Outbreak of infections is a major threat to public health. Without close monitoring of public health, controlling infections in their initial stages would be complicated and result in epidemics and pandemics. Therefore the healthcare stakeholders must have accurate data regarding public health to mobilize necessary resources to respond to infections in time and eliminate threats that undermine public health. Accurate collection of data requires the employment of effective public health surveillance (PHS). This practice gives the healthcare stakeholders an accurate picture of public health practice and enables them to identify any potential threat that requires urgent interventions.

PHS draws its foundational basis from the principles of epidemiology. This type of surveillance is a structured collection and analysis of data relating to public health that is essential for planning and implementing mechanisms for preventing and controlling infections (Chiolero and Buckeridge, 2020). The practice of public surveillance is a continuous process that aims at constantly monitoring public health for any potential threat that can lead to an outbreak. In addition to monitoring emerging infections, data relating to factors that may cause an outbreak of infection is collected during the process.

Data on adverse practices is essential for the healthcare stakeholders to determine the trends in public health and take necessary precautions in handling negative trends that may lead to a health crisis. Public surveillance systems aim to give detailed data regarding a population, including the geographical and temporal trends defining the population (Chiolero and Buckeridge, 2020). Other factors considered during the process include the socioeconomic practices of the population and their clinical characteristics. Additionally, the data collected aims to give details on the characterization of the infection and the changes in its occurrence. The data is often as detailed as possible to give the stakeholders an accurate perception of the health situation of a population.

PHS has been categorized into active, passive, and sentinel surveillance. Active surveillance is often employed when studying a new infection is likely to cause an outbreak. It involves going to the affected population, finding the active cases, and learning how it affects the population (Gervasi et al., 2019). This type of surveillance requires more resources and its main objective is to eliminate the infection within a reasonable time before it spreads to other populations. Passive surveillance involves using the available data to study a particular infection. Unlike active surveillance, passive surveillance involves monitoring the reported cases without going to the field to study the infection (Gervasi et al., 2019). Data from passive surveillance is often provided by healthcare providers interacting with the affected people. For passive data to be accurate, there is a need for all the reports to be consistent. Inconsistences may lead to understanding the problem, causing a healthcare crisis.

Lastly, sentinel surveillance is often employed when high-quality data is needed that cannot be provided by passive surveillance. It is often used when the reports concerning an infection are highly inconsistent (Huyen et al., 2018). This type of surveillance involves selecting specific institutions to research the infection on a specific population to provide relevant data that provides accurate information on the severity of the concerned problem.

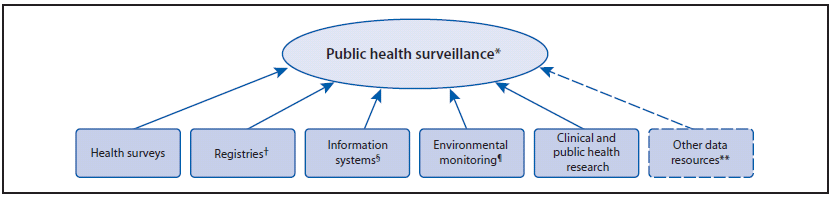

The objectives of public health surveillance tend to differ depending on the type of information needed by the healthcare stakeholders. However, before implementing the practice, having clear objectives is essential to ensure that accurate data is collected. There are various data collection methods during public health surveillance, including environmental monitoring, surveys, notifications, and registries (Introduction to public health surveillance, n.d.). Environmental monitoring involves a range of processes, including analyzing the pollution levels of the geographical location of the population. Additionally, healthcare agencies may monitor the insect and animal vectors within the region to determine the presence of any harmful viruses or parasites. Surveys involve collecting necessary information regarding the subject of interest from a population sample (Introduction to public health surveillance, n.d.). The responses of the sample represent the data of the entire population.

Notifications involve data collected from reports made by people affected by a particular health condition. This data collection form is often confidential, and the victims can never be disclosed. Lastly, registries involve tracking the health trends of individuals from the population under surveillance for any form of patterns that may signal the emergence of an infectious condition (Introduction to public health surveillance, n.d.). Using registries for data collection is a continuous process that requires close monitoring of the persons of interest for a significant period.

The process of public health surveillance is essential in various ways. Firstly, it enables healthcare stakeholders to assess a population’s health status to understand the existing healthcare conditions (Haron, 2020). Moreover, public health surveillance is essential in understanding the trends in infections and changes in healthcare practices (Haron, 2020). Causative agents of infections are subject to mutation and tend to become more resistant to treatment. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend the transformation of infections and how they affect public health. Moreover, constant surveillance of infections is essential in keeping the history of the infection to predict various variances that may arise in the future. The transformation and mutation of infections influence the development of variances that may pose a serious threat if not analyzed in time.

Secondly, public health surveillance provides essential data for planning and monitoring infection and its effects on a population. This data is vital for making relevant policies aimed at improving public health practices and the quality of healthcare services (Haron, 2020). Additionally, the data obtained from the surveillance is essential in determining the effectiveness of interventions initiated to improve healthcare practices. The relevant healthcare stakeholders may use this data to identify the areas that require priority setting and the most effective practices that can be implemented to improve healthcare.

Thirdly, surveillance provides data that helps in the early detection of infections, thus enhancing the government’s ability to initiate urgent preventive mechanisms. Early detection of infection is vital to reduce the effects of the infection on the people and prevent the healthcare system from being overwhelmed (Zimmerman et al., 2022). Furthermore, public health surveillance enables the government to estimate the size of the healthcare problem and determine the resources needed to handle the problem effectively. Without accurate information about the infection and the population, it may be difficult for the relevant authorities to determine the effective mechanisms to implement, hence creating a loophole for the problem to accelerate.

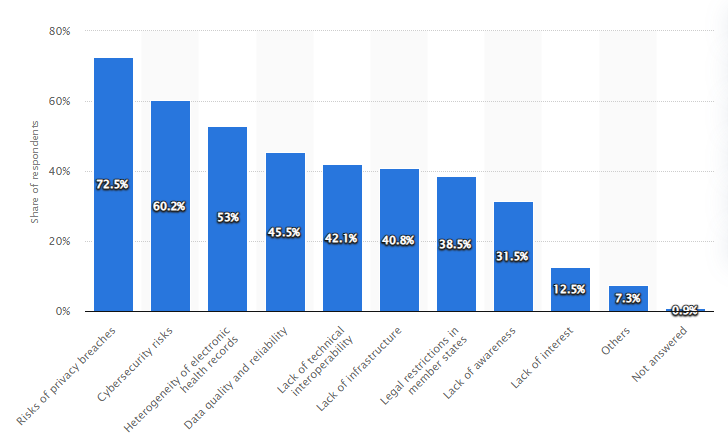

The process of data sharing in public health is often faced with various obstacles that undermine data accuracy and the process’s effectiveness. These barriers can be political, technical, ethical, legal, economic, and motivational (Kaewkungwal et al., 2021). The political barrier to health care data sharing involves inherent policies and guidelines that govern the healthcare services of a particular demographic. Some policies hinder effective data sharing due to a lack of political will to share data. Additionally, political barriers involve a lack of trust and commitment from the authorities to advocate for data sharing.

Technical barriers include system failure, which may corrupt the original data. Furthermore, the lack of enough security mechanisms to prevent data loss is another significant technical problem that undermines data sharing in public health. Ethical barriers include a lack of willingness from the parties involved to share credible information (Kaewkungwal et al, 2020). Most parties tend to assess the risks and benefits associated with data sharing before deciding to engage in data sharing. If the risks outweigh the benefits, many parties decide not to engage in data sharing. Legal problems hindering data sharing involve implementing restrictive laws regarding data collection, parties’ consent, and data security.

Additionally, there are strict copyright laws that make it difficult to share data. Economic barriers involve the costs of collecting and storing the data. Some of the data collection methods in public health tend to be expensive. Lastly, the motivational barriers involve a lack of incentives and rewards for those willing to share data (Kaewkungwal et al., 2020). Additionally, disagreements on the various data-sharing methods between the involved parties are a common motivational problem that hinders data sharing in public health.

In conclusion, public health surveillance is an essential process that facilitates effective planning and control of infections. This process allows early detection of infections thus preventing outbreaks that are likely to overwhelm public health systems. For public health surveillance to be effective, it must be conducted continuously to provide the relevant authorities with the accurate information about the health status of the public. Furthermore, it is essential that various barriers that hinder sharing of public health data are addressed to facilitate flow of accurate information.

Reference List

Chiolero, A., and Buckeridge, D. (2020) ‘Glossary for public health surveillance in the age of data science’, J Epidemiol Community Health, 74(7), 612-616. Web.

Gervasi, V., Marcon, A., Bellini, S., and Guberti, V. (2019) Evaluation of the efficiency of active and passive surveillance in the detection of African swine fever in wild boar. Veterinary Sciences, 7(1), 5. Web.

Haron, N. H. (2020) The importance of enterprise architecture in public health surveillance system. Web.

Huyen, D. T. T., Hong, D. T., Trung, N. T., Hoa, T. T. N., Oanh, N. K., Thang, H. V., and Anh, D. D. (2018) Epidemiology of acute diarrhea caused by rotavirus in sentinel surveillance sites of Vietnam, 2012–2015. Vaccine, 36(51), 7894-7900. Web.

Introduction to public health surveillance (n.d) Web.

Kaewkungwal, J., Adams, P., Sattabongkot, J., Lie, R. K., and Wendler, D. (2020) Issues and Challenges Associated with Data-Sharing in LMICs: Perspectives of Researchers in Thailand. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103, 1, 528-536, Web.

Zimmerman, D. M., Mitchell, S. L., Wolf, T. M., Deere, J. R., Noheri, J. B., Takahashi, E., and Hassell, J. M. (2022) Great ape health watch: Enhancing surveillance for emerging infectious diseases in great apes. American Journal of Primatology, 84(4-5), e23379. Web.