Re-orientation

Addressing the reading issues that low ability students face in an English class is an essential step towards increasing the academic potential of these students.

In order to study the ways for improving the students’ progress, it is appropriate to propose the intervention based on implementation of the peer assessment into a teaching strategy. The class selected for the intervention includes a group of thirteen year seven low-ability students.

It should be noted that the whole class consists of twenty students.

Among the specified group of students, two students face problems communicating English as they are ESL students (English as a Second Language); 12 students are with special educational needs (SEN); additionally, one student out of five in the group has either dyslexia or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Their knowledge of grammar and syntax rules is of concern and requires attention and improvement (previous results ranged from 3c to 4a; however, the KS2 results showed a tendency of 4a to 5a).

Though, compared to the initial test results, the final ones can be discussed as a minor improvement, the current evidence points to the need for the students to work on new skills acquisition and memorising skills development.

The literature review provides opportunities to define methods for addressing the needs of the students in question. In their research, Falchikov and Goldfinch (2000) note that students usually lack understanding of the role of peer assessment as well as the significance of providing accurate evaluations of their peers.

Zingaro (2013) also focuses on the role of peers in conducting assessments. These discussions support the necessity to provide students with a detailed explanation on the process of evaluation of their peers’ success as well as with a close supervision of the specified procedure.

Moreover, it has also been noted by Cox and Maher (2007) that peers usually need to provide each other with positive reinforcement so that they could feel motivated to achieve better results.

Focusing on low achieving students’ needs, it is also relevant to refer to Carter (2014) who states that these students need graphic data in order to understand the mechanics of the learning process better.

It is also suggested by Murayama, Perkin, and Lichtenfeld (2012) that the incorporation of an element of a game into the learning process is helpful to address the specified issue in the learning process, and the introduction of differentiated assignments allowing the choice of interesting tasks proposed by Burguillo (2010) can also enhance the learning process among low-ability students.

The review of these sources has resulted in designing the intervention oriented to low-ability students and their peers with high scores responsible for providing assessment. Moreover, an overview of the existing literature has shown that students need positive reinforcement from their instructor in order to succeed during the intervention.

Thus, the study by Falchikov and Goldfinch (2000) shows that it is the teacher’s responsibility to guarantee a positive outcome of the peer assessment. The findings are important support the design and implementation of the effective intervention.

Intervention

The intervention lasted two weeks, including the observation of students during ten days. In the course of the intervention, lessons in English were conducted, and the students were asked to assess each other’s reading skills with the focus on peer assessment.

The first lesson started with the introduction of the students to the idea of peer assessment, and detailed instructions were provided. The students were given a set of statements for the evaluation of their peers, while the teacher explained what each part of the assessment addressed.

The teacher suggested that the students should read the questions out loud and ask if anything was not clear. As soon as every student understood the purpose of the questions, they were divided into pairs; then, the reading of the first excerpt from the book for Reading in English started.

After the reading, the students were asked to evaluate their peer’s reading skills according to the previously mentioned criteria and instructions and write down the results.

Students answered the questions concerning the contents of the excerpt and the new vocabulary; evaluated their peers’ responses assessing the accuracy of the vocabulary use and correctness of the factual information. During two weeks of the intervention, lessons ended with a game or other appropriate activities.

One game was based on locating words in a grid filled with letters and defining these words. The students then evaluated their peers’ skills based on the amount of words found and the time taken to locate the words (the students were given fifteen minutes, a minute per word).

The basing on the findings of Knight et al. (2014), the teacher scaffolded the students throughout the assessment helping them measure their peers’ success to help the students to feel more confident.

The specified model was repeated throughout the conducted lessons in reading with slight alterations because the game could be replaced with a similar crossword activity.

At the end of Week 1, students were asked to answer open questions from the questionnaire. Thus, students were asked to answer Questions 5, 7, 8 (Appendix A). The procedure was repeated at the end of Week 2 in order to ensure comparing the answers with the help of the qualitative data analysis.

Being asked to answer questions, low ability students displayed keen interest and genuine excitement about the activities only during the second week because they hesitated to grade each other during the first week of the intervention.

However, as soon as the teacher assured them that the grading by peers would not affect their actual score calculated by the teacher, they became rather enthusiastic about the process and reflected these emotions in their answers.

Still, high achieving peers seemed to be quite bored after they realised that the pace of the lesson was not going to be accelerated during Week 1 and Week 2, and they informed the teacher about that fact.

According to Wadesango & Bayaga (2013), the fact that motivation can drop among high ability students in the process of the intervention points at the necessity to introduce the set of activities that would keep the attention of high achieving students and at the same time be approachable for low ability students.

As a result, the games to conclude lessons were changed to address the needs of high-ability students. The use of a game as a type of activities that both low and high ability students may participate in seemed to have worked quite well within the specified setting.

Following Dominiquez et al. (2013) and Connolly et al. (2012), the success of the strategy can be explained by the fact that games presuppose the incorporation of a competition factor and, thus, make the learning process more engaging for high achievers.

Question 6 from the delivered questionnaire was answered by the students at the end of Week 1 in order to state the motivating factors for low achievers to adapt to the peer assessment (Appendix A).

These students seemed to lack confidence when carrying out their first evaluation of their peers, and were more lenient to each other than the standards required. As a result, the students who were obviously scoring lower than the rest of the class did not feel willing to make greater efforts.

As a result, the focus on helpful tips for students was important for the further analysis of the data.

At the end of the second week of intervention, the students were asked to answer Questions 1, 2, 3, and 4 from the questionnaire in order to demonstrate their attitude toward the peer assessment and conclude about improvements and motivation (Appendix A).

During all ten days of the intervention, the observation was conducted, and the results were fixed with the help of the Observational Checklist (Appendix B). It was important to discover any changes in the activity of low achieving and high achieving students associated with the use of peer assessment at lessons.

Changes in activities were noted for the further analysis. It was noticed that low ability students and high ability students demonstrated different levels of involvement during Week 1 and Week 2, and the further observation was important to explain these notes.

According to Lavy, Paserman, and Schlosser (2011), in order to develop new skills and not only retrieve but also process and remember new information, low ability students have to engage into the meta-cognition process.

In other words, the students must understand how they acquire new skills and information, as well as use this knowledge for their further studying process. Peer reviewing, in its turn, allows students to understand how they perceive the world around them.

In this context, the observation was necessary to understand how cooperation and interaction with peers could influence the collected results (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2011a; Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2011b).

Data Analysis

The qualitative data aim to represent changes in the students’ perception of peer assessment, whereas the quantitative data aim to demonstrate the changes in the low-ability students’ progress in numerical terms.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Questions 5, 7, and 8 provided in the used questionnaire are open, and the students were asked to describe their thoughts on the experienced peer assessment in their own words.

Students answered these questions after the first week of intervention and after the second week. Table 1 represents meaningful details taken from the students’ answers typical for Week 1 and Week 2 as well as identified themes and emotions.

Table 1. Details Taken from Students’ Responses, Themes, and Emotional Colouring

Table 1 indicates the coded responses of the students on the purpose of the peer assessment and their overall perception of the task. The responses are coded in relation to the emotions and attitudes experienced by students during the two weeks of intervention and presented in Table 1 as “Themes”.

The generalised discussion of identified emotions is presented in the table in the column titled “Emotional Colouring” in order to ensure comparing of the students’ emotions, attitudes, and motivation typical for Week 1 and Week 2.

According to Table 1, about 75% of students experienced such negatively coloured emotions as uncertainty, fear, and confusion associated with peer assessment during Week 1. Only 35% of students could restate the purpose for peer assessment told by the teacher in instructions.

The table also shows that during Week 2, 80% of students formulated the purpose easily and demonstrated such positive emotions as enthusiasm and pride. 15% of students felt bored because of the task’s simplicity.

According to Acosta and Ward (2010), emotional colouring is important to be checked by instructors in order to determine the emotions that students feel when participating in the class activities.

Adopted in the qualitative data analysis, the focus on emotional colouring helps to analyse the students’ answers in terms of their attitudes and emotions. During Week 1, the students were rather reluctant to accept the new approach in learning.

The situation differed during Week 2. Thus, following Bryman (2008), the emotional reaction of the students towards peer assessment, as well as the final testing process, can be divided into two major groups, positive and negative emotions.

According to Jordan et al. (2013), negative emotions such as fear of making mistakes, lack of initiative and engagement in learning, confusion, and unwillingness are associated with high ability students’ adaptation to the new task.

Positive emotions like curiosity, enthusiasm, and pride typical for Week 2, represents students’ achievements in relation to skills acquisition and responsiveness to the teacher’s instructions (Jordan et al. 2013).

Quantitative Data Analysis

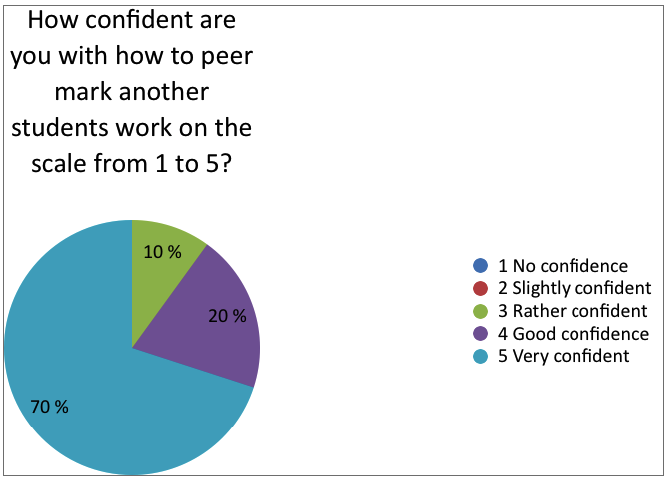

Questions 1 and 2 presented in the questionnaire are related to each other, and the main focus is on Question 2 asking about students’ confidence regarding peer assessment and marking the other students’ work.

At the end of Week 2, all students reported that they know how to conduct the peer assessment, and Figure 1 provides the visual representation of the percentage of students feeling confident or non-confident while marking the work of their peers.

Differences in the level of their confidence were assessed with the help of the 5-point Likert scale measuring confidence from 1 – “No confidence” to 5 – “Very confident”.

Figure 1. Students’ confidence on how to peer mark another student’s work (%)

Figure 1 demonstrates that 70% of students described their attitude as “Very confident”, 20% of students assessed the level of confidence as good, and 10% of students noted that they were rather confident in terms of peer marking the other students’ work.

The results demonstrate that there were no students indicating low levels of confidence in procedure.

Denton at al. (2013) note that students are inclined to demonstrate high levels of confidence in peer assessment after a period of practice, when fears are changed with first successes. Therefore, at the end of Week 2, students can reasonably discuss themselves as confident in marking each other’s work.

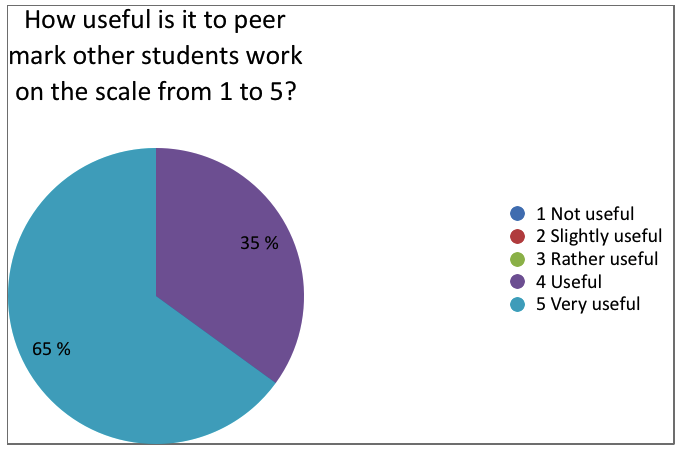

Question 3 asks students about the overall usefulness of using peer marking or peer assessment.

Figure 2 demonstrates the percentage of students discussing peer marking as a useful or non-useful strategy after the second week of intervention while utilizing the 5-point Likert scale measuring usefulness from 1 – “Not useful” to 5 – “Very useful”.

Figure 2. Students’ opinion on usefulness of peer marking other students’ work (%)

Figure 2 shows that 35% of students discussed peer marking as useful, and the other students stated that the procedure was very useful (65%). No students discussed peer marking as useless or ineffective procedure, allowing conclusions about the overall usefulness of peer assessment conducted in the group of students.

Lavy, Paserman, and Schlosser (2011) state that peer assessment is highly useful strategy used in the class to improve students’ learning and interactions. Students’ answers to the question about the peer assessment’s usefulness support this idea in terms of students’ perception and experience.

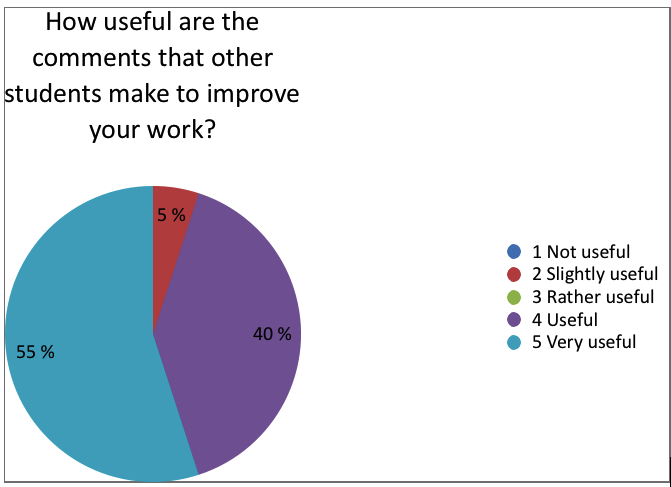

Question 4 is directly related to evaluating the usefulness of peers’ comments and assessment to improve the other students’ work.

Students were asked to evaluate the impact of peer assessment on achieving improvement with the help of the 5-point Likert scale, measuring usefulness from 1 – “Not useful” to 5 – “Very useful”. Figure 3 shows how students regard usefulness of their peers’ comments in percents.

Figure 3. Students’ opinion on usefulness of peers’ comments on students’ works (%)

The majority of students (55%) evaluated the usefulness of peers’ comments as “Very useful”, 40% of students agreed that the comments are useful, and 5% stated that the comments were slightly useful to improve the work.

The results demonstrate the students’ positive attitude to the peers’ comments, and they are important to conclude about the role of peer assessment for improving the students’ work.

According to Lurie et al. (2006), peers’ comments are usually discussed as the valuable tool to improve the other students’ performance in different areas. Answers to Question 4 are helpful to conclude that most students are inclined to perceive the peer assessment practice as effective to promote improvement of the work.

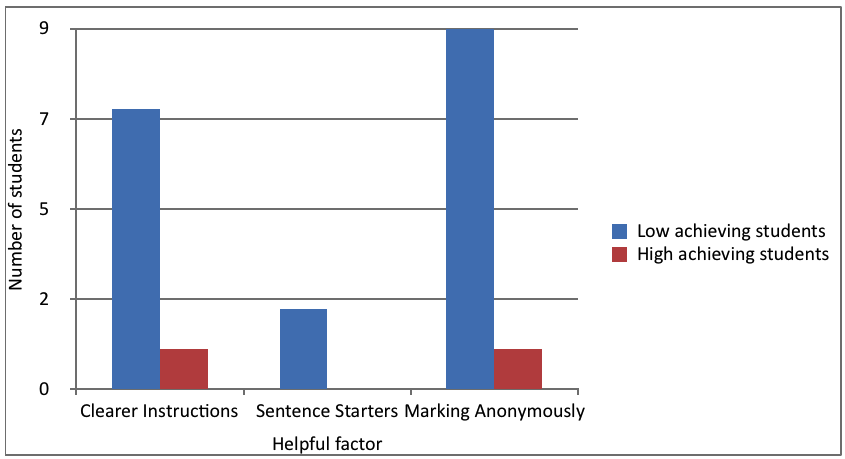

The key to discussing the improvement of students’ performance influenced by peer assessment is the focus on factors that can motivate students to improve peer marking and guarantee higher results. Question 6 asks students about factors that can improve peer marking and understanding of the requirements.

The influential factors are “Clearer instructions”, “Sentence starters”, and “Marking anonymously”. Figure 4 represents choices of helpful factors to motivate understanding by low-ability and high-ability students.

Figure 4. What helps students to improve peer marking and their understanding of the task (number of students)

According to Figure 4, about 98% of helpful factors to improve peer marking was selected by low achieving students, when only 2% of all factors were chosen by high achieving students.

The results show the interest of low ability students in using clearer instructions and making peer assessment anonymously, when sentence starters are chosen as helpful by only 10% of students.

In order to improve results in peer assessment, students need to understand the task completely, and certain factors are identified by Murayama, Perkin, and Lichtenfeld (2012) as influential for the effectiveness of peer assessment.

Thus, to guarantee improvements in the work, students need to use certain markers of factors to make the whole process of peer marking easier.

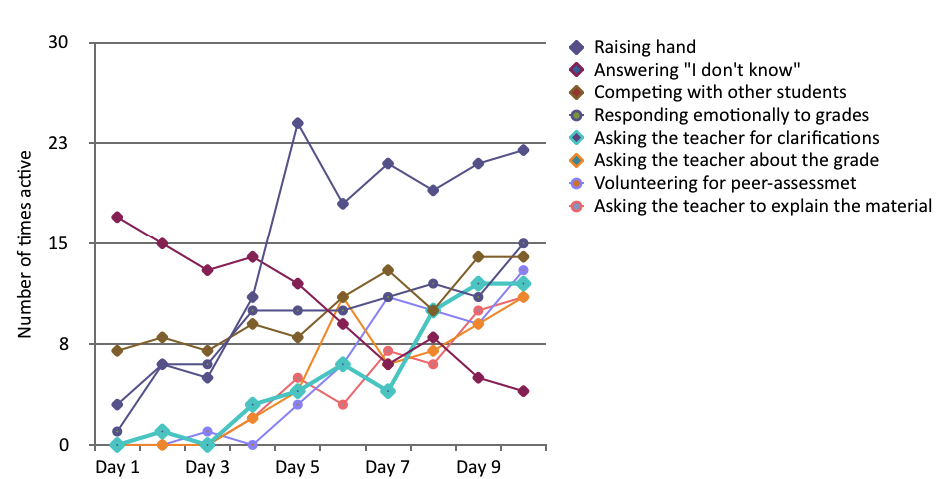

Figure 5 represents the data collected with the help of the Observation Checklist. It was important to assess the changes in students’ activity and its types during Week 1 and Week 2 in order to conclude about their motivation and involvement into peer assessment.

Figure 5. Types of students’ activity during Week 1 and Week 2 (number of times active)

As Figure 5 shows, most students expressed their willingness to participate in assessment by raising hand. The action was observed 22 times during Day 5 and about 18-23 times during Days 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

During all 10 days of the intervention, students asked the teacher to explain the material 3.9% of the whole number of instances, responded emotionally – 13.7%, competed with other students – 14.7%, asked for clarification – 11.8%, volunteered for peer assessment – 10.8%, and asked about the grade – 12.8%.

The number of students saying “I don’t know” in response to the activity reduced in 27%.

Students often need support and clarification when the new activity is integrated in the lesson, as it is noted by Falchikov and Goldfinch (2000). Thus, students asked additional questions about peer assessment and needed clarification during the first five days of the intervention.

The situation changed during Week 2, as students became more active, raising hands and asking for participation as evaluators.

Figure 6 also represents changes in the students’ involvement and interest in peer assessment with the focus on differences in behaviours of high-ability and low-ability students.

Figure 6. Activity and involvement of low and high ability students in peer marking during Week 1 and Week 2 (number of times active)

In Figure 6, the data is based on the information from the Observation Checklist. Thus, low ability students demonstrated the increases in engagement into the peer marking in about 34% during the second week, when high ability students seemed to be discouraged because their activeness decreased in 15%.

The changes in activeness of the students can be explained by the fact that the challenge of completing a difficult task such as peer marking decreased during the second week for high ability students.

According to Lai and Law (2013), the responsibility for carrying out peer assessment cannot trigger the high achievers’ initiative during a long period of time. In contrast, activeness of low achieving students increased with gaining confidence and becoming more engaged in the process.

Discussion

The results of the intervention support the prediction that peer assessment is a motivating and encouraging practice for low ability students, but it can be discussed as boring for high ability students when the challenging component of the practice is not referred to.

The qualitative data show that the high achieving students lost interest in the peer assessment during the second week of intervention. Falchikov and Goldfinch (2000) state that the key problem of peer assessment as a means to improve the score of low ability students and motivate them can depend on the scaffolding process.

The scaffolding strategies used by the teacher can be discussed by the high ability students as tiresome and irritating (Falchikov & Goldfinch 2000).

The low ability students usually do not pay attention to the scaffolding provided by the instructor; however, the manner in which the instructions are delivered may serve as the trigger for the students to develop absence of responsibility.

Thus, the qualitative data analysis points at the need to deploy a different scaffolding approach that will presuppose a more active participation of the students (both high and low ability ones) in the assignment.

According to Shin (2010), the effectiveness of peer assessment depends not only on the students’ successes in performing the activity but also on the nature of proposed tasks. In this study, tasks in reading proposed for students could be changed to make results more representative.

Thus, most high ability students demonstrate lack of enthusiasm due to the simplicity of the tasks, and it will be appropriate to create a set of assignments that become increasingly difficult as a student proceeds with their completion.

The specified approach towards developing tests will allow low achieving students to test their abilities and knowledge to the extent of their capacities and high achieving ones to maintain their academic progress in an appropriate manner.

The intervention results reveal the students’ performance was not altered significantly, but the students’ attitude towards acquiring new knowledge and skills changed positively. The purpose of the intervention was to examine peer assessment as a motivating tool for improvement in low ability students.

Quantitative data demonstrate that the students became more proactive in their participation in class activities, and they were able to cope with the fear of making mistakes which appeared to be the major barrier for showing the good performance for them.

As Wadesango and Bayaga (2013) explain, the ability grouping, as in the setting under research, leads to the development of stronger ties between students and, therefore, it leads to eliminating the fear of being considered negatively.

Comfort (2011) notes that low-ability students can develop enthusiasm in learning when they understand the task and can demonstrate immediate positive results.

The intervention conducted during two weeks allowed decreasing in the level of stress and increasing confidence in performing tasks that these students lacked before the intervention. The study shows that the adequate choice of helpful factors to motivate and support students is effective to promote their involvement and improvement.

Limitations

The study has certain limitations that restricted reliability. First, the outcomes of the study cannot be applicable to every single instance of low ability students’ training through peer assessment.

Indeed, the setting in question was specific and might conflict with the goals and assets of another educational setting as well as the adopted strategy oriented to the selected class.

In other words, the approach was tailored to meet the needs of the students that suffered from ADHD and other disorders, had a different ethnic or national background, and experienced difficulties adjusting to the school environment.

Comfort (2011) pays attention to determining general and case specific results while conducting the study. It was found that although the research was aimed at testing the idea of using peer assessment coupled with scaffolding in general, it was limited to provide results appropriate for generalising.

The number of participants is another limitation that prevents the researcher from considering the implications of the study in a wider context.

Since the research demanded the choice of a rather close setting with a relatively small number of participants, the intervention results were rather narrow and suitable for applying only to a specific group of students.

Thus, the research has its limits, and needs improvement in terms of involving larger groups of students from different environments.

Thus, it is possible to refer to the peer assessment as the intervention in several classes with low-ability students in order to compare results regarding the motivational power of peer marking to improve these students’ successes and involvement into class activities.

In terms of methodology, the tools used for collecting the data, such as the questionnaire and Observation Checklist, are rather effective to provide the qualitative and quantitative data for the further analysis.

Creswell (2005) notes that a questionnaire is the frequently used tool for qualitative studies to conduct interviews, when checklists are appropriate for observation sessions to collect the numerical data.

The limitations of these tools are in the number of questions proposed for students that could be changed depending on variations in the purpose of the future study.

In order to guarantee the anonymity and confidentiality following the British Education Research Association (BERA) Guidelines, before the experiment was conducted, teachers and departments were contacted by the author of the study and provided with the informed consent for their students to participate in the research.

Thus, the provision of complete anonymity was one of the key conditions of the study. None of the students was named directly in reports throughout the study, and no personal data were disclosed in the process of analysing the case. Therefore, the research complied with the BERA Guidelines, and it did not affect the participants negatively.

Implications for the Future Development and Research

The outcomes of the study set the premises for carrying out a major analysis of the use of peer assessment along with scaffolding at a more general level, with the focus on involving the larger number of students and possible incorporation of innovative technology, as it is mentioned in the studies by Carter (2014), Connolly et al. (2012), and Knight et al. (2014).

It is also possible to refer to the more active use of games in order to motivate students to participate in peer assessment. According to Cho, Lee, and Jonassen (2011), students can show improvement in their abilities during these games.

Therefore, it may be suggested that games along with the further evaluation may serve as an incentive for the students to achieve the better performance.

Moreover, the low scoring students can demonstrate enthusiasm when they perceive the activity as a game and can adapt to less rigid demands which can become a threat to their further performance, as it is discussed by Munro, Abbot, and Rossiter (2013) in their study.

As a result, it is important to propose a variety of peer assessment activities in a form of game and other tasks in order for high ability and low ability students to demonstrate change in their progress and motivation.

In spite of the fact that the intervention was conducted in the specific and limited setting, it is possible to adapt to the wider audience.

It is appropriate to focus on conducting the study that will incorporate students of different social, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds, and it is imperative to test the effects of peer assessment supported by the teacher’s scaffolding in the larger school area while identifying possible means for improving the current strategy.

As the outcomes of the intervention showed, the students became more aware of the stages that they passed as they acquired a specific piece of information or trained in an essential reading skill.

This important new knowledge served as a tool for enhancing the learning process for the students, therefore, allowing them to develop the necessary skills within relatively shorter amount of time and apply these abilities in a manner speedier than their previous records showed.

Thus, it is important to modify the intervention in order to test changes in the students’ motivation and improvement in a larger context.

Conclusion

The results of the conducted intervention can be discussed as successful in terms of supporting the idea that peer assessment can be used as an important motivating factor to stimulate the low-ability students’ involvement in class activities and progress.

It is possible to propose the interventions based on this one in order to implement in the school environment for improving the participation of low-ability students in class activities.

However, some of the hypotheses formulated during the research still need testing because the intervention was based only on the reading tasks, it involved the comparably small number of participants to discuss the received results as rather valid, generalised, and reliable.

Nevertheless, the results support the assumption that high ability students may lose motivation for peer assessment and studying according to the specified pattern due to the repetitiveness of the pattern, lesson design, and the overall simplicity of the assignments oriented to low-ability students.

Connolly et al. (2012) state that assignments and proposed task for peer assessment need to be highly varied in order to address the needs of students with different levels of academic achievements. The results of the intervention support this idea.

Therefore, the tools for involving the high ability students into activities during a long period of time need to be discovered in the future.

Still, the results of the intervention support the main hypothesis of the research and answer the question about the role of peer assessment to motivate low-ability students in order to become involved in the class activities and improve their progress.

Peer assessment positively affects low-ability students’ motivation and can be used to improve their performance because it is associated with cooperation and the period of adaptation to the new interesting task, as it was previously stated by Knight et al. (2014).

The results of the research also have the positive effect on teaching in terms of theoretical discussion of the nature of low-ability students’ motivation and practical use of peer assessment in order to enhance involvement and learning at lessons.

The intervention is helpful for teachers to refer again to the need of motivating not only low ability students because of the academic failures but also high ability learners who need challenging tasks.

Thus, it is important to focus on the introduction of differentiated assignments and, therefore, introduction of certain challenges to the relaxed setting associated with peer assessment if students discuss this task as too simple.

The study has also shed some light on the specifics of addressing the needs of students from different backgrounds and with different learning difficulties. More attention should be paid to developing skills in the sphere of teaching students with different potential, capacities, needs, and expectations.

Reference List

Acosta, J C & Ward, A J 2010, ‘Achieving rapport with turn-by-turn, user-responsive emotional coloring,’ Speech Communication, vol. 53, no. 9-10, pp.1137–1148.

Bryman, A 2008, Social research methods (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Burguillo, J C 2010, ‘Using game-theory and competition-based learning to stimulate student motivation and performance,’ Computers and Education, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 566–575.

Carter, C S 2014, ‘Using technology and traditional instruction to teach expository text in the sixth grade reading classroom: a quasi-experimental study,’ Instructional Technology Education Specialist Research Paper, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–58.

Cho, Y H, Lee, J & Jonassen, D H 2011, ‘The role of tasks and epistemological beliefs in online peer questioning,’ Computers & Education, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 112–126.

Cohen, L, Manion, L & Morrison, K 2011a, ‘Action research. in L Cohen, L Manion & K Morrison (Eds.), Research methods in education (7th ed.) (pp. 344–361), Routledge/Falmer. London, UK.

Cohen, L, Manion, L & Morrison, K 2011b, ‘Coding and content analysis,’ in L. Cohen, L. Manion & K. Morrison (Eds.), Research methods in education (7th ed.) (pp. 559–573), Routledge/Falmer, London, UK.

Comfort, P 2011, ‘The effect of peer tutoring on academic achievement during practical assessments in applied sports science students,’ Innovations in Education and Teaching International, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 207–211.

Connolly, T M, Boyle, E A, MacArthur, E M, Thomas Hainey, T & Boyle, J M 2012, ‘A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games,’ Computers & Education, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 661–686.

Cresswell, J W 2005, Educational research, Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Denton, C A, Tolar, T D, Fletcher, J M, Barth, A E, Baughn, S & Francis, D J 2013, ‘Effects of tier 3 intervention for students with persistent reading difficulties and characteristics of inadequate responders,’ Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 633–648.

Dominiquez, A, Saenz-de-Navarrete, J, de-Marcos, L, Fernández-Sanz, L, Pagés, C & Martínez-Herráis, J-J 2013, ‘Gamifying learning experiences: practical implications and outcomes,’ Computers & Education, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 380–392.

Falchikov, N & Goldfinch, J 2000, ‘Student peer assessment in higher education: a meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks,’ Review of Educational Research, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 287–322.

Jordan, C H, Logel, C, Spenser, S J, Zanna, M P, Wood, J V, & Holmes, J G 2013, ‘Responsive low self-esteem: low explicit self-esteem, implicit self-esteem, and reactions to performance outcomes,’ Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, vol. 32, no 7, pp. 703–731.

Knight, V F, Wood, C L, Spooner, F, Browder, D M & O’Brien, C P 2014, ‘An exploratory study using science e-texts with students with autism spectrum disorder,’ Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, vol. 28, no. 3, p. 115–126.

Lai, M & Law, N 2013, ‘Questioning and the quality of knowledge constructed in a CSCL context: a study on two grade-levels of students,’ Instructional Science, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 597–620.

Lavy, V, Paserman, M D & Schlosser, A 2011, ‘Inside the black of box of ability peer effects: evidence from variation in the proportion of low achievers in the classroom,’ Economic Journal, vol. 122, no. 559, 208–237.

Lurie, S J, Nofziger, A C, Meldrum, S, Mooney, C, & Epstein, R M 2006, ‘Effects of rater selection on peer assessment among medical students,’ Medical Education, vol. 40, no. 11, pp. 1088–1097.

Munro, J, Abbot, M & Rossiter, M 2013, ‘Mentoring for success: accommodation strategies for ELLS,’ Canadian Journal of Action Research, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 22–38.

Murayama, K, Perkin, R & Lichtenfeld, S 2012, ‘Predicting long-term growth in students’ mathematics achievement: the unique contributions of motivation and cognitive strategies,’ Child Development, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 1475–1490. Saldana, 2008

Shin, S J 2010, ‘Teaching English language learners: recommendations for early childhood educators,’ Dimensions of Early Childhood, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 13–21.

Wadesango, N & Bayaga, A 2013, ‘Ability grouping as an approach to narrow achievement gap of pupils with different cultural capitals: teachers’ involvement,’ International Journal of Educational Sciences, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 205–216.

Zingaro, D 2013, ‘Student moderators in asynchronous online discussion: a question of questions,’ MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 159–172.