The principles of democracy and equality have been established in the world only recently, in the 20th century. It is important to say that before that period, terror and barbarism were governing the world; however, such issues as slavery and colonialism used to be the reality of developed countries in spite of the unnatural essence thereof.

The 19th and 20th centuries, though demarcating the beginning of a modern, civilized era (especially in the advanced and developed Western Europe), still manifested the largest-scale expansionist endeavors of the West towards the Middle East and North Africa. France and the British Empire were distinguished colonizers at that time, and the relationships of these countries with their colonies were specifically distinct from international relations existing in the rest of the world.

The power of colonizers was so strong that the Western countries, by means of exploring, researching, and documenting their findings about the East, have managed to create an artificial, stereotyped system of concepts regarding the East – Orientalism. It appeared in the 19th century as a separate scholarly study dedicated to Orient; scholars researched people living there, their traditions and customs, their dressing, their language, personal and family relationships, etc.

As a result, Orientalism grew to represent the Orient as seen by Westerners; nevertheless, it did not render the Eastern reality, since it did not correspond to the realistic Eastern context, and manifested only the prism of Western perception.

As a result of these processes, an assumption about the tendency of Western artists to create political propaganda supporting violent occupation and subjugation of inferior cultures by the West appeared.

There is a common opinion that the majority of Orientalist works in the 19th and 20th century were initially made with the intent to promote colonialism and superiority of Westerners over Easterners. Since there is a conflicting body of knowledge and evidence on this point, the issue needs further analysis in support for it, or in opposition to it.

The starting point in the analysis of Orientalism has traditionally been the reference to the work of Edward Said, Orientalism. This book has become a turning point in the assessment of Orientalism, since before this publication it had been considered a positive phenomenon in the history of East-West relationships.

It was Said (1978) who revealed the true nature of Orientalism as an invented, made-up term, system of concepts, scheme of dominance, that allowed Westerners to explore the East without even being there. As the author noted at the beginning of his book, Orient is not analogous to the East, as Orient is a purely Western invention symbolizing romance, exotic beings and dressing, memorable and original experiences, etc. (Said 1978, p. 1).

Indeed, Orientalism has been created to become the Western style of dominating, remaking, and exercising authority over the Orient by Western colonizers (Said 1978, p. 3).

Attention towards Orientalism has renewed nowadays, since there is much Orientalist propaganda and reinforcement of old stereotypes visible in the new media.

Modern films and TV shows, magazines and travel guides try to romanticize the East again, misleading the Westerners and precluding them from an objective assessment of the Eastern reality, especially taking into account the fact that some colonies still exist. Therefore, one has to understand the nature of the impact that the notion of Orientalism brings to people concerned with it.

It is easier to explore the impact of Orientalism on human perception of the East through the works of art produced in the 19th and 20th centuries, since they reflect the vision that critical thinkers and creative personalities (the forefront of the human thought) had about the East through the prism of Orientalism.

It is quite possible to assess the propaganda essence of Orientalism in literary works, but the purpose of this paper is to focus on the works of art reflecting the main points of this trend. As Nochlin (1989) noted, the flourishing Orientalist painting was closely associated with the successful Western expansion to the East at the verge of the 18th and 19th centuries (p. 33).

However, the main goal of Orientalism in painting is regarded to be the documentary realism, i.e., the urge of artists to document the unseen, unusual, and exotic they came across in the East, and to show these unusual images to the rest of the European world (Nochlin 1989, p. 33).

Accessing the issue from a purely artistic viewpoint, one can state that there is no place for propaganda in art; however, the opposite has been proven by many centuries of human experience. Notwithstanding the active role of art in assistance for the ruling regime, there is still a common argument about the distance that art keeps from politics.

As MacKenzie (1995) noted in his analysis of Said’s work, genuine arts and political ideologies have always tended to operate in counterpart, and not in alignment (p. 14). Therefore, one can assume that true artworks reflected human feelings and impressions about Orient, and not the programmed, propaganda messages for the Western world.

Obviously, there was a certain place for propaganda in the Orientalist art, though the portion of propaganda in visual arts was incomparably lower than that in literary works. As Meagher (2004) noted in her analysis of the 19th-century Orientalist art, some strong propaganda features in art may be tracked in the works of Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835) and Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825).

These artists made a great effort in proliferating Napoleonian imperialism, and painted several artworks presenting Napoleon Bonaparte as a healing power, a godlike personality for the world of chaos, barbarism, and lawlessness of the East (Meagher 2004, para. 2).

Some of the propagandist works of these authors are Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804, Louvre) and The Coronation of Napoleon in Notre Dame (1806). These painters obviously had their personal benefits from the propagandist activities, since they were close to the Emperor Napoleon in France.

Another format of propaganda produced in Orientalist art is in the depiction of Oriental people as uneducated, wild, and fierce. These themes dominated in the paintings of Eugene Delacroix (1798 – 1835) who also represented a propagator of colonialism and never revealed the true nature of the East, but not Orient, though he has been fascinated by Oriental themes during his whole life (Meagher 2004; para. 2; Bernard 1971, p. 123).

The focus on Oriental cruelty and violence was partly presupposed by Delacroix’s interest in the Greek-Turkish war unleashed right at the beginning of the 19th century. However, there were images he created that deeply impressed the public in the civilized West in a negative way, for example, Massacre at Chios (1824) and Death of Sardanapalus (1827-28)

In his painting Massacre at Chios, Delacroix represented an awful, dramatic image of the Chios massacre only according to his own perception, without seeing Oriental people at all.

The painting was accomplished only due to the help of Delacroix’s friend, Monsieur Auguste, who was a fascinated Orientalist in Paris, and who granted clothes and objects to paint (Thornton 2009, p. 67). It appears hence quite illogical to suppose that Delacroix had the least adequate idea of the Oriental world he depicted, and his portrayal can hardly be called realistic or neutral in terms of propaganda.

The second violent painting for which the propagandist spirit of Delacroix’s paintings is recognized is the Death of Sardanapalus – it was not recognized by the civilized Western society for the cruelty and violence exceeding all limits in the depicted scene. Delacroix obviously perceived Oriental people as cruel barbarians living according to the principles of force and intimidation.

He was able to go on a short trip to Morocco and Algiers in 1884 (Orientalist Art of the Nineteenth Century, n.d., p. 1). Though Delacroix managed to make many sketches during that trip, and his impressions about the Eastern world were reaffirmed, Delacroix’s paintings, especially the later ones, were far from the Oriental reality (Thornton 2009, p. 69). Thus, there is no surprise in the focus on the healing power of Westerners saving the Orient from its own self-destructiveness evident in the works of many painters of that time.

Notwithstanding the fact that Orientalism is a propagated and stereotyped concept in itself, and it was artificially created for the enhancement of dominance of westerners over the colonized East (MacKenzie 1995, p. 4), there were still genuine fans of Orientalism with sincere urge to understand Eastern people and to become closer to them. One of such lifelong fans of Orient was Etienne Dinet (1861-1929).

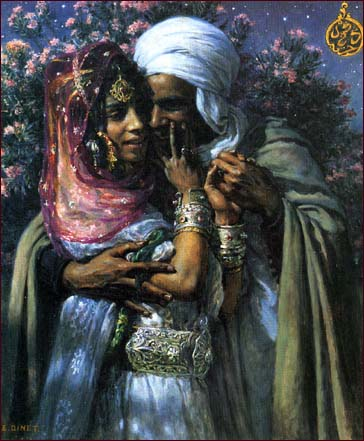

This French painter dedicated nearly 50 years of his life to the travels between France and Algeria after only one trip there. Dinet depicted Eastern people as beautiful, cheerful personalities possessing their individual wishes, urges, dreams, and opinions. The most famous works of Dinet are Abd el Gheram and Nour el Ain, Slave of Love and Light of my Eyes (1904) and Girls dancing and singing (1902).

The painting Slave of Love and Light of my Eyes (1904) shows the couple in love; the lovers have to conceal their feelings and can meet only at night to enjoy their love and to say a few tender words to each other. The painting is so lively and positive that one can hardly see any stereotyping or propaganda in it; it is full of love, life, and ability to be happy. Therefore, the present picture is a memorable example of pure Orientalism without any political messages or intents.

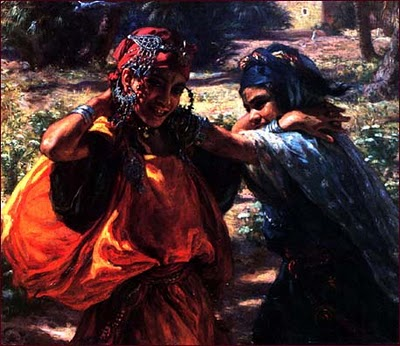

Another painting of Dinet appreciated by the majority of art experts and nonprofessional fans is the depiction of two girls from the Ouled Nail tribe. Dinet dedicated many years of his life to approach the people of the tribe closer, and to acquire the ability to depict them with respect and understanding (Orientalist Art of the Nineteenth Century n.d., p. 1).

Comparing the experience of Delacroix to visit a Moroccan harem (Neret 2000, p. 54) with the lifelong effort of Dinet to get closer to the understanding of Easterners, one can assume that the realistic rendition of the genuine Orient was possible only in Dinet’s works.

Dinet had a mediator between him as a Westerner, and the Eastern world in the face of his lifelong friend Sliman ben Ibrahim (Thornton 2009, p. 77). They realistic perception of the East by Dinet is also felt in his disappointed remarks about Egyptian context, in contrast to the majority of Orientalists who took their inspiration and themes from Egyptian images (Thornton 2009, p. 77).

Concluding the present analysis of propaganda in the Orientalist art, one has to infer that visual art as such did not reflect the propagandist urges. Obviously, there were many inconsistencies in the artwork and reality of Eastern life and culture, mainly due to ungrounded information and lack of hands-on experience.

The majority of Oriental paintings revealed the Western fascination with the exotic and the unknown; Westerners were attracted by the vivid colors of clothes and surroundings, the unusual design of dressing, furniture, and houses.

The lifestyle and national character of Oriental people also produced much interest; harems, aggressiveness and violence in war conflicts, etc., could be left out by the civilized Western world. Surely, the Orient was perceived as a subordinate territory, and people felt its established inferiority, but this awareness seems to have been created by a much larger discourse than Orientalism art.

References

Bernard, C 1971, ‘Some Aspects of Delacroix’s Orientalism’, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 123-127.

MacKenzie, JM 1995, Orientalism: history, theory, and the arts. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Meagher, J 2004, “Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Web.

Neret, G 2000, Eugene Delacroix, 1798-1863: the prince of romanticism. Koln, Germany: Taschen.

Nochlin, L 1989, “The Imaginary Orient” in The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society, New York, NY: Harper and Row, pp. 33 – 57.

Orientalist Art of the Nineteenth Century: European Painters in the Middle East n.d. Web.

Said, E 1978, “Introduction” in Orientalism, New York, NY: Vintage Books, pp. 1 – 28.

Thornton, L 2009, The Orientalists: Painter-Travelers. Paris, France: ACR PocheCouleur.