Abstract

The following research proposal has been prompted by a series of surveys that were taken from a group of women at five state prison facilities located in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Georgia, and Mississippi. The purpose of this research is to study specifically the effects of being an older black female in prison today: how does prison life affect depression and anxiety levels, arid does a black woman’s socioeconomic background contribute to or hinder her ability to adapt to prison life? Also the effect that racial and cultural discrimination may have on black female inmates serving longer sentences and facing the possibly of dying in prison. The initial results of the surveys indicated a significant difference in depression, anxiety, somatization, prison adjustment, and death anxiety levels between White and Black female offenders.

Introduction

One of the most striking statistics in the American penal system is exponential expansion in prison population. From 300,000 prisoners in 1977, the prison population has risen steadily to over 1.5 million as of June 30, 2005, a 400% increase. By 2005, states were collectively spending over $43 billion per year on prisons. That this followed nearly fifty years of relative stability makes the growth all the more remarkable. (Pfaff, 2008) Julius Debro, an African-American scholar and leader in the field of criminal justice, found that another shift occurred in the year 1977. Prison populations shifted dramatically between 1967 and 1977 from having a white majority to a black majority. In addition to documenting racial discrimination, he asserted that covert racism in prison assumed many forms. For instance, whites were generally given more desirable work assignments, while blacks were given less desirable custodial assignments that limited their movement within the institution. (Ross & Hawkins, 1995) However, when it comes to women in prison there has been little research done as compared with that of men or the general population. There is however an alarming trend, the population of inmates overall that are 50+ years of age has been growing at a tremendous rate. This has been termed by some as the “Graying of American Prisons” (Abner, 2006) and has become both a social and financial crisis for prisons in general and has severely impacted the aging female population as well. This number is expected to top the quarter million mark by 2010.

Current research reveals that in general older women in prison have growing concerns about health, emotional stress, and social adaptation when trying to adjust to prison life. While at the moment women constitute a smaller portion of the overall prison population their numbers are increasing at a higher rate than that of their male counterparts. “On any given day, state and federal prisons in the United States hold more than 1,4 million inmates, of which roughly 101,179 are women” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2005, p. 32). In 1999, females represented roughly 10.8% of all populations according to A.J. Beck, while older offenders only accounted for 5% of this population, a disproportionate number of these women are African American. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation data, “women accounted for 20 percent of the increase in drug arrests between 1980-1989” (Greenhouse, 1991, p. 10). Older women reported a pervasive fear of abuse, from both fellow prisoners and staff.

In a comparison of women prisoners to their male counterparts, the increase in population size has almost doubled. In a national comparison of female prisoners, surveys show that female prisoners are “economically, politically, and socially marginalized” (Owen and Bloom, 1995, p. 165.). The lack of literature on female prisoners is not because of the fact that they do not commit crimes, but rather, social scientists choose to focus on their male counterparts instead when looking for the issues that involve prison inmates. Over the past 20 years the national female incarceration rate has more than doubled. Prison inmate size in 1990 was 44,000; the number in 2001 rose by more than 100% to 94,000. In spite of this large increase, the number of studies done on assessing adjustments in female inmates has been very limited. (Thompson and Loper, 2005, p. 715).

In a specific instance in the California correctional system older women prisoners are bunked eight inmates to a cell with only minimal consideration for an individual’s age, health status, or physical limitations. While many older women articulate the frustrations of overcrowding, noise, lack of privacy, and intergenerational tensions, they also reaffirm the importance of maintaining social relationships with younger prisoners. (Dignity Denied, 2006)

After these generalizations comes another factor that, by all prison rules and standards should not make a difference. Race and in particular inmates of African American heritage face these typical problems but it is being found that their treatment both before and after incarceration is markedly different from their white counterparts.

At midyear 2000, black women were incarcerated at a rate 6 times that of white women (or 380 per 100,000 U.S. residents versus 63 per 100,000 U.S. residents). By June 30, 2007, the incarceration rate for black women declined to 3.7 times that of white women (or 348 versus 95). An 8.4% decline in the incarceration rate for black women and a 51% increase in the rate for white women accounted for the overall decrease in the incarceration rate of black women relative to white women at midyear 2007. (Lawston, 2008, p. 5)

Lawston goes on to point out that in 2007, the incarceration rate of black women was 348 per 100,000 U.S. residents as compared to 146 Hispanic women and 95 white women per 100,000. black women tended to be incarcerated at higher rates than their Hispanic or White women counterparts across all age categories.

In the United States today, a black female is seven times more likely to be incarcerated than a white female- for similar criminal activity. While African-American females account for only thirteen percent of the American female population, they account for forty-four percent of America’s female inmate population. African-American women are more often denied bail and returned to prison for parole violation than are white females. (Lawston, 2008, p. 7)

These initial statistics also play a role in the treatment of black women in general but also affect the graying population of inmates as the age in a system that does not take their needs into full consideration.

Literature Review

In order to understand the scope of this issue this literature review will be divided into three sections, Female Inmates, Aging Inmates, and Black Female / Aging Inmates.

Feamle Inmates

The number of women in prison has dramatically increased over the past two decades. The increase could be attributed to the changing policies regarding drug crimes such as Truth-in-sentencing laws, mandatory minimums, and three-strikes-and-you’re-out rules established over the past several decades are keeping more offenders confined in prison for longer periods of time. (Sabol & Couture, 2008, p. 8) There have also been many socioeconomic changes that have created the increased need for women, especially mothers, to commit crimes.

There is also to be considered the marginal increase in the percentage of older adults in general as a result of baby boomers reaching late adulthood. Regardless of the reason, there has been a tremendous increase in long-term female incarceration and with that comes an increased concern about the health and welfare of this prison population.

In a comparison of women prisoners to their male counterparts, the increase in population size has almost doubled. In a national comparison of female prisoners, surveys show that female prisoners are “economically, politically, and socially marginalized” (Owen and Bloom, 1995, p. 165). The lack of literature on female prisoners is not because of the fact that they do not commit crimes, but rather, social scientists choose to focus on their male counterparts instead when looking for the issues that involve prison inmates. Over the past 20 years the national female incarceration rate has more than doubled. Prison inmate size in 1990 was 44,000; the number in 2001 rose by more than 100% to 94,000. In spite of this large increase, the number of studies done on assessing adjustments in female inmates has been very limited. (Thompson and Loper, 2005, p. 715).

While statistically, “men are 15 times more likely to be incarcerated than women, the rate of incarceration is growing the most for females at a 48% increase” (Aday, 2003, p. 59). This trend has been occurring for some time now as Chisney-Lind notes:

The rate of growth in female imprisonment also has outpaced that of men; since 1985 the annual rate of growth in the number of female inmates has averaged 11.1 percent, higher than the 7.6 percent average increase in male inmates. In 1996 alone, the number of females grew at a rate nearly double that of males (9.5 percent, compared to 4.8 percent for males). (Chesney-Lind, 1998, p. 66)

The author also re-confirms the fact that data regarding female inmates indicate that as cited the passage of increased penalties for drug offenses has certainly been a major factor in this increase. Again, it is also important to see that implementation of these stricter sentencing reform initiatives which supposedly were devoted to reducing class and race disparities in male sentencing, pay very little attention to gender and the particular needs of women have been grievously overlooked. (Chesney-Lind, 1998; Aday, 2003)

The advent of mandatory sentencing schemes and strict punishment for drug offenses has been devastating to women. Many states have adopted harsh mandatory sentencing schemes. The Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which eliminated gender and family responsibility as factors for consideration at the time of sentencing, were adopted. (5) The policy of eliminating gender and family responsibility, combined with heightened penalties for drug related violations, has caused the level of women’s incarceration to spiral upward. For the year 1999, 1 in 109 women were under correctional supervision. (6) In 1997, African American women had an incarceration rate of 200 per 100,000 compared to 25 per 100,000 for non-Hispanic white women. (Jacobs, 2004, p. 796)

A fundamental lack of research in the particular area of female inmates is another contributing factor to the minimizing of this sub-group of prisoners, as they seem to be classed. These special requirements of female inmates are often overlooked in part because of their lower population size in comparison to their male counterparts, which is of course fundamentally flawed reason. Most minorities are giving higher scrutiny, but this does not seem to be the case here. These special needs stem from the multitude of factors women may experience prior to incarceration that are often not shared in common with the male population of inmates. The fact that, “fifty-seven percent of female offenders experienced some form of physical or sexual abuse prior to incarceration, half were unemployed prior to arrest, and 64 percent failed to complete high school” (Aday, 2003, p. 172) certainly carries with it difficult coping needs. Furthermore, for these reasons, female offenders tend to have greater physical and mental healthcare needs (Aday, 2003; Dignity Denied, 2006). ) Females had higher rates of mental illness than their male counterparts with an estimated 73% females as compared to 50% males. Twenty-three percent of those females stated that they had been diagnosed with mental disorder by a mental health professional, this compared to 8% of their male counterparts. Mental health also seems to vary by race and age with 62% being white, 55% being black, and 52% were age 55 or older. Among women white females estimated 29% when compared to 20% of black females for mental illness. (Bureau Of Justice And Statistics, 2006, p. 4)

These women were less likely to have received regular visits from spouses, partners and children; were less satisfied with pre-release advice generally; and were less satisfied with advice about money and benefits. NACRO also stressed that this group of women may experience racial discrimination in employment and that their status as ex-offenders would add to the problems they faced. (McIvor, 2004, p. 168)

These factors mean a greater burden for the healthcare system in prison. Many female inmates feel they are receiving inadequate care, and certainly lack of gender specific care in many cases. Seventy-nine percent of offenders over age 65 report health concerns resulting in direct implications of the health management system in the correctional facilities. (Beckett, 2003, p. 14) Where there is a need for more intensified healthcare in the prison systems there is often very much less. “Women prisoners and older adult prisoners have needs which are distinct from other prisoners” (Watson, 2004, p. 119). For this reason, healthcare for these populations is becoming an increasing concern for correctional facilities.

Two thirds of women in all prisons are incarcerated for non-violent property or drug crimes. Bloom, Chesney-Lind, and Owen suggest that, …increasing numbers have suggested that their causes are lodged within larger shifts in the criminal justice system and its response to female patterns. The ill-named ‘war on drugs’ has become a war on women that has clearly contributed to the explosion in the women’s prison population (Bloom et al, 1994, p. 165).

Again, for numerous reasons, women inmates present with greater mental health issues, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted diseases, which display a different co-morbid pattern than that of their male counterparts. Prostitution, being abused as a child, running away from home, having illegal sources of income, and leaving education early, are all identified as leading causes as to the imprisonment of women.

Clearly, there is a link between mental illness, substance abuse and communicable diseases and this is of particular concern in the U.S. where women are the fastest growing population of prisoners (Watson, 2004, p. 124). The lack of alternative treatments for drugs, alcohol and increasing responses to crimes account for a majority of the increase in prison size, One study showed that women in prison use drugs more frequently and often use stronger drugs than men. Therefore, the drug rehab programs designed for men may not be applicable to women as they may face different challenges. (Watson, 2004, p. 124) This again is because women have different problems to deal with than men and consequently, different needs for coping. Another reason for women wanting to stay incarcerated is because although healthcare is not adequate inside, women in poverty cannot afford even the bare minimum in healthcare on the outside so the healthcare inside is at least better than none at all.

Although living in prison is difficult for all inmates, anecdotal evidence and a small number of qualitative studies on women’s prisons suggest that females have greater social support needs while incarcerated. This claim is important for a more complete understanding of adjustment to prisons. In particular, extra- and intrainstitutional social support mechanisms may reduce the inmate-perceived stresses associated with imprisonment and yield fewer official rule infractions” (Jiang, 2006, p. 32).

MacKenzie and Goodstien also found that “female inmates’ adjustment problems increased in proportion to the amount of time served, and concluded that long-term imprisonment was correlated with more situational problems related to the prison environment” (MacKenzie and Goodstein, 1985, p. 229). In 2001 Casey-Acevedo and Bakken also did a study on adjustment of incarcerated women. Their results indicated that long-term inmates committed higher rates of

violations and were more violent than short-term inmates do. They also reported that “inmates committed fewer offenses during the first and fourth quartiles than in the second and third, Researchers attributed this disciplinary pattern to anticipatory socialization. That is, inmates with impending release dates behaved better to improve their chances for release or parole” (Thompson and Loper, 2005p. 718). Older females both in and outside of institutions also report a greater sense of isolation and a lack of a support system when compared to men. Some studies have found that being involved with work related or social activities while incarcerated have had positive effects on adjustment to prison life. However, most studies have shown that prison adjustment is more strongly linked to education, race, and health status.

Aging (Graying) Inmates

Since there is a discrepancy among researchers about the definition of older inmates, there have also been discrepancies when trying to do comparative studies of older inmates. “The inability to agree on what constitutes an elderly offender is one of the most troublesome aspects of comparing research outcomes from various studies” (Aday. 2003p. 16). Reports in Canada and the U.S. have concluded that offenders over 50 are the fastest growing subgroup of inmates. (Beckett, 2003, p. 12) Although most general populations of prisons are very diverse, older offenders tend to fit into three categories according to May 1994. These are listed as follows: Long-term offenders, Repeat offenders, and First-time offenders. First-time offenders that are imprisoned late in life represent the largest group of the three categories. Other characteristics are that older inmates on average tend to look physically older in chronological age by anywhere from 10-12 years and the average 50 year old inmate is similar to a 60 year old non-inmate. However, this claim is said to be true more so of long-term offenders then first-time offenders. (Beckett, 2003, p. 14)

According to the U.S. Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. prison population has grown from just over 319,000 in 1980 to nearly 1.5 million in 2005. Elderly inmates represent the fastest growing segment of federal and state prisons. A 2004 report by the National Institute of Corrections states that the number of state and federal prisoners ages 50 and older rose 172.6 percent between 1992 and 2001, from nearly 42,000 to more than 113,000. Some estimates suggest that the elder prisoner population has grown by as much as 750 percent in the last two decades. (Abner, 2006, p. 9)

As previously mentioned, truth-in-sentencing laws, mandatory minimums, and three-strikes-and-you’re-out rules established over the past several decades are keeping more offenders confined in prison for longer periods of time (van Wormer & Bartollas, 2007; Yorston & Taylor, 2006). These laws have created a “stacking effect,” whereby older adult inmates have grown both in proportion and in number due to sentencing statutes that hold inmates long into their geriatric years (Kerbs, 2000b; U.S. Department of Justice, 2004). This trend has converged with the fact that, like other segments of the population, inmates are living longer. In addition, the number of older adults who are being prosecuted as first-time offenders is increasing. (Sabol & Couture, 2008, p. 8)

The individual mental health of prisoners also plays an important role in their ability to adjust to the prison environment. In 2005, it was reported that more than half of all prison and jail inmates had some form of mental health issue. (Bureau Of Justice And Statistics, 2006, p. 1) Jail inmates had the highest rate of mental disorders with a rate of 60%. While jails hold inmates for less than one year and state and federal prisons hold inmates for typically over one year, in general, prisons often provide a greater opportunity for inmates to receive mental health assessment and treatment. (Bureau Of Justice And Statistics, 2006, p. 3) The key to addressing mental health problems is menial health assessment. One report stated that 90% of prisoners had mental health issues with many also having substance abuse problems as a co-morbid condition. (Watson, 2004, p. 120) When compared to younger offenders, older offenders tend to experience high levels of’ social isolation, depression, and risk of’ suicide. These anxieties have shown to augment existing physical and mental health issues because the loss of social support is significant in that it is considered to be a coping factor for the effects of continuous stress. (Beckett, 2003, p. 15) Depression in particular has been noted to contribute to loss of functioning in everyday activities, the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, and increased risk of suicide. For older offenders, the fear of dying on the inside, not being able to care for themselves, or even the fear of coping on the outside if paroled, affect the severity of their depression. (Beckett, 2003, p. 16) Chronic pain, medical illness, or even lack of sleep can cause depression disturbances to name a few. In most studies to meet the criteria of depression or mental disorder, there are some distinct characteristics that the inmates report having. Some of these are, decreased interest in things that used to pleasure them, delusions or hallucinations, an increased sense of loss, and suffering from withdrawals. (Bureau of Justice And Statistics, 2006, p. 3)

According to early research done by Clemmer in 1958, and referenced in Flanagan’s study, long-term male prisoners experienced a steady deterioration in overall physical and psychological functioning over the course of their sentences. Recent research however contradicts these findings and states that, “long-term prisoners’ adjustment improves over the course of their sentences.” (Flanagan, 1992, p. 359). Furthermore, according to Flanagan’s research done in 1980, “Results indicated that long-term offenders did not experience psychological deterioration while incarcerated. On the contrary, long-term offenders who spent less than 3 years in prison reported more psychological problems and lower self-esteem than long-term offenders who had spent more than 6 years in prison. Flanagan attributed the short-term inmates’ disciplinary trend to initial anxiety and acclimatization to prison during the first quartile, and good behavior to expedite their releases by parole boards during the fourth quartile.” He also suggested that the consistent disciplinary trend with long-term inmates was due to age, lack of pre-release parole factors, and problem solving strategies. These strategies would help inmates solve conflicts with staff and other inmates in lieu of disciplinary actions (Thompson and Loper, 2005, p. 716). Results from Flanagan’s study showed that “over the course of their sentences, older inmates committed infractions at a more consistent rate than younger inmates. They also indicated that a significant decrease in long-term inmates’ reports of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and boredom when compared to the beginning of their prison terms” (Thompson and Loper, 2005, p. 717).

This graying of the prison population has also created a host of policy and practice issues that encompass justice considerations, cost-containment issues, and biopsychosocial care needs. The older prisoner’s physical, social, and psychological needs are complex and necessitate gerontologically based service delivery systems (Sabol & Couture, 2008, p. 8) Older inmates are a diverse group that might first be differentiated as geriatric and nongeriatric. Geriatric inmates include those with functional impairments who require assistance with activities of daily living (ADL) such as eating, bathing, or using the toilet; they are sometimes housed in separate units to accommodate their extensive long-term care needs. A second group of geriatric offenders is composed of inmates who need extra assistance but are not totally dependent. They may require environmental supports such as ramps and elevators that will aid in their mobility. Nongeriatric offenders are older adults who may have health ailments and other special needs but are still able to function independently; they are typically housed with the general population. (Sabol & Couture, 2008, p. 8)

The increases in population sizes have affected the delivery of the programs and services that they are provided, the staffing and security, crowding conditions, and medical care. “Chaiklin speculated that older inmates with mental illness are overlooked because of limited resources, cramped environments, and improperly trained staff’ (Lemieux~ et at, 2002, p. 447). It has also been said that older inmates have a higher risk for developing depression due to changes of health and age-related changes and losses. For some inmates prison may serve as a safer environment than the “outside” because it provides free meals, a bed, and free healthcare, For those who live in poverty this could be an actual upgrade in living conditions. According to a study of prisoners done in 2001 by Aday and Nation, “Rapidly declining health would force many to trade the prison environment for a nursing home bed, and most would probably choose a prison setting over the nursing home if the prison environment is sheltered.” Older inmates who come from lifestyles of poverty are often unaccustomed to the now readily available necessities of life (Aday, 2003,p. 117). Since poverty and lack of health care on the outside is so high, it has been reported, “some chronic offenders may also undergo some degree of institutionalization and find prison life to be more reassuring than life’s challenges. Numerous inmates have indicated that they have committed crimes in order to re-enter a prison setting offering such amenities as food, shelter, health care and a familiar way of life” (Aday, 2003, p. 60).

Many older inmates have little formal education, are in poor health, and commonly come to prison with few coping skills. “Zamble and Porporino (1988), as referenced in Aday, have suggested that inmates without previous prison experience cope better on the inside than those with prior experience” (Aday, 2003, p. 113). Some older inmates accept the fact that they deserve the punishment they received for the crimes they’ve committed and, therefore, are able to adjust more easily to the prison environment. Others adjust by looking at the advantages that prison life has brought to them late in life as stated by one prison inmate, “There is no rent here and no food bills” (Williams, 1989, p. 42). Abuse and dependency on drugs and alcohol has been found in 15 percent of older inmates, which could explain the high rates of anxieties and depression found in prison inmates. Theories suggest, “older adults drink in response to the material and emotional stresses associated with aging issues such as illness, bereavement, poverty, and social isolation” (Meyers, 1984, p. 53). Mandatory sentencing laws reduced the parolable inmate population in 1998 by 22 percent. These could definitely be reasons for increased anxieties among inmates and especially increased rates of death anxiety levels. Dying in prison is the most dreaded feeling of prisoners so most tend to try not to think about it. Usually those inmates with poorer health status reported higher death anxieties and expressed greater fears of vulnerability than those of healthier status, Older inmates in general are at higher risk for both mental and physical health issues. Whether these are caused from degeneration over time or are accelerated by circumstance, healthcare issues are still being neglected.

Dealing with these stresses, health problems, and anxieties affects how that person will adjust to their environment. As one would expect, the higher the stresses, the harder the adjustment. This is not always the case, as we will find in the research. Since stress affects people differently, some people can handle more stress than others. How we measure a person’s ability to adjust to their environment is by their responses to these stresses, their additional anxieties reported, and decreasing emotional health complaints that the prisoner may report.

Black / Female / Aging Inmates

In the 1990s, Blacks made up about 12 percent of the US population. On December 31, 2000, 46.2 percent of prisoners under state or federal jurisdiction were Black, up from 44.5 percent in 1990. Another 18 percent were Hispanic. In 1997 in the South, 63 percent of state prison inmates whose race was known were Black. 21 African Americans make up 63 percent of North Carolina’s prison population, 76 percent of its drug offenders and 92 percent of those imprisoned for selling and possessing schedule II narcotics. (Wood, 2003, p. 20)

Black women constitute a very diverse group. This ranges from low-income women to college educated professional women to Black lesbians to those in partnership with males, to Black women with HIV/AIDS or those in prison or the welfare system to those born in the United States as well as immigrants from abroad. Black women in particular have a long history of sexual violence in the United States. This stems from rape and forced breeding during slavery to demeaning stereotypes such as subordinate servant to sexually promiscuous activities. (Parker, 2004) Currently the numbers show that nearly half of the women in the nation’s prisons are 46 percent African American and 14.2 percent Hispanic. These data begin to hint at another important theme: The surge in women’s imprisonment, particularly in the area of drug offenses, has disproportionately hit women of color in the United States. Specifically, while the number of women in state prisons for drug sales has increased by 433 percent between 1986 and 1991, this increase is far steeper for African-American women at 828 percent and Hispanic women at 328 percent than it is for Caucasian women at only 241 percent. (Chesney-Lind, 1998, p. 79)

The following is an excerpt of on woman’s journey in the prison system as it is related to her narcotics addiction:

“I have done everything–prostitution, burglary, forgery, robbery and begging on the street to support my habit,” says CCWF inmate Beverly Henry, who at 51 has lived most of her life addicted to heroin and is now living with HIV and hepatitis C. “It’s overwhelming. That feeling is so overwhelming. It has so much control over you, it’s unbelievable.” (Davis, 2000, p. 162)

There are also racially biased perception that create stereotypical problems in prison, Black women, who are perceived as independent and unconventional, as defiant rather than fearful, with a succession of partners and with children in care, are most oftne held more blameworthy than white women who have committed similar offences. (McIvor, 2004, p. 193)

Consequently they are incarcerated at a higher rate than white women. According to Johnson, et.al., “ blacks appear to feel significantly safer in prison and have fewer symptoms of psychological distress than whites or 1-lispanics.” (Johnson, et at, 1976, p. 41)

It remains nevertheless a systemic construction essential to an understanding of the American penal system. Racial profiling, a “war on drugs” that targets African American neighborhoods and the drug dependencies of the poor, zero-tolerance urban policing and three strikes” legislation have created a prison system whose demographics are wildly at odds with the social profile of modern America. (Wood, 2003, p. 20)

Prison literature overall tends to support this theory. In 1990, the ACA did a survey of women inmates and found that “almost two thirds were earning $6.50 or less an hour” (Owen and Bloom 1995, p. 169), This could be clear evidence why women in poverty are more willing to commit criminal acts. Furthermore, according to Johnson, et al, “ blacks appear to feel significantly safer in prison and have fewer symptoms of psychological distress than whites or 1-lispanics.” (Johnson, et at, 1976, p. 41 ).

These Black women are prisoners, but the fact that they have been convicted of crimes often pales in comparison to the underlying causes and impact of their incarceration. For as surely as these “forgotten offenders” have been sentenced, they are suffering–and their plight is shocking. Experts say that while under the care of the correctional and judicial systems, Black women must cope with racism, drug addiction, sexual exploitation, motherhood and pregnancy, and a system that often is not set up with women in mind. (Davis, 2000, p. 162)

The number of Black women in prison increased 2.6 percent in 2006 according to the Department of Justice. Then once released from prison, studies have shown that most former inmates will return to prison and continue to fuel the socioeconomic cycle that includes single-parent homes. In fact, African-American children are nine times more likely to have a parent in prison, foster care and continue the cycle of generational poverty. (Henderson, 2007, 132)

…half of the 84,000 women confined in prisons at the local, state and federal levels were African-American. Today, there are more than 100,000 women in prisons across America. While nearly two-thirds of the women on probation or parole are White, nearly two-thirds of the women confined to prisons at all levels are minorities. (Davis, 2000, p. 162)

As predicted by many social activists the new mandatory arrest policies have had several negative results. They certainly have decrease the number of black women who would actually call the police for fear that they would be contributing to the already unbearable level of criminal justice intrusion into the lives of black men. These mandatory arrest policies have actually heightened the rate and severity of violence that women were experiencing. They could also lead to an increased number of black women being charged with domestic violence, since the police and the courts do not view black women as victims of domestic violence, but rather as mutual combatants in assault cases. (Jacobs, 2004, p. 799)

If the Black community is going to save itself, experts say, individuals and groups must become involved in changing America’s prison system and eliminating the conditions that manufacture Black prisoners–male and female. If the community doesn’t get involved, prison will continue to be a revolving door, says McGee of Hampton. “Those who are ultimately released are expected to become re-socialized into a society that often is not ready to support them,” (Davis, 2000, p. 162)

Their stories point to the exceedingly complex way in which environmental conditions reduce viable options that may help a woman avoid offending. The lack of access to resources cannot be undervalued. Donna Hubbard Spearman was arrested twenty-seven times. She states that no one counseled her about drug treatment or advised her of the availability of any program that she could attend to help her with her addiction. Mamie also talks about the lack of support available to her. (Jacobs, 2004, p. 807)

With black women the point at issue was the mother’s sexual lifestyle (Green 1991). These stereotype-led differences meant that for the white woman being a mother was likely to be a mitigating factor, whereas for a black woman it was used as proof of her fecklessness, and thus became an aggravating factor. (McIvor, 2004, p. 194)

There are also some other interesting and seemingly contradictory data concerning black women in prison. Reports on black female inmates indicate that long-term incarcerated women shared less concern about their safety than newly entering female offenders. MacKenzie (1989) suggested that, newly entering prisoners used play families as initial coping mechanisms, but needed them less as time passed. (Thompson and Loper 2005:718)

One of the most compelling examples of the success of diversity for inmates is seeing the presence of a diverse staff, particularly management staff. Correctional managers must practice what they preach by recruiting and retaining qualified staff that represent a wide variety of cultures and experiences. Again, while taking black and white into account is important, so are the contributions of females, older staff, employees from various ethnic backgrounds and those espousing different religions and beliefs. “We may not look alike on the surface,” notes Hiatt, “but inside we all live in the same way – By the beat of a heart.” (Wilkinson & Unwin, 1999, p. 103)

However, not all disparities are attributed to discriminatory attitudes among justice professionals.

In 1902, author H. C. Cooley coined the term “looking glass self,” referring to the idea that an individual’s self-perception is largely determined by the way others relate to him or her. This theory, when applied to racial and ethnic minority groups, suggests that if a community is treated as inferior or inhumane, that will subsequently affect how people within that community view themselves. (Morris, 2003, p. 93)

Methodology

The research was done using descriptive analysis of surveys that were given to a group of women at five state prison facilities. As stated earlier, the intent was to study the effects prison life has on older black females as far as depression, anxieties, and prison adjustment by examining self-reported data on these issues. The goal of this research is to gain a better understanding of how imprisonment affects the mental health of black females verses white females.

Participants

Participants were prisoners (N=325) aged 50 and over from five state prisons which consisted of 184 whites and 142 blacks; with the mean age of all participants from the 5 states being 55.4. Most of the women reported having graduated from high school and some reported having college education or a college degree. When comparing whites to blacks for education levels, whites had a higher education completion rate overall with a significant level of.022. When comparing other scales such as: depression scale, anxiety scale, prison adjustment, and death anxiety, these all showed a significant difference between whites and blacks as well. The participants were chosen by region and availability of participation.

Instrument

The research instrument was a structured questionnaire given to prisoners for self-reported data collection. The questionnaire contained several scales on prison adjustment, depression, anxiety, and death anxiety, all of which will be addressed in this paper. The questionnaire was broken down into a series of health questions about the participants health before and after entering prison. It analyzed their emotional and physical wellbeing while incarcerated, personal information about family and friends, if they visit or not, education levels, and other basics about who they are. These measures were then compared to see if there were any significant differences between the two races.

Measures

Prison Adjustment. As a measure of prison adjustment the researchers used a Liken type scale. The scale is similar to the one developed by Zainble and Porporino in 1988. This scale is found to have a Coefficient Alpha of.93. The scale asked respondents to rate factors of imprisonment as troubling them either “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” or “always.” Some questions asked were feelings of depression, loneliness, and irritability. Respondents who were troubled most frequently resulted in lower prison adjustment scores. When comparing white women and black women, prison adjustment scale was significantly different with a.007 on the 2-tailed t-test.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist

The Hopkins Symptom Checklist has been in use since the 1950’s and was originally developed by a team of researchers at John Hopkins University. It has been used to diagnose anxiety and depression the larger general population. A modified version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist was used to measure anxiety and depression because of the scales high internal consistencies, The scale asked respondents to rate their symptoms as “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, or “always.” Questions for this scale were about personal health before and after entering prison. However, it must be stated that there has been little adjustment to this test in regards to racial or cultural components.

In this study, depression was measured with a number of different factors including ten questions that addressed feelings of loneliness, hopelessness, and suicide. There were seven questions that addressed nervousness and elevation in heart rate. Eleven indicators including chest pains, muscle aches, and feelings of restlessness also measured anxieties,

Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale

The Templer death anxiety scale was developed in the 1970’s and has been used to determine a client’s reaction to death as it relates to their level of concern and anxiety. Here the Templer scale was administered with some changes and adjustments to focus on prison life. This test is a 15-item test that assists in determining the extent of an individual’s preoccupation with death and dying issues. This scale uses yes and no questions that focus on fears of the future or even dying in prison. Questions focused on feelings of fearing death, feelings of hopelessness and loss, and how frequently they thought about dying. However, again it must be noted that no racial or cultural biases were considered.

Data Collection

Researchers obtained permission to conduct the surveys by contacting the prison authorities at the states Department of Corrections, All participation was on a voluntary basis and all respondents were briefed on a description and purpose of the research. All respondents were also assured of their confidentiality rights and all respondents signed consent forms before participating in the research.

Data Analysis

I used a mixed method approach when analyzing the data to address all the issues involved with this research. Since this is secondary data, it is limited to examination of already recorded statements and does not allow for further probing questions for the research. When analyzing this data, I looked for patterns by utilizing the Pearson’s correlation analysis from SPSS. I also looked at any emotional trends or patterns that might emerge in the data to test anxiety levels within respondents.

Additionally, multiple regression and coefficient models were used to test the relationship between black and white women and prison adjustment. How women adjust to prison life, their anxieties, their stresses, and their depression levels can help us understand more about prison environment for older black females. Specifically, what their special needs are and if they are being met currently in our correctional facilities. My hope was to gain a better understanding of prison adjustment, depression, and anxieties caused by life in prison.

Results

Means

Means were obtained for all five scales and both independent variables, white and black female offenders. The mean for white offenders on the somatization scale was 19.47 and for black offenders were 17.13. The mean for white offenders on the anxiety scale was 13.54 and for blacks offenders were 10.63. The mean for white offenders on the depression scale was 21.48 and for the black offenders was 17.61.

The mean for white offenders on the death anxiety scale was 12.93 and for black offenders was 10.96. The mean for white offenders for the prison adjustment scale was 37.39 and for black offenders was 33.03. The differences in the means show a significant difference between white and black female offenders. This is important because it recognizes the specific needs for not only female offenders, but also for race specific offenders.

Table 1: Self-Reported Chronic Illnesses of Older Female Inmates by Race (Reported in %).

Bivariate Correlations

As indicated previously, I utilized Pearson correlation coefficients in order to identify the strengths associated between the variables. My Pearson correlation found a significance in all 5 scales, Depression scale was significant with a (r.008, p < 0.05), Anxiety scale was significant with a (r.004, p < 0.05), Somatization scale was significant at (r =.019, p <0.05), Prison Adjustment was significant at (r.003, pc 0.05), and Death Anxiety was significant at (r =.02 1, p~ 0.05).

Whites were almost twice the rate of Blacks for overall concern of health issues becoming worse for the following year. Abuse rates among the White offenders were also twice as high as the Black female offenders. Although White offenders feared further health issues getting worse in the future, Black offenders were the ones who reported having the highest rates of past addiction to drugs and alcohol with 61,3% compared to that of the White offenders who reported only 32.4%.

Cross-Tabulation Scales

The Cross-Tabulation scales were used to show the relationship between the Black and White female offenders, the results showed the significance between races as far as association when compared with the variables of Depression, Anxiety, Somatization, Prison Adjustment, and Death Anxiety while in prison. While some of the results did not show a huge difference between the two, the most significant differences were found in the Depression scale and the Anxiety scale.

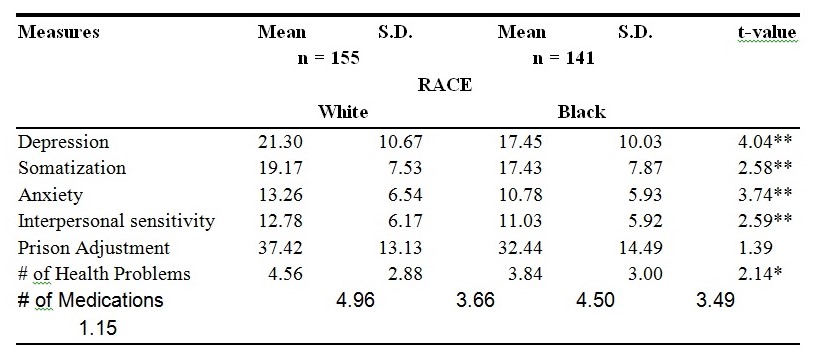

Table 2: Group Statistics.

T-Test Analysis

The t-test results show that for somatization, the mean score is 19 with a standard deviation being at 7 for the whole group. Among white the mean is 19 and blacks it is 17. The t-value is 2.58, which is above the significance level and therefore the results shows that for female inmates the incidence of somatization is significantly high. The incidence of depression among female inmates is also very high with a mean value of 21 and 10 standard deviation. Further the t-value of 4.04 indicating a significant effect of depression among female inmates. The black inmates have reported lower incidence of depression than white inmates have. The mean score of Incidence of anxiety among black inmates is 10 and that among whites is 13.26. This shows that there is a greater anxiety level among whites than black inmates.

The t-test value of anxiety was 3.74, which shows statically significant result indicating that female inmates have a higher level of anxiety. Interpersonal sensitivity among whites is higher than among black inmates and the result too is statically significant indicating a higher degree of interpersonal sensitivity among women inmates. Women inmates have significant problem of health as the t-test value of 2.14 which is significantly higher than 0. However, t-test values for prison adjustment and medications are not quite statically significant.

The results of the t-test do not support the results from Flanagan’s study, which indicate that “a significant decrease in long-term inmates’ reports of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and boredom when compared to the beginning of their prison terms” (Thompson and Loper, 2005, p. 717). The t-test result shows that depression among inmates is significant which has been supported by previous researches as that by Beckett (2003) and Bureau of Justice and Statistics (2006).

Table 3 presents the different variables, which has been studied as the effect on African American women in jail. In scale for depression, the African American women in jail reported to be less depressed than white women in jail, with a standard deviation almost same at 10. The t-value being 4 reveals that the results are statistically significant. This means that African American women in prison face less depression and their self-reported responses reveal that their depression level is moderately lower.

Table 3: Mean Differences in Mental/Health Measures by Race.

The problem of somatization among black women is lower than among white women. The study responses show that black women reported a mean somatization of 17.43 while that among white women is 19.17. The t-value is 2.58 revealing a significant result meaning that that the mean value shows statistically significant result. Thus, the problem of somatization among black women may be less than that among white women, but they form a significant effect on the mental health of the black women prisoners.

Anxiety among black women prisoners is less than that among white prisoners, mean score being 10 for the former and 13 for the latter. The t-value for the measure is 3.74 which is significantly greater than 1 indicating a statistically significant result. This indicates that women black prisoners are affected by high level of anxiety, which consequently affect their mental health.

Interpersonal sensitivity has a t-value of 2.59, which is significantly higher than 1 indicating a significant effect interpersonal sensitivity has on mental health of prisoners. The black prisoners have reported a mean score higher than that of white women prisoners indicating that black women prisoners are less affected by interpersonal sensitivity than white prisoners are.

Prison adjustment does not have a statistically significant result and therefore does not have a significant result on the mental health of black or white female prisoners.

Health problems availability also has a significant effect on the mental health of black prisoners whereas, while medication does not have significant effect on mental health of black prisoners in jail.

Limitations of the Study

While the findings of this report show some significant differences in the scales when comparing the white a black female prison population, it is important to remember that these findings are only taken from a sample of the Southern Region Women’s Facilities and does not represent a very widely based sample. While these are important findings, a more complete study should be followed up to compare these results.

Other limitations include, as have been mentioned, very little adjustments for racial or cultural bias. These have been mentioned in the literature review and my play an equally important factor when evaluating these results over larger populations. Also, as the literature indicates, having an awareness of the inmate initial mental condition prior to incarceration will play a major role in the she perceives her ability to cope with the aging process in prison as well as other psychosocial issues.

Discussion/Conclusion

This paper discussed the growing concern that female offenders have when it comes to adjusting to prison life. The fact that Black females enter the prison with a background that is already socio-economically different than their White counter part seems to be significant when it comes to future health issues in prison. The research has shown that Black female offenders show a significant increase in Depression and Death Anxiety scales. There were also differences found in prison adjustment and somatization scales. This could also be due to the socioeconomic status because the White female offenders had a harder time adjusting to prison than their Black counter parts. Typically because White offenders tend to be “let off’ for their offenses the first few times they offend and therefore only get put into jail after many times of being caught. Black offenders tend to get “punished” the first or second time and are more used to the system and therefore are able to adjust more quickly to their environment. They also usually come from families of offenders and are used to living in that lifestyle of prison or police.