Abstract

The present study is the actual replication of the study of Chang (2010) on the analysis of developmental pragmatics and evolution of speech acts of L2 learners with the increased proficiency levels in English. The speech act of apology was analyzed with the help of tools and analysis instruments similar to those of Chang (2010), but with the introduction of a new sample of L2 learners with the levels from moderate to proficient.

The purpose of the study was to enlarge the body of knowledge in developmental pragmatics and to investigate the order of linguistic acquisition in combination with the theoretical account of interlanguage pragmatics.

The article specifically deals with the acquisitional pragmatics field, investigating the development of such pragmatic competencies as expressing an apology in the L2 at various proficiency levels. The conclusion reached in the present study is fully consistent with the replicated study of Chang (2010) on the direct impact the increase of linguistic proficiency produces on the speech act competencies and variability.

Introduction

The current attention to interlanguage pragmatics results in the necessity to conduct deeper, more grounded and expanded research in the field of language acquisition and pragmatic performance of L2 learners. There is much research being held nowadays in the field of developmental pragmatics, though the field itself is rather young, and findings in the discussed area of scholarly attention are scarce.

There is much incongruence between the actual pragmatic performance and the development of pragmatic competence, as it is discussed from various angles in the currently available studies. Hence, more attention is now paid to the developmental pragmatics as a science able to help unveil the hidden cognitive and learning processes occurring in the L2 learners’ knowledge base during the English language studies.

The most significant findings in the field pertain to the studies of apology, request, and gratitude expression evolution by L2 learners.

However, only students with high proficiency levels have so far been subject to research; different age groups and specific speech acts have to be researched to achieve a much more profound understanding of the evolutionary processes in self-expression and variability of speech acts of L2 learners in the process of language acquisition.

The present study is the continuation of Chang’s (2010) work on identifying the apology expressions found in the responses of Chinese students.

While the focus of the present study is on the same study design and instruments, it offers a clear step forward in enriching the idea of developmental pragmatics because it intends to provide data on other age groups, enabling the further comparison and generalization of results in communion with the results of Chang (2010).

Literature Review

The present study takes the interlanguage pragmatics findings and interlanguage competencies as the theoretical framework for the research.

The works on which the theoretical and practical inferences are based are the one of Cheng (2005) that represents a cross-sectional study of interlanguage pragmatic development of gratitude speech acts, the study of Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1986) dedicated to the theoretical and applied domains of pragmatic failure, and the work of Cohen (2004) explicitly explaining the subject of developmental pragmatics and pragmatic ability of L2 learners.

Such researchers as Bataller (2010) who investigated the immersion technique as a contributing factor to the development of interlanguage competence, and Trosborg (1987) discovering the importance of sociolinguistic competence in the formatting of communicative appropriateness awareness have also contributed to the theoretical basis of the present research.

The book of Trosborg (1995) on interlanguage competence offered much theoretical material for consideration in the framework of the present research. The scholar decomposed the notion of the communicative competence and outlined the main components contributing to the formation of interlanguage proficiency for L2 learners.

These essential components include the linguistic competence (the mastery of the target language code), the socio-linguistic competence (informing the L2 learner about the socio-cultural rules of the native-speaking society), the socio-pragmatic competence (enabling the L2 learner to assess the appropriateness of contextual meanings), and the strategic competence (helping the speaker to bridge the gaps in language knowledge and fluency by other communicative strategies) (Trosborg, 1995).

Some other findings of Trosborg (1995) are of great value for the whole field of developmental pragmatics research; the author outlines the psycholinguistic competences that enhance the L2 learner’s interlanguage proficiency acquisition, including the knowledge and skills component.

Methods

Participants. As the purpose of the present work was not to create a new body of knowledge on the pragmatic development of L2 learners, but to extend the existing body of research on the issue, a group of L2 respondents was chosen for the collection of qualitative and quantitative data for the study.

The present group of 12 students represents a new age category as compared to the study of Chang (2010), thus enabling the comparison of results obtained in the present study with those of the original study’s author. There are various levels of proficiency within the group resulting from various backgrounds of respondents (China, Taiwan etc.) and hours per week previously allocated to the English language studies.

The proficiency of the respondents is from intermediate to advanced (according to the researcher’s estimate), and they represent older ages than the respondents used by Chang (2010) do. The respondent sample is based on Taiwanese and Chinese immigrants to the USA, mostly female (n=11), with only one male.

The respondents have been living and studying English in the USA for a different number of years (from 1 to 22 years), and started studying English at school in their native settings at the age of 10-17 years old. Only one woman reported studying English on her own, at home, from 32 years old; she is 46 years old, which implies that she has been studying English for about 14 years until the moment of the study.

To assess the proficiency levels evident in respondents participating in the present study, one can see the self-reported proficiency levels indicated by them in the questionnaires, systematized according to the respondents and categories of competencies. The figures in the present table should be decoded the following way: 1 – Very poor; 2 – Poor; 3 – Fair; 4 – Functional; 5 – Good; 6 – Very good; 7 – Native-like.

Table 1. Proficiency Levels of Respondents.

Instrument Design. Since the present study replicates the study of Chang (2010), the instrument design of discourse completion tasks has been borrowed from the original study. The construction of tasks included consideration of participants’ understanding of scenarios and their ability to respond to them adequately.

The scenarios were altered slightly, eliminating the figure of the teacher and substituting it by an abstract high-status partner, either an elderly person or some other respectable acquaintance. However, the four scenarios were generally retained and included bumping into people, losing a borrowed book, being late or rude to someone.

Each scenario was used two times, with one variant including the peer relationship of a student to another student, and the second variant containing the student – high-status person relationship. Description of context is provided to each scenario, with the opportunity to give the answers to open-ended role-play questions. The unified set of scenarios applied in the present work may be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Scenarios for the discourse completion task questionnaire.

Data Collection. The method of data collection was chosen similarly to the one of Chang (2010) – it is the discourse completion task questionnaire (DCT). The DCT is still seen as the most effective tool for the students to produce an L2 apology reflecting their linguistic proficiency, and for teachers to investigate the pragmatic competency in L2 apology.

The DCT also involves written replies, which adds material for consideration in the process of data analysis, driving some competence conclusions from the given replies and grammar, spelling and other mistakes students may make.

The first stage of the DCT questionnaire fulfillment included the completion of the form with biographical data pertaining to the study; the students were to indicate the country of their birth, the period of studying English both at home and in the USA, and finally they had to state by which means they thought the prime portion of language acquisition occurred in their life.

The second portion of data they needed to provide was their self-assessment on four competencies, including writing proficiency, speaking fluency, listening and reading proficiency as well.

The DCT for the present study was distributed to participants asked to write down that they would respond in English to eight role-play situations. Similarly to Chang (2010), no rejoinder was available for the students. The percentage of replies equals 100%, expect the second respondent who did not indicate her proficiency levels in the studied competencies.

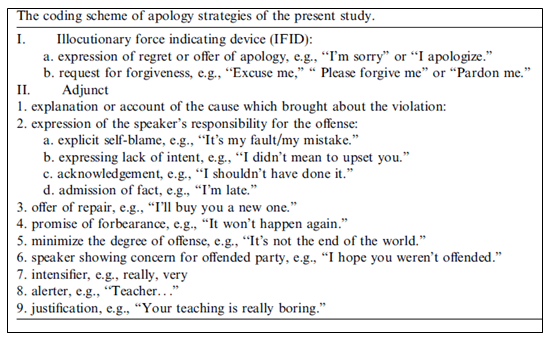

Data Analysis. The theoretical findings on analyzing the speech act of apology were used to generate the coding scheme for analysis; Chang (2010) consulted a professional in the sphere of coding, thus ensuring the unified coding scheme for speech act evaluation, and ensured the reliability rate of 91%.

The discussed coding scheme completely fits the requirements of the present study replicating the one of Change (2010), therefore the same coding scheme will be used; it may be seen in Table 3.

Table 3. The Coding Scheme of Apology Strategies of the present study.

Source: from Chang (2010), p. 413.

Upon coding the data, the researcher intended to conduct similar analysis procedures as those ones applied by Chang (2010) – the frequency of apology strategies usage, and the content of strategies used by respondents. To assist the first data analysis task, all apology strategies were grouped into ‘IFID’ and ‘Adjunct’ categories, according to the pattern utilized by Rose (2000).

Frequency of each strategy’s usage was calculated on the background of the whole number of strategies used by all respondents in all situations. Secondly, the frequency of each strategy’s occurrence in the responses of each participant was counted to identify the most frequent and widespread apologies.

Finally, the number of apologies used as well as the number of strategies used in general by category was calculated to generate a rating scale of popularity and usage of certain apology strategies by the indicated group of respondents.

To answer the second question, the researcher needed to assess the order of each strategy’s usage in certain proposed scenarios. In this case, each scenario was researched for the number of various strategies applied by respondents, with the proper summary of the results on the expansion of apology repertoire with the growing proficiency level.

It was necessary to disregard the contextual requirements of the scenario offered for the sake of answering the present research question.

Therefore, ignoring the situational context, the variety of strategies was arrived at by using two means also borrowed from the study of Rose (2000) – first of all, the usage of each certain apology was counted across all eight scenarios, with the proper rating scale generation to see the emergence of each strategy in the whole questionnaire context.

Secondly, the occurrence of each particular strategy was assessed in each separate scenario, to investigate the patterns of occurrences and to produce relevant inferences on apology usage aimed in the present study.

Discussion of Results

Frequency of apology strategies. As it has already been mentioned, the approach generated by Rose (2000) and borrowed by Chang (2010) is also applicable for the present study; the apology strategies were broadly divided into two categories, IFIDs and adjuncts, to calculate and compare their usage in all scenarios disregarding the context.

The analysis of coded qualitative data showed that the number of IFIDs used is really high (66; 28.4%) as compared to any other apology used. However, it is also evident that adjuncts are used by the present group of respondents are also varied, and they are utilized in multiple contexts, with the most popular ones being the intensifier, repair offering, and concern (13.3%, 12% and 10.4% respectively).

This finding supports the conclusion of Chang (2010) that students with higher proficiency levels employ many more adjuncts in their expression of an apology than smaller children and people with lower proficiency levels do. It is hard to say whether the usage of the discussed adjuncts is influenced by the contextual specificity of scenarios, since no tendency of such kind could be observed, as one can see in Table 4.

Table 4 also shows the distribution of each strategy in each given scenario, giving the figures from 6 to 12 strategies applied in each scenario. The figures 6 and 7 prevail in the majority of scenarios, leaving only scenarios 4 and 5 with the largest number of apologies invented by the respondents.

Scenario 6 shows the implementation of 8 various strategies, which implies that it is the third most diverse situation for respondents to make an apology.

Though the results are not the direct breakthrough in the number of apologies investigated by Chang (2010) and showing that high school students gave from 8 to 14 different apologies in each scenario as compared to schoolchildren of the 3rd grade who stopped at 8 strategies in scenario 8 being the most diverse in responses, it is still clear that the evolution of apology implementation is in place.

The present finding may be derived from the fact that the respondents with higher proficiency levels managed to use from 3 to 5 strategies to respond to each scenario, which implies a certain measure of progress in self-expression.

However, as it has already been mentioned, the IFID type of apology has been detected as the most frequently emerging reaction, which is consistent with the findings of Chang (2010) stating that IFIDs were dominant in all grades researched, and were used indiscriminately often by representatives of each focus group.

The fact that they are common for all groups investigated by Chang (2010 and in the present study presupposes the universality and the first apology coming to mind to all L2 learners (which is also natural for native speakers as well).

However, the correlation of the 1st IFID “I am sorry” or “Sorry” met 63 times in the responses with only 3 occurrences of the 2nd IFID “Please forgive me” also draws a parallel with the former research of Chang (2010) indicating it to be rare and practically non-occurring in the written and oral practice.

Table 4. Comparison of the use of apology strategies in eight scenarios.

Proceeding to the discussion of adjuncts, one has to note that they are surely both proficiency and situational, since the inventory of apologies used in the scenarios 7 and 8, as compared to the scenarios 1 and 2, will be completely different for all group members disregarding their proficiency level.

Thus, for example, the most commonly met strategy for the scenario 7 and 8 is concern for the bumped person, with the majority of respondents showing equal concern for the elderly person and the close friend. The present study provides further evidence of this fact because it shows the incidence of concern apologies usage the highest in the 7th and 8th scenarios (10 times in each).

Sub-strategies of ‘admission of the fact’ and ‘lack of intent’ were commonly used in the scenarios 1 and 2, which is also consistent with the findings of Chang (2010).

The figures 10 and 11 for acknowledgement and lack of intent apologies respectively show that the respondents from the present respondents’ group applied the apology revealing their responsibility for the incident practically in every situation, though not every respondent did that.

Intensifier being on the second place after apology and regret shows that the higher proficiency level group often adds intensifiers to the apologies voiced, which is fully consistent with the findings of Chang (2010) stating that the increase of intensifier usage was observed only with higher grades of respondents, being totally unpopular with the 3rd grade students, and being much more common in the 10th grade.

Table 5. The comparison of respondents’ usage of various apology strategies.

The content of the apology strategies. Proceeding to the discussion of the apology content, one needs to note that the regret-apology forms were mostly used in 90% of situations first, then followed by other categories of apologies; they were used in the forms “Sorry”, “I am sorry”, “I am so sorry”, and “I am very sorry”.

The phrase “I apologize” was met only twice, which implies the indisputable popularity of “sorry” and its derivatives in voicing an apology. No misinterpretations were noted in the responses of the discussed sample, with no usage of ‘excuse me’ phrase in the described scenarios.

The strategy of ‘admission of the fact’ is used more often in all scenarios by the present group of respondents, which supports the hypothesis of Chang (2010) on the evolutionary usage of apology forms by students with higher proficiency levels.

As a matter of fact, admission of the fact is recognized as a more complex form of an apology, hence its more frequent usage supports the idea of the findings arrived at in the present group being a logical support and continuation of Chang’s (2010) research.

The ‘lack of intent’ strategy was also used predominantly in the scenarios 1 and 2, as well as 7 and 8. The overwhelming incidence of that strategy’s correct usage supports the idea of the developmental patterns of apology as a speech act of L2 learners.

Table 6. Frequency of apologies implemented by respondents in all scenarios.

The innovative apology tool of older groups – emergence of avoidance strategies. The present study revealed an interesting tendency in the responses of the present sample that had not been previously investigated by other researchers. While no rejoinder was available for the usage in the DCT questionnaire generated for the present study, no deviations from the coding scheme were expected.

However, the incidence of avoidance strategies was viewed in several scenarios applied by 3 respondents. One of the respondents reacted the following way to the scenario 4, when the friend of hers heard her complaining about the poor English she had: “Sorry, I have to go”.

It is a clear avoidance of the need to give apologies. Another situation was observed in the scenario 8: “Oh, I am so happy to see you that I bumped you. We have to see each other more often!”. It is the strategy of turning the offence into a humorous situation and avoiding saying anything similar to an apology.

Scenario 4 also showed several responses similar to assuming that the friend Judy did not understand any of the complaints because her English was really bad, which means that no fault in the situation was detected by respondents.

Avoidance of complaints is also widely spread in scenarios 5 and 6, where the respondents voiced their hope that nobody had noticed their absence and lateness. 3 respondents stated that in case nobody asked them about lateness, they would just join in and say nothing.

Such absence of the wish to apologize may be presupposed by the age of respondents, experience in life and the unwillingness to pose themselves in a weaker position by searching explanations, justifications, and offering repairs.

However, another most common strategy used in the same scenario was offering to pay the bill, without even mentioning an apology, which notes the practical attitude to lateness, and the wish to compensate the fault with food and drinks, and not an apology for the offense and lack of respect.

Conclusion

The present study represents the continuation of research in the field of L2 learners’ communicative competency development research on the example of the speech act of apology.

The findings refer to the developmental processes in the apology reflection field of Taiwanese and Chinese L2 learners of moderate to high proficiency levels, and contribute to the findings of Chang (2010) on the expansion and variability of apology strategies applied by various proficiency groups of L2 learners.

The study was based on the written DCT data collected from L2 learners in the classroom, taking a step forward in the interlanguage pragmatic development research. The discussion of results obtained in the course of the present study indicates that students extend and enrich their apology strategies, use more complex strategies more readily in various scenarios with the higher proficiency levels of English knowledge.

However, the research produced seems rather isolated from the common body of research in the developmental pragmatics, as the necessity to introduce the longitudinal and cross-sectional studies in a combination was repeatedly indicated by researchers and practitioners of the field.

Lack of the ability to compare the L2 data with a similar sample of L1 speakers represents the major limitation of the research, thus preventing it from generalizations. Context specificity research is also potentially beneficial for acquiring better understanding of the internal incentives of L2 learners to choose the apology strategies, so it has to be attributed more attention in the future research.

References

Bataller, R. (2010). Making a Request for a Service in Spanish: Pragmatic Development in the Study Abroad Setting. Foreign Language Annals, Vol. 43, Iss. 1, pp. 160–175.

Blum-Kulka, S., Olshtain, E. (1986). Too many words: length of utterance and pragmatic failure. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, no. 8, 165–180.

Chang, Y.- F. (2010). ‘I no say you say is boring’: the development of pragmatic competence in L2 apology. Language Sciences, no. 32, pp. 408–424.

Cheng, S.W. (2005). An exploratory cross-sectional study of interlanguage pragmatic development of expressions of gratitude by Chinese learners of English. PhD Diss., University of Iowa. Retrieved from https://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/104/

Cohen, A.D. (2004). The interface between interlanguage pragmatics and assessment. Proceedings of the 3rd Annual JALT Pan-SIG Conference. May 22-23, 2004. Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo Keizai University.

Rose, K. (2000). An exploratory cross-sectional study of interlanguage pragmatic development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, no. 22, pp. 27–67.

Trosborg, A. (1987). Apology strategies in natives/non-natives. Journal of Pragmatics , no. 1, pp. 147–167.

Trosborg, A. (1995). Interlanguage Pragmatics: Requests, Complaints, and Apologies. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.