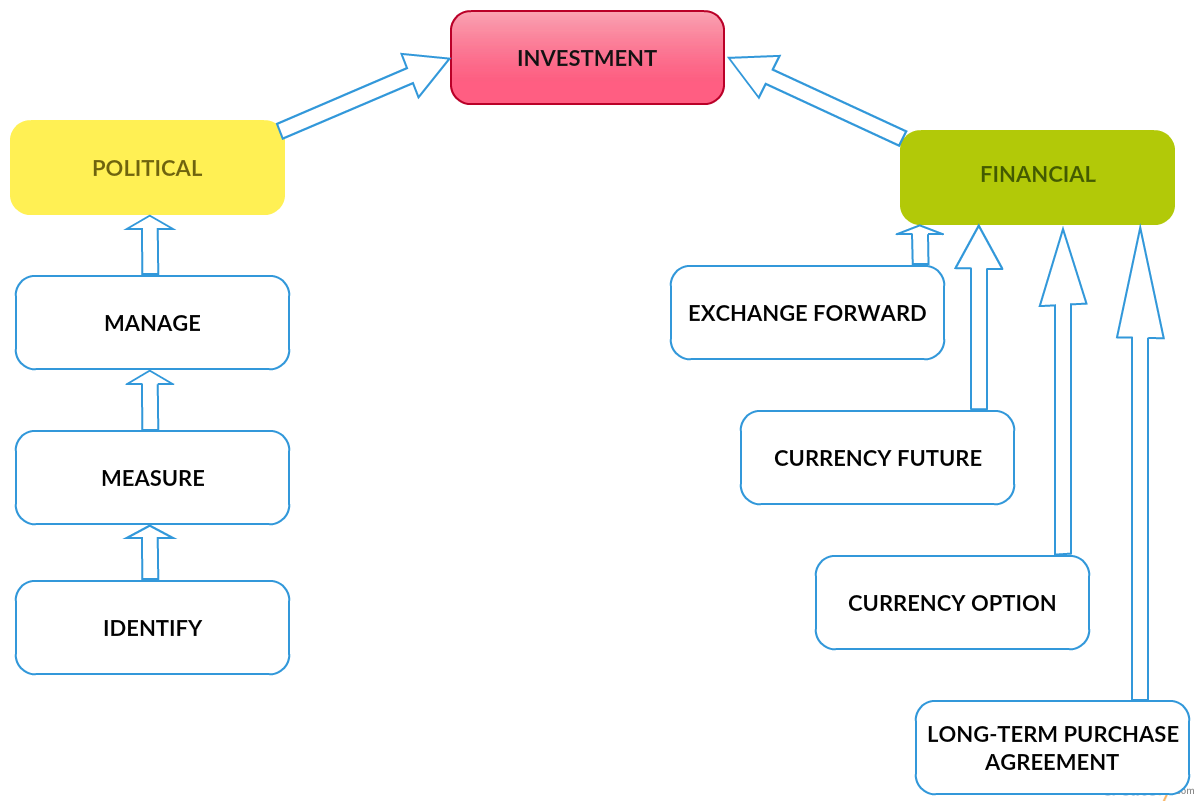

Figure 7 illustrates the process of identifying and managing political and financial risks before investing in a foreign country.

Figure 8 shows a Pareto diagram of the most important foreign investment risks.

Taking into consideration the fact that host countries often have bargaining power over the project after it is completed and the field development facilities and pipeline infrastructures are put in place, it is necessary to minimize political and financial risks before the initiation of the project. To this end, it is necessary to utilize financial hedging instruments and political risk control methods described above. It will help to substantially improve the quality and efficiency of the company’s services.

Works Cited

Barclays. “Global 2014 E&P Spending Outlook.” PennEnergy. Web.

Hou, Xuemei. “Risk Management in International Business.” Risk Management, vol. 14, no. 1, 2013, pp. 21-29.

Mucci, Steven, “Managing Political and Investment Risk in the International Oil and Gas Industry” (Ph.D. thesis, The University of Missouri, 2015), 1-23.

Muñoz, Jeffrey. “Financing of Oil and Gas Transactions.” Texas Journal of Oil, Gas and Energy Law, vol. 4, no. 2, 2009, pp. 223-267.

Newcombe, Andrew, and Liuis Paradell. Law and Practice of Investment Treaties: Standards of Treatment. Kluwer Law International, 2009.

Paraskumar, Jain, “Evaluating the Impact of Sustainability and Pipeline Quality on Global Crude Oil Supply Chain” (Ph.D. thesis, The University of Texas, 2015), 1-19.

Popovic, Neil, and Alex Lathrop. “Recovery Tactics Outlined for Foreign Takeover Losses.” OGJ. Web.

Razawi, Hossein. “Financing Energy Projects in Developing Countries.” The Global Oil and Gas Industry – Management, Strategy and Finance, edited by Andrew Inkpen, and Michael H. Moffett, Pennwell Corporation, 2011, pp. 100-111.

Rosa, Taina. “Still Not Buying into a Buyout Boom.“ Pipeline. Web.

“United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.” Iiadbcases. Web.

Wood, David. “Chapter 10: Petroleum Economics, Risk and Opportunity Analysis.” Energy, Finance and Economics – Analysis and Valuation, Risk Management, and the Future of Energy, edited by Betty J. Simkins, and Russell E. Simkins, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013, pp. 243-251.