Introduction

The climate change and environmental catastrophes it brings upon global society have been at the forefront of multiple scientific fields for the last several decades. Careless use of natural resources, fuel-linked contamination, and irresponsible waste management by businesses has led to grave environmental consequences. It is now generally accepted that a business can and should wield its financial power and resources to benefit the existing community with it exists in cooperation. This perception leads to the rise in responsible consumption, with customers paying increased attention to a firm’s environmental policies and sustainability status.

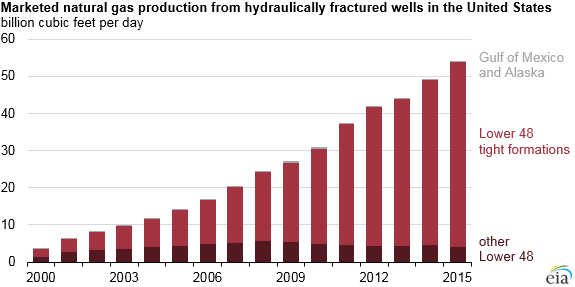

Consecutively, it is now both in the societal and financial interests of corporations to invest in sustainable resource applications and environment-oriented programs. The following paper addresses some of these international policies as applied by firms and governments, particularly in relation to renewable energy sources. The first section is dedicated to discussing the main outcomes and challenges of the Climate Change Conference of the Parties 2021. The second focuses on examining two life cycle assessments and potential fracking activities-related recommendations for Texas and the UK. The third section is centered on discussing the energy efficiency measures in housing and transport areas, specifically for Sweden, the UK, and China. And, finally, the fourth section evaluates the social, economic, and environmental benefits and costs of implementing renewable energy technologies in the United States. To illustrate the severity of some of the outlined consequences and challenges presented to the national environment, the following graph is presented, illustrating the growth rate of the US fracking industry.

Main Outcomes and Challenges of COP21

The Paris Climate Change Conference 2021 addressed the problem of the increased impact climate change has had on human lives internationally. The participants acknowledged the logical financing issue that comes from the need for the implementation of a variety of changes quickly. With one of the outcomes being the need to transition to a greener and more climate-conscious economy, the participants agreed that corporate billions had to be turned into a climate investment (Rhode, 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). Developing countries, in particular, were recognized as in need of support, and the conference participants re-established the agreement with developed countries to contribute 100 billion dollars to them. For comparison purposes, the committee identified that $78.9bn of climate finance was mobilized in 2018 (“A net-zero emissions economic recovery from COVID-19 -ORCA”, 2021). This sum includes the construction of new markets for mitigation and quality improvement, as well as developmental and educational programs on the climate issue.

England has been a prominent agent in the global efforts towards increasing the overall sustainability of multinational business. The United Kingdom doubled its financial commitment to the cause up to around £11.6 billion within the four years between 2021 and 2025 (Zierler et al., 2017). Thus, at the conference, they were in the position to encourage the other countries to undertake similar initiatives. Another main outcome of the conference included the agreement of the participants to strive towards net zero. The net-zero emissions approach refers to the commitment of countries and companies internationally to reduce carbon emissions to zero by the middle of the century. Naturally, this outcome of the conference is a challenge in itself.

When approaching the commitment to net-zero emissions, it is crucial that every financial decision is taken into account. This approach accounts not only for the private investment deals but also the spending decisions on national and international levels. To achieve the net-zero emissions program in the estimated period, companies need to remain consistent in their transparency in sustainability (Bataille, 2020; Pye et al., 2017). The individual stakeholders in the industry, such as insurers, investors, and other influential finance workers, need to commit to aligning their investment decisions with the climate change emergency requirements.

To encourage continuous evolution in the financial sector, the Climate Champions have established a sustainable financial alliance. After its launch, the project already includes more than 160 companies that, in combination, have access to assets of US$70 trillion (Bradshaw & Waite, 2017). The participants of the alliance re-established their commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 at the latest. Another emerging challenge involves the requirement of these initiatives to be accredited by the Race to Zero, as in using the science-based research standards to dissect them for further analysis (Bradshaw & Waite, 2017). Currently, the coalition involves 43 banks holding $28.5 trillion, 87 asset managers representing $37 trillion, and 37 asset owners representing $5.7trillion (Wang et al., 2020). The current outcome of the conference involves the continuous expansion of this project by recruiting new potential alliance members. The potential challenge emerging from this involves internal management problems and potential opportunities for corruption and fraud.

Another key result of the conference may be summed up as increased attention to the negotiation tactics on climate issues, as summarized in the Paris Rulebook. To enable greater sustainability ambitions that would benefit the Net Zero goal, it is important to develop mutually beneficial trade-offs between companies and society (COP21, 2021). Any United Nations negotiations are based on consensus and mutual respect, with the voice of every participant being both heard and accounted for at the decision-making stage (COP21, 2021). Thus, the committee is motivated to address the diversity and representation issue going forward by paying attention to their speakers’ national and cultural identities.

Overall, the conference attendees are understandably concerned about how their efforts in acquiring greater finances, promoting accountability, and improving diversity will impact the progress with the net zero. A multi-level collaboration is required between society, businesses, and volunteer organizations to improve the overall environmental situation and manage the existing resources more wisely (“UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC – Glasgow 2021”, 2021). The emergence of new alliance-focused organizations, such as the financial coalition mentioned above, might be the way forward in structuring and optimizing the climate effort.

Fracking Activities Recommendations

Texas

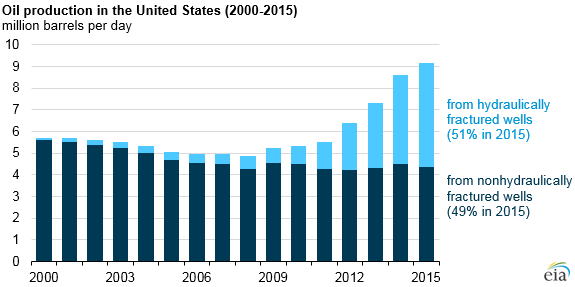

Fracking is also known by ecologists as hydraulic fracturing, and it refers to a common method of gas and oil extraction. During fracking, a fluid is injected into the rock formations at high pressure, and this way of natural resource extraction is reasonably common in America (Clough, 2018). As of 2020, Texas is stated to be a leading state nationwide in terms of the production of natural gas, the vast majority of which is sourced through fracking (EIA, 2021). In 2000, around 23 thousand hydraulically fractured wells, with the number rising up to 300 thousand by 2015. The latter figure accounted for over 67 percent of the US gas production and over 50 percent of the US oil production (EIA, 2021). By logical extension, it is reasonable to assume that the current state of these industries is threatening environmental stability. The graph below indicates the share of hydraulic fracturing in the national production of oil as of 2015/2016.

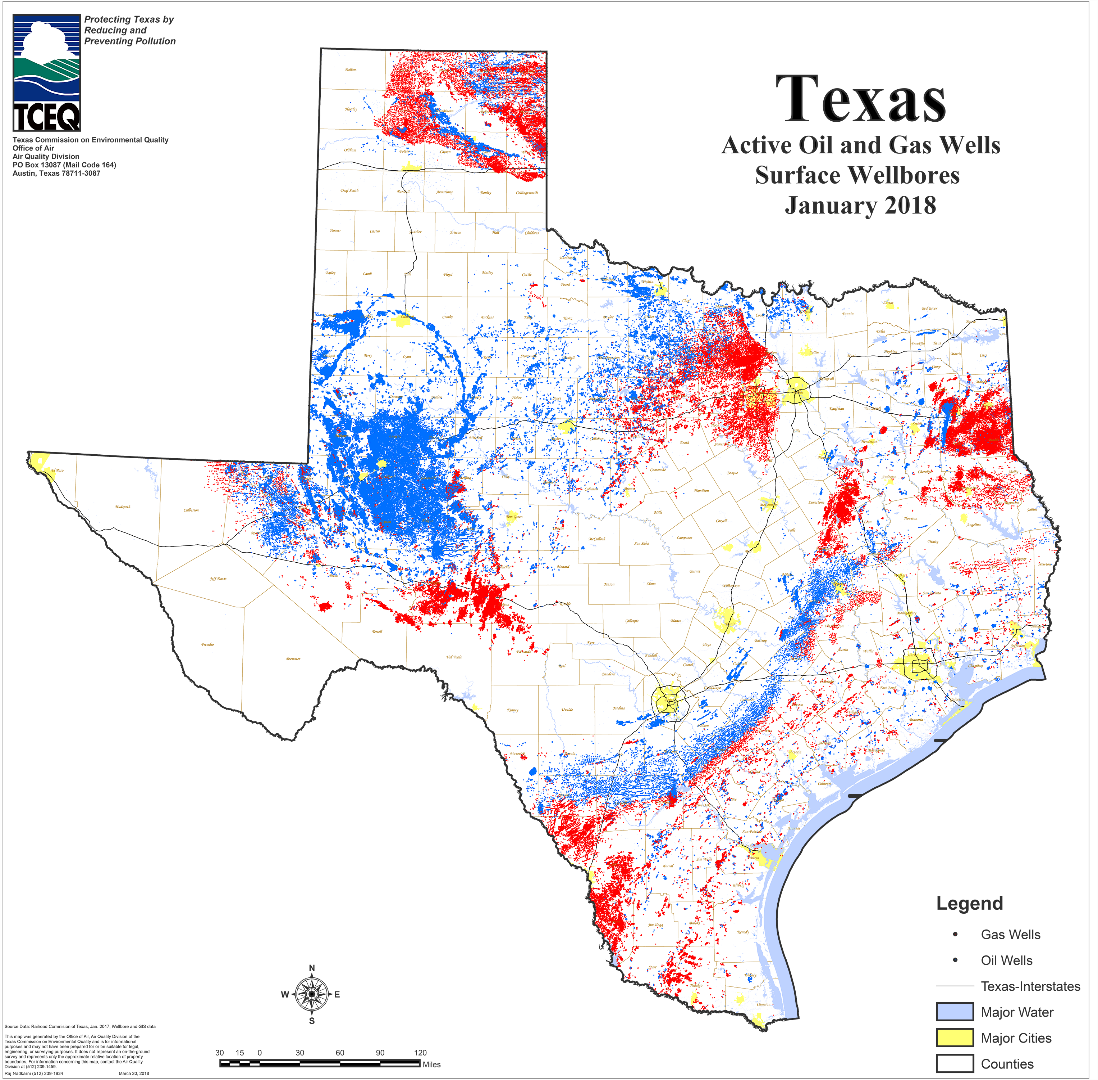

The main Texas deposits include the Palo Duro Basin, Anadarko Basin, the Barnett Shale, the Eagle Ford Shale, and the Haynesville-Bossier Shale and the Permian Basin. Throughout the first half of 2017, Texas possessed 279,615 active oil and gas wells. However, by May January 2018, the number of open wells fractured and reduced significantly, indicating the shift in the public perception, environmental development and investment policies.

With fracking going back in Texas for as long as the 1800s, it has affected the environmental and commercial landscape of the state substantially (Short & Szolucha, 2019). To provide an overview of the fracking activities in Texas, as well as the established legislative policies and extraction procedures, a case study on the Eagle Ford Shale was chosen. As the industry began to skyrocket, experiencing an energy boom in the first half of the 2000s, gas prices went up, increasing its attractiveness. (Wenzel, 2012). Currently, the water supply of the Eagle Ford region is endangered by fracking poisoning and the expanding population, expected to grow by a further 175% by 250.

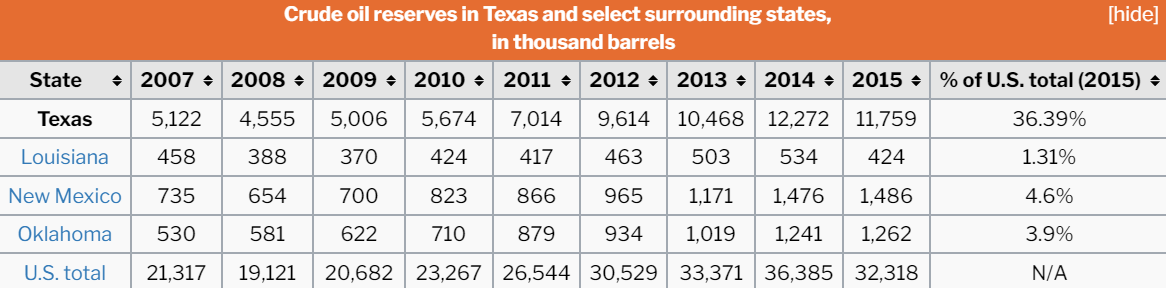

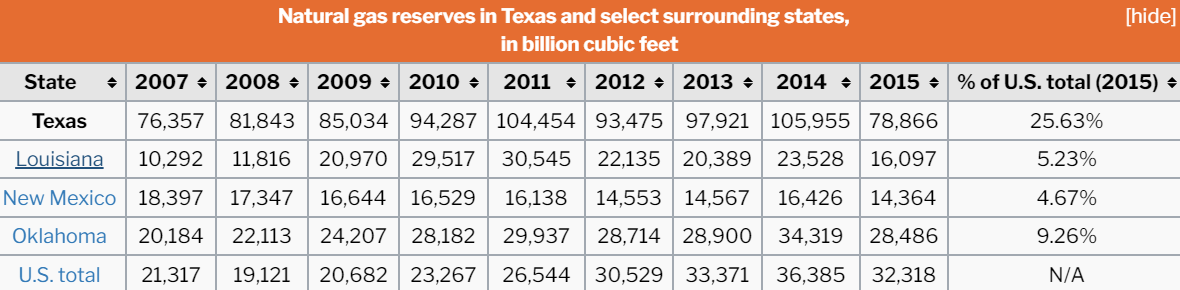

By March 2017, the state of Texas demanded that all the companies who were engaging in the fracking present a list of chemicals they were using in the process. The tables below present the established crude oil and natural gas reserves in Texas and surrounding areas between 2007 and 2015 and were sourced from the Energy Information Administration – EIA (Brantley et al., 2018). In this context, the proven sources for Texas means “estimated volumes of hydrocarbon resources that analysis of geologic and engineering data demonstrates with reasonable certainty are recoverable under existing economic and operating conditions.” (EIA, 13). The estimates for the numeric data concerning the number of resources might not be fully representative of the reality. It is therefore important that Texas residents and authorities interpret it further with their cultural context.

In recent years Texas had seismic activity many have linked to the fracking activity prevalent in the state, with critics calling for the restriction of the potentially dangerous activities. In late April and early May of 2018, three earthquakes occurred within the span of one week. Their difficulty ranged from 2.7 to 3.4, which is significant considering the region was not considered seismically active before. Another eighteen earthquakes were reported across the state during the past three years. It is still unclear whether the activity was directly caused by fracking, with the Texas Railroad Commission tasked with investigating the matter further (Maniloff & Mastromonaco, 2017). It is important to specify that in the public eye, fracking is responsible for this tendency, which creates additional pressure towards the state authorities to restrict it further.

Furthermore, in Autumn 2016, the Texas authorities established a regulation that introduced a set of significantly more lenient requirements for plugging inactive wells. The new rule required the wells to produce a greatly reduced minimum amount of output to classify as active (Savitski & Nuryyev, 2018; Meng, 2017). It was now sufficient for a well to produce at least one barrel of oil or 1,000 cubic feet of gas per month for a year. Alternatively, the wells could produce at least five barrels of oil or 50,000 cubic feet of gas per month within the span of three consecutive months.

United Kingdom

Currently, the UK centers its oil production in the south of the country, while its gas extraction is allocated to the north. The biggest active shale in the north of England contains, on average, 1,300 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Howell, 2018). For comparison, the United Kingdom’s energy requirements are as low as 3 trillion. It is fair to specify, however, that only a small percentage, between 4 and 5, of natural gas in the shale can be extracted.

When a conversation around the U.K. fracking industry emerges, it more often than not focuses on the procedures, policies and regulations concerning Shale Gas. The particular case study, Shale gas extraction in the UK: a review of hydraulic fracturing, was selected for a detailed review to provide an outlook on fracking and its consequences (Watterson & Dinan, 2017). Conducted by the Royal Society in the Royal Academy of Engineering in 2012, it comments on a variety of relevant topics, including the fracking mechanisms, associated legal procedures and environmental damage reduction tactics. The case study operates under the assumption that fracking can be carried out in a safe manner, provided all the necessary regulations are followed (Watterson & Dinan, 2017). The main nationwide issue with the observation, however, lies in the lack of detailed expertise in the fracking field across research. Consecutively, the British scientific community is unclear on its ability to assess the measures and their enforcement procedures appropriately. The case study calls for a grounded approach to risk assessment and flexible guidelines rooted in the balance between commercial and environmental interests.

Potential damaging consequences discussed by the policymakers in the U.K. include negative health implications and concerns about the life expectancy impact. As of now, the companies that plan to undertake a fracking mission are obliged to notify the Health Chief Executive at least three weeks in advance (White et al., 2015). The design and step-by-step breakdown of the operation are to be provided with the notification to ensure the drilling is compliant with current regulations.

Recently, the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) report indicated that both the pricing of natural gas and the country’s reliance on it for fuel purposes remained the same. Furthermore, it argued against fracking’s economic efficiency based on the internal ties within the energy market in Europe (Brock, 2020). Domestically produced gas, however, will reduce reliance on imports from overseas. Assuming fugitive emissions are kept under control, it can also have a lower carbon footprint than the alternatives transported internationally through the sea.

Cuadrilla’s current proposition indicates that all the fracking operations at the assigned district are finalized within 30 months from the date of their beginning in 2019. The energy firm has requested an 18-month extension from the city council, which has not yet been granted as the company is currently being investigated for its potential leaks to seismic anomalies (Bradshaw & Waite, 2017). Cuadrilla’s proposal, however, was later rejected for the newer mines in the region due to its high logistical cost and ties to traffic complications. Interestingly, the later fracking activities propositions were rejected on the basis of infrastructural clashes rather than the negative ecological impact.

A Comparative Analysis

When examined in close proximity, the fracking histories of Texas and the UK possess a range of similarities and differences alike. Both cases indicate the prolongated presence of the fracking industry for fuel sourcing purposes within the respective economies. As demonstrated in other sections of this paper, both areas rely heavily on natural gas and oil as their primary energy sources. Despite the worldwide focus on sustainability, the energy industry is slow to transform due to the high barriers to entry in the renewable energy field and the financial interests of the gas and oil companies. Thus, it is evident that both Texas and UK rely on fracking activities in sourcing fuel while having to navigate their environmental consequences.

The differences between the two areas’ fracking profiles mainly focus on the policy framework and public perception of the activity within the region. The United Kingdom prioritizes the level-headed and step-by-step approach to fracking activity restrictions. Government officials, activists and companies themselves are urged to assess risk carefully without overexaggerating it. The environmental damage of fracking is discussed in the United Kingdom less than in Texas, where the conversation is dominated by the harm reduction and alternative solutions narratives. As Texas navigates the long-term fracking effects on its soil structure, biological diversity and, most importantly, water supply, it acts in the active search for alternative energy sources.

Energy Efficiency Measures in Housing and Transport

Sweden

Energy and carbon dioxide taxes are potent tools for energy efficiency in Sweden which strongly intensify companies to seek out green alternatives. Other policy instruments, such as technology procurement groups, assist the existing taxation legislation, enforcing them with greater efficiency. This refers to when a group of people buys new technology together in order to exert downward pressure on prices (Bhadbhade et al., 2020). There are three of them currently damaging the existing properties in the construction landscape. One is for landlords of commercial buildings, one is for landlords of residential structures, and one is for home builders. Furthermore, Sweden’s construction code has included energy efficiency criteria since the 1950s, with appropriate revisions introduced at least once every ten years (Muhoza & Johnson, 2018). Each time the building code is changed, it applies to more buildings, which must meet greater energy efficiency criteria.

Between 2000 and 2018, transportation consumption in the country increased by a total of 6%. The mode split has remained remarkably stable, with road transport accounting for 92 percent of all travel. Between 2000 and 2018, the percentage of people who drive a car declined from 84.2 percent to 81.5 percent. Meanwhile, the percentage of people who use public transportation has decreased from 7.5 percent to 7 percent (Bhadbhade et al., 2020). Taxes on energy and carbon dioxide are the most important policy instruments in the transportation sector. Aside from that, there is a slew of particular policy tools (such as a bonus-malus system for private vehicles or support for electric cars).

United Kingdom

Historically, Britain is known for severe construction regulations and compliance with the Supplier Obligations EU Production Standard Act. These mechanisms together allow it to deliver impressive results in building energy use regulation. Even the non-domestic buildings have been successfully controlled by governmental regulations since the 1970-s. (Nolden & Sorrell, 2016; Muncie, 2017). The Energy Efficiency Obligation policy was first introduced in 1994, requiring domestic energy suppliers to ensure buildings are equipped with compatible energy efficiency measures. This initiative was dedicated to installing new energy-controlling technology in each UK private home by 2020.

Increasing the efficiency of household energy use will be a crucial aspect of the British government’s financial recovery policy following the coronavirus outbreak. The Green Homes Grant has introduced a £2 billion initiative that allows homeowners and local government institutions to access the relief funds. Currently, the Grant operates a training program that intends to aid the fund by raising the quality and accessibility of training for the skills required to adapt homes (Qu et al., 2020). The UK’s current energy efficiency measures are mostly based on the 2016 Building Regulations with little adjustment. Extensions, conversions, building envelope renovations, and boiler and window replacements are equally subject to building requirements. Under these guidelines, the new buildings must fulfill minimum thermal transmittance criteria to avoid fine assignment. When additions are planned with criteria for new heating systems, existing buildings must satisfy similar standards.

Cars consumed 58 percent of the energy used in the UK transportation industry in 2018. Road freight transport (trucks/light vehicles) has the second-largest energy use in the transportation sector (32 percent). Buses (2.7 percent), rail (2.6 percent), water (2.3 percent), air (1.6 percent), and motorcycles account for the remaining energy use (0.5 percent) (Malinauskaite et al., 2019). Private cars dominated passenger traffic in 2018, accounting for 85 percent of passenger kilometers (87 percent in 2000). From 12.8 percent in 2000 to 14.7 percent in 2018, public transportation’s proportion of overall traffic increased by two points.

A variety of national policies aimed at enhancing energy efficiency in the transportation sector complement EU vehicle emission performance regulations. Support for the expanding ultra-low emission vehicle market has been prioritized. To specify, the grants are provided to customers to encourage and facilitate the domestic purchases of self-sufficient charging points. The initiative includes the Grant for plug-in cars, the Grant for plug-in vans, a workplace charging scheme, an electric vehicle-oriented domestic charge scheme, and an on-street charging point scheme (Hermans et al., 2018). Furthermore, le the Vehicle Excise Duty, corporate automobile tax regulations, and increased money allowances have encouraged LEVs and assisted the infrastructure improvement.

The Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation Act is adequate legislation in the area of energy efficiency as of now. The Renewable Transport Gasoline Obligation requires fuel companies to supply a particular biofuel volume or pay a relief package worth of funding. Only the companies whose output is over 450,000 litters of road transport or machinery fuel within the British production in a focus year are eligible and required to comply. The Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation experienced a substantial increase by five percent in volume throughout the year 2020, with a further increase up to 12.4% expected by 2032.

China

As of 2017, buildings and construction initiatives were consuming 18.35% of the country’s total demand for energy. The growth rate of energy consumption by buildings has been steadily decreasing over the last few years, going down from 11.9% at the 10th FYP to 6% at the 11th/12th FYPs (Li & Lin, 2018; Zierler et al., 2017; Borozan, 2018). Hence one can assume the policy changes implemented by the government have been successful. The country primarily relies on outcome-focused policies, innovating construction and design practices alike to maintain the building energy construction as low as possible.

China is successful in establishing ‘green buildings,’ which from the get-go adopts a holistic approach to environmental commitment and energy efficiency in the construction industry. The implementation of China’s Green Building Development Strategy requires better industry-level guidance on the development of ultra-low energy buildings (Xin-gang et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). To achieve that, the Passive Ultra-Low Energy Green Building Technical Guidelines on Residential Buildings were established in 2015 and quickly adopted by the local construction firms (Hansen, 2018). The same body later issued the 13th edition of Building Energy Conservation and Green Building Development mandate in 2017. The ambition was to increase the proportion of urban green building areas in the total area of new buildings to 50% by 2020 (Zhu et al., 2019). Considering the high population density within the country, it results in the ambitious goals of introducing over 10 trillion square meters of green buildings by 2030.

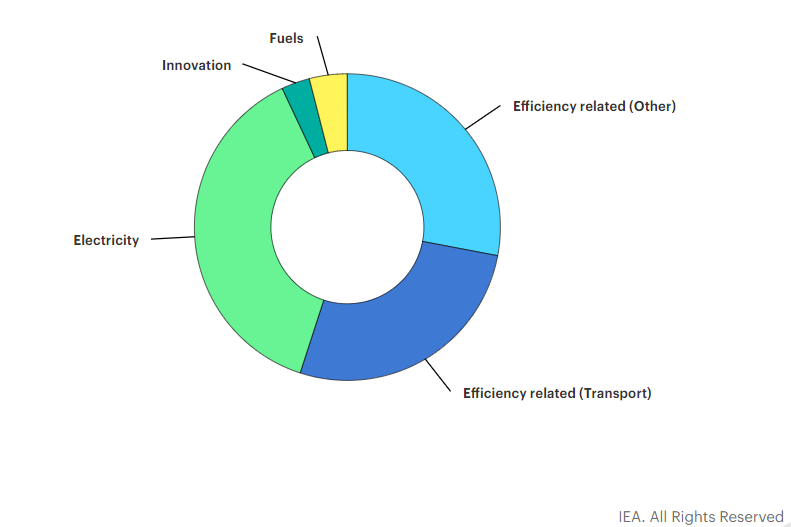

China is making strong progress in designing and establishing a clean transportation policy with falling energy costs on individual and corporate levels alike. In recent years, the industry’s focus has shifted to energy conservation and carbon emissions reduction, recognizing transportation’s role in environmental contamination. Energy efficiency improvements in the transport sector are primarily driven by energy security concerns and emissions reduction requirements for CO2 and other pollutants damaging to health and the general environment. Currently, the energy consumption reduction policies are implemented within the Sustainable Recovery Plan, which focuses on the rebuilding of the Chinese economy after the COVID-19 crisis. The graph below showcases the proportion of energy-related spending that has been allocated to energy efficiency initiatives in 2020 and 2021. By 2022 the country aims to reduce the carbon emissions percentage in the transport sector by another 8 percent.

A separate set of standards for fuel economy in China was designed for light-duty vehicles in 2004 and became more restrictive over time. The current set of rules requires a fuel consumption of 51 per one hundred kilometers, amounting to around 120 grams per kilometer per passenger (Xiong et al., 2019). It is safe to assume that the restrictions might continue to tighten if necessary. Heavy-duty vehicles are subjected to even stricter governmental demands, with the appropriate legislation updated yearly.

Renewable Energy Technologies in the US: Social, Financial and Environmental Impacts

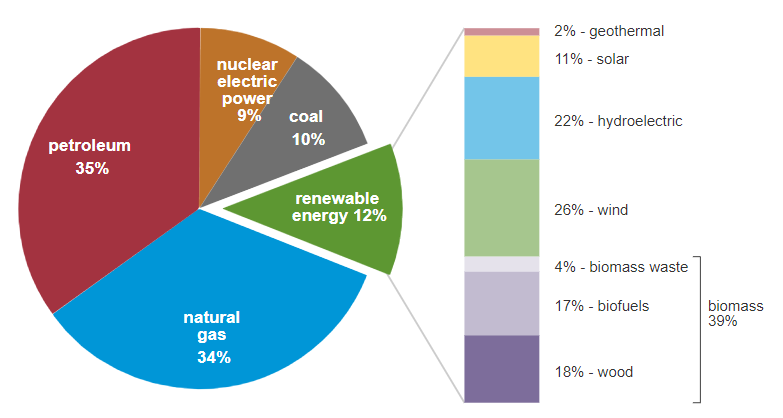

The U.S. is an international production and service industry leader, with the other side of the coin resulting in the country’s enormous energy requirement. As one can see from the diagram below, in 2020, almost 70% of the American energy consumption is constituted of petrol & oil products and natural gas. However, it is reasonable to claim that the United States would benefit from the shift of paradigm towards renewable energy sources on multiple levels, including social, economic, and environmental.

Social

The social benefits of shifting towards renewable energy use are numerous, as the current relationship between the gas and oil companies and society has been recognized as unhealthy. The change of paradigm would indirectly result in reduced inequality, greater levels of average health and life expectancy, and general life satisfaction. From a political standpoint, these notions are crucial for governments when considering their policies in relation to an issue. Furthermore, with a direct connection in place between the reduction in emission levels and the introduction of renewable energy sources, the approach’s environmental benefits are undeniable. Thus, it is tied with all the social benefits of a better relationship with the natural environment.

Financial

From the economic point of view, it was discovered that renewable energy sources benefit the community in a variety of unexpected ways. Traditional energy sources, although profitable, lead to the economic over-reliance on raw materials extraction. In many cases, it results in the emphasis on outdated, pre-industrial business practices, with extraction-based economies, such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, being dominated by oil and natural gas industries. As renewable energy sources are at the forefront of scientific innovation, investing in them indirectly contributes to the development of a profitable advanced infrastructure.

Renewable energy sources are typically expensive at the initial stage of the research and development of the project and the establishment of new facilities. It has been noted that notorious and multi-level savings are possible. Renewable energy completely revolutionizes consumers and businesses’ relationship with their natural environment (Upstill & Hall, 2018). It shifts the focus of the employment and production opportunities associated with the energy sector towards a more consistent and less damaging source. The range of jobs ranging from high-tech manufacturing to maintenance in the energy sector is growing consistently, caused by both the novelty of the field and the sphere’s talent requirements.

Additionally, the taxes paid by the renewable energy companies would benefit the economy of the United States, infusing the areas that need additional financial support. Ultimately, any introduction of a new corporate-intense field reduces the burden on the individual taxpayer, potentially resulting in tax cuts and increasing individual purchasing power (Tan-Soo et al., 2018). Finally, after the project establishment stage, renewable energy is a comparatively inexpensive resource due to the lack of scarcity. This leads to the reduction of corporate energy bills, with spare funds being now available for reinvestment into further business or community development. For companies in general renewable energy presents a massive opportunity in the sustainability management field, reducing production waste and

Environmental

Renewable energy initiatives contribute to the overall improvement of the ecological situation by reducing carbon emissions volume. The existing research established little to no impact on the lifestyle of the residents in a particular area, tourism, energy supply costs, and impacts on education. However, the introduction of renewable energy sources improved the life standard on the societal level, and facilitated the establishment of the social bond and community development (Akorede et al., 2010). The benefits in question come with caveats of the renewable energy projects often being condition-sensitive and expensive to install. The preparations and execution demand unusual attention to detail, particularly when applied to international efforts.

The main aspects of the environmental damage associated with non-renewable energy include water and air pollution. Water pollution, in particular, is tied to waste management, with energy products-related waste, such as oil remains, being some of the most toxic substances there are. Therefore, by introducing and popularizing renewable energy sources, it is comparatively easy to decrease water pollution levels. Looking back at Texas’ concerns regarding the long-term future of its water supply, certain states are in urgent need of diversifying their energy sources and shifting towards sustainable alternatives. With one of the biggest and most productive economies in the world, the U.S. would benefit massively from increasing its use of renewable energy sources. The potential ecological benefits of such change range from production-related pollution decrease to re-imagination of the role business plays in climate change and its response policies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the four sections of the paper indicate the shift in paradigm towards a greater level of industrial accountability. With restrictions on gas and oil production and extraction tightening worldwide, many energy corporations look to diversify their investment portfolio by branching out into renewable sources. The action, however, needs to be universal and with an emphasis on the corporate and governmental, rather than individual effect. This is why climate change-oriented conferences, such as COP21 and new legislation introduced, are vital in informing and popularizing some of the anti-climate change measures. Renewable energy is one of the greatest tools in society’s united front against climate hazards, as it provides a safe alternative while satisfying the needs of economies and individuals. It is therefore important that the sphere continues to develop, steadily increasing its percentage in a country’s energy consumption statistics.

References

Akorede, M., Hizam, H., & Pouresmaeil, E. (2010). Distributed energy resources and benefits to the environment.Renewable And Sustainable Energy Reviews, 14(2), 724-734. Web.

A net-zero emissions economic recovery from COVID-19 -ORCA. Orca.cardiff.ac.uk. (2021). Web.

Barnett Shale Maps and Charts. Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. (2021). Web.

Bataille, C. Physical and policy pathways to net-zero emissions industry. WIREs Clim Change. 2020; 11:e633. Web.

Bhadbhade, N., Yilmaz, S., Zuberi, J., Eichhammer, W., & Patel, M. The evolution of energy efficiency in Switzerland in the period 2000–2016.Energy, 191, 116526. Web.

Borozan, D. (2018). The technical and total factor energy efficiency of European regions: A two-stage approach.Energy, 152, 521-532. Web.

Bradshaw, M. & Waite, C. (2017), Learning from Lancashire: exploring the contours of the shale gas conflict in England Glob. Environ. Change 47 28–36.

Brantley, S., Vidic, R., Brasier, K., Yoxtheimer, D., Pollak, J., Wilderman, C., & Wen, T. (2018). Engaging over data on fracking and water quality. Science, 359(6374), 395-397. Web.

Brock, A. (2020). ‘Frack off’: Towards an anarchist political ecology critique of corporate and state responses to anti-fracking resistance in the UK.Political Geography, 82, 102246. Web.

Clough, E. (2018). Environmental justice and fracking: A review.Current Opinion In Environmental Science & Health, 3, 14-18. Web.

COP21. (2021). COP21: Results and Implications for Pathways and Policies for Low Emissions European Societies. Glasgow: United Nations.

Eia.gov. (2021). Web.

Hansen, A. (2018). Heating homes: Understanding the impact of prices. Energy Policy, 121, 138-151. Web.

Hermans, M., Bruninx, K., Vitiello, S., Spisto, A., & Delarue, E. (2018). Analysis on the interaction between short-term operating reserves and adequacy. Energy Policy, 121, 112-123. Web.

Howell, R. (2018). UK public beliefs about fracking and effects of knowledge on beliefs and support: A problem for shale gas policy.Energy Policy, 113, 721-730. Web.

Hydraulically fractured wells provide two-thirds of US natural gas production. Eia.gov. (2017). Web.

Lee, J. (2021). Greater energy efficiency could double China’s economy sustainably – Analysis – IEA. IEA. Web.

Li, K., & Lin, B. (2018). How to promote energy efficiency through technological progress in China?.Energy, 143, 812-821. Web.

Malinauskaite, J., Jouhara, H., Ahmad, L., Milani, M., Montorsi, L., & Venturelli, M. (2019). Energy efficiency in industry: EU and national policies in Italy and the UK.Energy, 172, 255-269. Web.

Maniloff, P., & Mastromonaco, R. (2017). The local employment impacts of fracking: A national study. Resource And Energy Economics, 49, 62-85. Web.

Meng, Q. (2017). The impacts of fracking on the environment: A total environmental study paradigm.Science Of The Total Environment, 580, 953-957. Web.

Muhoza, C., & Johnson, O. (2018). Exploring household energy transitions in rural Zambia from the user perspective.Energy Policy, 121, 25-34. Web.

Muncie, E. (2019). ‘Peaceful protesters’ and ‘dangerous criminals’: the framing and reframing of anti-fracking activists in the UK. Social Movement Studies, 19(4), 464-481. Web.

Nolden, C., & Sorrell, S. (2016). The UK market for energy service contracts in 2014–2015.Energy Efficiency, 9(6), 1405-1420. Web.

Pan, X., Guo, S., Han, C., Wang, M., Song, J., & Liao, X. (2020). Influence of FDI quality on energy efficiency in China based on seemingly unrelated regression method.Energy, 192, 116463. Web.

Pye, S., Li, F., Price, J. et al. Achieving net-zero emissions through the reframing of UK national targets in the post-Paris Agreement era. Nat Energy 2, 17024 (2017). Web.

Qu, C., Shao, J., & Shi, Z. (2020). Does financial agglomeration promote the increase of energy efficiency in China?. Energy Policy, 146, 111810. Web.

The Railroad Commission of Texas. Rrc.texas.gov. (2021). Web.

Rhodes, C. (2016). The 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference: Cop21. Science Progress, 99(1), 97-104. Web.

Rosenow, J., Guertler, P., Sorrell, S., & Eyre, N. (2018). The remaining potential for energy savings in UK households. Energy Policy, 121, 542-552. Web.

Savitski, D., & Nuryyev, G. (2018). Enhancing electric reliability with storage-field generators. Energy Policy, 121, 611-620. Web.

Short, D., & Szolucha, A. (2019). Fracking Lancashire: The planning process, social harm and collective trauma. Geoforum, 98, 264-276. Web.

Tan-Soo, J., Qin, P., & Zhang, X. (2018). Power stations emissions externalities from avoidance behaviors towards air pollution: Evidence from Beijing. Energy Policy, 121, 336-345. Web.

UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC – Glasgow 2021. UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC – Glasgow 2021. Web.

Upstill, G., & Hall, P. (2018). Estimating the learning rate of technology with multiple variants: The case of carbon storage. Energy Policy, 121, 498-505. Web.

Wang, X., Yu, Y., & Lin, L. (2020). Tweeting the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21): An analysis of a social network and factors determining the network influence. Online Social Networks And Media, 15, 100059. Web.

Watterson, A., & Dinan, W. (2017). The U.K.’s “Dash for Gas”. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal Of Environmental And Occupational Health Policy, 27(1), 68-91. Web.

Wenzel, C. (2012). A case study – Hydraulic fracturing geography: The case of the Eagle Ford Shale, TX, USA. Texas State University-San Marcos, San Marcos, Texas.

White E, Fell, M., and Smith L (2015). Shale gauchos and fracking. London: House of Commons Library, Web.

Xin-gang, Z., Xin, M., Ying, Z., & Pei-ling, L. (2020). Policy inducement effect in energy efficiency: An empirical analysis of China. Energy, 211, 118726. Web.

Xiong, S., Ma, X., & Ji, J. (2019). The impact of industrial structure efficiency on provincial industrial energy efficiency in China. Journal Of Cleaner Production, 215, 952-962. Web.

Zhang, Y., Chao, Q., Zheng, Q., & Huang, L. (2017). The withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement and its impact on global climate change governance.Advances In Climate Change Research, 8(4), 213-219. Web.

Zhu, W., Zhang, Z., Li, X., Feng, W., & Li, J. (2019). Assessing the effects of technological progress on energy efficiency in the construction industry: A case of China. Journal Of Cleaner Production, 238, 117908. Web.

Zierler, R., Wehrmeyer, W., & Murphy, R. (2017). The energy efficiency behavior of individuals in large organizations: A case study of a major UK infrastructure operator. Energy Policy, 104, 38-49. Web.