The epoch of the Renaissance was marked by a conscious intellectual impulse that began in Italy in the XIV century. The culture of the Renaissance was based on the philosophy of humanism, which affirms the beauty and dignity of a person, the strength of his or her mind and will, as well as creative possibilities. The revival of interest the in ancient heritage and return to antique forms in art included a realistic manner in architecture with the development of linear and light perspectives. This paper aims at examining how the Renaissance architects used the perspective drawing to communicate and explain architectural constructions.

Emerged in the Antiquity and lost by ancestors, the linear perspective drawing was introduced by Brunelleschi, Alberti, and other prominent architects, who used a vanishing point to follow accuracy in proportions and make paintings realistic.

Architecture occupied a leading place in the Renaissance art, which was expressed in simplicity and tranquility of volumes and shapes. The perspective was understood as the science of imaging objects on a surface such as they are perceived by the human eye. The linear perspective gave the possibility of constructing three-dimensional elements in two-dimensional space, developing more detailed forms (Carpo and Lemerle 13).

It should be emphasized that Antiquity and the Middle Age periods solved the problem of finding a volumetric form without interrupting a construction. From the very beginning and through the entire Renaissance period, the principle of artistic individualism and reference to ancient forms remained popular. The rational forms appeared with visually clear boundaries – the key geometric shapes and bodies in the Renaissance architecture were a square, a rectangle, a cube, and a ball.

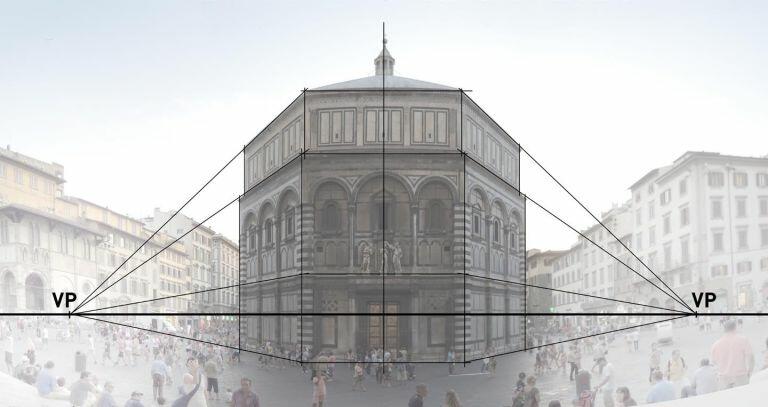

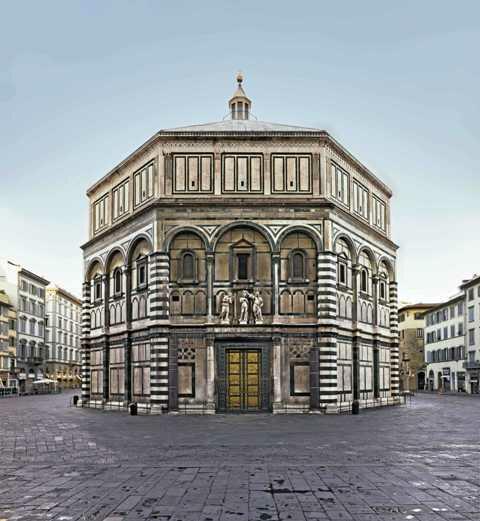

The first exact formulation of the laws of building perspectives belongs to Filippo Brunelleschi, who discovered the vanishing point on the plane, into which all parallel lines were to be directed (Pictures 1-2). In addition, this architect guessed the scale by calculating the ratio of the length of the figure to the length of the projection in the picture, depending on the distance from the picture plane (Panofsky 5). Brunelleschi made these discoveries based on the thorough analysis and execution of drawings of ancient Roman buildings.

In order to draw the sketch of the mentioned building, the architect used a mirror and mathematically calculated the distance between the objects. Indeed, the review of the schematic view of Brunelleschi’s Florence Baptistery shows that all proportions are correct. The realistic appearance is also demonstrated by the lines that connect left and right sides with the central points at different levels. The scheme shows that the vanishing points are at the same level, which is the main basis of the drawing.

Thus, Florence Baptistery may be regarded as perspectively accurate since all the lines are well-coordinated. It can be supposed that Brunelleschi’s perspective allows treating the perspective not only as a method of organizing the space of the plane but also as a way of shaping the perception of the audience. In others words, it seems that the artist identifies several points, thereby setting the distance to the picture plane, which determines the location of a viewer and forms his or her perception.

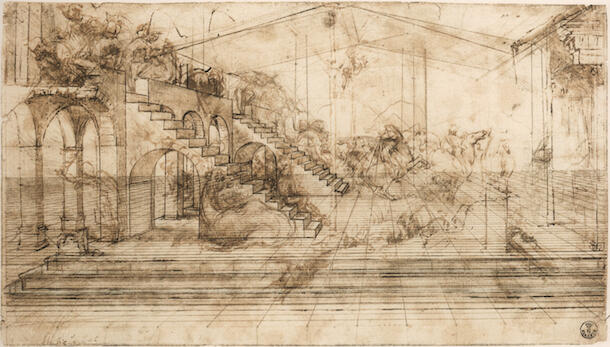

In his turn, Leon Battista Alberti spoke of a picture of the plane as a transparent surface to represent forms of visible objects on this surface as if it were transparent glass (Carman 23). Through the latter, a visual pyramid passed at a certain distance, light, and position of the center of the drawing (Picture 3). Alberti suggested using a grid on glass when drawing from life to build perspective through distance points where the diagonals of the squares of the floor or the square converged.

The plane solutions of two-dimensional space were replaced by those that create the illusion of depth, allowing the picture and the building to “vibrate” and represent the perspective. All these qualities of the plane help to influence a viewer in different ways – the effective perception of architecture and plane was replaced by the visual perception. The architects became more contemplative and designed a new architectural form and space, thus refocusing on the concept of space rather than place.

In the history of architecture, there are many examples of drawings and layouts – models of natural and large scales executed in order to verify the artistic and design features of structures. The epoch of the Renaissance brought a new philosophy to architectural design, and the construction of a linear perspective became an organic phenomenon (Carpo and Lemerle 51). There was a process of developing a plane that becomes part of the architectural form. The planar principle of the image gave rise to the perception of volume, the illusion of depth, the instrument for the achievement of which was a linear perspective.

An example of this is the rusticated facades of the palazzo or the painting of churches, which organically continued the volumetric details of the eaves or domes. Thus, Alberti, Brunelleschi, and other architects achieved the unity of volume and plane in an attempt to make buildings look more realistic and, at the same time, reflective of the Renaissance.

The constructive solution of vaults and domes remained the main technical and artistic challenge. The closed arches and domes, which leave a lot of space for murals, were especially popular in combination with the ancient and medieval experience (Panofsky 38). At the same time, it should be stressed that the Renaissance tried to overcome the massiveness and simple accumulation of volumes. For example, Brunelleschi’s Florence Baptistery can be regarded as a revolutionary building that attracted by its simple yet solemn lineament. To facilitate the construction in the system of vaults, various additional elements were used that were left open and sometimes interpreted as details of the artistic solution.

The compositional effects of perspective drawing were differently understood and represented by painters and architects in the epoch of the Renaissance. In particular, in his On Drawing, Alberti noted that, for example, pavement could characterize the approaches of the mentioned artists (Puttfarken 69). The difficulty and obscurity of presenting pavement in the context of perspective made it unknown to painters, who tried to depict objects in their natural forms. In other words, painters viewed perspective as a part of the picture, while architects followed “the principle of perspectival unity and coherence” (Puttfarken 70). The latter means that every object should be constructed in such a way as to ensure that the whole project is observed from one point.

The key difference between the view of architects and painters on using the strategy of perspective is that the former tried to measure all figures and forms, and the latter pursued the goal of mere provision of drawing as a part of the real world. In this regard, the very idea of perspective unites both architects and painters and acts as the main similarity. In order to organize figures, architects measured seven movements, including left, right, forward, backward, down, up, and around in relation to other objects.

This points to one more difference – the attitude to the use of perspective. If architects strived to strictly follow the rules of the perspective theory, painters targeted its practical in terms of the material condition. Thus, Alberti stated that these two approaches should be different since they focus on various aims – central and frontal perspectives to portray the pictorial world.

The representation of space and perspective constructions was also used by Paolo Uccello, an Italian painter of the early Renaissance. This prominent painter focused on the perspective as a complex reversal of numerous figures. The perspective was understood by Uccello not just as an artistic device but as a general law for depicting nature and art. For example, a fresco in Santa Maria Novella church in Florence shows a method of perspective construction according to plans and sections, right up to the top of the eaves and floors (Picture 4).

With the help of the intersection of lines as well as shortening and moving to the vanishing point, Uccello achieved results in overcoming difficulties with arranging the figures on the plane on which they stand. He also found a way to build curves for demolitions and arches of the cross vaults and a reduction in ceilings with beams going deep, to build round columns at the corners.

In turn, Piero della Francesca, an innovator in the field of perspective figures, was obsessed with plastic modeling and deep space, which are characteristic of his compositions. For example, one may discuss a vivid example of perspective drawing – the Brera Madonna (Picture 5). In this painting, Francesca was the first Italian architect of the 15th century to depict Madonna and the surrounding saints in the interior of the church. It is possible to note that the architecture of the traditional temple is rather luxurious.

The whole composition is close to symmetrical one and unfolds in space in a vicious circle, looking like an immaculate sphere. In this architecture, the elevation of the plan is revealed in harmonization of people with the environment and perspective drawing lines that invisibly lead to the vanishing point. The identified artist created a glaze technique, which has become decisive for his style, which expressively conveys the atmosphere of the painted design (Banker 165). Francesca managed to create the illusion of the depth of the depicted space, so that the group of saints was placed not in the apse yet behind it.

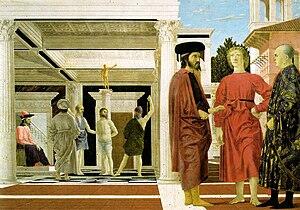

The Flagellation of Christ is one of the most mysterious paintings of Francesca, resembling a diptych in its composition. Visually, the piece consists of two parts, which, at first glance, are not related to each other (Picture 6). There is the scene of flagellation presented on the left side of the canvas, and a viewer sees a group of three men quietly talking on the right. This combination of cruelty and ordinariness gives the plot a dramatic sense and makes a new look at what is happening. In order to visually separate one part from another, the artist used the technique of a linear perspective, placing Christ and his executioners in the depth of the portico (Banker 120).

The rhythmic alternation of vertical and horizontal lines forming the floor, ceiling, and columns creates a frame, beyond which the Trinity is located, which is clearly oblivious to what is happening behind their backs. Compared to works of Uccello, those of Francesca have a more intimate effect, which is achieved by dramatic and solid figures perceived by a viewer closely.

Today, architects also use perspective drawing to transform the reality into appearance, yet they are more focused on psychological impact rather than divine plots. There are various applications of perspective drawing in the modern world, beginning from painting to 3D computer games. It should be stressed that with the rapid development of technology, perspective drawing opened more opportunities for those who want to use it.

For example, computer-aided design (CAD) software assists in calculating required distance between figures, setting trajectories, and pointing to mistakes. As for the future of perspective, one may state that it can be utilized to project innovative buildings as objects of arts or for living based on three-dimensional drawings. The creation of futuristic cities and computer games is another potential development area.

In conclusion, the Renaissance architects used the perspective drawing not only as a method of organizing the space but also as a way of organizing the audience perception. The architects set the distance to the drawing plane, which determined the location of a viewer and formed his or her perception. In general, the perspective drawing was applied by that period architects as the representation of humanistic ideas and great abilities of people. Nowadays’ perspective drawing targets the psychological impact and practical use, focusing on 3D technology and projects of futuristic cities.

Appendices

Works Cited

Banker, James R. Piero Della Francesca: Artist and Man. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Carman, Charles H. Leon Battista Alberti and Nicholas Cusanus: Towards an Epistemology of Vision for Italian Renaissance Art and Culture. Routledge, 2016.

Carpo, Mario, and Frédérique Lemerle. Perspective, Projections and Design: Technologies of Architectural Representation. Routledge, 2013.

Panofsky, Erwin. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art. Routledge, 2018.

Puttfarken, Thomas. The Discovery of Pictorial Composition: Theories of Visual Order in Painting 1400-1800. Yale University Press, 2000.